The Sources for Rome's Wars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sasanian Twin Pillar Ossuaries at Shoush Village, Kohgiloyeh Va Boyer Ahmad (Iran)

IranicaAntiqua, vol. L, 2015 doi: 10.2143/IA.50.0.3053525 DO GUR-E DOPA: THE SASANIAN TWIN PILLAR OSSUARIES AT SHOUSH VILLAGE, KOHGILOYEH VA BOYER AHMAD (IRAN) BY Mahdokht FARJAMIRAD (Ghent University) Abstract: The pillar ossuary is a unique but a less known type of Sasanian bone receptacle that has mainly been reported from Fars. This article introduces newly discovered twin pillar ossuaries south of Basht, in southern Kohgiloyeh va Boyer Ahmad Province. During the Sasanian period this region was situated in northern Pārs that is still one of the poorly known areas in Iranian archaeology. Keywords: Kohgiloyeh va Boyer Ahmad, northern Pārs, pillar ossuary, astodan, Zoroastrianism, Sasanian, bone receptacle. Introduction Pillar ossuaries were frequently reported from the area of Istakhr as well as northern Sasanian Pārs. Pārs province was located in the southern quadrant of the Sasanian Empire between Kirman in the east, Khuzistan in the west, and Pahlaw (Isfahan) in the north (Miri 2012: 25). Do-Gur-e Dopa is one of a few examples of pillar astodans in northern Pārs that, based on the geographical administrative division of the Sasanian period, was likely part of the districts of Shapur Xwarrah (Istakhri: 102) or Veh-Az-Amid-Kavād (Gyselen 1989: 72 & 98). In early Islamic sources this area was on the way from Shiraz to Arrajān (near modern Behbahan) (Gaube 1986; Eqtedari 1989; Miri 2012: 131). In the modern geographi- cal division Do-Gur-e Dopa is located in the south of Kohgiloyeh va Boyer Ahmad province. The aim of this paper is to introduce the twin pillar ossuaries of Do Gur-e Dopa as one of the few known Sasanian archaeological remains in this region, which is indeed one of the least archaeologically known regions in the Zagros Mountains. -

RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian's “Great

ABSTRACT RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy. (Under the direction of Prof. S. Thomas Parker) In the year 303, the Roman Emperor Diocletian and the other members of the Tetrarchy launched a series of persecutions against Christians that is remembered as the most severe, widespread, and systematic persecution in the Church’s history. Around that time, the Tetrarchy also issued a rescript to the Pronconsul of Africa ordering similar persecutory actions against a religious group known as the Manichaeans. At first glance, the Tetrarchy’s actions appear to be the result of tensions between traditional classical paganism and religious groups that were not part of that system. However, when the status of Jewish populations in the Empire is examined, it becomes apparent that the Tetrarchy only persecuted Christians and Manichaeans. This thesis explores the relationship between the Tetrarchy and each of these three minority groups as it attempts to understand the Tetrarchy’s policies towards minority religions. In doing so, this thesis will discuss the relationship between the Roman state and minority religious groups in the era just before the Empire’s formal conversion to Christianity. It is only around certain moments in the various religions’ relationships with the state that the Tetrarchs order violence. Consequently, I argue that violence towards minority religions was a means by which the Roman state policed boundaries around its conceptions of Roman identity. © Copyright 2016 Carl Ross Rice All Rights Reserved Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy by Carl Ross Rice A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2016 APPROVED BY: ______________________________ _______________________________ S. -

