NR2202 05 Crockford 93..114

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New World Tragedy $13.95

... - Joumey to Nowhere A NEW WORLD TRAGEDY $13.95 Rarely does a book come along which so transcends its apparent subject that the reader is ultimately given something larger, richer, and more revealing than he might initially have imagined. Already published in Eng land to overwhelming acclaim (see back of jacket), Shiva Naipaul’s Journey to Nowhere is such a book — a “power ful, lucid, and beautifully written book” (The Spectator) that is destined to be one of the most controversial works of 1981. In it, this major writer takes us far beyond the events and surface details surrounding the tragedy of Jones town and the People’s Temple —and gives us his remark able, unique perspective on the deadly drama of ideas, environments, and unholy alliances that shaped those events both in Guyana and, even more significantly, in America. Journey to Nowhere is, on one level, a “brilliantly edgy safari” (New Statesman) inside the Third World itself—a place of increasing importance in our lives—and on another, a book about America, about the corrupt and corrupting ideologies and chi-chi politics of the past twenty years that enabled the Reverend Jim Jones and the Temple to flourish and grow powerful in California and Guyana. Drawing on interviews —with former members of the Temple, various officials, and such people as Buckmin ster Fuller, Huey Newton, Clark Kerr, and others —on documents, and most importantly, on his own strong, clear reactions to what he observed, Naipaul examines the Guyana of Forbes Bumham, the CIA stooge turned Third World socialist leader, whose stated ideals of socialism, racial brotherhood, and cooperative agricul tural enterprise coincided so neatly, we learn for the first time, with those of the People’s Temple — ideals that led all too easily to violence and death. -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

The Psychology Behind Jonestown: When Extreme Obedience and Conformity Collide Abstract 2

THE PSYCHOLOGY BEHIND JONESTOWN 1 Anna Maria College The Psychology Behind Jonestown: When Extreme Obedience and Conformity Collide Submitted by: Claudia Daniela Luiz Author’s Note: This thesis was prepared by Law and Society and Psychology student, Claudia Daniela Luiz for HON 490, Honors Senior Seminar, taught by Dr. Bidwell and written under the supervision of Dr. Pratico, Psychology Professor and Head of the Psychology Department at Anna Maria College. RUNNING HEAD: THE PSYCHOLOGY BEHIND JONESTOWN 2 Abstract Notoriously throughout our history, cults of extremist religious views have made the headlines for a number of different crimes. Simply looking at instances like the Branch Davidians in Waco, or the members of the People’s Temple of Christ from Jonestown, it’s easy to see there is no lack of evidence as to the disastrous effects of what happens when these cults reach an extreme. When one person commits an atrocious crime, we can blame that person for their actions, but who do we blame when there’s 5 or even 900 people that commit a crime because they are so seemingly brainwashed by an individual that they’ll blindly follow and do whatever that individual says? Studying cases, like that of Jonestown and the People’s Temple of Christ, where extreme conformity and obedience have led to disastrous and catastrophic results is important because in the words of George Santayana “those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it.” By studying and analyzing Jonestown and the mass suicide that occurred there, people can learn how Jim Jones was able to gain complete control of the minds of his over 900 followers and why exactly people began following him in the first. -

Die Flexible Welt Der Simpsons

BACHELORARBEIT Herr Benjamin Lehmann Die flexible Welt der Simpsons 2012 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Die flexible Welt der Simpsons Autor: Herr Benjamin Lehmann Studiengang: Film und Fernsehen Seminargruppe: FF08w2-B Erstprüfer: Professor Peter Gottschalk Zweitprüfer: Christian Maintz (M.A.) Einreichung: Mittweida, 06.01.2012 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS The flexible world of the Simpsons author: Mr. Benjamin Lehmann course of studies: Film und Fernsehen seminar group: FF08w2-B first examiner: Professor Peter Gottschalk second examiner: Christian Maintz (M.A.) submission: Mittweida, 6th January 2012 Bibliografische Angaben Lehmann, Benjamin: Die flexible Welt der Simpsons The flexible world of the Simpsons 103 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2012 Abstract Die Simpsons sorgen seit mehr als 20 Jahren für subversive Unterhaltung im Zeichentrickformat. Die Serie verbindet realistische Themen mit dem abnormen Witz von Cartoons. Diese Flexibilität ist ein bestimmendes Element in Springfield und erstreckt sich über verschiedene Bereiche der Serie. Die flexible Welt der Simpsons wird in dieser Arbeit unter Berücksichtigung der Auswirkungen auf den Wiedersehenswert der Serie untersucht. 5 Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ............................................................................................. 5 Abkürzungsverzeichnis .................................................................................... 7 1 Einleitung ................................................................................................... -

