The Promise and Ambition of John Gadsby Chapman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John C. Calhoun and State Interposition in South Carolina, 1816-1833

Nullification, A Constitutional History, 1776-1833 Volume Three In Defense of the Republic: John C. Calhoun and State Interposition in South Carolina, 1816-1833 By Prof. W. Kirk Wood Alabama State University Contents Dedication Preface Acknowledgments Introduction In Defense of the Republic: John C. Calhoun and State Interposition in South Carolina, 1776-1833 Chap. One The Union of the States, 1800-1861 Chap. Two No Great Reaction: Republicanism, the South, and the New American System, 1816-1828 Chap. Three The Republic Preserved: Nullification in South Carolina, 1828-1833 Chap. Four Republicanism: The Central Theme of Southern History Chap. Five Myths of Old and Some New Ones Too: Anti-Nullifiers and Other Intentions Epilogue What Happened to Nullification and Republicanism: Myth-Making and Other Original Intentions, 1833- 1893 Appendix A. Nature’s God, Natural Rights, and the Compact of Government Revisited Appendix B. Quotes: Myth-Making and Original Intentions Appendix C. Nullification Historiography Appendix D. Abel Parker Upshur and the Constitution Appendix E. Joseph Story and the Constitution Appendix F. Dr. Wood, Book Reviews in the Montgomery Advertiser Appendix G. “The Permanence of the Union,” from William Rawle, A View of the Constitution of the United States (permission by the Constitution Society) Appendix H. Sovereignty, 1776-1861, Still Indivisible: States’ Rights Versus State Sovereignty Dedicated to the University and the people of South Carolina who may better understand and appreciate the history of the Palmetto State from the Revolution to the Civil War Preface Why was there a third Nullification in America (after the first one in Virginia in the 1790’s and a second one in New England from 1808 to 1815) and why did it originate in South Carolina? Answers to these questions, focusing as they have on slavery and race and Southern sectionalism alone, have made Southerners and South Carolinians feel uncomfortable with this aspect of their past. -

“What Are Marines For?” the United States Marine Corps

“WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Major Subject: History “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era Copyright 2011 Michael Edward Krivdo “WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Joseph G. Dawson, III Committee Members, R. J. Q. Adams James C. Bradford Peter J. Hugill David Vaught Head of Department, Walter L. Buenger May 2011 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. (May 2011) Michael E. Krivdo, B.A., Texas A&M University; M.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Joseph G. Dawson, III This dissertation provides analysis on several areas of study related to the history of the United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. One element scrutinizes the efforts of Commandant Archibald Henderson to transform the Corps into a more nimble and professional organization. Henderson's initiatives are placed within the framework of the several fundamental changes that the U.S. Navy was undergoing as it worked to experiment with, acquire, and incorporate new naval technologies into its own operational concept. -

Unlocking Eastlake Unlocking Eastlake

ng E nlocki astlak U e CREATED BY THE YOUNG EXPLAINERS OF PLYMOUTH CITY MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY No. 1. ] SEPTEMBER 22 - DECEMBER 15, 2012. [ One Penny. A STROKE OF GENIUS. UNLOCKING EASTLAKE UNLOCKING EASTLAKE It may be because of his reserved nature that Staff at the City Museum and Art Gallery are organising a range of events connected to the Eastlake is not remembered as much as he exhibition, including lunchtime talks and family-friendly holiday workshops. INTRODUCING deserves to be. Apart from securing more Visit www.plymouth.gov.uk/museumeastlake to stay up to date with what’s on offer! than 150 paintings for the nation, Eastlake was a key figure in helping the public gain like to i uld ntro a better understanding of the history of wo d uc WALKING TRAILS e e EASTLAKE western art. Through detailed catalogues, W THE simpler ways of picture display, and the Thursday 20th September 2012: : BRITISH ART’S PUBLIC SERVANT introduction of labels enabling free access to Grand Art History Freshers Tour information, Eastlake gave the us public art. YOUNG EXPLAINERS A chance for Art History Freshers to make friends as well as see what lmost 150 years after his Article: Laura Hughes the Museum and the Young Explainers death, the name of Sir Charles Children’s Actities / Map: Joanne Lees have to offer. The tour will focus on UNLOCKING EASTLAKE’S PLYMOUTH Eastlake has failed to live up to Editor: Charlotte Slater Eastlake, Napoleon and Plymouth. the celebrity of his legacy. Designer: Sarah Stagg A Illustrator (front): Alex Hancock Saturday 3rd November 2012: Even in his hometown of Plymouth, blank faces During Eastlake’s lifetime his home city Illustrator (inside): Abi Hodgson Lorente Eastlake’s Plymouth: usually meet the question: “Who is Sir Charles of Plymouth dramatically altered as it A Family Adventure Through Time Eastlake?” Yet this cultural heavyweight was transformed itself from an ancient dockland Alice Knight Starting at the Museum with interactive acknowledged to be one of the ablest men of to a modern 19th century metropolis. -

