5. Implications for Conservation of the Nicobar Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Village Contingency Plan

Village Contingency Plan 1 Andaman and Nicobar Administration Rescue 2012 Shelter Management Psychosocial Care NDMA SCR Early Warning Rescue First Aid Mock Drill A&N Islands Disaster Management Plan 2012 I N D E X SL. NO. CONTENTS PAGE NO. 1 Map of A&N Islands 07 CHAPTER CONTENTS PAGE NO. I Introduction 08 II Hazard Analysis 11 III Union Territory Disaster Management System 24 IV UT Disaster Management Executive Committee 32 V District Disaster Management 35 VI Directorate of Disaster Management 52 VII Incident Response System 64 VIII Village Contingency Plan 90 IX Disaster Mitigation 104 X Preparedness Plan 128 XI Response Plan 133 XII Rehabilitation 140 XIII Appraisal, Documentation and Reporting 141 XIV Standard Operating Procedures 143 XV Glossary of Terms 150 XVI Explanations 155 XVII Abbreviations 160 Directorate of Disaster Management | Andaman and Nicobar Administration 1 A&N Islands Disaster Management Plan 2012 Directorate of Disaster Management | Andaman and Nicobar Administration 2 A&N Islands Disaster Management Plan 2012 Directorate of Disaster Management | Andaman and Nicobar Administration 3 A&N Islands Disaster Management Plan 2012 Directorate of Disaster Management | Andaman and Nicobar Administration 4 A&N Islands Disaster Management Plan 2012 Directorate of Disaster Management | Andaman and Nicobar Administration 5 A&N Islands Disaster Management Plan 2012 Directorate of Disaster Management | Andaman and Nicobar Administration 6 A&N Islands Disaster Management Plan 2012 Directorate of Disaster Management | Andaman and Nicobar Administration 7 A&N Islands Disaster Management Plan 2012 Chapter-I INTRODUCTION ISLANDS AT A GLANCE 1.1 LOCATION 1.1.1 The Union Territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands stretches over 700 kms from North to South with 37 inhabited Islands. -

Recommendations on Improving Telecom Services in Andaman

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India Recommendations on Improving Telecom Services in Andaman & Nicobar Islands and Lakshadweep 22 nd July, 2014 Mahanagar Doorsanchar Bhawan Jawahar Lal Nehru Marg, New Delhi – 110002 CONTENTS CHAPTER-I: INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER- II: METHODOLOGY FOLLOWED FOR THE ASSESSMENT OF THE TELECOM INFRASTRUCTURE REQUIRED 10 CHAPTER- III: TELECOM PLAN FOR ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS 36 CHAPTER- IV: COMPREHENSIVE TELECOM PLAN FOR LAKSHADWEEP 60 CHAPTER- V: SUPPORTING POLICY INITIATIVES 74 CHAPTER- VI: SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS 84 ANNEXURE 1.1 88 ANNEXURE 1.2 90 ANNEXURE 2.1 95 ANNEXURE 2.2 98 ANNEXURE 3.1 100 ANNEXURE 3.2 101 ANNEXURE 5.1 106 ANNEXURE 5.2 110 ANNEXURE 5.3 113 ABBREVIATIONS USED 115 i CHAPTER-I: INTRODUCTION Reference from Department of Telecommunication 1.1. Over the last decade, the growth of telecom infrastructure has become closely linked with the economic development of a country, especially the development of rural and remote areas. The challenge for developing countries is to ensure that telecommunication services, and the resulting benefits of economic, social and cultural development which these services promote, are extended effectively and efficiently throughout the rural and remote areas - those areas which in the past have often been disadvantaged, with few or no telecommunication services. 1.2. The Role of telecommunication connectivity is vital for delivery of e- Governance services at the doorstep of citizens, promotion of tourism in an area, educational development in terms of tele-education, in health care in terms of telemedicine facilities. In respect of safety and security too telecommunication connectivity plays a vital role. -

