UCLA Previously Published Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uts Marine Biology Fact Sheet

UTS MARINE BIOLOGY FACT SHEET Topic: Phytoplankton and Cloud Formation 1.The CLAW Hypothesis Background: In 1987 four people (Charlson, Lovelock, Andrea, & Warren) introduced a theory that a natural gas called Dimethylsulfide (DMS), produced by microscopic plants in the ocean (phytoplankton), was a major contributor to the formation of clouds in the atmosphere. This theory was named the CLAW Hypothesis (from the first letter of each of their surnames). Fast facts: . Phytoplankton produce DMSP (dimethylsulphoniopropionate), an organic sulphur compound, which is converted to DMS in the ocean. The majority of this DMS is consumed by bacteria but around 10% escapes into the atmosphere. When DMS is released into the air, a chemical reaction takes place (called an oxidation reaction) and sulphate aerosols are formed – a gas which acts as cloud condensation nuclei (CCN). This means it combines with water droplets in the atmosphere to form clouds. As a result, more clouds increase the reflectivity of the sun’s rays (earth albedo) which decreases the amount of light reaching the earth’s surface, and contributes to cooling the overall climate. A decrease in light causes a decrease in phytoplankton productivity of DMS. (Phytoplankton are primary producers which rely on light to function). This sequence of events is called a Negative Feedback Loop, because phytoplankton increase DMS production but DMS forms clouds which lowers the amount of light reaching the earth, resulting in less phytoplankton and less DMS. DMS emissions are a key step in the global sulphur cycle, which circulates sulphur throughout the earth, oceans, and atmosphere. It is an essential component in the growth of all living things. -

M1 Project: Climate - Biosphere Interactions Using ODE Models

M1 Project: Climate - Biosphere interactions using ODE models Jan Rombouts Erasmus Mundus Master in Complex Systems Science Ecole´ Polytechnique, Paris Supervisors: Michael Ghil, Regis Ferri`ere Ecole´ Normal Sup´erieure,Paris June 30, 2014 Abstract There are many examples of the complex interactions of climate and vegetation through various feedback mechanisms. Climatic models have begun to take into ac- count vegetation as an important player in the evolution of the climate. Climate models range from complicated, large scale GCMs to simple conceptual models. It is this last type of modeling that I looked at in my project. Conceptual models usually use differential equations and techniques from dynamical systems theory to investi- gate basic mechanisms in the climate system. They have in particular been applied to investigate glacial-interglacial cycles. These models have not often included vege- tation as one of their variables, and this is what I've looked at in the project. First I investigate a simple, two equation model, and show that even in such a simple model, interesting oscillatory behaviour can be observed. Then I go on to study models with three equations, based on an existing model for temperature and ice sheet evolution. I extend this model in two ways: by adding a vegetation variable, and by adding a carbon dioxide variable. Again, oscillations are observed, but the existence depends on parameters that are linked to the vegetation. Finally I put it all together in a model with four equations. These models show that vegetation is an important factor, and can account for some specific features of glacial-interglacial cycles. -

The Case Against Climate Regulation Via Oceanic Phytoplankton Sulphur Emissions P

REVIEW doi:10.1038/nature10580 The case against climate regulation via oceanic phytoplankton sulphur emissions P. K. Quinn1 & T. S. Bates1 More than twenty years ago, a biological regulation of climate was proposed whereby emissions of dimethyl sulphide from oceanic phytoplankton resulted in the formation of aerosol particles that acted as cloud condensation nuclei in the marine boundary layer. In this hypothesis—referred to as CLAW—the increase in cloud condensation nuclei led to an increase in cloud albedo with the resulting changes in temperature and radiation initiating a climate feedback altering dimethyl sulphide emissions from phytoplankton. Over the past two decades, observations in the marine boundary layer, laboratory studies and modelling efforts have been conducted seeking evidence for the CLAW hypothesis. The results indicate that a dimethyl sulphide biological control over cloud condensation nuclei probably does not exist and that sources of these nuclei to the marine boundary layer and the response of clouds to changes in aerosol are much more complex than was recognized twenty years ago. These results indicate that it is time to retire the CLAW hypothesis. loud condensation nuclei (CCN) can affect the amount of solar The CLAW hypothesis further postulated that an increase in DMS radiation reaching Earth’s surface by altering cloud droplet emissions from the ocean would result in an increase in CCN, cloud number concentration and size and, as a result, cloud reflectivity droplet concentrations, and cloud albedo, and a decrease in the amount C 1 or albedo . CCN are atmospheric particles that are sufficiently soluble of solar radiation reaching Earth’s surface. -

