Lethal Kinship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan Paniscus)

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Editors: Dr Jeroen Stevens Contact information: Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp – K. Astridplein 26 – B 2018 Antwerp, Belgium Email: [email protected] Name of TAG: Great Ape TAG TAG Chair: Dr. María Teresa Abelló Poveda – Barcelona Zoo [email protected] Edition: First edition - 2020 1 2 EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (February 2020) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA APE TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. -

Recent Developments in the Study of Wild Chimpanzee Behavior

Evolutionary Anthropology 9 ARTICLES Recent Developments in the Study of Wild Chimpanzee Behavior JOHN C. MITANI, DAVID P. WATTS, AND MARTIN N. MULLER Chimpanzees have always been of special interest to anthropologists. As our organization, genetics and behavior, closest living relatives,1–3 they provide the standard against which to assess hunting and meat-eating, inter-group human uniqueness and information regarding the changes that must have oc- relationships, and behavioral endocri- curred during the course of human evolution. Given these circumstances, it is not nology. Our treatment is selective, and surprising that chimpanzees have been studied intensively in the wild. Jane Good- we explicitly avoid comment on inter- all4,5 initiated the first long-term field study of chimpanzee behavior at the Gombe population variation in behavior as it National Park, Tanzania. Her observations of tool manufacture and use, hunting, relates to the question of chimpanzee and meat-eating forever changed the way we define humans. Field research on cultures. Excellent reviews of this chimpanzee behavior by Toshisada Nishida and colleagues6 at the nearby Mahale topic, of central concern to anthropol- Mountains National Park has had an equally significant impact. It was Nishida7,8 ogists, can be found elsewhere.12–14 who first provided a comprehensive picture of the chimpanzee social system, including group structure and dispersal. SOCIAL ORGANIZATION No single issue in the study of wild Two generations of researchers erything about the behavior of these chimpanzee behavior has seen more have followed Goodall and Nishida apes in nature. But this is not the case. debate than the nature of their social into the field. -

Gorilla Beringei (Eastern Gorilla) 07/09/2016, 02:26

Gorilla beringei (Eastern Gorilla) 07/09/2016, 02:26 Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia ChordataMammaliaPrimatesHominidae Scientific Gorilla beringei Name: Species Matschie, 1903 Authority: Infra- specific See Gorilla beringei ssp. beringei Taxa See Gorilla beringei ssp. graueri Assessed: Common Name(s): English –Eastern Gorilla French –Gorille de l'Est Spanish–Gorilla Oriental TaxonomicMittermeier, R.A., Rylands, A.B. and Wilson D.E. 2013. Handbook of the Mammals of the World: Volume Source(s): 3 Primates. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. This species appeared in the 1996 Red List as a subspecies of Gorilla gorilla. Since 2001, the Eastern Taxonomic Gorilla has been considered a separate species (Gorilla beringei) with two subspecies: Grauer’s Gorilla Notes: (Gorilla beringei graueri) and the Mountain Gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei) following Groves (2001). Assessment Information [top] Red List Category & Criteria: Critically Endangered A4bcd ver 3.1 Year Published: 2016 Date Assessed: 2016-04-01 Assessor(s): Plumptre, A., Robbins, M. & Williamson, E.A. Reviewer(s): Mittermeier, R.A. & Rylands, A.B. Contributor(s): Butynski, T.M. & Gray, M. Justification: Eastern Gorillas (Gorilla beringei) live in the mountainous forests of eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, northwest Rwanda and southwest Uganda. This region was the epicentre of Africa's "world war", to which Gorillas have also fallen victim. The Mountain Gorilla subspecies (Gorilla beringei beringei), has been listed as Critically Endangered since 1996. Although a drastic reduction of the Grauer’s Gorilla subspecies (Gorilla beringei graueri), has long been suspected, quantitative evidence of the decline has been lacking (Robbins and Williamson 2008). During the past 20 years, Grauer’s Gorillas have been severely affected by human activities, most notably poaching for bushmeat associated with artisanal mining camps and for commercial trade (Plumptre et al. -