Seth Eastman, a Portfolio of North American Indians Desperately Needed for Repairs

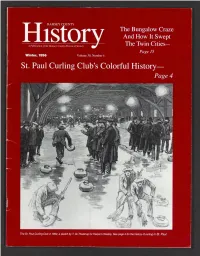

RAMSEY COUNTY The Bungalow Craze And How It Swept A Publication of the Ramsey County Historical Society The Twin Cities— Page 15 Winter, 1996 Volume 30, Number 4 St. Paul Curling Club’s Colorful History The St. Paul Curling Club in 1892, a sketch by T. de Thulstrup for Harper’s Weekly. See page 4 for the history of curling in S t Paul. RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY Executive Director Priscilla Famham Editor Virginia Brainard Kunz WARREN SCHABER 1 9 3 3 - 1 9 9 5 RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY The Ramsey County Historical Society lost a BOARD OF DIRECTORS good friend when Ramsey County Commis Joanne A. Englund sioner Warren Schaber died last October Chairman of the Board at the age of sixty-two. John M. Lindley CONTENTS The Society came President to know him well Laurie Zehner 3 Letters during the twenty First Vice President years he served on Judge Margaret M. Mairinan the Board of Ramsey Second Vice President 4 Bonspiels, Skips, Rinks, Brooms, and Heavy Ice County Commission Richard A. Wilhoit St. Paul Curling Club and Its Century-old History Secretary ers. We were warmed by his steady support James Russell Jane McClure Treasurer of the Society and its work. Arthur Baumeister, Jr., Alexandra Bjorklund, 15 The Bungalows of the Twin Cities, With a Look Mary Bigelow McMillan, Andrew Boss, A thoughtful Warren We remember the Thomas Boyd, Mark Eisenschenk, Howard At the Craze that Created Them in St. Paul Schaber at his first County big things: the long Guthmann, John Harens, Marshall Hatfield, Board meeting, January 6, series of badly- Liz Johnson, George Mairs, III, Mary Bigelow Brian McMahon 1975. -

1833-1834 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design Art, Art History and Design, School of 2011 Stealing Horses and Hostile Conflict: 1833-1834 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida Kimberly Minor University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artstudents Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the Art and Design Commons Minor, Kimberly, "Stealing Horses and Hostile Conflict: 1833-1834 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida" (2011). Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artstudents/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art, Art History and Design, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Stealing Horses and Hostile Conflict: 1833-34 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida By Kimberly Minor Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Art History Under the Supervision of Professor Wendy Katz Lincoln, Nebraska April 2011 Stealing Horses and Hostile Conflict: 1833-34 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida Kimberly Minor, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2011 Advisor: Wendy Katz The first documented Native American art on paper includes the following drawings at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska: In the Winter, 1833-1834 (two versions) by Sih-Chida (Yellow Feather) and Mato-Tope Battling a Cheyenne Chief with a Hatchet (1834) by Mato-Tope (Four Bears) as well as an untitled drawing not previously attributed to the latter. -

