Activities | Grades 6–8 EXPLORING a COMPLEX SPACE-FILLING SHAPE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Build a Tetrahedral Kite

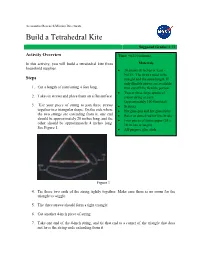

Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate Build a Tetrahedral Kite Suggested Grades: 8-12 Activity Overview Time: 90-120 minutes In this activity, you will build a tetrahedral kite from Materials household supplies. • 24 straws (8 inches or less) - NOTE: The straws need to be Steps straight and the same length. If only flexible straws are available, 1. Cut a length of yarn/string 4 feet long. then cut off the flexible portion. • Two or three large spools of 2. Take six straws and place them on a flat surface. cotton string or yarn (approximately 100 feet total) 3. Use your piece of string to join three straws • Scissors together in a triangular shape. On the side where • Hot glue gun and hot glue sticks the two strings are extending from it, one end • Ruler or dowel rod for kite bridle should be approximately 20 inches long, and the • Four pieces of tissue paper (24 x other should be approximately 4 inches long. 18 inches or larger) See Figure 1. • All-purpose glue stick Figure 1 4. Tie these two ends of the string tightly together. Make sure there is no room for the triangle to wiggle. 5. The three straws should form a tight triangle. 6. Cut another 4-inch piece of string. 7. Take one end of the 4-inch string, and tie that end to a corner of the triangle that does not have the string ends extending from it. Figure 2. 8. Add two more straws onto the longest piece of string. 9. Next, take the string that holds the two additional straws and tie it to the end of one of the 4-inch strings to make another tight triangle. -

THE GEOMETRY of PYRAMIDS One of the More Interesting Solid

THE GEOMETRY OF PYRAMIDS One of the more interesting solid structures which has fascinated individuals for thousands of years going all the way back to the ancient Egyptians is the pyramid. It is a structure in which one takes a closed curve in the x-y plane and connects straight lines between every point on this curve and a fixed point P above the centroid of the curve. Classical pyramids such as the structures at Giza have square bases and lateral sides close in form to equilateral triangles. When the closed curve becomes a circle one obtains a cone and this cone becomes a cylindrical rod when point P is moved to infinity. It is our purpose here to discuss the properties of all N sided pyramids including their volume and surface area using only elementary calculus and geometry. Our starting point will be the following sketch- The base represents a regular N sided polygon with side length ‘a’ . The angle between neighboring radial lines r (shown in red) connecting the polygon vertices with its centroid is θ=2π/N. From this it follows, by the law of cosines, that the length r=a/sqrt[2(1- cos(θ))] . The area of the iscosolis triangle of sides r-a-r is- a a 2 a 2 1 cos( ) A r 2 T 2 4 4 (1 cos( ) From this we have that the area of the N sided polygon and hence the pyramid base will be- 2 2 1 cos( ) Na A N base 2 4 1 cos( ) N 2 It readily follows from this result that a square base N=4 has area Abase=a and a hexagon 2 base N=6 yields Abase= 3sqrt(3)a /2. -

Math 366 Lecture Notes Section 11.4 – Geometry in Three Dimensions

Section 11-4 Math 366 Lecture Notes Section 11.4 – Geometry in Three Dimensions Simple Closed Surfaces A simple closed surface has exactly one interior, no holes, and is hollow. A sphere is the set of all points at a given distance from a given point, the center . A sphere is a simple closed surface. A solid is a simple closed surface with all interior points. (see p. 726) A polyhedron is a simple closed surface made up of polygonal regions, or faces . The vertices of the polygonal regions are the vertices of the polyhedron, and the sides of each polygonal region are the edges of the polyhedron. (see p. 726-727) A prism is a polyhedron in which two congruent faces lie in parallel planes and the other faces are bounded by parallelograms. The parallel faces of a prism are the bases of the prism. A prism is usually names after its bases. The faces other than the bases are the lateral faces of a prism. A right prism is one in which the lateral faces are all bounded by rectangles. An oblique prism is one in which some of the lateral faces are not bounded by rectangles. To draw a prism: 1) Draw one of the bases. 2) Draw vertical segments of equal length from each vertex. 3) Connect the bottom endpoints to form the second base. Use dashed segments for edges that cannot be seen. A pyramid is a polyhedron determined by a polygon and a point not in the plane of the polygon. The pyramid consists of the triangular regions determined by the point and each pair of consecutive vertices of the polygon and the polygonal region determined by the polygon. -