Spatial Representation of Magnitude in Gorillas and Orangutans ⇑ Regina Paxton Gazes A,B, , Rachel F.L

Cognition 168 (2017) 312–319 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Cognition journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/COGNIT Original Articles Spatial representation of magnitude in gorillas and orangutans ⇑ Regina Paxton Gazes a,b, , Rachel F.L. Diamond c,g, Jasmine M. Hope d, Damien Caillaud e,f, Tara S. Stoinski a,e, Robert R. Hampton c,g a Zoo Atlanta, Atlanta, GA, United States b Bucknell University, Lewisburg, PA, United States c Department of Psychology, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, United States d Neuroscience Graduate Program, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, United States e Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International, Atlanta, GA, United States f Department of Anthropology, University of California Davis, Davis, CA, United States g Yerkes National Primate Research Center, Atlanta, GA, United States article info abstract Article history: Humans mentally represent magnitudes spatially; we respond faster to one side of space when process- Received 1 March 2017 ing small quantities and to the other side of space when processing large quantities. We determined Revised 24 July 2017 whether spatial representation of magnitude is a fundamental feature of primate cognition by testing Accepted 25 July 2017 for such space-magnitude correspondence in gorillas and orangutans. Subjects picked the larger quantity in a pair of dot arrays in one condition, and the smaller in another. Response latencies to the left and right sides of the screen were compared across the magnitude range. Apes showed evidence of spatial repre- Keywords: sentation of magnitude. While all subjects did not adopt the same orientation, apes showed consistent Space tendencies for spatial representations within individuals and systematically reversed these orientations SNARC Ape in response to reversal of the task instruction. -

Surrogate Motherhood

Surrogate Motherhood Page ii MEDICAL ETHICS SERIES David H. Smith and Robert M. Veatch, Editors Page iii Surrogate Motherhood Politics and Privacy Edited by Larry Gostin Indiana University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis Page iv This book is based on a special issue of Law, Medicine & Health Care (16:1–2, spring/summer, 1988), a journal of the American Society of Law & Medicine. Many of the essays have been revised, updated, or corrected, and five appendices have been added. ASLM coordinator of book production was Merrill Kaitz. © 1988, 1990 American Society of Law & Medicine All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses' Resolution on Permission constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. Manufactured in the United States of America ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48–1984. Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data Surrogate motherhood : politics and privacy / edited by Larry Gostin. p. cm. — (Medical ethics series) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0253326044 (alk. paper) 1. Surrogate mothers—Legal status, laws, etc.—United States. 2. Surrogate mothers—Civil rights—United States. 3. Surrogate mothers—United States. I. Gostin, Larry O. (Larry Ogalthorpe) II. Series. KF540.A75S87 1990 346.7301'7—dc20 [347.30617] 8945474 CIP 1 2 3 4 5 94 93 92 91 90 Page v Contents Introduction ix Larry Gostin CIVIL LIBERTIES A Civil Liberties Analysis of Surrogacy Arrangements 3 Larry Gostin Procreative Liberty and the State's Burden of Proof in Regulating Noncoital 24 Reproduction John A. -

