Rob Ninkovich, Linebacker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Game Summaries:IMG.Qxd

Sunday, September 12, 2010 Green Bay Packers 27 Lincoln Financial Field Philadelphia Eagles 20 Clad in their Kelly green uniforms in honor of the 1960 NFL cham- 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Pts pions, the Philadelphia Eagles made a valiant comeback attempt Green Bay 013140-27 but fell just short in the final minutes of the season opener vs. Green Philadelphia 30710-20 Bay. Philadelphia fell behind 13-3 at half and 27-10 in the 4th quar- ter and lost four key players along the way: starting QB Kevin Kolb Phila - D.Akers, 45 FG (8-26, 4:00) (concussion), MLB Stewart Bradley (concussion), FB Leonard GB - M.Crosby, 49 FG (10-43, 5:31) Weaver (ACL), and C Jamaal Jackson (triceps). But behind the arm GB - D. Driver, 6 pass from Rodgers (Crosby) (11-76, 5:33) and legs of back-up signal caller Michael Vick, the Eagles rallied to GB - M.Crosby, 56 FG (7-39, 0:41) make the score 27-20 late in the 4th quarter. In fact, they took over GB - J.Kuhn, 3 run (Crosby) (10-62, 4:53) possession at their own 24-yard-line with 4:13 to play and drove to Phila - L.McCoy, 12 run (Akers) (9-60, 4:12) the GB42 before Vick was tackled short of a first down on a 4th-and- GB - G.Jennings, 32 pass from Rodgers (Crosby) (4-51, 2:28) 1 rushing attempt to seal the Packers victory. After the Eagles took Phila - J.Maclin, 17 pass from Vick (Akers) (9-79, 3:39) a 3-0 lead after an interception by Joselio Hanson, Green Bay took Phila - D.Akers, 24 FG (9-45, 3:31) control over the remainder of the first half. -

2009 Roster-Outlook.Indd

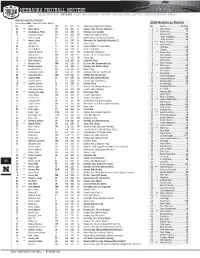

Nebraska football rosters | Coaching Staff | Outlook | Meet the Huskers | Review | Record Book | History | Administration | Media | 2009 Alphabetical Roster Lettermen in Bold; *-Indicates Letters Earned 2009 Numerical Roster No. Name Pos. Ht. Wt. Yr. Home town (High School/College) No. Name .......................... Position 95 ** Allen, Pierre DE 6-5 265 Jr. Denver, Colo. (Thomas Jefferson) 1 * Chris Brooks ...........................WR 21 ** Amukamara, Prince CB 6-1 200 Jr. Glendale, Ariz. (Apollo) 1 ** Adi Kunalic ..............................PK 70 Anderson, Kenny DE 6-2 250 RFr. Omaha, Neb. (Millard West) 2 Antonio Bell ...........................WR . 9 Ankrah, Jason DE 6-4 255 Fr. Gaithersburg, Md. (Quince Orchard) 2 Lazarri Middleton ....................DB 4 ** Asante, Larry S 6-1 215 Sr. Alexandria, Va. (Hayfield/Coffeyville CC) 3 Taylor Martinez .......................QB 3 *** Rickey Thenarse .........................S . 70 Ash, Nick OL 6-5 270 Fr. Keller, Texas 4 ** Larry Asante ...............................S 66 Barrett, Cruz OL 6-4 310 Jr. Daytona Beach, Fla. (Mainland) 4 Ty Kildow ...............................WR 91 Barry, Robert TE 6-8 220 Fr. Battle Creek, Neb. 5 Zac Lee ....................................QB 83 Bechtold, Damon TE 6-4 235 RFr. Omaha, Neb. (Westside) 5 ** Antony West ...........................CB 2 Bell, Antonio WR 6-2 180 Fr. Daytona Beach, Fla. (Mainland) 6 Khiry Cooper ..........................WR 39 Blatchford, Justin CB 6-1 195 RFr. Ponca, Neb. 7 Dejon Gomes ..........................CB 14 * Blue, Anthony CB 5-10 185 So. Cedar Hill, Texas 7 Kody Spano .............................QB 1 * Brooks, Chris WR 6-2 215 Sr. St. Louis, Mo. (Hazelwood East) 8 Austin Cassidy ............................S 72 ** Burkes, Jaivorio OL 6-5 295 Jr. Phoenix, Ariz. (Moon Valley) 8 ** Will Henry ..............................WR 22 Burkhead, Rex RB 5-11 200 Fr. -

Falcons Qb Michael Vick, Packers De Aaron Kampman & Cowboys Wr Sam Hurd Named Nfc Players of Week 8

NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE 280 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017 (212) 450-2000 * FAX (212) 681-7573 WWW.NFLMedia.com Joe Browne, Executive Vice President-Communications Greg Aiello, Vice President-Public Relations FOR USE AS DESIRED NFC-POW-8 11/1/06 FALCONS QB MICHAEL VICK, PACKERS DE AARON KAMPMAN & COWBOYS WR SAM HURD NAMED NFC PLAYERS OF WEEK 8 Quarterback MICHAEL VICK of the Atlanta Falcons, defensive end AARON KAMPMAN of the Green Bay Packers and rookie wide receiver SAM HURD of the Dallas Cowboys are the NFC Offensive, Defensive and Special Teams Players of the Week for games played the eighth week of the 2006 season (October 29-30), the NFL announced today. OFFENSE: QB MICHAEL VICK, ATLANTA FALCONS • On the road against the defending AFC North Division champions, Vick completed 20 of 28 passes (71.4 percent) for 291 yards with three touchdowns and no interceptions for a 140.6 passer rating in the Falcons’ 29-27 victory over the Cincinnati Bengals. Vick also rushed nine times for 55 yards (6.1 average). With Atlanta trailing 14-6 in the second quarter, the left-handed quarterback led the Falcons on a 10-play, 81- yard drive, culminating with a 16-yard touchdown pass to tight end ALGE CRUMPLER. On Atlanta’s first possession of the second half, the former Virginia Tech star guided the Falcons on a 65-yard drive, capping it with a 26-yard touchdown strike to wide receiver MICHAEL JENKINS to put Atlanta up 20-17. Later in the third quarter, Vick finished a 60-yard drive with an eight-yard TD pass to fullback JUSTIN GRIFFITH to put the Falcons ahead 26-20, a lead the club would not relinquish. -

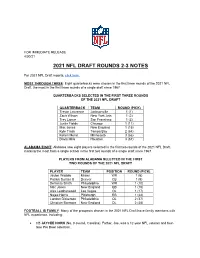

2021 Nfl Draft Rounds 2-3 Notes

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 4/30/21 2021 NFL DRAFT ROUNDS 2-3 NOTES For 2021 NFL Draft reports, click here. MOST THROUGH THREE: Eight quarterbacks were chosen in the first three rounds of the 2021 NFL Draft, the most in the first three rounds of a single draft since 1967. QUARTERBACKS SELECTED IN THE FIRST THREE ROUNDS OF THE 2021 NFL DRAFT QUARTERBACK TEAM ROUND (PICK) Trevor Lawrence Jacksonville 1 (1) Zach Wilson New York Jets 1 (2) Trey Lance San Francisco 1 (3) Justin Fields Chicago 1 (11) Mac Jones New England 1 (15) Kyle Trask Tampa Bay 2 (64) Kellen Mond Minnesota 3 (66) Davis Mills Houston 3 (67) ALABAMA EIGHT: Alabama saw eight players selected in the first two rounds of the 2021 NFL Draft, marking the most from a single school in the first two rounds of a single draft since 1967. PLAYERS FROM ALABAMA SELECTED IN THE FIRST TWO ROUNDS OF THE 2021 NFL DRAFT PLAYER TEAM POSITION ROUND (PICK) Jaylen Waddle Miami WR 1 (6) Patrick Surtain II Denver CB 1 (9) DeVonta Smith Philadelphia WR 1 (10) Mac Jones New England QB 1 (15) Alex Leatherwood Las Vegas OL 1 (17) Najee Harris Pittsburgh RB 1 (24) Landon Dickerson Philadelphia OL 2 (37) Christian Barmore New England DL 2 (38) FOOTBALL IS FAMILY: Many of the prospects chosen in the 2021 NFL Draft have family members with NFL experience, including: • CB JAYCEE HORN (No. 8 overall, Carolina): Father, Joe, was a 12-year NFL veteran and four- time Pro Bowl selection. • CB PATRICK SURTAIN II (No. -

Miami Dolphins San Francisco 49Ers

SAN FRANCISCO 49ERS MIAMI DOLPHINS NO NAME POS HT WT AGE EXP COLLEGE NO NAME POS HT WT AGE EXP COLLEGE NO NAME POS 2 David Akers K 5-10 200 38 14 Louisville 2 Brandon Fields P 6-5 245 28 6 Michigan State NO NAME POS 2 ...... Akers, David ........................K 3 Scott Tolzien QB 6-3 208 25 2 Wisconsin 5 Dan Carpenter K 6-2 225 26 5 Montana 29 ...... Amaya, Jonathon ................S 75 ...... Boone, Alex ......................G/T 4 Andy Lee P 6-2 180 30 9 Pittsburgh 7 Pat Devlin QB 6-3 225 24 2 Delaware 15 ...... Bess, Davone ...................WR 53 ...... Bowman, NaVorro .............LB 7 Colin Kaepernick QB 6-4 230 25 2 Nevada 8 Matt Moore QB 6-3 216 27 6 Oregon State 73 ...... Brown, Patrick ....................T 26 ...... