Rob Ninkovich, Linebacker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Campus Houses Robbed Physicist Analyzes Ice Skating Buddhist Monk

THE INDEPENDENT TO UNCOVER NEWSPAPER SERVING THE TRUTH NOTRE DAME AND AND REPORT SAINT Mary’s IT ACCURATELY VOLUME 47, ISSUE 56 | THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 21, 2013 | NDSMCOBSERVER.COM Students address sexual violence Off- Town hall meeting examines survey results, barriers to sexual assault reporting campus By MEG HANDELMAN alert emails and to think sex- News Writer ual violence does not occur at Notre Dame, but the right houses Student government host- thing to do is almost never ed a town hall discussion on easy, Daegele said. sexual violence Wednesday to “Silence: it surrounds every open up the on-campus dis- situation of sexual violence,” robbed cussion and instigate activism she said. “It keeps survivors in students. from telling their stories. It Observer Staff Report Monica Daegele, student makes us pretend that nothing government’s gender issues is wrong. It propagates sexual An email sent Wednesday director, said Notre Dame violence as it alienates those from Notre Dame’s Off Campus students dedicate themselves who have experienced it. Council notified students of to various causes to make the “It is the invisible force field a burglary and attempted world a better place, but they that smothers the sexual vio- burglary that took place last have failed to connect this ef- lence movement.” weekend. fort to sexual assault. Student body president A burglary to a student resi- “When we do discuss sexual Nancy Joyce shared statis- dence took place Sunday be- violence or actively work to put tics from a survey given to tween 12 a.m. and 9 a.m. on an end to it, it feels as though Notre Dame students in 2012. -

Congressional Record—Senate S13621

November 2, 1999 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð SENATE S13621 message from the Chicago Bears. Many ex- with him. You could tell he was very The last point I will make is, toward ecutives knew what it said before they read genuine.'' the end of his life when announcing he it: Walter Payton, one of the best ever to Bears fans in Chicago felt the same way, faced this fatal illness, he made a plea which is why reaction to his death was swift play running back, had died. across America to take organ donation For the past several days it has been ru- and universal. mored that Payton had taken a turn for the ``He to me is ranked with Joe DiMaggio in seriously. He needed a liver transplant worse, so the league was braced for the news. baseballÐhe was the epitome of class,'' said at one point in his recuperation. It Still, the announcement that Payton had Hank Oettinger, a native of Chicago who was could have made a difference. It did not succumbed to bile-duct cancer at 45 rocked watching coverage of Payton's death at a bar happen. and deeply saddened the world of profes- on the city's North Side. ``The man was such I do not know the medical details as sional football. a gentleman, and he would show it on the to his passing, but Walter Payton's ``His attitude for life, you wanted to be football field.'' message in his final months is one we around him,'' said Mike Singletary, a close Several fans broke down crying yesterday as they called into Chicago television sports should take to heart as we remember friend who played with Payton from 1981 to him, not just from those fuzzy clips of 1987 on the Bears. -

"The Olympics Don't Take American Express"

“…..and the Olympics didn’t take American Express” Chapter One: How ‘Bout Those Cowboys I inherited a predisposition for pain from my father, Ron, a born and raised Buffalonian with a self- mutilating love for the Buffalo Bills. As a young boy, he kept scrap books of the All American Football Conference’s original Bills franchise. In the 1950s, when the AAFC became the National Football League and took only the Cleveland Browns, San Francisco 49ers, and Baltimore Colts with it, my father held out for his team. In 1959, when my father moved the family across the country to San Jose, California, Ralph Wilson restarted the franchise and brought Bills’ fans dreams to life. In 1960, during the Bills’ inaugural season, my father resumed his role as diehard fan, and I joined the ranks. It’s all my father’s fault. My father was the one who tapped his childhood buddy Larry Felser, a writer for the Buffalo Evening News, for tickets. My father was the one who took me to Frank Youell Field every year to watch the Bills play the Oakland Raiders, compliments of Larry. By the time I had celebrated Cookie Gilcrest’s yardage gains, cheered Joe Ferguson’s arm, marveled over a kid called Juice, adapted to Jim Kelly’s K-Gun offense, got shocked by Thurman Thomas’ receptions, felt the thrill of victory with Kemp and Golden Wheels Dubenion, and suffered the agony of defeat through four straight Super Bowls, I was a diehard Bills fan. Along with an entourage of up to 30 family and friends, I witnessed every Super Bowl loss. -