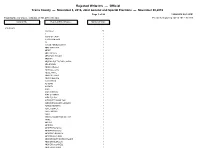

Rejected Write-Ins

Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 1 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT <no name> 58 A 2 A BAG OF CRAP 1 A GIANT METEOR 1 AA 1 AARON ABRIEL MORRIS 1 ABBY MANICCIA 1 ABDEF 1 ABE LINCOLN 3 ABRAHAM LINCOLN 3 ABSTAIN 3 ABSTAIN DUE TO BAD CANDIA 1 ADA BROWN 1 ADAM CAROLLA 2 ADAM LEE CATE 1 ADELE WHITE 1 ADOLPH HITLER 2 ADRIAN BELTRE 1 AJANI WHITE 1 AL GORE 1 AL SMITH 1 ALAN 1 ALAN CARSON 1 ALEX OLIVARES 1 ALEX PULIDO 1 ALEXANDER HAMILTON 1 ALEXANDRA BLAKE GILMOUR 1 ALFRED NEWMAN 1 ALICE COOPER 1 ALICE IWINSKI 1 ALIEN 1 AMERICA DESERVES BETTER 1 AMINE 1 AMY IVY 1 ANDREW 1 ANDREW BASAIGO 1 ANDREW BASIAGO 1 ANDREW D BASIAGO 1 ANDREW JACKSON 1 ANDREW MARTIN ERIK BROOKS 1 ANDREW MCMULLIN 1 ANDREW OCONNELL 1 ANDREW W HAMPF 1 Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 2 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT Continued.. ANN WU 1 ANNA 1 ANNEMARIE 1 ANONOMOUS 1 ANONYMAS 1 ANONYMOS 1 ANONYMOUS 1 ANTHONY AMATO 1 ANTONIO FIERROS 1 ANYONE ELSE 7 ARI SHAFFIR 1 ARNOLD WEISS 1 ASHLEY MCNEILL 2 ASIKILIZAYE 1 AUSTIN PETERSEN 1 AUSTIN PETERSON 1 AZIZI WESTMILLER 1 B SANDERS 2 BABA BOOEY 1 BARACK OBAMA 5 BARAK -

Himpanzee C Chronicle

An Exclusive Publication Produced By Chimp Haven, Inc. VOLUME IX ISSUE 2 SUMMER 2009 HIMPANZEE www.chimphaven.org C CHRONICLE INSIDE THIS ISSUE: PET CHIMPANZEES HAVE BEEN IN THE NEWS THIS YEAR. Travis, who attacked a woman in Connecticut, was shot to death. Timmie was shot in Missouri when he escaped and attacked a deputy. There are countless more pet chimpanzees living in private homes throughout the United States. This edition of the Chimpanzee Chronicle discusses this serious issue. Please share it with others. WHY CHIMPANZEES DON’T MAKE GOOD PETS By Linda Brent, PhD, President and Director When chimpanzees become pets, the outcome for them or their human “family” is rarely a good one. Chimpanzees are large, wild animals who are highly intelligent and require a great deal of socialization with their mother and other chimpanzees. Sanctuaries most often hear about pet chimpanzees when they reach adolescence and are too difficult to manage any longer. Often, they bite someone or break household items. Sometimes they get loose or seriously attack a person. Generally speaking, these actions are part of normal chimpanzee behavior. An adolescent male chimpanzee begins to try to dominate others as he works his way up the dominance hierarchy or social ladder. He does this by BOARD OF displaying, hitting and throwing objects, and sometimes attacking others. Pet chimpanzees do not have the benefit of a normal social group as an outlet for their behavior, and often these DIRECTORS behaviors are directed at human caregivers or strangers. Since chimpanzees can easily weigh as much as a person—but are far stronger—they are obviously dangerous animals to have in the Thomas Butler, D.V.M., M.S. -

Calamity for Wild Orangutans in Borneo

et21/1 oge Sees—e eaica ouce as ao a ami- isao wo ee o ou e Aima Weae Isiue a see as is easue o yeas—waks wi e Seeses og May See ou aecia- io o M Sees o age 13 May ese was a ieesig caace; se was aoe y e Seeses ae a aumaic eay ie as a say o og Isa Se ie i 199 vr pht b ln Mr rtr Maoie Cooke ai i eick uciso eeo G ewe Cisie Sees Cyia Wiso Oices Cisie Sees esie Cyia Wiso ice esie eeo G ewe Seceay eick uciso easue Sntf Ctt Maoie Ace Gea ea ee ey M aaa Oas "Tamworth Two" Win Fame by Cheating the Butcher oge aye The two pigs shown above, ickame uc Cassiy a Suace ig Samue eacock M o Was M wee e suec owiesea uic symay i auay we ey escae om a Mamesuy Ega aaoi soy eoe ey wee o e saug- Intrntnl Ctt ee Aie e Au a M - Meico We ey saw ei oe kie e ime gige-cooe igs eue G Aikas M - Geece saugeouse wokes wo case em o e miues i uc wigge Amassao aaak usai - agaes oug a oe i e wa a Suace oowe ey e swam acoss e Agea Kig - Uie Kigom ie Ao o a sma woo ey se si ays o e u uig wic ey Simo Muciu - Keya cause quie a o o meia a uic aeio as we as comica eos o Gooeo Sui - Cie aee em Ms umiiko ogo - aa Kaus esegaa - emak ey wee eeuay caug uc (acuay a emae was coee i a AeeyYaoko - ussia ie wie Suace was aquiie y e SCA I ig o e ooiey e ocie escaees a wo ei owe cage is mi aou aig Stffnd Cnltnt em saugee a ey wi ie ou ei ies i a aima sacuay eay Comue Cosua o Geie Assisa o e Oices iae aeso am Aima Cosua ...But Slaughterhouse Conditions Are No LaughingMatter ye uciso Wae Camaig Cooiao oug e amwo wos sow a a ay eig saugeouse Cay iss Eecuie ieco coiios ae ayig u -

Supreme Court of the State of New York County of New York ______

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF NEW YORK __________________________________________________ In the Matter of a Proceeding under Article 70 of the CPLR for a Writ of Habeas Corpus, THE NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., on behalf of KIKO, MEMORANDUM OF Petitioner, LAW IN SUPPORT OF -against- PETITION FOR HABEAS CORPUS CARMEN PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., CHRISTIE E. Index No. PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., and THE PRIMATE SANCTUARY, INC., Respondents. __________________________________________________ Elizabeth Stein, Esq. Attorney for Petitioner 5 Dunhill Road New Hyde Park, NY 11040 Phone (516) 747-4726 Steven M. Wise, Esq. Attorney for Petitioner 5195 NW 112th Terrace Coral Springs, FL 33076 Phone (954) 648-9864 Elizabeth Stein, Esq. Steven M. Wise, Esq. Subject to pro hac vice admission January_____, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................................................................................ v I. SUMMARY OF NEW GROUNDS AND FACTS NEITHER PRESENTED NOR DETERMINED IN NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., EX REL. KIKO v. PRESTI OR NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC. ON BEHALF OF TOMMY v. LAVERY. ............................................................................................................. 1 II. INTRODUCTION AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY .................................................... 6 III. STATEMENT OF FACTS ........................................................................................... -

The Ledger and Times, April 16, 1953

Murray State's Digital Commons The Ledger & Times Newspapers 4-16-1953 The Ledger and Times, April 16, 1953 The Ledger and Times Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt Recommended Citation The Ledger and Times, "The Ledger and Times, April 16, 1953" (1953). The Ledger & Times. 1272. https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt/1272 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Murray State's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Ledger & Times by an authorized administrator of Murray State's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. :g hi A .0.• ..•••••• Aks AWL It. 11,f5N Selected As Best All sound Kentucky Community Newspaper for 1947 We Weather Are KN^ETUCKV: Fair with -ir -- terrepersteoires-neetr -Or a little Helping To 1411NNsorst• below freezing tomeht. low 30 to 34 in the east and a Build Murray , • `1,:*"\ ‘7441"--"7- 32 to 38 in the east portion. Friday fair and continued Each Day cool. r• YOUR PROGRESSIVE HOME NEWSPAPER United Press IN ITS 74th YEAR Murray, Ky., Thursday Afternioon, April 16, 1953 MURRAY POPULATION . - - 8,000 Vol. XXIX; No. 91 Vitality Dress Shoes IKE CHALLENGES RE!)s IN PEACE MOVE Basque, Red Calf and , als; In Flight Blue Calf Soon de Hoard I Now.4)':,t7".. Lions Will Be Six Point Program Listed $10.95 By LEIO, PANMUNJOM, ,./iApril 16 Sold To Aid By President To End War Al'OUttd • / (UP)-Red trucks b. /ambulances today delivered the first of 805 By MERRIMAN SMITH ,hopes with mere words and prom- I Allied sick and wounded prisoners Health Center WASHINGTON April 16 iUPI- ises and gestures," he said. -