TERESSA ISLAND Sl.No

TERESSA ISLAND Sl.No. Particulars 31.12.2006 1. Area (Sq Km) 101.40 2. Census Villages (2001Census) 11 (i) Inhabited 11 1 Aloorang 2 Aloora 3 Enam 4Luxi 5 Kalara 6 Chuk Machi 7 Safed Balu 8 Minyuk 9 Kanahinot 10 Kalasi 11 Bengali (ii) Uninhabitted NIL 3. Revenue Villages NIL 4. Panchayat Bodies NIL 5. House Holds (2001 Census) 415 6. Population (2001 Census) 2026 Male 1081 Female 945 7. ST Population (2001 Census) 1826 Male 944 Female 882 8. Languages Spoken Nicobari & Hindi 9. Main Religion Hinduism, Christianity & Islam 10. Occupation – Main Workers (2001 Census) (i) Cultivators 4 (ii) Household Industries 443 (iii) Other Workers 184 11. Villages provided with piped water 5 supply 12. Health Service (a) Institutions (i) Primary Health Centre 1 (ii) Sub Centre 4 (b) Health Manpower (i) Doctors 1 (ii) Nurses/Midwives/LHVs 10 (iii) Para Medical Staff 29 (c) Bed Strength 10 13. Civil Supplies (i) Fair Price Shops 1 (ii) Ration Cards 947 (iii) Quantity Of Rice (Kg) 50000 14. Education (a) Institutions (i) Primary School 7 (ii) Middle School 1 (iii) Secondary School 1 59 ISLAND-WISE STATISTICAL OUTLINE - 2006 (b) Enrolment (i) Primary School 183 (ii) Middle School 82 (iii) Secondary School 193 (c) Teaching Staff (i) Primary School 10 (ii) Middle School 7 (iii) Secondary School 9 15. Social Welfare NIL 16. Electricity (i) Villages electrified 6 (ii) Electric Connections provided 4 17. Agriculture (i) Cultivable Area NE (ii) Main Crops Coconut & Arecanut (iii) Irrigation Sources NIL 18. Veterinary Service (i) Veterinary Sub Dispensary 1 (ii) Artificial insemination centre 1 (iii) Para Veterinary Staff 2 19. -

November 17-2

Tuesday 2 Daily Telegrams November 17, 2020 GOVT. PRIMARY SCHOOL No. TN/DB/PHED/2020/1277 27 SUBHASGRAM - 2 HALDER PARA, SARDAR TIKREY DO OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE ENGINEER NSV, SUBHASHGRAM GOVT. PRIMARY SCHOOL PUBLIC HEALTH ENGINEERING DIVISION 28 SUBHASGRAM - 3 DAS PARA, DAKHAIYA PARA DO A.P.W.D., PORT BLAIR NSV, SUBHASHGRAM th SCHOOL TIKREY, SUB CENTER Prothrapur, dated the 13 November 2020. COMMUNITY HALL, 29 KHUDIRAMPUR AREA, STEEL BRIDGE, AAGA DO KHUDIRAMPUR TENDER NOTICE NALLAH, DAM AREA (F) The Executive Engineer, PHED, APWD, Prothrapur invites on behalf of President of India, online Item Rate e- BANGLADESH QUARTER, MEDICAL RAMAKRISHNAG GOVT. PRIMARY SCHOOL tenders (in form of CPWD-8) from the vehicle owners / approved and eligible contractors of APWD and Non APWD 30 COLONY AREA, SAJJAL PARA, R K DO RAM - 1 RAMKRISHNAGRAM Contractors irrespective of their enlistment subject to the condition that they have experience of having successfully GRAM HOUSE SITE completed similar nature of work in terms of cost in any of the government department in A&N Islands and they should GOVT. PRIMARY SCHOOL RAMAKRISHNAG BAIRAGI PARA, MALO PARA, 31 VV PITH, DO not have any adverse remarks for following work RAM - 2 PAHAR KANDA NIT No. Earnest RAMKRISHNAGRAM Sl. Estimated cost Time of Name of work Money RAMAKRISHNAG COMMUNITY HALL, NEAR MAGAR NALLAH WATER TANK No. put to Tender Completion 32 DO Deposit RAM - 3 VKV, RAMKRISHNAGRAM AREA, POLICE TIKREY, DAS PARA VIDYASAGARPAL GOVT. PRIMARY SCHOOL SAITAN TIKRI, PANDEY BAZAAR, 1 NIT NO- R&M of different water pump sets under 33 DO 15/DB/ PHED/ E & M Sub Division attached with EE LI VS PALLY HELIPAD AREA GOVT. -