Nfl) Retirement System

S. HRG. 110–1177 OVERSIGHT OF THE NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE (NFL) RETIREMENT SYSTEM HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SEPTEMBER 18, 2007 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 76–327 PDF WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:26 Oct 23, 2012 Jkt 075679 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\DOCS\76327.TXT JACKIE SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii, Chairman JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia TED STEVENS, Alaska, Vice Chairman JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota TRENT LOTT, Mississippi BARBARA BOXER, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas BILL NELSON, Florida OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine MARIA CANTWELL, Washington GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey JOHN ENSIGN, Nevada MARK PRYOR, Arkansas JOHN E. SUNUNU, New Hampshire THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware JIM DEMINT, South Carolina CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri DAVID VITTER, Louisiana AMY KLOBUCHAR, Minnesota JOHN THUNE, South Dakota MARGARET L. CUMMISKY, Democratic Staff Director and Chief Counsel LILA HARPER HELMS, Democratic Deputy Staff Director and Policy Director CHRISTINE D. KURTH, Republican Staff Director and General Counsel PAUL NAGLE, Republican Chief Counsel (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:26 Oct 23, 2012 Jkt 075679 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\GPO\DOCS\76327.TXT JACKIE C O N T E N T S Page Hearing held on September 18, 2007 .................................................................... -

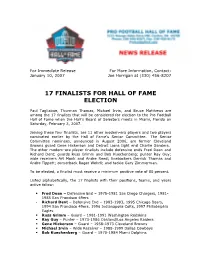

17 Finalists for Hall of Fame Election

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact: January 10, 2007 Joe Horrigan at (330) 456-8207 17 FINALISTS FOR HALL OF FAME ELECTION Paul Tagliabue, Thurman Thomas, Michael Irvin, and Bruce Matthews are among the 17 finalists that will be considered for election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame when the Hall’s Board of Selectors meets in Miami, Florida on Saturday, February 3, 2007. Joining these four finalists, are 11 other modern-era players and two players nominated earlier by the Hall of Fame’s Senior Committee. The Senior Committee nominees, announced in August 2006, are former Cleveland Browns guard Gene Hickerson and Detroit Lions tight end Charlie Sanders. The other modern-era player finalists include defensive ends Fred Dean and Richard Dent; guards Russ Grimm and Bob Kuechenberg; punter Ray Guy; wide receivers Art Monk and Andre Reed; linebackers Derrick Thomas and Andre Tippett; cornerback Roger Wehrli; and tackle Gary Zimmerman. To be elected, a finalist must receive a minimum positive vote of 80 percent. Listed alphabetically, the 17 finalists with their positions, teams, and years active follow: Fred Dean – Defensive End – 1975-1981 San Diego Chargers, 1981- 1985 San Francisco 49ers Richard Dent – Defensive End – 1983-1993, 1995 Chicago Bears, 1994 San Francisco 49ers, 1996 Indianapolis Colts, 1997 Philadelphia Eagles Russ Grimm – Guard – 1981-1991 Washington Redskins Ray Guy – Punter – 1973-1986 Oakland/Los Angeles Raiders Gene Hickerson – Guard – 1958-1973 Cleveland Browns Michael Irvin – Wide Receiver – 1988-1999 -