Enhancing the Natural Sulfur Cycle to Slow Global Warming$

ARTICLE IN PRESS Atmospheric Environment 41 (2007) 7373–7375 www.elsevier.com/locate/atmosenv New Directions: Enhancing the natural sulfur cycle to slow global warming$ Full scale ocean iron fertilization of the Southern The CLAW hypothesis further states that greater Ocean (SO) has been proposed previously as a DMS production would result in additional flux to means to help mitigate rising CO2 in the atmosphere the atmosphere, more cloud condensation nuclei (Martin et al., 1990, Nature 345, 156–158). Here we (CCN) and greater cloud reflectivity by decreasing describe a different, more leveraged approach to cloud droplet size. Thus, increased DMS would partially regulate climate using limited iron en- contribute to the homeostasis of the planet by hancement to stimulate the natural sulfur cycle, countering warming from increasing CO2. A cor- resulting in increased cloud reflectivity that could ollary to the CLAW hypothesis is that elevated CO2 cool large regions of our planet. Some regions of the itself increases DMS production which has been Earth’s oceans are high in nutrients but low in observed during a mesocosm scale CO2 enrichment primary productivity. The largest such region is the experiment (Wingenter et al., 2007, Geophysical SO followed by the equatorial Pacific. Several Research Letters 34, L05710). The CLAW hypoth- mesoscale (102 km2) experiments have shown that esis relies on the assumption that DMS sea-to-air the limiting nutrient to productivity is iron. Yet, the flux leads to new particles and not just the growth of effectiveness of iron fertilization for sequestering existing particles. If the CLAW hypothesis is significant amounts of atmospheric CO2 is still in correct, the danger is that enormous anthropogenic question. -

Effects of Increased Pco2 and Temperature on the North Atlantic Spring Bloom. III. Dimethylsulfoniopropionate

Vol. 388: 41–49, 2009 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published August 19 doi: 10.3354/meps08135 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Effects of increased pCO2 and temperature on the North Atlantic spring bloom. III. Dimethylsulfoniopropionate Peter A. Lee1,*, Jamie R. Rudisill1, Aimee R. Neeley1, 7, Jennifer M. Maucher2, David A. Hutchins3, 8, Yuanyuan Feng3, 8, Clinton E. Hare3, Karine Leblanc3, 9,10, Julie M. Rose3,11, Steven W. Wilhelm4, Janet M. Rowe4, 5, Giacomo R. DiTullio1, 6 1Hollings Marine Laboratory, College of Charleston, 331 Fort Johnson Road, Charleston, South Carolina 29412, USA 2Center for Coastal Environmental Health and Biomolecular Research, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 219 Fort Johnson Road, Charleston, South Carolina 29412, USA 3College of Marine and Earth Studies, University of Delaware, 700 Pilottown Road, Lewes, Delaware 19958, USA 4Department of Microbiology, University of Tennessee, 1414 West Cumberland Ave, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996, USA 5Department of Plant Pathology, The University of Nebraska, 205 Morrison Center, Lincoln, Nebraska 68583, USA 6Grice Marine Laboratory, College of Charleston, 205 Fort Johnson Road, Charleston, South Carolina 29412, USA 7Present address: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Calibration and Validation Office, 1450 S. Rolling Road, Suite 4.111, Halethorpe, Maryland 21227, USA 8Present address: Department of Biological Sciences, University of Southern California, 3616 Trousdale Parkway, Los Angeles, California 90089, USA 9Present address: Aix-Marseille Université, CNRS, -

