Robert C. Knapp, John D. Mac Isaac]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE 3Rd CENTURY MILITARY EQUIPMENT in SOUTH-WESTERN SLOVENIA

The Roman army between the Alps and the Adriatic, Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 31 / Studia Alpium et Adriae I, 2016, 99–120 THE 3rd CENTURY MILITARY EQUIPMENT IN SOUTH-WESTERN SLOVENIA Jana HORVAT, Beatriče ŽBONA TRKMAN † Abstract The significant unrest that characterized the final decades of therd 3 century lead to intensive control over communication routes and to the fortification of the most important settlements in the south-eastern Alpine area. Two assemblages originat- ing from south-western Slovenia are presented to achieve a better understanding of the period. The hoard from Prelovce near Malovše dated to the second half of the 3rd century and consisted of horse harness decoration, a military belt, and a combat knife. The hoard may suggest army movement or military control of the main road. A group of sixteen graves was found in Javor near Dolnji Zemon, and the majority of them originate from the second half of the 3rd century. The grave goods in two graves indicate a military affiliation of the deceased; a female grave containing silver jewellery corroborates the special social position of the whole group. It is possible that a military detachment was stationed at Javor near Dolnji Zemon, and controlled the road from Tarsatica to the Postojna basin. Keywords: South-western Slovenia, second half of the 3rd century, Prelovce near Malovše, Javor near Dolnji Zemon, hoards, graves, horse harness decoration, combat knives, jewellery INTRODUCTION dated in the 320s.3 The fortress at Nauportus (Vrhnika) might date at the end of the 3rd century.4 On the basis of The final decades of the 3rd century are character- coin finds it is presumed that the principia in Tarsatica ized by increasing control over communication routes were constructed at the end of the 270s or during the and by the fortification of the most important settle- 280s.5 The short-lived Pasjak fortress on the Aquileia– ments in the south-eastern Alpine area. -

The Last Empire of Iran by Michael R.J

The Last Empire of Iran By Michael R.J. Bonner In 330 BCE, Alexander the Great destroyed the Persian imperial capital at Persepolis. This was the end of the world’s first great international empire. The ancient imperial traditions of the Near East had culminated in the rule of the Persian king Cyrus the Great. He and his successors united nearly all the civilised people of western Eurasia into a single state stretching, at its height, from Egypt to India. This state perished in the flames of Persepolis, but the dream of world empire never died. The Macedonian conquerors were gradually overthrown and replaced by a loose assemblage of Iranian kingdoms. The so-called Parthian Empire was a decentralised and disorderly state, but it bound together much of the sedentary Near East for about 500 years. When this empire fell in its turn, Iran got a new leader and new empire with a vengeance. The third and last pre-Islamic Iranian empire was ruled by the Sasanian dynasty from the 220s to 651 CE. Map of the Sasanian Empire. Silver coin of Ardashir I, struck at the Hamadan mint. (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Silver_coin_of_Ardashir_I,_struck_at_the_Hamadan _mint.jpg) The Last Empire of Iran. This period was arguably the heyday of ancient Iran – a time when Iranian military power nearly conquered the eastern Roman Empire, and when Persian culture reached its apogee before the coming of Islam. The founder of the Sasamian dynasty was Ardashir I who claimed descent from a mysterious ancestor called Sasan. Ardashir was the governor of Fars, a province in southern Iran, in the twilight days of the Parthian Empire. -

The 3Rd Century Ce 47

the 3rd century ce 47 Chapter FOUR THE 3rd CENTURY CE Towards the 3rd century ce, recarved private por- This is an extremely difficult, if not impossible, traits, both male and female, increased in number. task and it is very doubtful that the prices given A combination of harsh economic times and a by the Diocletian price edict are trustworthy. lack of skilled artisans led to old portraits becom- Since the prices probably reflected local condi- ing a marketable commodity. For this to happen, tions in Asia Minor, they may be completely however, the Roman view of the archetype must worthless as a price indicator for the West. The have changed. In earlier periods, the archetype results of Duncan-Jones’ analyses are, nonethe- had inspired respect, even awe, but from the time less, worth mentioning here. He identified 138 of the soldier emperors onwards, attitudes different prices for Roman statues and calculated towards it must have changed to facilitate the that the mean price was about 5000 sesterces, at recarving of portraits on a large scale. least for statues in Africa (Duncan-Jones, 1974: 78; Pekàry, 1985: 19). The highest recorded price for a statue is 66,666 sesterces, followed by 50,000 Economy and reuse and 33,320 sesterces, but these amounts indicate inflation. The lowest price he found is 2000 ses- There is abundant evidence that the Roman econ- terces, whereas about 77% of all statue prices omy at least by the middle of the 3rd century ce appear to lie between 8000 and 2000 sesterces. was going through a profound crisis from which Prices also seem to include the bases. -