VOLUME of POLYHEDRA USING a TETRAHEDRON BREAKUP We

VOLUME OF POLYHEDRA USING A TETRAHEDRON BREAKUP We have shown in an earlier note that any two dimensional polygon of N sides may be broken up into N-2 triangles T by drawing N-3 lines L connecting every second vertex. Thus the irregular pentagon shown has N=5,T=3, and L=2- With this information, one is at once led to the question-“ How can the volume of any polyhedron in 3D be determined using a set of smaller 3D volume elements”. These smaller 3D eelements are likely to be tetrahedra . This leads one to the conjecture that – A polyhedron with more four faces can have its volume represented by the sum of a certain number of sub-tetrahedra. The volume of any tetrahedron is given by the scalar triple product |V1xV2∙V3|/6, where the three Vs are vector representations of the three edges of the tetrahedron emanating from the same vertex. Here is a picture of one of these tetrahedra- Note that the base area of such a tetrahedron is given by |V1xV2]/2. When this area is multiplied by 1/3 of the height related to the third vector one finds the volume of any tetrahedron given by- x1 y1 z1 (V1xV2 ) V3 Abs Vol = x y z 6 6 2 2 2 x3 y3 z3 , where x,y, and z are the vector components. The next question which arises is how many tetrahedra are required to completely fill a polyhedron? We can arrive at an answer by looking at several different examples. Starting with one of the simplest examples consider the double-tetrahedron shown- It is clear that the entire volume can be generated by two equal volume tetrahedra whose vertexes are placed at [0,0,sqrt(2/3)] and [0,0,-sqrt(2/3)]. -

The Mars Pentad Time Pyramids the Quantum Space Time Fractal Harmonic Codex the Pentagonal Pyramid

The Mars Pentad Time Pyramids The Quantum Space Time Fractal Harmonic Codex The Pentagonal Pyramid Abstract: Early in this author’s labors while attempting to create the original Mars Pentad Time Pyramids document and pyramid drawings, a failure was experienced trying to develop a pentagonal pyramid with some form of tetrahedral geometry. This pentagonal pyramid is now approached again and refined to this tetrahedral criteria, creating tetrahedral angles in the pentagonal pyramid, and pentagonal [54] degree angles in the pentagon base for the pyramid. In the process another fine pentagonal pyramid was developed with pure pentagonal geometries using the value for ancient Egyptian Pyramid Pi = [22 / 7] = [aPi]. Also used is standard modern Pi and modern Phi in one of the two pyramids shown. Introduction: Achieved are two Pentagonal Pyramids: One creates tetrahedral angle [54 .735~] in the Side Angle {not the Side Face Angle}, using a novel height of the value of tetrahedral angle [19 .47122061] / by [5], and then the reverse tetrahedral angle is accomplished with the same tetrahedral [19 .47122061] angle value as the height, but “Harmonic Codexed” to [1 .947122061]! This achievement of using the second height mentioned, proves aspects of the Quantum Space Time Fractal Harmonic Codex. Also used is Height = [2], which replicates the [36] and [54] degree angles in the pentagon base to the Side Angles of the Pentagonal Pyramid. I have come to understand that there is not a “perfect” pentagonal pyramid. No matter what mathematical constants or geometry values used, there will be a slight factor of error inherent in the designs trying to attain tetrahedra. -

Cons=Ucticn (Process)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 038 271 SE 007 847 AUTHOR Wenninger, Magnus J. TITLE Polyhedron Models for the Classroom. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, Inc., Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 68 NOTE 47p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of Mathematics,1201 16th St., N.V., Washington, D.C. 20036 ED RS PRICE EDRS Pr:ce NF -$0.25 HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Cons=ucticn (Process), *Geometric Concepts, *Geometry, *Instructional MateriAls,Mathematical Enrichment, Mathematical Models, Mathematics Materials IDENTIFIERS National Council of Teachers of Mathematics ABSTRACT This booklet explains the historical backgroundand construction techniques for various sets of uniformpolyhedra. The author indicates that the practical sianificanceof the constructions arises in illustrations for the ideas of symmetry,reflection, rotation, translation, group theory and topology.Details for constructing hollow paper models are provided for thefive Platonic solids, miscellaneous irregular polyhedra and somecompounds arising from the stellation process. (RS) PR WON WITHMICROFICHE AND PUBLISHER'SPRICES. MICROFICHEREPRODUCTION f ONLY. '..0.`rag let-7j... ow/A U.S. MOM Of NUM. INCIII01 a WWII WIC Of MAW us num us us ammo taco as mums NON at Ot Widel/A11011 01116111111 IT.P01115 OF VOW 01 OPENS SIAS SO 101 IIKISAMIT IMRE Offlaat WC Of MANN POMO OS POW. OD PROCESS WITH MICROFICHE AND PUBLISHER'S PRICES. reit WeROFICHE REPRODUCTION Pvim ONLY. (%1 00 O O POLYHEDRON MODELS for the Classroom MAGNUS J. WENNINGER St. Augustine's College Nassau, Bahama. rn ErNATIONAL COUNCIL. OF Ka TEACHERS OF MATHEMATICS 1201 Sixteenth Street, N.W., Washington, D. C. 20036 ivetmIssromrrIPRODUCE TmscortnIGMED Al"..Mt IAL BY MICROFICHE ONLY HAS IEEE rano By Mat __Comic _ TeachMar 10 ERIC MID ORGANIZATIONS OPERATING UNSER AGREEMENTS WHIM U. -