THE 3Rd CENTURY MILITARY EQUIPMENT in SOUTH-WESTERN SLOVENIA

The Roman army between the Alps and the Adriatic, Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 31 / Studia Alpium et Adriae I, 2016, 99–120 THE 3rd CENTURY MILITARY EQUIPMENT IN SOUTH-WESTERN SLOVENIA Jana HORVAT, Beatriče ŽBONA TRKMAN † Abstract The significant unrest that characterized the final decades of therd 3 century lead to intensive control over communication routes and to the fortification of the most important settlements in the south-eastern Alpine area. Two assemblages originat- ing from south-western Slovenia are presented to achieve a better understanding of the period. The hoard from Prelovce near Malovše dated to the second half of the 3rd century and consisted of horse harness decoration, a military belt, and a combat knife. The hoard may suggest army movement or military control of the main road. A group of sixteen graves was found in Javor near Dolnji Zemon, and the majority of them originate from the second half of the 3rd century. The grave goods in two graves indicate a military affiliation of the deceased; a female grave containing silver jewellery corroborates the special social position of the whole group. It is possible that a military detachment was stationed at Javor near Dolnji Zemon, and controlled the road from Tarsatica to the Postojna basin. Keywords: South-western Slovenia, second half of the 3rd century, Prelovce near Malovše, Javor near Dolnji Zemon, hoards, graves, horse harness decoration, combat knives, jewellery INTRODUCTION dated in the 320s.3 The fortress at Nauportus (Vrhnika) might date at the end of the 3rd century.4 On the basis of The final decades of the 3rd century are character- coin finds it is presumed that the principia in Tarsatica ized by increasing control over communication routes were constructed at the end of the 270s or during the and by the fortification of the most important settle- 280s.5 The short-lived Pasjak fortress on the Aquileia– ments in the south-eastern Alpine area. -

The Last Empire of Iran by Michael R.J

The Last Empire of Iran By Michael R.J. Bonner In 330 BCE, Alexander the Great destroyed the Persian imperial capital at Persepolis. This was the end of the world’s first great international empire. The ancient imperial traditions of the Near East had culminated in the rule of the Persian king Cyrus the Great. He and his successors united nearly all the civilised people of western Eurasia into a single state stretching, at its height, from Egypt to India. This state perished in the flames of Persepolis, but the dream of world empire never died. The Macedonian conquerors were gradually overthrown and replaced by a loose assemblage of Iranian kingdoms. The so-called Parthian Empire was a decentralised and disorderly state, but it bound together much of the sedentary Near East for about 500 years. When this empire fell in its turn, Iran got a new leader and new empire with a vengeance. The third and last pre-Islamic Iranian empire was ruled by the Sasanian dynasty from the 220s to 651 CE. Map of the Sasanian Empire. Silver coin of Ardashir I, struck at the Hamadan mint. (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Silver_coin_of_Ardashir_I,_struck_at_the_Hamadan _mint.jpg) The Last Empire of Iran. This period was arguably the heyday of ancient Iran – a time when Iranian military power nearly conquered the eastern Roman Empire, and when Persian culture reached its apogee before the coming of Islam. The founder of the Sasamian dynasty was Ardashir I who claimed descent from a mysterious ancestor called Sasan. Ardashir was the governor of Fars, a province in southern Iran, in the twilight days of the Parthian Empire. -

Lecture 27 Sasanian Empire

4/12/2012 Lecture 27 Sasanian Empire HIST 213 Spring 2012 Sasanian Empire (224-651 CE) Successors of the Achaemenids 224 CE Ardashir I • a descendant of Sasan – gave his name to the new Sasanian dynasty, • defeated the Parthians • The Sasanians saw themselves as the successors of the Achaemenid Persians. 1 4/12/2012 Shapur I (r. 241–72 CE) • One of the most energetic and able Sasanian rulers • the central government was strengthened • the coinage was reformed • Zoroastrianism was made the state religion • The expansion of Sasanian power in the west brought conflict with Rome Shapur I the Conqueror • conquers Bactria and Kushan in east • led several campaigns against Rome in west Penetrating deep into Eastern-Roman territory • conquered Antiochia (253 or 256) Defeated the Roman emperors: • Gordian III (238–244) • Philip the Arab (244–249) • Valerian (253–260) – 259 Valerian taken into captivity after the Battle of Edessa – disgrace for the Romans • Shapur I celebrated his victory by carving the impressive rock reliefs in Naqsh-e Rostam. Rome defeated in battle Relief of Shapur I at Naqsh-e Rostam, showing the two defeated Roman Emperors, Valerian and Philip the Arab 2 4/12/2012 Terry Jones, Barbarians (BBC 2006) clip 1=9:00 to end clip 2 start - … • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t_WqUbp RChU&feature=related • http://www.youtube.com/watch?NR=1&featu re=endscreen&v=QxS6V3lc6vM Shapur I Religiously Tolerant Intensive development plans • founded many cities, some settled in part by Roman emigrants. – included Christians who could exercise their faith freely under Sasanian rule • Shapur I particularly favored Manichaeism – He protected Mani and sent many Manichaean missionaries abroad • Shapur I befriends Babylonian rabbi Shmuel – This friendship was advantageous for the Jewish community and gave them a respite from the oppressive laws enacted against them. -