Three Ways of Understanding Government Classification of Jonestown Documents

Three Ways to Understand Government Classification of Jonestown Documents Revision of paper given at Religion, Secrecy and Security: Religious Freedom and Privacy in a Global Context An Interdisciplinary Conference at Ohio State University April 2004 Rebecca Moore In 2001 my husband, Fielding McGehee III, and I filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) lawsuit against the Department of Justice. McGehee and Moore v. U.S. Department of Justice seeks to compel the Justice Department to provide an index—as required by law—to three compact disks of materials the FBI had pulled together from documents collected in Jonestown, Guyana in 1978 and from files generated in the agency’s subsequent investigation into the assassination of U.S. Congressman Leo J. Ryan. Our interest in Jonestown is both personal and professional, and in that respect I am writing as a participant observer regarding the events of 18 November 1978. I am a participant to the extent that my two sisters and nephew died in Jonestown in the mass murders-suicides which occurred under the direction of Jim Jones and I wish to know how and why. My status as a relative makes me an insider of sorts, with access to survivors of the tragedy, and with stature with government agencies as an interested party. But I am an observer as well, given my training in religious studies and my desire to interpret the events to my academic peers within a scholarly framework. I also wish to write the history of Peoples Temple, the group begun by Jones in Indianapolis which migrated to California and then to Guyana, as accurately and completely as possible. -

Religious Sects and Cults: the Study of New Religious Movements in the United States

For the personal use of teachers. Not for sale or redistribution. © Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture, 2011 Religious Sects and Cults: The Study of New Religious Movements in the United States Young Scholars in American Religion 2009-2011 Lynn S. Neal __________________________________________________________ Institutional Setting Wake Forest in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, is a private, secular university with an undergraduate college dedicated to providing students with a liberal arts education. The student body numbers around 4500, many of whom graduated in the top ten percent of their high school class. The majority of these students are from the South (53 percent) and are affiliated with some branch of Christianity (Catholicism is the single largest denomination represented). However, in recent years, the college has been working hard to increase the racial, economic, regional, and religious diversity of the undergraduate population. Eliminating the SAT requirement and admitting students based on a more holistic approach has yielded some success in this regard. Students tend to be motivated and bright, involved and inquisitive. The challenge, for many, is balancing their academic interests and expectations with their various extracurricular commitments. Wake Forest upholds the teacher-scholar ideal for its professors, which demands excellence in both teaching and research. This encourages professors to develop their pedagogical skills, to consider connections between their teaching and research, and allows for smaller classroom sizes. The faculty/student ratio on campus is 11:1. My appointment is in the Religion Department where courses serve two primary purposes. First, our introductory courses fulfill a humanities requirement for the college. -

Section I - Overview

EDUCATOR GUIDE Story Theme: History Retold Subject: The People’s Temple Discipline: Theatre SECTION I - OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................2 SECTION II – CONTENT/CONTEXT ..................................................................................................3 SECTION III - RESOURCES ..................................................................................................................6 SECTION IV – VOCABULARY .........................................................................................................10 SECTION V – PEOPLES TEMPLE HISTORICAL TIMELINE .......................................................... 13 SECTION VI – ENGAGING WITH SPARK ....................................................................................143 SECTION VII – RELATED STANDARDS.......................................................................................... 19 Actors in The People’s Temple production at Berkeley Repertory Theatre work on the play in its early stages. Still image from SPARK story, 2005. SECTION I - OVERVIEW EPISODE THEME History Retold INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES Group oral discussion, review and analysis, SUBJECT including peer review and aesthetic valuing People’s Temple Project Teacher-guided instruction, including demonstration and guidance GRADE RANGES Hands-on individual projects in which students K–12 & Post-Secondary work independently Hands-on group projects in which students assist CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS -

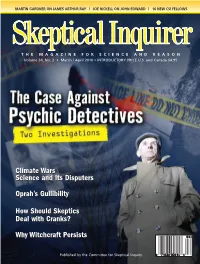

Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah's Gullibility How

SI M/A 2010 Cover V1:SI JF 10 V1 1/22/10 12:59 PM Page 1 MARTIN GARDNER ON JAMES ARTHUR RAY | JOE NICKELL ON JOHN EDWARD | 16 NEW CSI FELLOWS THE MAG A ZINE FOR SCI ENCE AND REA SON Vol ume 34, No. 2 • March / April 2010 • INTRODUCTORY PRICE U.S. and Canada $4.95 Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah’s Gullibility How Should Skeptics Deal with Cranks? Why Witchcraft Persists SI March April 2010 pgs_SI J A 2009 1/22/10 4:19 PM Page 2 Formerly the Committee For the SCientiFiC inveStigation oF ClaimS oF the Paranormal (CSiCoP) at the Cen ter For in quiry/tranSnational A Paul Kurtz, Founder and Chairman Emeritus Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Schroeder, Chairman Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow James E. Al cock, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to David J. Helfand, professor of astronomy, John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. Mar cia An gell, M.D., former ed i tor-in-chief, New Columbia Univ. Stev en Pink er, cog ni tive sci en tist, Harvard Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine Doug las R. Hof stad ter, pro fes sor of hu man un der - Mas si mo Pol id oro, sci ence writer, au thor, Steph en Bar rett, M.D., psy chi a trist, au thor, stand ing and cog ni tive sci ence, In di ana Univ. -

The Simpsons Tapped out - Analysis and Proposed Events Overview

The Simpsons Tapped Out - Analysis and Proposed Events Overview Players like myself have faithfully enjoyed The Simpsons Tapped Out (TSTO) for several years. The developers have continued to expand the game and provide updates in response to player feedback. This has been evident in tools such as the IRS Building tap radius, the Introduction Unemployment Office Job Manager and the Cut & Paste feature, all of which are greatly appreciated by players and have extended the playability of TSTO for many of us who would have otherwise found the game too tedious to continue once their Springfields grew so large. Notably, as respects Events, positive reactive efforts were identifiable in the 2017 Winter Event and the modified use of craft currency. As evident from the forums, many dedicated and heavily-invested players have grown tired with some of TSTO's stale mechanics and gameplay, as well as the proliferation of uninspired content, much of which has little to no place in Springfield, if even the world of "The Simpsons." This Premise player attitude is often displayed in the later stages of major Events as players begin to sense monotony due to a lack in changes throughout an Event, resulting in a feeling that one is merely grinding through the game to stock up on largely unwanted Items. Content-driven major Events geared toward "The Simpsons" version of Springfield with changes of pace, more like mini-Events, and the Solution addition of new Effects, enabling a variety of looks while injecting a new degree of both familiarity and customization for players. The proposed Events and gameplay changes are steeped in canonical content rather than original content. -

The Death of Representative Leo J. Ryan, People's Temple, And- Jonestown: Understanding a Tragedy

THE DEATH OF REPRESENTATIVE LEO J. RYAN, PEOPLE'S TEMPLE, AND- JONESTOWN: UNDERSTANDING A TRAGEDY HEARING 3M1 THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE, OF REPRESENTATIVES NINETY-SIXTH CONGRESS'' FIRST SESSION MAY 15, 1979 Printed for the use of the Committee on Forelgu Aftra U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 46420 WASHINGTON : 1979 H3/I1-7 COMMITTEE 014' FOREIGN AFFAIRS CLEMENT 3. ZABLOCKI, Wisconsin, Chairman 1,. I. FOUNTAIN, North Carolina WILLIAM S. BROOMFIELD, Michigan DANTE B. FASCELL, Florida EDWARD J. DERWINSKI, Illinois CHARLES C. DIGGS, JR., Michigan PAUL FINDLEY, Illinois BENJAMIN S. ROSENTHAL, New York JOHN H. BUCHANAN, JR., Alabama LEE ff. HAMILTON, Indiana LARRY WINN, Ja., Kansas LESTER L WOLFF, New York BENJAMIN A. GILMAN, New York JONATHAN B. BINGHAM, New York TENNYSON GUYSR, Ohio GUS YATRON, Pennsylvania ROBERT J. LAGOMARSINO, California CARDISS COLLINS, Illinois WILLIAM F. GOODLINO, Pennsylvania STEPHEN J. SOLARZ, New York JOEL PRITCHARD, Washington DON BONKER, Washington MILLICENT FENWICK, New Jersey GERRY R. STUDDS, Massachusetts DAN QUAYLE, Indiana ANDY IRELAND, Florida DONALD :. PEASE, Ohio DAN MICA, Florida MICHAEL D. BARNES, Maryland WILLIAM H. GRAVE II, Pennsylvania TONY P. HALL, Ohio HOWARD WOLPE, Michigan DAVID R. BOWEN, Mississippi FLOYD J. FITHIAN, Indiana JOHN J. BaDr, Jr., Ohief of Staff RoxAxxN PasuGixo, Staff Assetant NAxcy SHUSA, Minotity Staff Aesstant STAFI INVESTIOATIVE GROUP GEOROz R. BRDzs, Staff ConsuItant Ivo J. SPALATIN, Subcommittee Staff Direetor THOMAS R. SxzzTom, Minority Staff Consultant/Spe~oal I'roleots it -CONTENTS WITNESSES Page May 15, 1979: Tuesday, -.- 10 George R. Berdes, staff consultant, Committee on Foreign Affairs- Subcommittee on International Security Ivo J. Spalatin, staff director, 33 and Scientific Affairs, Committee on Foreign Affairs ------------ Thomas R. -