Eastlake's Scholarly and Artistic Achievements Wednesday 10

Eastlake's Scholarly and Artistic Achievements Wednesday 10 October 2012 Lizzie Hill & Laura Hughes Overview I will begin this Art Bite with a quotation from A Century of British Painters by Samuel and Richard Redgrave, who refer to Eastlake as one of "a few exceptional painters who have served the art they love better by their lives than their brush" . This observation is in keeping with the norm of contemporary views in which Eastlake is first and foremost seen as an art historian and collector. However, as a man who began his career as a painter, it seems it would be interesting to explore both of these aspects of his life. Therefore, this Art Bite will be examining the validity of this critique by evaluating Eastlake's artistic outputs and scholarly achievements, and putting these two aspects of his life in direct relation to each other. By doing this, the aim behind this Art Bite is to uncover the fundamental reason behind Eastlake's contemporary and historical reputation, and ultimately to answer; - What proved to be Eastlake's best weapon in entering the Art Historical canon: his brain or his brush? Introduction So, who was Sir Charles Lock Eastlake? To properly be able to compare his reputation as an art historian versus being a painter himself, we need to know the basic facts about the man. A very brief overview is that Eastlake was born in Plymouth in 1793 and from an early age was determined to be a painter. He was the first student of the notable artist Benjamin Haydon in January 1809 and received tuition from the Royal Academy schools from late 1809. -

Examine the Exquisite Portraits of the American Indian Leaders Mckenney

Examine the exquisite portraits of the American Indian leaders McKenney, Thomas, and James Hall, History of the Indian Tribes of North America. Philadelphia: Edward C. Biddle (parts 1-5), Frederick W. Greenough (parts 6-13), J.T. Bowen (part 14), Daniel Rice and James G. Clark (parts 15-20), [1833-] 1837-1844 20 Original parts, folio (21.125 x 15.25in.: 537 x 389 mm.). 117 handcolored lithographed portraits after C. B. King, 3 handcolored lithographed scenic frontispieces after Rindisbacher, leaf of lithographed maps and table, 17 pages of facsimile signatures of subscribers, leaf of statements of the genuiness of the portrait of Pocahontas, part eight with the printed notice of the correction of the description of the War Dance and the cancel leaf of that description (the incorrect cancel and leaf in part 1), part 10 with erratum slip, part 20 with printed notice to binders and subscribers, title pages in part 1 (volume 1, Biddle imprint 1837), 9 (Greenough imprint, 1838), 16 (volume 2, Rice and Clark imprint, 1842), and 20 (volume 3, Rice and Clark imprint, 1844); some variously severe but, usually light offsetting and foxing, final three parts with marginal wormholes, not affecting text or images. Original printed buff wrappers; part 2 with spine lost and rear wrapper detached, a few others with spines shipped, part 11 with sewing broken and text and plates loose, part 17 with large internal loss of front wrapper affecting part number, some others with marginal tears or fraying, some foxed or soiled. Half maroon morocco folding-case, gilt rubbed. FIRST EDITION, second issue of title-page of volume 1. -

University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating' adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Indiana Magazine of History the Author Has Used Swedish Sources

156 Indiana Magazine of History The author has used Swedish sources extensively and appears to have a detailed grasp of his materials. However, the book suffers from a maddening confusion in chronology. Elmen often fails to date his accounts of events and further confuses the reader by inserting dated references to earlier and later events in order to amplify the obscure “present” of his narrative (e.g., chapter two). The bibliography is ex- tensive and the index reliable. Indiana Historical Society, Lana Ruegamer Tam Indianapolis The Indian Legacy of Charles Bird King. By Herman J. Viola. (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press and Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1976. Pp. 152. Illustra- tions, notes, bibliography, index. $19.95.) Rhode Island born Charles Bird King studied under Benjamin West in England before settling in the District of Columbia after the War of 1812. A successful portrait paint- er, King met Thomas McKenney, superintendent of Indian trade and later head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Mc- Kenney had already begun “The Archives of the American Indian,” a collection of Indian artifacts, and decided to em- ploy King to add portraits to his archives. In 1822 McKenney commissioned King to portray Pawnee, Oto, Omaha, and other delegates who were in Washington at government request. In the next twenty years King did portraits of at least 143 Indian leaders who visited the capital and often did replicas for himself and for his subjects. Included were such notable figures Petalesharro of the Pawnees, Keokuk and Black Hawk of the Sac and Fox, and Red Jacket of the Senecas. -