The Gallic Empire (260-274): Rome Breaks Apart

The Gallic Empire (260-274): Rome Breaks Apart Six Silver Coins Collection An empire fractures Roman chariots All coins in each set are protected in an archival capsule and beautifully displayed in a mahogany-like box. The box set is accompanied with a story card, certificate of authenticity, and a black gift box. By the middle of the third century, the Roman Empire began to show signs of collapse. A parade of emperors took the throne, mostly from the ranks of the military. Years of civil war and open revolt led to an erosion of territory. In the year 260, in a battle on the Eastern front, the emperor Valerian was taken prisoner by the hated Persians. He died in captivity, and his corpse was stuffed and hung on the wall of the palace of the Persian king. Valerian’s capture threw the already-fractured empire into complete disarray. His son and co-emperor, Gallienus, was unable to quell the unrest. Charismatic generals sought to consolidate their own power, but none was as powerful, or as ambitious, as Postumus. Born in an outpost of the Empire, of common stock, Postumus rose swiftly through the ranks, eventually commanding Roman forces “among the Celts”—a territory that included modern-day France, Belgium, Holland, and England. In the aftermath of Valerian’s abduction in 260, his soldiers proclaimed Postumus emperor. Thus was born the so-called Gallic Empire. After nine years of relative peace and prosperity, Postumus was murdered by his own troops, and the Gallic Empire, which had depended on the force of his personality, began to crumble. -

EASTERN CENTRAL ASIA the Early History of Central Asia Is Gleaned

CHAPTER FOUR EASTERN CENTRAL ASIA KASHGAR TO KHOTAN I. INTRODUCTION The early history of Central Asia is gleaned primarily from three major sources: the Chinese historical writings, usually governmental records or the diaries of the Bud dhist pilgrims; documents written in Kharosthl-an Indian script also adopted by the Kushans-(and some in an Iranian dialect using technical terms in Sanskrit and Prakrit) that reveal aspects of the local life; and later Muslim, Arab, Persian, and Turkish writings. 1 From these is painstakingly emerging a tentative history that pro vides a framework, admittedly still fragmentary, for beginning to understand this vital area and prime player between China, India, and the West during the period from the 1st to 5th century A.D. Previously, we have encountered the Hsiung-nu, particularly the northern branch, who dominated eastern Central Asia during much of the Han period (206 B.C.-220 A.D.), and the Yiieh-chih, a branch of which migrated from Kansu to northwest India and formed the powerful and influential Kushan empire of ca. lst-3rd century A.D. By ca. mid-3rd century the unified Kushan empire had ceased and the main line of kings from Kani~ka had ended. Another branch (the Eastern Kushans) ruled in Gandhara and the Indus Valley, and the northernpart of the former Kushan em pire came under the rule of Sasanian governors. However, after the death of the Sasanian ruler Shapur II in 379, the so-called Kidarites, named from Kidara, the founder of this "new" or Little Kushan Dynasty (known as the Little Yiieh-chih by the Chinese), appear to have unified the area north and south of the Hindu Kush between around 380-430 (likely before 410). -

Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq

OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES General Editors Gillian Clark Andrew Louth THE OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES series includes scholarly volumes on the thought and history of the early Christian centuries. Covering a wide range of Greek, Latin, and Oriental sources, the books are of interest to theologians, ancient historians, and specialists in the classical and Jewish worlds. Titles in the series include: Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and the Transformation of Divine Simplicity Andrew Radde-Gallwitz (2009) The Asceticism of Isaac of Nineveh Patrik Hagman (2010) Palladius of Helenopolis The Origenist Advocate Demetrios S. Katos (2011) Origen and Scripture The Contours of the Exegetical Life Peter Martens (2012) Activity and Participation in Late Antique and Early Christian Thought Torstein Theodor Tollefsen (2012) Irenaeus of Lyons and the Theology of the Holy Spirit Anthony Briggman (2012) Apophasis and Pseudonymity in Dionysius the Areopagite “No Longer I” Charles M. Stang (2012) Memory in Augustine’s Theological Anthropology Paige E. Hochschild (2012) Orosius and the Rhetoric of History Peter Van Nuffelen (2012) Drama of the Divine Economy Creator and Creation in Early Christian Theology and Piety Paul M. Blowers (2012) Embodiment and Virtue in Gregory of Nyssa Hans Boersma (2013) The Chronicle of Seert Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq PHILIP WOOD 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries # Philip Wood 2013 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2013 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. -

The Migration of Syrian and Palestinian Populations in the 7Th Century: Movement of Individuals and Groups in the Mediterranean

Chapter 10 The Migration of Syrian and Palestinian Populations in the 7th Century: Movement of Individuals and Groups in the Mediterranean Panagiotis Theodoropoulos In 602, the Byzantine emperor Maurice was dethroned and executed in a mili- tary coup, leading to the takeover of Phokas. In response to that, the Sasanian Great King Khosrow ii (590–628), who had been helped by Maurice in 591 to regain his throne from the usurper Bahram, launched a war of retribution against Byzantium. In 604 taking advantage of the revolt of the patrikios Nars- es against Phokas, he captured the city of Dara. By 609, the Persians had com- pleted the conquest of Byzantine Mesopotamia with the capitulation of Edes- sa.1 A year earlier, in 608, the Exarch of Carthage Herakleios the Elder rose in revolt against Phokas. His nephew Niketas campaigned against Egypt while his son, also named Herakleios, led a fleet against Constantinople. Herakleios managed to enter the city and kill Phokas. He was crowned emperor on Octo- ber 5, 610.2 Ironically, three days later on October 8, 610, Antioch, the greatest city of the Orient, surrendered to the Persians who took full advantage of the Byzantine civil strife.3 A week later Apameia, another great city in North Syria, came to terms with the Persians. Emesa fell in 611. Despite two Byzantine counter at- tacks, one led by Niketas in 611 and another led by Herakleios himself in 613, the Persian advance seemed unstoppable. Damascus surrendered in 613 and a year later Caesarea and all other coastal towns of Palestine fell as well. -

Innovamass 240S/241S Manual

InnovaMass 240S/241S Instruction Manual Table of Contents 240/241 Series Vortex Volumetric and Mass Flow Meters Models: 240-V, VT, VTP, LP / 241-V, VT, VTP, LP, Cryogenic Instruction Manual Document Number IM-240 Revision: Q 6/20 IM-240 0-1 Table of Contents InnovaMass 240S/241S Instruction Manual GLOBAL SUPPORT LOCATIONS: WE ARE HERE TO HELP! CORPORATE HEADQUARTERS 5 Harris Court, Building L Monterey, CA 93940 Phone (831) 373-0200 (800) 866-0200 Fax (831) 373-4402 www.sierrainstruments.com EUROPE HEADQUARTERS Bijlmansweid 2 1934RE Egmond aan den Hoef The Netherlands Phone +31 72 5071400 Fax +31 72 5071401 ASIA HEADQUARTERS Second Floor Building 5 Senpu Industrial park 25 Hangdu Road Hangtou Town Pu Dong New District Shanghai, P.R. China Post Code 201316 Phone: 8621 5879 8521 Fax: 8621 5879 8586 Important Customer Notice for Oxygen Service Unless you have specifically ordered Sierra’s optional O2 cleaning, this flow meter may not be fit for oxygen service. Some models can only be properly cleaned during the manufacturing process. Sierra Instruments, Inc. is not liable for any damage or personal injury, whatsoever, resulting from the use of Sierra Instruments standard mass flow meters for oxygen gas. Specific Conditions of Use(ATEX/IECEx) Contact Manufacturer regarding Flame path information. Clean with a damp cloth to avoid any build-up of electrostatic charge. The model 240S and 241S Multivariable Mass Vortex Flowmeters standard temperature option (ST) process temperature range is -40°C to 260°C. The high temperature option (HT) process temperature range is -40°C up to +400°C. -