James Arthur Ray: New Age Guru and Sweat Lodge Culprit

SI March April 2010 pgs:SI J A 2009 1/22/10 11:39 AM Page 19 NOTES OF A FRINGE WATCHER M A R T I N G A R D N E R James Arthur Ray: New Age Guru and Sweat Lodge Culprit n recent years Sedona, Arizona, has become a popular haven for New IAge cults of all shades. Why Sedona? Partly because of its superb scenery and sunlight, and partly because of the belief that it swarms with invisible “vortexes” from which one can draw cosmic or spiritual energy. There are also nearby Indian tribes with herbal remedies and powerful witch doctors. On October 8, 2009, at a New Age retreat in Angel Valley, Arizona, near Sedona, another of Oprah Winfrey’s and Larry King’s guests ran into deep trouble. More than sixty followers of James Arthur Ray were crammed into a small tent Ray brought to an unbearable tem- perature with heated rocks. At the end of the first session of what Ray calls a “sweat lodge” meeting, guests were throwing up and passing out while Ray stood guard at the tent’s flap entrance to prevent guests from leaving. By the meeting’s end, some twenty followers were taken to hospitals where three died: Kirby Brown, thirty- eight; Liz Newman, forty-eight; and James Shore, forty. Who the devil is James Ray? He was Martin Gardner is author of more than sev- enty books, most recently The Jinn from Hyperspace (Prometheus Books, 2008) and When You Were a Tadpole and I Was a Fish, and Other Specula tions About This and That (Hill and Wang, 2009). -

Peoples Temple Miscellany, 1951-2013, MS 4126

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt9j49s3fd No online items Finding aid to Peoples Temple miscellany, 1951-2013, MS 4126 Finding aid prepared by Frances Wratten Kaplan California Historical Society 2011 678 Mission Street San Francisco, CA 94105 [email protected] URL: http://californiahistoricalsociety.org/ Finding aid to Peoples Temple MS 4126 1 miscellany, 1951-2013, MS 4126 Contributing Institution: California Historical Society Title: Peoples Temple miscellany Identifier/Call Number: MS 4126 Physical Description: 17.0 boxes Date (inclusive): 1951-2013 Collection is stored onsite. Language of Material: Collection materials are in English. Abstract: Peoples Temple miscellany consists of miscellaneous materials about Peoples Temple arranged by California Historical Society staff into a single, ongoing collection. Acquired at different times from a variety of donors, materials in the collection include correspondence, notes, scrapbooks, journals, clippings, publications, audio recordings, realia and television documentaries about Peoples Temple and Jonestown, its agricultural mission in Guyana. Access Collection is open for research. Publication Rights All requests to reproduce, publish, quote from or otherwise use collection materials must be submitted in writing to the Director of the Library and Archives, North Baker Research Library, California Historical Society, 678 Mission Street, San Francisco, CA 94105. Consent is given on behalf of the California Historical Society as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission from the copyright owner. Such permission must be obtained from the copyright owner. Restrictions also apply to digital representations of the original materials. Use of digital files is restricted to research and educational purposes. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Peoples Temple miscellany, MS 4126, California Historical Society Separated Materials Photographs have been removed and transferred to Photographs from Peoples Temple miscellany, 1966-1978, MSP 4126.