Národní Galerie V Čr a Uk

Masarykova univerzita Ekonomicko-správní fakulta Studijní obor: Veřejná ekonomika INSTITUCIONÁLNÍ KOMPARACE KONTINENTÁLNÍHO A ANGLOAMERICKÉHO MODELU: NÁRODNÍ GALERIE V ČR A UK Institutional comparison of a continental and an Anglo- american models: National Gallery in UK and CZ Diplomová práce Vedoucí diplomové práce: Autor: Ing. František Svoboda, Ph.D. Bc. Veronika Králíková Kyjov, 2009 Jméno a příjmení autora: Veronika Králíková Název diplomové práce: Institucionální komparace kontinentálního a angloamerického modelu: Národní Galerie ČR a UK Název v angličtině: Institutional comparison of a continental and an Anglo- american models: National Gallery in UK and CZ Katedra: Veřejná ekonomika Vedoucí diplomové práce: Ing. František Svoboda, Ph.D. Rok obhajoby: 2009 Anotace Předmětem diplomové práce „Institucionální komparace kontinentálního a angloamerického modelu: Národní Galerie ČR a UK“ je analýza historického vývoje těchto institucí a jejich vzájemná komparace. První část popisuje historický vývoj a tedy i východiska, na kterých byly obě galerie vybudovány. Druhá část je věnována dnešní podobě galerií. Závěrečná kapitola je zaměřena na jejich vzájemnou komparaci. Annotation The objective of the thesis „Institutional comparison of a continental and an Anglo-american models: National Gallery in UK and CZ“ is historical development analysis and their mutual comparison. The first part describes the historical making and thus also origins of the establishment of both galleries. The second part presents their contemporary form. The closing -

Young Portrait Explorers: Sequoyah

Young Portrait Explorers: Sequoyah Learning Objective: Learn about Sequoyah (c. 1770 – 1843), creator of the Cherokee syllabary (symbols used like an alphabet), and practice your writing skills. Portrait Discussion: Look at the portrait of Sequoyah. Spend 30 seconds letting your eyes wander from the top of the painting to the bottom. Objects: Notice the objects in this portrait. Can you spot the following: a feather pen, an inkwell (small jar used to hold ink for writing), a pipe, a medal, and something with writing on it? What clues might these objects provide about Sequoyah’s life? Can you read it the writing Sequoyah presents? Some of the symbols might look familiar, but not all. This is the Cherokee syllabary – the symbols Sequoyah created to form a written version of the Cherokee language. Each symbol represents a sound or syllable. Just like the letters in an alphabet, the symbols can be combined to form words. The Cherokee Nation (a North American Indian people or community) has a rich tradition of storytelling but did not use a written language until the 1800s, when Sequoyah introduced his syllabary. Soon after, Cherokee history, traditions, and laws were put down in writing. Pose: Do you think Sequoyah is sitting or standing? Can you try posing like he does? Pay attention to what he is doing with his hands – they help us to understand his story. With one hand, he holds the syllabary. With the other hand, he points at it. We might expect Sequoyah to be reading, but notice how his eyes look out from the painting. -

The Turner Collector: Elhanan Bicknell

The Turner Collector: Elhanan Bicknell PETER BICKNELL Cambridge with HELEN GUITERMAN London `There took place last Saturday an event in London such as, we serge business; this had been moved to London from Taunton earlier venture to think, could scarcely in the same time and under the same in the century. William was musical, a mathematician, something of a conditions have happened in any other city in the world. It was not a writer and a great reader. He found the wool trade uncongenial and the great national event - a Royal reception, or a popular demonstration. It year after Elhanan's birth sold the business to buy the freehold of an was not anything attaching to or symbolising institutions or sentiments 'Academy' attended by some i 00 scholars, in the old palace of the peculiarly British. It had nothing to do with our glorious constitution, Bishop of Lincoln at Ponder's End, Enfield. The school prospered, our lords, our commons, our free press, our meteor-flag, our climate, and in December 1804 he moved it and his residence to Surrey our racehorses, or our bitter beer . It was merely a sale of Hall, Lower Tooting. Elhanan's curious name' came through the pictures. The collection of paintings thus sold had been gathered Bicknell connection with the Free Churches, John Wesley having been together by a private Englishman, a man of comparatively obscure a friend of the family at Taunton and in London; William's closest position, a man engaged at one time in mere trade - a man not even friend was the American preacher, the Reverend Elhanan pretending to resemble a Genoese or Florentine merchant prince, but Winchester, author of Universal Restoration, a book which gave simply and absolutely a Londoner of the middle class actively William great comfort and satisfaction.