Pentagonal Pyramid

Chapter 9 Surfaces and Solids Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. Pyramids, Area, and 9.2 Volume Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. Pyramids, Area, and Volume The solids (space figures) shown in Figure 9.14 below are pyramids. In Figure 9.14(a), point A is noncoplanar with square base BCDE. In Figure 9.14(b), F is noncoplanar with its base, GHJ. (a) (b) Figure 9.14 3 Pyramids, Area, and Volume In each space pyramid, the noncoplanar point is joined to each vertex as well as each point of the base. A solid pyramid results when the noncoplanar point is joined both to points on the polygon as well as to points in its interior. Point A is known as the vertex or apex of the square pyramid; likewise, point F is the vertex or apex of the triangular pyramid. The pyramid of Figure 9.14(b) has four triangular faces; for this reason, it is called a tetrahedron. 4 Pyramids, Area, and Volume The pyramid in Figure 9.15 is a pentagonal pyramid. It has vertex K, pentagon LMNPQ for its base, and lateral edges and Although K is called the vertex of the pyramid, there are actually six vertices: K, L, M, N, P, and Q. Figure 9.15 The sides of the base and are base edges. 5 Pyramids, Area, and Volume All lateral faces of a pyramid are triangles; KLM is one of the five lateral faces of the pentagonal pyramid. Including base LMNPQ, this pyramid has a total of six faces. The altitude of the pyramid, of length h, is the line segment from the vertex K perpendicular to the plane of the base. -

Can Every Face of a Polyhedron Have Many Sides ?

Can Every Face of a Polyhedron Have Many Sides ? Branko Grünbaum Dedicated to Joe Malkevitch, an old friend and colleague, who was always partial to polyhedra Abstract. The simple question of the title has many different answers, depending on the kinds of faces we are willing to consider, on the types of polyhedra we admit, and on the symmetries we require. Known results and open problems about this topic are presented. The main classes of objects considered here are the following, listed in increasing generality: Faces: convex n-gons, starshaped n-gons, simple n-gons –– for n ≥ 3. Polyhedra (in Euclidean 3-dimensional space): convex polyhedra, starshaped polyhedra, acoptic polyhedra, polyhedra with selfintersections. Symmetry properties of polyhedra P: Isohedron –– all faces of P in one orbit under the group of symmetries of P; monohedron –– all faces of P are mutually congru- ent; ekahedron –– all faces have of P the same number of sides (eka –– Sanskrit for "one"). If the number of sides is k, we shall use (k)-isohedron, (k)-monohedron, and (k)- ekahedron, as appropriate. We shall first describe the results that either can be found in the literature, or ob- tained by slight modifications of these. Then we shall show how two systematic ap- proaches can be used to obtain results that are better –– although in some cases less visu- ally attractive than the old ones. There are many possible combinations of these classes of faces, polyhedra and symmetries, but considerable reductions in their number are possible; we start with one of these, which is well known even if it is hard to give specific references for precisely the assertion of Theorem 1. -

Unit 6 Visualising Solid Shapes(Final)

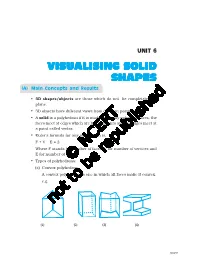

• 3D shapes/objects are those which do not lie completely in a plane. • 3D objects have different views from different positions. • A solid is a polyhedron if it is made up of only polygonal faces, the faces meet at edges which are line segments and the edges meet at a point called vertex. • Euler’s formula for any polyhedron is, F + V – E = 2 Where F stands for number of faces, V for number of vertices and E for number of edges. • Types of polyhedrons: (a) Convex polyhedron A convex polyhedron is one in which all faces make it convex. e.g. (1) (2) (3) (4) 12/04/18 (1) and (2) are convex polyhedrons whereas (3) and (4) are non convex polyhedron. (b) Regular polyhedra or platonic solids: A polyhedron is regular if its faces are congruent regular polygons and the same number of faces meet at each vertex. For example, a cube is a platonic solid because all six of its faces are congruent squares. There are five such solids– tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, dodecahedron and icosahedron. e.g. • A prism is a polyhedron whose bottom and top faces (known as bases) are congruent polygons and faces known as lateral faces are parallelograms (when the side faces are rectangles, the shape is known as right prism). • A pyramid is a polyhedron whose base is a polygon and lateral faces are triangles. • A map depicts the location of a particular object/place in relation to other objects/places. The front, top and side of a figure are shown. Use centimetre cubes to build the figure. -