Siegfried Found: Decoding the Nibelungen Period

1 Gunnar Heinsohn (Gdańsk, February 2018) SIEGFRIED FOUND: DECODING THE NIBELUNGEN PERIOD CONTENTS I Was Emperor VICTORINUS the historical model for SIEGFRIED of the Nibelungen Saga? 2 II Siegfried the Dragon Slayer and the Dragon Legion of Victorinus 12 III Time of the Nibelungen. How many migration periods occurred in the 1st millennium? Who was Clovis, first King of France? 20 IV Results 34 V Bibliography 40 Acknowledgements 41 VICTORINUS (coin portrait) 2 I Was Emperor VICTORINUS the historical model for SIEGFRIED of the Nibelungen Saga? The mythical figure of Siegfried from Xanten (Colonia Ulpia Traiana), the greatest hero of the Germanic and Nordic sagas, is based on the real Gallic emperor Victorinus (meaning “the victorious”), whose name can be translated into Siegfried (Sigurd etc.), which means “victorious” in German and the Scandinavian languages. The reign of Victorinus is conventionally dated 269-271 AD. He is one of the leaders of the so-called Gallic Empire (Imperium Galliarum; 260-274 AD), mostly known from Historia Augusta (Thayer 2018), Epitome de Caesaribus of Aurelius Victor (Banchich 2009), and the Breviarum of Eutropius (Watson 1886). The capital city of this empire was Cologne, 80 km south of Xanten. Trier and Lyon were additional administrative centers. This sub-kingdom tried to defend the western part of the Roman Empire against invaders who were taking advantage of the so-called Crisis of the Third Century, which mysteriously lasted exactly 50 years (234 to 284 AD). Yet, the Gallic Empire also had separatist tendencies and sought to become independent from Rome. The bold claim of Victorinus = Siegfried was put forward, in 1841, by A. -

Anglo-Saxons

Anglo-Saxons Plated disc brooch Kent, England Late 6th or early 7th century AD Visit resource for teachers Key Stage 2 Anglo-Saxons Contents Before your visit Background information Resources Gallery information Preliminary activities During your visit Gallery activities: introduction for teachers Gallery activities: briefings for adult helpers Gallery activity: The Franks Casket Gallery activity: Personal adornment Gallery activity: Design and decoration Gallery activity: Anglo-Saxon jobs Gallery activity: Material matters After your visit Follow-up activities Anglo-Saxons Before your visit Anglo-Saxons Before your visit Background information The end of Roman Britain The Roman legions began to be withdrawn from Britain to protect other areas of the empire from invasion by peoples living on the edge of the empire at the end of the fourth century AD. Around AD 407 Constantine III, a claimant for the imperial throne based in Britain, led the troops from Britain to Gaul in an attempt to secure control of the Western Roman Empire. He failed and was killed in Gaul in AD 411. This left the Saxon Shore forts, which had been built by the Romans to protect the coast from attacks by raiding Saxons, virtually empty and the coast of Britain open to attack. In AD 410 there was a devastating raid on the undefended coasts of Britain and Gaul by Saxons raiders. Imperial governance in Britain collapsed and although aspects of Roman Britain continued after AD 410, Britain was no longer part of the Roman empire and saw increased settlement by Germanic people, particularly in the northern and eastern regions of England. -

![World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [And Student Guide]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1845/world-history-part-1-teachers-guide-and-student-guide-2081845.webp)

World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [And Student Guide]

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 462 784 EC 308 847 AUTHOR Schaap, Eileen, Ed.; Fresen, Sue, Ed. TITLE World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [and Student Guide]. Parallel Alternative Strategies for Students (PASS). INSTITUTION Leon County Schools, Tallahassee, FL. Exceptibnal Student Education. SPONS AGENCY Florida State Dept. of Education, Tallahassee. Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 841p.; Course No. 2109310. Part of the Curriculum Improvement Project funded under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Part B. AVAILABLE FROM Florida State Dept. of Education, Div. of Public Schools and Community Education, Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services, Turlington Bldg., Room 628, 325 West Gaines St., Tallahassee, FL 32399-0400. Tel: 850-488-1879; Fax: 850-487-2679; e-mail: cicbisca.mail.doe.state.fl.us; Web site: http://www.leon.k12.fl.us/public/pass. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom - Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF05/PC34 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Accommodations (Disabilities); *Academic Standards; Curriculum; *Disabilities; Educational Strategies; Enrichment Activities; European History; Greek Civilization; Inclusive Schools; Instructional Materials; Latin American History; Non Western Civilization; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Teaching Guides; *Teaching Methods; Textbooks; Units of Study; World Affairs; *World History IDENTIFIERS *Florida ABSTRACT This teacher's guide and student guide unit contains supplemental readings, activities, -