A Recent Bat Survey Reveals Bukit Barisan Selatan Landscape As A

A Recent Bat Survey Reveals Bukit Barisan Selatan Landscape as a Chiropteran Diversity Hotspot in Sumatra Author(s): Joe Chun-Chia Huang, Elly Lestari Jazdzyk, Meyner Nusalawo, Ibnu Maryanto, Maharadatunkamsi, Sigit Wiantoro, and Tigga Kingston Source: Acta Chiropterologica, 16(2):413-449. Published By: Museum and Institute of Zoology, Polish Academy of Sciences DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3161/150811014X687369 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3161/150811014X687369 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Acta Chiropterologica, 16(2): 413–449, 2014 PL ISSN 1508-1109 © Museum and Institute of Zoology PAS doi: 10.3161/150811014X687369 A recent -

Fruit Bats Comprised of Only a Few Individuals, Also Previously Located by the Micronesian Megapode Team, Was Confirmed from the Helicopter Search of SA Col

Population Assessment of the Mariana Fruit Bat (Pteropus mariannus mariannus) on Anatahan, Sarigan, Guguan, Alamagan, Pagan, Agrihan, Asuncion, and Maug; 15 June – 10 July 2010 Administrative Report Pteropus mariannus mariannus at a roost on Pagan, Photograph by E. W. Valdez Ernest W. Valdez U. S. Geological Survey Fort Collins Science Center, Arid Lands Field Station Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001 Administrative Reports are considered to be unpublished and may not be cited or quoted except in follow-up administrative reports to the same Federal agency or unless the agency releases the report to the public. Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................ 3 METHODS AND MATERIALS ....................................................................................................................... 4 RESULTS ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 SARIGAN (15–16 June 2010) .................................................................................................................... 7 GUGUAN (17–18 June 2010) ..................................................................................................................... 7 ALAMAGAN (19–21 June 2010; 10 July 2010) -

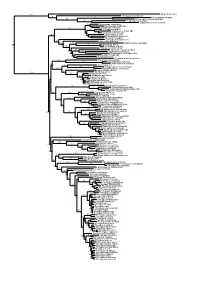

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

Chapter 2 Introduction to the Geography and Geomorphology Of

Downloaded from http://mem.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on February 7, 2017 Chapter 2 Introduction to the geography and geomorphology of the Andaman–Nicobar Islands P. C. BANDOPADHYAY1* & A. CARTER2 1Department of Geology, University of Calcutta, 35 Ballygunge Circular Road, Kolkata-700019, India 2Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences, Birkbeck, University of London, London, UK *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The geography and the geomorphology of the Andaman–Nicobar accretionary ridge (islands) is extremely varied, recording a complex interaction between tectonics, climate, eustacy and surface uplift and weathering processes. This chapter outlines the principal geographical features of this diverse group of islands. Gold Open Access: This article is published under the terms of the CC-BY 3.0 license The Andaman–Nicobar archipelago is the emergent part of a administrative headquarters of the Nicobar Group. Other long ridge which extends from the Arakan–Yoma ranges of islands of importance are Katchal, Camorta, Nancowry, Till- western Myanmar (Burma) in the north to Sumatra in the angchong, Chowra, Little Nicobar and Great Nicobar. The lat- south. To the east the archipelago is flanked by the Andaman ter is the largest covering 1045 km2. Indira Point on the south Sea and to the west by the Bay of Bengal (Fig. 1.1). A coast of Great Nicobar Island, named after the honorable Prime c. 160 km wide submarine channel running parallel to the Minister Smt Indira Gandhi of India, lies 147 km from the 108 N latitude between Car Nicobar and Little Andaman northern tip of Sumatra and is India’s southernmost point. -