Congressional Record—Senate S5136

S5136 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE June 5, 2008 his last 2 years, and the nominations amendment, a third on an inter- steel market. This will put our industry at a were gridlocked, and slowed down. national competitiveness amendment, serious disadvantage and likely send jobs Similarly, with President Bush the and a fourth on process gas emissions. overseas actually increasing emissions from steelmaking in non-carbon-reducing nations. first, the last 2 years were slowed There being no objection, the mate- down, and then other devices and pro- rial was ordered to be printed in the Mr. SPECTER. But there is no way cedures were employed during the last RECORD, as follows: to get 60 votes to impose cloture unless we find a way to allow Senators to 2 years of President Clinton’s adminis- SPECTER AMENDMENTS TO LIEBERMAN- tration, procedures employed by the WARNER BILL offer their amendments. Finally, I ask unanimous consent Republican caucus. As I have said on a As I stated on the Senate floor on Tuesday, that the full text of a floor statement number of occasions, I think the Re- it was my intention to offer amendments; of mine on the New England Patriots publican caucus was wrong. I said so, It is very disappointing that the Majority Leaders has opted to move to cloture on the videotaping of NFL football games be and I voted so, in support of President Boxer substitute without allowing consider- printed in the CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Clinton’s nominations. And now, I ation of amendments; as if read in full on the Senate floor. -

Miller: Debartolo's Legacy Has Far Reaching Impact on NFL - Yahoo! Sports

Miller: DeBartolo's legacy has far reaching impact on NFL - Yahoo! Sports New User? Register Sign In Help Make Y! My Homepage Mail My Y! Yahoo! Search Web Home NFL MLB NBA NHL NCAAF NCAAB NASCAR Golf UFC Boxing Soccer More ThePostGame Shop Fantasy NFL Home News Scores And Schedules Standings Stats Teams Players Transactions Injuries Odds Video Blog Picks Tickets TB Thu WAS Sun SEA Sun CAR Sun NE Sun IND Sun MIA Sun SD Sun JAC Sun ATL Sun OAK Sun NFL MIN 8:20 PM PIT 1:00 PM DET 1:00 PM CHI 1:00 PM STL 1:00 PM TEN 1:00 PM NYJ 1:00 PM CLE 1:00 PM GB 1:00 PM PHI 1:00 PM KC 4:05 PM DISCOVER YAHOO! Login NEWS FOR YOU WITH YOUR FRIENDS Learn more UNC player delivers what looks like dirty cheap shot on Duke’s top player (VIDEO) Lolo Jones’ new venture: bobsledding! Vandals use ATV’s to damage East Carolina’s Miller: DeBartolo's legacy has far reaching field, stadium impact on NFL Jay Cutler shows toughness in game, compassion for family of slain fan By Ira Miller, The Sports Xchange | The SportsXchange – 16 hours ago The NBA creates a ‘Reggie Miller rule’ in order to punish shooters attempting to kick defenders Email Recommend Tweet 4 0 3 Here's a 'suggestion' for Panther Cam Newton: Stop throwing people under the bus Preliminary ballots for the Pro Football Hall of Fame are in the Wild trick play TD accounts for year’s first bounce pass assist before hoops even start mail, and we are left to ponder whether the committee finally will Five elementary schoolers suffer concussions in enshrine the most obvious candidate on the list. -