THE PTOLEMIES and the 3Rd CENTURY B.C.E. CERAMIC ASSEMBLAGE Melanie Godsey a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty at the University O

THE PTOLEMIES AND THE 3rd CENTURY B.C.E. CERAMIC ASSEMBLAGE Melanie Godsey A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Classics. Chapel Hill 2017 Approved by: Jennifer Gates-Foster Sheila Dillon Donald Haggis © 2017 Melanie Godsey ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Melanie Godsey: The Ptolemies and the 3rd Century B.C.E. Ceramic Assemblage (Under the direction of Jennifer Gates-Foster) The Ptolemaic political, military, and economic interests in the 3rd century B.C.E. Aegean and Greek mainland fostered cultural exchange. I examine the ceramic evidence from two sites to assess the network of interaction and its impact on the function and production of Hellenistic pottery types. The ceramic assemblage from Eretria, a city with a historically Greek affiliation, will serve as a point of comparison for the evidence from Koroni, a Ptolemaic site in Attika. The ceramic assemblage from Koroni tells us three things: 1) the fine ware indicates that the Ptolemies had already begun to be involved in what will become the Hellenistic koine, 2) Koroni was not directly linked with Athens, which throws into question the function of the site, and 3) the Ptolemaic intervention in and then withdrawal from Attika and the Aegean was one reason behind the fluctuation in the market for Attic black gloss pottery. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................... -

Download PDF Datastream

A Dividing Sea The Adriatic World from the Fourth to the First Centuries BC By Keith Robert Fairbank, Jr. B.A. Brigham Young University, 2010 M.A. Brigham Young University, 2012 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program in Ancient History at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2018 © Copyright 2018 by Keith R. Fairbank, Jr. This dissertation by Keith R. Fairbank, Jr. is accepted in its present form by the Program in Ancient History as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date _______________ ____________________________________ Graham Oliver, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date _______________ ____________________________________ Peter van Dommelen, Reader Date _______________ ____________________________________ Lisa Mignone, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date _______________ ____________________________________ Andrew G. Campbell, Dean of the Graduate School iii CURRICULUM VITAE Keith Robert Fairbank, Jr. hails from the great states of New York and Montana. He grew up feeding cattle under the Big Sky, serving as senior class president and continuing on to Brigham Young University in Utah for his BA in Humanities and Classics (2010). Keith worked as a volunteer missionary for two years in Brazil, where he learned Portuguese (2004–2006). Keith furthered his education at Brigham Young University, earning an MA in Classics (2012). While there he developed a curriculum for accelerated first year Latin focused on competency- based learning. He matriculated at Brown University in fall 2012 in the Program in Ancient History. While at Brown, Keith published an appendix in The Landmark Caesar. He also co- directed a Mellon Graduate Student Workshop on colonial entanglements. -

Excavating the Roman Peasant by Kim Bowes, Mariaelena Ghisleni, Cam Grey, and Emanuele Vaccaro

ITALY Excavating the Roman Peasant BY KIM BOWES, MARIAELENA GHISLENI, CAM GREY, AND EMANUELE VACCARO e view the roman world through the rich. The humble farmsteads of the rural poor—less beautiful eyes of the wealthy—the lettered elite to look at, but arguably more critical to an understanding of who penned ancient history and litera- Roman society—have been for the most part ignored. There ture, and the ruling classes whose mon- exists no real archaeology of these lower classes, and thus our ies built Roman cities and monuments. understanding of their homes and farms, their diet and agri- WThe poor are nearly invisible to us, their textual and material cultural methods, and even their relationship with their land- traces ephemeral, in many cases nonexistent. This is particu- scapes is extremely limited. larly true of the rural poor: by some estimates the rural poor We began the Roman Peasant Project to try to answer constituted some 90% of the overall Roman population, and some of these questions. The result of a collaboration between yet their textual traces are limited to a handful of laws, asides in four young archaeologists at the University of Pennsylvania, agricultural handbooks, and some images. The richest poten- University of Cambridge, and the Università di Siena/Grosseto, tial source for these persons is archaeological evidence, but the Project constitutes the first organized attempt to excavate Roman archaeology has been largely disinterested. With some the houses and farms of peasants living between the 2nd cen- few exceptions, archaeologists have principally excavated the tury BC and the 6th century AD. -