An Daman N I Co Bar Islands

IMPERIAL GAZETfEER OF INDIA PROVINCIAL SERIES AN DAMAN AND N I CO BAR ISLANDS • SUPERINTENDENT OF GOVERNMENT PRINTING CALCUTTA . ,. • 1909 Price Rs:·~:_s, or 2s. 3d.] PREFACE THE articles in this volume were written by Lieut.-Colonel Sir Richard C. Temple, Bart., C.I.E., formerly Chid Com- • missioner, and have been brought up to date by the present officers of the Penal Settlement at Port Blair. · As regards the Andamans, the sections on Geology, Botany, and Fauna are based on notes supplied respectively by Mr. T. H. Holland, Director of the Geological Survey of India; Lieut.-Colonel Prain, I. M.S., formerly Superintendent of the Royal Botanical Gardens, Calcutta; and Major A. R. S. Anderson, I.M.S., formerly Senior Medical Officer, Port Blair. · Am~ng the printed works chiefly used ~ay be mentioned those of Mr. E. H. Man, C.I.E., and Mr. M. V. Portman, both formerly officers of the Penal Settlement. As regards the Nicobars, the sections on Geology, Botany, and Zoology are chiefly based on the notes of Dr. Rink of the Danish Ga!athea expedition, of Dr. von lfochstetter of the Austrian Novara expedition, and of the late Dr. Valentine Ball. The other printed works chiefly 11sed are those of Mr. E. H. Man, C.I.E., and the late Mr. de Roepstorff, an officer of the Penal Settlement. In both accounts. official reports have been freely used, while the article on the Penal Settlement at Port Blair is entirely based on them. For the remarks on the languages of the native population Sir Richard Temple is responsible. -

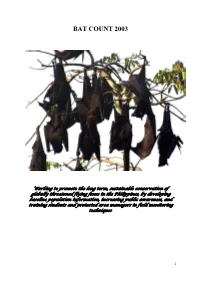

Bat Count 2003

BAT COUNT 2003 Working to promote the long term, sustainable conservation of globally threatened flying foxes in the Philippines, by developing baseline population information, increasing public awareness, and training students and protected area managers in field monitoring techniques. 1 A Terminal Report Submitted by Tammy Mildenstein1, Apolinario B. Cariño2, and Samuel Stier1 1Fish and Wildlife Biology, University of Montana, USA 2Silliman University and Mt. Talinis – Twin Lakes Federation of People’s Organizations, Diputado Extension, Sibulan, Negros Oriental, Philippines Photo by: Juan Pablo Moreiras 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Large flying foxes in insular Southeast Asia are the most threatened of the Old World fruit bats due to deforestation, unregulated hunting, and little conservation commitment from local governments. Despite the fact they are globally endangered and play essential ecological roles in forest regeneration as seed dispersers and pollinators, there have been only a few studies on these bats that provide information useful to their conservation management. Our project aims to promote the conservation of large flying foxes in the Philippines by providing protected area managers with the training and the baseline information necessary to design and implement a long-term management plan for flying foxes. We focused our efforts on the globally endangered Philippine endemics, Acerodon jubatus and Acerodon leucotis, and the bats that commonly roost with them, Pteropus hypomelanus, P. vampyrus lanensis, and P. pumilus which are thought to be declining in the Philippines. Local participation is an integral part of our project. We conducted the first national training workshop on flying fox population counts and conservation at the Subic Bay area. -