*** Csn Announces Comprehensive 2017-18 Patriots Football Coverage ***

*** CSN ANNOUNCES COMPREHENSIVE 2017-18 PATRIOTS FOOTBALL COVERAGE *** CHARLIE WEIS & ROB NINKOVICH TO JOIN CSN’S PATS COVERAGE TEAM THIS SEASON Joining Expert Talent Team of Michael Felger, Troy Brown, Dan Koppen, Jerod Mayo, Devin McCourty, Tom E. Curran, Bert Breer, Mike Giardi, Phil Perry, & Others Network to Feature Patriots Shows EVERY SINGLE NIGHT this season Beginning at 6PM, including Pregame Live, Halftime Live, Postgame Live, Monday Night Patriots, Quick Slants, Patriots Wednesday, New England Tailgate, Football Fix, Patriots This Week, and Patriots Football Weekly BURLINGTON, MA, September 6, 2017 - The NFL season has arrived and CSN New England will once again bring viewers more New England Patriots coverage than ever before with dedicated Patriots shows every single night of the week throughout the entire season beginning at 6PM. CSN’s football coverage will feature top-notch talent and key football guests, including more Patriots players -- both current and former -- throughout the week than any other network. New to CSN’s expert talent team this season will be former Patriots Offensive Coordinator Charlie Weis and recently retired Patriots Defensive End Rob Ninkovich. CSN will bring viewers the most robust offering of coverage of their New England Patriots with fresh Patriots programming seven days a week, including: Pregame Live, Halftime Live, Postgame Live, Monday Night Patriots, Quick Slants, Patriots Wednesday, New England Tailgate, Football Fix, Patriots This Week, and Patriots FootBall Weekly. Headlining these shows will be some of the best voices in football and television, including new faces Weis and Ninkovich, joining expert returning talent Michael Felger, Troy Brown, Dan Koppen, Jerod Mayo, Devin McCourty, Tom E. -

Deflated: the Strategic Impact of the “Deflategate” Scandal on the NFL and Its Golden Boy

Volume 6 2017 www.csscjournal.org ISSN 2167-1974 Deflated: The Strategic Impact of the “Deflategate” Scandal on the NFL and its Golden Boy Michael G. Strawser Stacie Shain Alexandria Thompson Katie Vulich Crystal Simons Bellarmine University Abstract In January 2015, the Indianapolis Colts informed the National Football League of suspicion of ball deflation by the New England Patriots in a playoff game. What followed was a multi-year battle between the NFL, a “model” franchise, and one of the league’s most polarizing players, Tom Brady. This case study details what would affectionately become Deflategate through the lens of agenda setting and primarily image restoration theories and contains an analysis of the public relations process. Keywords: NFL; Deflategate; Tom Brady; New England Patriots; image restoration; agenda setting Introduction Not. Another. Scandal. Football fans across the country could almost hear those words coming from National Football League Commissioner Roger Goodell’s mouth moments after the “Deflategate” scandal broke in January 2015. Goodell and the NFL had barely recovered from the 2014 Rice video and its aftermath—which included strengthening the league’s domestic To cite this article Strawser, M. G., Shain, S., Thompson, A., Vulich, K., & Simons, C. (2017). Deflated: The strategic impact of the “Deflategate” scandal on the NFL and its golden boy. Case Studies in Strategic Communication, 6, 62-88. Available online: http://cssc.uscannenberg.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/v6art3.pdf Strawser et al. Deflated violence policy, promising to better educate its players about domestic violence, suspending Rice (who was released by the Baltimore Ravens Sept. -

Patriots Football Network

PAT RIOTS VS . BROW NS SERIES HISTORY BILL B ELICHICK IN CLEVELAND The Patriots and Browns will meet for Patri ots Head Coach Bill Belichick was the head c oach of the the 22nd time overall when the clubs Cleve land Browns for five seasons fr om 1991-95. Be lichick took square off on Su nday. over with the Browns comin g off of what was their w orst season The Patriots have won the last four in fra nchise history, a 3-13 campai gn in 1990. By 199 4, Belichick games datin g b ack to 2001. had coached the Bro wns to an 11-5 record and a pl ayoff berth. Cleveland lea ds the all-time s eries with The Browns’ 11 victo ries in 1994 are tied for the sec ond highest a 12-9 mark, i ncludin g one p ostseason sin gle-season win tot al in the history of the franchis e, and their game when th e Bill Belichick-le d Browns claime d a 20-13 victor y playo ff victory over the Patriots in the wild card round that over the Patriot s on New Year’s Day, 1995 in a Wild Card Playo ff seas on stands as th e franchise’s m ost recent play off win. In game at Clevela nd’s Municipal St adium. 1994 , the Browns all owed just 204 points – the fe west points The Patriots and Browns pla yed five times i n a si x-year spa n allow ed in the NFL th at season and t he fewest points allowed by from 1999-200 4 and then wen t three season s before the las t a def ense coached b y Belichick. -