Orangutan Positional Behavior and the Nature of Arboreal Locomotion in Hominoidea Susannah K.S

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 000:000–000 (2006) Orangutan Positional Behavior and the Nature of Arboreal Locomotion in Hominoidea Susannah K.S. Thorpe1* and Robin H. Crompton2 1School of Biosciences, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK 2Department of Human Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 3GE, UK KEY WORDS Pongo pygmaeus; posture; orthograde clamber; forelimb suspend ABSTRACT The Asian apes, more than any other, are and orthograde compressive locomotor modes are ob- restricted to an arboreal habitat. They are consequently an served more frequently. Given the complexity of orangu- important model in the interpretation of the morphological tan positional behavior demonstrated by this study, it is commonalities of the apes, which are locomotor features likely that differences in positional behavior between associated with arboreal living. This paper presents a de- studies reflect differences in the interplay between the tailed analysis of orangutan positional behavior for all age- complex array of variables, which were shown to influence sex categories and during a complete range of behavioral orangutan positional behavior (Thorpe and Crompton [2005] contexts, following standardized positional mode descrip- Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 127:58–78). With the exception tions proposed by Hunt et al. ([1996] Primates 37:363–387). of pronograde suspensory posture and locomotion, orang- This paper shows that orangutan positional behavior is utan positional behavior is similar to that of the African highly complex, representing a diverse spectrum of posi- apes, and in particular, lowland gorillas. This study sug- tional modes. Overall, all orthograde and pronograde sus- gests that it is orthogrady in general, rather than fore- pensory postures are exhibited less frequently in the pres- limb suspend specifically, that characterizes the posi- ent study than previously reported. -

Western Lowland Gorilla (Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla) Diet and Activity Budgets: Effects of Group Size, Age Class and Food Availability in the Dzanga-Ndoki

Western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) diet and activity budgets: effects of group size, age class and food availability in the Dzanga-Ndoki National Park, Central African Republic Terence Fuh MSc Primate Conservation Dissertation 2013 Dissertation Course Name: P20107 Title: Western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) diet and activity budgets: effects of group size, age class and food availability in the Dzanga-Ndoki National Park, Central African Republic Student Number: 12085718 Surname: Fuh Neba Other Names: Terence Course for which acceptable: MSc Primate Conservation Date of Submission: 13th September 2013 This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the regulations for an MSc degree. Oxford Brookes University ii Statement of originality Except for those parts in which it is explicitly stated to the contrary, this project is my own work. It has not been submitted for any degree at this or any other academic or professional institution. ……………………………………………. ………………… Signature Date Regulations Governing the Deposit and Use of Oxford Brookes University Projects/ Dissertations 1. The “top” copies of projects/dissertations submitted in fulfilment of programme requirements shall normally be kept by the School. 2. The author shall sign a declaration agreeing that the project/ dissertation be available for reading and photocopying at the discretion of the Head of School in accordance with 3 and 4 below. 3. The Head of School shall safeguard the interests of the author by requiring persons who consult the project/dissertation to sign a declaration acknowledging the author’s copyright. 4. Permission for any one other then the author to reproduce or photocopy any part of the dissertation must be obtained from the Head of School who will give his/her permission for such reproduction on to an extent which he/she considers to be fair and reasonable.