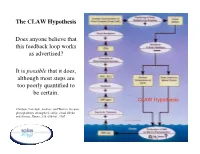

The CLAW Hypothesis Does Anyone Believe That This Feedback Loop

The CLAW Hypothesis Does anyone believe that this feedback loop works as advertised? It is possible that it does, although most steps are too poorly quantified to be certain. CLAW Hypothesis Charlson, Lovelock, Andreae, and Warren, Oceanic phytoplankton, atmospheric sulfur, cloud albedo and climate, Nature, 326, 655-661, 1987. The CLAW Hypothesis DMS fluxes probably control the growth of aerosols into the CCN size range. These CCN help control the radiative properties of stratocumulus clouds. Although CLAW has not been rigorously proven, it is extremely likely that biological processes are linked to cloud properties via sulfur-containing aerosols. Neither can be understood in CLAW Hypothesis isolation from the other. What role do aerosols play in creating these pockets of open cells, POCs? To improve models of this region, we need to quantify the factors controlling clouds and radiation. 2-300 Wm-2 Difference! This aerosol data from an EPIC cruise shows the loss of aerosols when a POC passes overhead. Tony Clarke observed this re-growth from freshly-nucleated particles in the Eastern Pacific MBL during PEM-Tropics. Drizzle Removal > Nucleation > DMS-Controlled Growth is one plausible explanation for several-day POC lifetimes. How much of the recovery is from entrainment vs growth? POC Data courtesy Fairall & Collins The upwelling of cold, nutrient rich deep water creates gradients in biological productivity that should translate into gradients of DMS emissions and other . We can exploit these gradients to study the factors controlling fluxes, aerosol chemistry, and cloud properties. In the remote marine atmosphere the supply of DMS and its oxidation mechanisms limit the rates of new particle nucleation and growth. -

Decreasing Particle Number Concentrations in a Warming Atmosphere and Implications F

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss., 11, 27913–27936, 2011 Atmospheric www.atmos-chem-phys-discuss.net/11/27913/2011/ Chemistry doi:10.5194/acpd-11-27913-2011 and Physics © Author(s) 2011. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Discussions This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics (ACP). Please refer to the corresponding final paper in ACP if available. Decreasing particle number concentrations in a warming atmosphere and implications F. Yu1, G. Luo1, R. P. Turco2, J. A. Ogren3, and R. M. Yantosca4 1Atmospheric Sciences Research Center, State University of New York at Albany, USA 2Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, University of California at Los Angeles, USA 3Global Monitoring Division (GMD), Earth System Research Laboratory (ESRL), NOAA, USA 4School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, USA Received: 22 August 2011 – Accepted: 29 September 2011 – Published: 14 October 2011 Correspondence to: F. Yu ([email protected]) Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. 27913 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract New particle formation contributes significantly to the number concentration of conden- sation nuclei (CN) as well as cloud CN (CCN), a key factor determining aerosol indirect radiative forcing of the climate system. Using a physics-based nucleation mechanism 5 that is consistent with a range of field observations of aerosol formation, it is shown that projected increases in global temperatures could significantly inhibit new particle, and CCN, formation rates worldwide. An analysis of CN concentrations observed at four NOAA ESRL/GMD baseline stations since the 1970s and two other sites since 1990s reveals long-term decreasing trends consistent with these predictions. -

Contents in Context Environmental Chemistry, Vol. 4(6)