From Small States to Universalism in the Pre-Islamic Near East

REVOLUTIONIZING REVOLUTIONIZING Mark Altaweel and Andrea Squitieri and Andrea Mark Altaweel From Small States to Universalism in the Pre-Islamic Near East This book investigates the long-term continuity of large-scale states and empires, and its effect on the Near East’s social fabric, including the fundamental changes that occurred to major social institutions. Its geographical coverage spans, from east to west, modern- day Libya and Egypt to Central Asia, and from north to south, Anatolia to southern Arabia, incorporating modern-day Oman and Yemen. Its temporal coverage spans from the late eighth century BCE to the seventh century CE during the rise of Islam and collapse of the Sasanian Empire. The authors argue that the persistence of large states and empires starting in the eighth/ seventh centuries BCE, which continued for many centuries, led to new socio-political structures and institutions emerging in the Near East. The primary processes that enabled this emergence were large-scale and long-distance movements, or population migrations. These patterns of social developments are analysed under different aspects: settlement patterns, urban structure, material culture, trade, governance, language spread and religion, all pointing at population movement as the main catalyst for social change. This book’s argument Mark Altaweel is framed within a larger theoretical framework termed as ‘universalism’, a theory that explains WORLD A many of the social transformations that happened to societies in the Near East, starting from Andrea Squitieri the Neo-Assyrian period and continuing for centuries. Among other infl uences, the effects of these transformations are today manifested in modern languages, concepts of government, universal religions and monetized and globalized economies. -

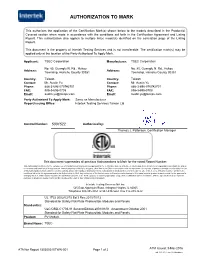

Authorization to Mark

AUTHORIZATION TO MARK This authorizes the application of the Certification Mark(s) shown below to the models described in the Product(s) Covered section when made in accordance with the conditions set forth in the Certification Agreement and Listing Report. This authorization also applies to multiple listee model(s) identified on the correlation page of the Listing Report. This document is the property of Intertek Testing Services and is not transferable. The certification mark(s) may be applied only at the location of the Party Authorized To Apply Mark. Applicant: TSEC Corporation Manufacturer: TSEC Corporation No. 85, Guangfu N. Rd., Hukou No. 85, Guangfu N. Rd., Hukou Address: Address: Township, Hsinchu County 30351 Township, Hsinchu County 30351 Country: Taiwan Country: Taiwan Contact: Mr. Austin Yu Contact: Mr. Austin Yu Phone: 886-3-696-0707#2701 Phone: 886-3-696-0707#2701 FAX: 886-3-696-0708 FAX: 886-3-696-0708 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Party Authorized To Apply Mark: Same as Manufacturer Report Issuing Office: Intertek Testing Services Taiwan Ltd. Control Number: 5001522 Authorized by: Thomas J. Patterson, Certification Manager This document supersedes all previous Authorizations to Mark for the noted Report Number. This Authorization to Mark is for the exclusive use of Intertek's Client and is provided pursuant to the Certification agreement between Intertek and its Client. Intertek's responsibility and liability are limited to the terms and conditions of the agreement. Intertek assumes no liability to any party, other than to the Client in accordance with the agreement, for any loss, expense or damage occasioned by the use of this Authorization to Mark.