Species-Edition-Melanesian-Geo.Pdf

Nature Melanesian www.melanesiangeo.com Geo Tranquility 6 14 18 24 34 66 72 74 82 6 Herping the final frontier 42 Seahabitats and dugongs in the Lau Lagoon 10 Community-based response to protecting biodiversity in East 46 Herping the sunset islands Kwaio, Solomon Islands 50 Freshwater secrets Ocean 14 Leatherback turtle community monitoring 54 Freshwater hidden treasures 18 Monkey-faced bats and flying foxes 58 Choiseul Island: A biogeographic in the Western Solomon Islands stepping-stone for reptiles and amphibians of the Solomon Islands 22 The diversity and resilience of flying foxes to logging 64 Conservation Development 24 Feasibility studies for conserving 66 Chasing clouds Santa Cruz Ground-dove 72 Tetepare’s turtle rodeo and their 26 Network Building: Building a conservation effort network to meet local and national development aspirations in 74 Secrets of Tetepare Culture Western Province 76 Understanding plant & kastom 28 Local rangers undergo legal knowledge on Tetepare training 78 Grassroots approach to Marine 30 Propagation techniques for Tubi Management 34 Phantoms of the forest 82 Conservation in Solomon Islands: acts without actions 38 Choiseul Island: Protecting Mt Cover page The newly discovered Vangunu Maetambe to Kolombangara River Island endemic rat, Uromys vika. Image watershed credit: Velizar Simeonovski, Field Museum. wildernesssolomons.com WWW.MELANESIANGEO.COM | 3 Melanesian EDITORS NOTE Geo PRODUCTION TEAM Government Of Founder/Editor: Patrick Pikacha of the priority species listed in the Critical Ecosystem [email protected] Solomon Islands Hails Partnership Fund’s investment strategy for the East Assistant editor: Tamara Osborne Melanesian Islands. [email protected] Barana Community The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) Contributing editor: David Boseto [email protected] is designed to safeguard Earth’s most biologically rich Prepress layout: Patrick Pikacha Nature Park Initiative and threatened regions, known as biodiversity hotspots. -

Sharania Anthony

CHAPTER-I INTRODUCTION Andaman and Nicobar Islands is situated in the Bay of Bengal. The Nicobar archipelago in the Bay of Bengal as well as a part of it in the Indian Ocean is the abode of the Nicobarese a scheduled tribe of India.It is separated by the turbulent ten degree channel from the Andamans and spread over 300 kilometres.The Archipelago comprises nineteen islands namely Car Nicobar, Batti Malv, Chowra, Tillangchong, Teressa, Bompoka, Kamorta, Trinkat, Nancowry, Kachal, Meroe, Trak, Treis, Menchal, Pulo Milo, Little Nicobar, Cobra, Kondul, And Great Nicobar. These geographical names, given by the foreigners, are not used by the indigenous people of the islands. The native names of the islands as well as their dimensions are set out in descending order from north to south. Of the nineteen islands only twelve are inhabited while seven remain uninhabited. The inhabitants of these twelve, Teressa, Bompoka, Nancowry, Kamorta, Trinkat and Kachal, Great Nicobar, Little islands are divided into five groups again, depending on language differentiation among the Nicobarese living in different islands. Accordingly, the groups are located in Car Nicobar, Chowra Nicobar, Pulo Milo and Kondul Islands. Broadly the Nicobars can be divided into three groups: 1. Car Nicobar: The Island of Car Nicobar popularly known as Carnic, the headquarters of the Nicobar Islands, is a flat piece of land with an area of 24 sq.kms. It has an airfield which receives a Boeing 737 every Monday from Calcutta, via, Port Blair. In fact, this is the only airlink with the rest of the world. 2.