Contents in Context Environmental Chemistry,Vol. 4(6), 2007 Investigating the current thinking on the CLAW Hypothesis Jill M. Cainey Environ. Chem. 2007, 4, 365 This issue of Environmental Chemistry focuses on the research arising from the publication of the ‘CLAW Hypothesis’, a paper published over 20 years ago in Nature. This paper suggested a potential role for sulfur emissions from phytoplankton in modifying cloud albedo and hence climate. The CLAW hypothesis: a review of the major developments Greg P.Ayers and Jill M. Cainey Environ. Chem. 2007, 4, 366 Understanding the role of clouds in the warming and the cooling of the planet and how that role alters in a warming world is one of the biggest uncertainties climate change researchers face. Important in this regard is the influence on cloud properties of cloud condensation nuclei, the tiny atmospheric particles necessary for the nucleation of every single cloud droplet. The anthropogenic contribution to cloud condensation nuclei is known to be large in some regions through knowledge of pollutant emissions; however, the natural processes that regulate cloud condensation nuclei over large parts of the globe are less well understood. The CLAW hypothesis provides a mechanism by which plankton may modify climate through the atmospheric sulfur cycle via the provision of sulfate cloud condensation nuclei. The CLAW hypothesis was published over 20 years ago and has stimulated a great deal of research. Do I believe in CLAW? Barry Huebert Environ. Chem. 2007, 4, 375 In 1987 Charlson, Lovelock, Andreae and Warren revolutionised the way we think about the Earth when they argued that marine algae, atmospheric particulate matter and clouds might be linked in such a way that they could work like a planetary thermostat. -

Sulphate-Climate Coupling Over the Past 300,000 Years in Inland Antarctica

Title Sulphate-climate coupling over the past 300,000 years in inland Antarctica Iizuka, Yoshinori; Uemura, Ryu; Motoyama, Hideaki; Suzuki, Toshitaka; Miyake, Takayuki; Hirabayashi, Motohiro; Author(s) Hondoh, Takeo Nature, 490(7418), 81-84 Citation https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11359 Issue Date 2012-10-04 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/52663 Type article (author version) Additional Information There are other files related to this item in HUSCAP. Check the above URL. File Information Nat490-7418_81-84.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP Nature manuscript 2012-01-01306C Sulphate-climate coupling over the past 300,000 years in inland Antarctica Yoshinori Iizuka1, Ryu Uemura2, Hideaki Motoyama3, Toshitaka Suzuki4, Takayuki Miyake3,5, Motohiro Hirabayashi3 and Takeo Hondoh1 1 Institute of Low Temperature Science, Hokkaido University, Sapporo 060-0819, Japan 2 Department of Chemistry, Biology and Marine Science, Faculty of Science, University of the Ryukyus, Okinawa 903-0213, Japan 3 National Institute of Polar Research, Tokyo 190-8518, Japan 4 Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Science, Yamagata University, Yamagata 990-8560, Japan 5 now at: School of Environmental Science, The University of Shiga Prefecture, Shiga, 522-8533, Japan 1 Nature manuscript 2012-01-01306C Sulphate aerosols, particularly micron-sized particles of sulphate salt and sulphate-adhered dust, can act as cloud condensation nuclei (CCN), leading to increased solar scattering that cools Earth's climate1-2. Global climate, according to the "CLAW" hypothesis3, may be regulated by marine phytoplankton in a negative feedback loop composed of temperature, cloud albedo, and sulphate production. -

Lovejoy, S. , 2015

A voyage through scales, a missing quadrillion and why the climate is not what you expect S. Lovejoy Climate Dynamics Observational, Theoretical and Computational Research on the Climate System ISSN 0930-7575 Volume 44 Combined 11-12 Clim Dyn (2015) 44:3187-3210 DOI 10.1007/s00382-014-2324-0 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer- Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy Clim Dyn (2015) 44:3187–3210 DOI 10.1007/s00382-014-2324-0 A voyage through scales, a missing quadrillion and why the climate is not what you expect S. Lovejoy Received: 7 February 2014 / Accepted: 3 September 2014 / Published online: 11 October 2014 © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014 Abstract Using modern climate data and paleodata, we with the help of the new, pedagogical “H model”. Both voyage through 17 orders of magnitude in scale explic- deterministic General Circulation Models (GCM’s) with itly displaying the astounding temporal variability of the fixed forcings (“control runs”) and stochastic turbulence- atmosphere from fractions of a second to hundreds of mil- based models reproduce weather and macroweather, but lions of years. -