Super Bowl XLVIII on FOX Broadcast Guide

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 PHOTOGRAPHY 2 FOX SUPER BOWL SUNDAY BROADCAST SCHEDULE 3-6 SUPER BOWL WEEK ON FOX SPORTS 1 TELECAST SCHEDULE 7-10 PRODUCTION FACTS 11-13 CAMERA DIAGRAM 14 FOX SPORTS AT SUPER BOWL XLVIII FOXSports.com 15 FOX Sports GO 16 FOX Sports Social Media 17 FOX Sports Radio 18 FOX Deportes 19-21 SUPER BOWL AUDIENCE FACTS 22-23 10 TOP-RATED PROGRAMS ON FOX 24 SUPER BOWL RATINGS & BROADCASTER HISTORY 25-26 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 27 SUPERBOWL CONFERENCE CALL HIGHLIGHTS 28-29 BROADCASTER, EXECUTIVE & PRODUCTION BIOS 30-62 MEDIA INFORMATION The Super Bowl XLVIII on FOX broadcast guide has been prepared to assist you with your coverage of the first-ever Super Bowl played outdoors in a northern locale, coming Sunday, Feb. 2, live from MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, NJ, and it is accurate as of Jan. 22, 2014. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to assist you with the latest information, photographs and interview requests as needs arise between now and game day. SUPER BOWL XLVIII ON FOX CONFERENCE CALL SCHEDULE CALL-IN NUMBERS LISTED BELOW : Thursday, Jan. 23 (1:00 PM ET) – FOX SUPER BOWL SUNDAY co-host Terry Bradshaw, analyst Michael Strahan and FOX Sports President Eric Shanks are available to answer questions about the Super Bowl XLVIII pregame show and examine the matchups. Call-in number: 719-457-2083. Replay number: 719-457-0820 Passcode: 7331580 Thursday, Jan. 23 (2:30 PM ET) – SUPER BOWL XLVIII ON FOX broadcasters Joe Buck and Troy Aikman, Super Bowl XLVIII game producer Richie Zyontz and game director Rich Russo look ahead to Super Bowl XLVIII and the network’s coverage of its seventh Super Bowl. -

NEW ENGLAND Patriots Vs. Buffalo Bills Media Schedule GAME SUMMARY NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (12-3) Vs BUFFALO BILLS (8-7) WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 24 Sunday, Dec

REGULAR SEASON WEEK 17 NEW ENGLAND patriots vs. buffalo bills Media schedule GAME SUMMARY NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (12-3) vs BUFFALO BILLS (8-7) WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 24 Sunday, Dec. 28, 2014 • Gillette Stadium (68,756) • 1:00 p.m. ET TBD Media Check-In (Ticket Office) The New England Patriots will close out the 2014 regular season when they host the Buffalo TBD Media Access at Practice Bills on Sunday. It is the fourth time in the last seven seasons and the second straight season that the Patriots will end the regular season against Buffalo. TBD Patriots Player Availability The Patriots are assured of being the top seed in the AFC playoffs as a result of the Denver (Open Locker Room) Broncos’ 37-28 loss to the Cincinnati Bengals on Monday night. It is the fifth time the Patriots TBD Bills Player TBD have earned the top seed (2003, 2007, 2010, 2011 and 2014). Conference Call The Patriots have won their last 13 home games against the Bills, including a perfect 12-0 record at Gillette Stadium. Additionally, Tom Brady is 23-2 all-time against Buffalo. Approx. 2:30 p.m. Bills Head Coach Doug Marrone The Patriots are 7-0 at home in 2014 and will attempt to finish a perfect 8-0 at Gillette Sta- Conference Call dium for the seventh time in team history. New England has finished perfect at home in 2003, 2004, 2007, 2009, 2010 and 2013. The only other teams that are undefeated at home in THURSDAY, DECEMBER 25 2014 are Denver and Green Bay.