Classroom Capsules

CLASSROOM CAPSULES EDITOR Michael K. Kinyon Indiana University South Bend South Bend, IN 46634 Classroom Capsules consists primarily of short notes (1–3 pages) that convey new mathematical in- sights and effective teaching strategies for college mathematics instruction. Please submit manuscripts prepared according to the guidelines on the inside front cover to the Editor, Michael K. Kinyon, Indiana University South Bend, South Bend, IN 46634. The Theorem of Cosines for Pyramids Alexander Kheyfits (alexander.kheyfi[email protected]), Bronx Community College, CUNY, Bronx, NY 10453 The classical three-millennia-old Pythagorean theorem is still irresistibly attractive for lovers of mathematics—see, for example, [1] or a recent survey [8] for its numer- ous old and new generalizations. It can be extended to 3-space in various ways. A straightforward extension states that the square of a diagonal of a right rectangular parallelepiped is equal to the sum of squares of its adjacent edges. A less trivial gener- alization is the following result, which can be found in good collections of geometric problems as well as in a popular calculus textbook [7, p. 858]: (PTT) The Pythagorean theorem for tetrahedra with a trirectangular ver- tex. In a tetrahedron with a trirectangular vertex, the square of the area of the op- posite face to this vertex is equal to the sum of the squares of the areas of three other faces. Consider a triangle with sides a, b, c and the angle C opposite side c. The classical Pythagorean theorem is a particular case of the Theorem or Law of Cosines, c2 = a2 + b2 − 2ab cos C, if we specify here C to be a right angle. -

Putting the Icosahedron Into the Octahedron

Forum Geometricorum Volume 17 (2017) 63–71. FORUM GEOM ISSN 1534-1178 Putting the Icosahedron into the Octahedron Paris Pamfilos Abstract. We compute the dimensions of a regular tetragonal pyramid, which allows a cut by a plane along a regular pentagon. In addition, we relate this construction to a simple construction of the icosahedron and make a conjecture on the impossibility to generalize such sections of regular pyramids. 1. Pentagonal sections The present discussion could be entitled Organizing calculations with Menelaos, and originates from a problem from the book of Sharygin [2, p. 147], in which it is required to construct a pentagonal section of a regular pyramid with quadrangular F J I D T L C K H E M a x A G B U V Figure 1. Pentagonal section of quadrangular pyramid basis. The basis of the pyramid is a square of side-length a and the pyramid is assumed to be regular, i.e. its apex F is located on the orthogonal at the center E of the square at a distance h = |EF| from it (See Figure 1). The exercise asks for the determination of the height h if we know that there is a section GHIJK of the pyramid by a plane which is a regular pentagon. The section is tacitly assumed to be symmetric with respect to the diagonal symmetry plane AF C of the pyramid and defined by a plane through the three points K, G, I. The first two, K and G, lying symmetric with respect to the diagonal AC of the square. -

DETECTION of FACES in WIRE-FRAME POLYHEDRA Interactive Modelling of Uniform Polyhedra

DETECTION OF FACES IN WIRE-FRAME POLYHEDRA Interactive Modelling of Uniform Polyhedra Hidetoshi Nonaka Hokkaido University, N14W9, Sapporo, 060 0814, Japan Keywords: Uniform polyhedron, polyhedral graph, simulated elasticity, interactive computing, recreational mathematics. Abstract: This paper presents an interactive modelling system of uniform polyhedra including regular polyhedra, semi-regular polyhedra, and intersected concave polyhedra. In our system, user can virtually “make” and “handle” them interactively. The coordinate of vertices are computed without the knowledge of faces, solids, or metric information, but only with the isomorphic graph structure. After forming a wire-frame polyhedron, the faces are detected semi-automatically through user-computer interaction. This system can be applied to recreational mathematics, computer assisted education of the graph theory, and so on. 1 INTRODUCTION 2 UNIFORM POLYHEDRA This paper presents an interactive modelling system 2.1 Platonic Solids of uniform polyhedra using simulated elasticity. Uniform polyhedra include five regular polyhedra Five Platonic solids are listed in Table 1. The (Platonic solids), thirteen semi-regular polyhedra symbol Pmn indicates that the number of faces (Archimedean solids), and four regular concave gathering around a vertex is n, and each face is m- polyhedra (Kepler-Poinsot solids). Alan Holden is describing in his writing, “The best way to learn sided regular polygon. about these objects is to make them, next best to handle them (Holden, 1971).” Traditionally, these Table 1: The list of Platonic solids. objects are made based on the shapes of faces or Symbol Polyhedron Vertices Edges Faces solids. Development figures and a set of regular polygons cut from card boards can be used to P33 Tetrahedron 4 6 4 assemble them.