The Influence of Ocean Acidification and Warming on DMSP & DMS in New Zealand Coastal Water

atmosphere Article The Influence of Ocean Acidification and Warming on DMSP & DMS in New Zealand Coastal Water Alexia D. Saint-Macary 1,2,* , Neill Barr 1, Evelyn Armstrong 1,3 , Karl Safi 4, Andrew Marriner 1, Mark Gall 1, Kiri McComb 5, Peter W. Dillingham 6 and Cliff S. Law 1,2 1 National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, Wellington 6021, New Zealand; [email protected] (N.B.); [email protected] (E.A.); [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (M.G.); [email protected] (C.S.L.) 2 Department of Marine Science, University of Otago, Dunedin 9016, New Zealand 3 Department of Chemistry, University of Otago Centre for Oceanography, Dunedin 9016, New Zealand 4 National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, Hamilton 3216, New Zealand; karl.safi@niwa.co.nz 5 Department of Chemistry, University of Otago, Dunedin 9016, New Zealand; [email protected] 6 Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Otago, Dunedin 9016, New Zealand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The cycling of the trace gas dimethyl sulfide (DMS) and its precursor dimethylsulfonio- propionate (DMSP) may be affected by future ocean acidification and warming. DMSP and DMS concentrations were monitored over 20-days in four mesocosm experiments in which the temperature and pH of coastal water were manipulated to projected values for the year 2100 and 2150. This had no effect on DMSP in the two-initial nutrient-depleted experiments; however, in the two nutrient- amended experiments, warmer temperature combined with lower pH had a more significant effect Citation: Saint-Macary, A.D.; Barr, on DMSP & DMS concentrations than lower pH alone. -

Articles Ply of Nutrients to the Ocean, and the Albedo of Snow and on Ice and Snow Impacts the Surface Albedo and Absorption Ice

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 1701–1737, 2010 www.atmos-chem-phys.net/10/1701/2010/ Atmospheric © Author(s) 2010. This work is distributed under Chemistry the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. and Physics A review of natural aerosol interactions and feedbacks within the Earth system K. S. Carslaw1, O. Boucher2, D. V. Spracklen1, G. W. Mann1, J. G. L. Rae2, S. Woodward2, and M. Kulmala3 1School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK 2Met Office Hadley Centre, FitzRoy Road, Exeter, UK 3University of Helsinki, Department of Physics, Division of Atmospheric Sciences and Geophysics, Helsinki, Finland Received: 7 April 2009 – Published in Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss.: 5 May 2009 Revised: 11 December 2009 – Accepted: 18 January 2010 – Published: 15 February 2010 Abstract. The natural environment is a major source of at- 1 Introduction mospheric aerosols, including dust, secondary organic ma- terial from terrestrial biogenic emissions, carbonaceous par- Aerosols are important components of most parts of the Earth ticles from wildfires, and sulphate from marine phytoplank- system. In the atmosphere, they affect the radiative balance ton dimethyl sulphide emissions. These aerosols also have by scattering and absorbing radiation and affecting the prop- a significant effect on many components of the Earth sys- erties of clouds (Haywood and Boucher, 2000; Lohmann and tem such as the atmospheric radiative balance and photosyn- Feichter, 2005; Forster et al., 2007). In the cryosphere, de- thetically available radiation entering the biosphere, the sup- position of light absorbing carbonaceous and dust particles ply of nutrients to the ocean, and the albedo of snow and on ice and snow impacts the surface albedo and absorption ice.