IV in Ravenna-Classe, Lower-Class Apartments in the Harbor Area of The

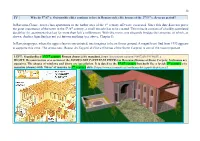

38 IV Why do 5th/6th c. Ostrogothic elites continue to live in Roman-style elite houses of the 2nd/3rd c. Severan period? In Ravenna-Classe, lower-class apartments in the harbor area of the 1st century AD were excavated. Since this date does not prove the great importance of the town in the 5th/6th century, a small miracle has to be created. This miracle consists of a boldly postulated durability for apartments that last for more than half a millennium. With this move, one elegantly bridges the centuries, of which, as shown, Andrea Agnellus has not yet known anything (see above, Chapter I). In Ravenna proper, where the upper class is concentrated, one imagines to be on firmer ground. A magnificent find from 1993 appears to supports this view. The aristocratic Domus dei Tappeti di Pietra (Domus of the Stone Carpets) is one of the most important LEFT: Standardized 1st/2nd century Roman domus (city mansion). [https://pl.pinterest.com/pin/91057223699970657/.] RIGHT: Reconstruction of a section of the DOMUS DEI TAPPETI DI PIETRA in Ravenna (Domus of Stone Carpets; bedrooms are upstairs). The shapes of windows and doors are speculation. It is dated to the 5th/6th century but built like a lavish 2nd century city mansion (domus) with 700 m2 of mosaics in 2nd century style. [https://www.ravennantica.it/en/domus-dei-tappeti-di-pietra-ra/.] 39 Italian archaeological sites discovered in recent decades. Located inside the eighteenth-century Church of Santa Eufemia, in a vast underground environment located about 3 meters below street level, it consists of 14 rooms paved with polychrome mosaics and marble belonging to a private building of the fifth-sixth century. -

And the Material Culture of the Late 3Rd Century

The theory of ‘Limesfall’ and the material culture of the late 3rd century By Stijn Heeren Keywords: Late Roman period / fall of the Limes / Lower Rhine / Obergermanisch-Raeti- scher limes / Niederbieber horizon / pottery / brooches Schlagwörter: spätrömische Zeit / Limesfall / Niederrhein / Obergermanisch-Raetischer Limes / Niederbieber-Horizont / Keramik / Fibeln Mots-clés : époque romaine tardive / chute du limes / Bas-Rhin / Obergermanisch-Raeti- scher limes / horizon Niederbieber / céramique / fibules Introduction In many historical and archaeological studies concerning the decline of Roman power in the 3rd century, the ‘Limesfall’ is addressed, either explicitly or implicitly. With the term ‘Limesfall’ the destruction of limes forts by barbarian raiders between AD 259/260 and 275 and the subsequent abandonment of settlements in the hinterland of the limes is meant. The traditional opinion is that most of the forts and cities were never inhabited again. This idea has shaped the basic chronology of provincial-Roman archaeology: the transition of the Middle to the Late Roman period is set at ca. 260 and many items of material culture in the so-called Niederbieber horizon are dated to the period 190−260. New archaeological analysis shows that this presentation of past events is an oversimpli- fication: for several stretches of the limes there is no proof for destruction and subsequent abandonment at all, and evidence to the contrary, a continued occupation of several cas- tella, is available. This has far-reaching consequences for the chronology of the material culture of the late 3rd century and our dating of the Middle to Late Roman transition. In this article it will be argued that a ‘Limesfall’ never took place along the Lower Rhine and only partially at the Obergermanisch-Raetische limes. -

Roman Settlements and the "Crisis" of the 3Rd Century AD Ager Aguntinus

Roman Settlements and the "Crisis" of the 3rd Century AD Ager Aguntinus Historisch-archäologische Forschungen Herausgegeben von Martin Auer und Harald Stadler Universität Innsbruck ATRIUM - Zentrum für Alte Kulturen Institut für Archäologien Band 4 2021 Harrassowitz Verlag · Wiesbaden Martin Auer and Christoph Hinker (Eds.) Roman Settlements and the "Crisis" of the 3rd Century AD 2021 Harrassowitz Verlag · Wiesbaden Printed with support of the Austrian Archaeological Institute of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, the University of Innsbruck (Faculty of Philosophy and History, Research Area “Cultural Encounters – Cul- tural Conflicts”) and the Curator ium pro Agunto. reviewed by: Christian Gugl, Manfred Hainzmann, Jana Horvat, Janka Istenič, Susanne Lamm, Manfred Lehner, Eliz- abeth Murphy, Salvatore Ortisi, Ivana Ožanić Roguljić, Kai Ruffing, Florian Schimmer, Eleni Schindler- Kaudelka, Alexander Sokolicek, Veronika Sossau and Eugenio Tamborrino. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über https://dnb.de/ abrufbar. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the internet at https://dnb.de/. For further information about our publishing program consult our website https://www.harrassowitz-verlag.de/ © Otto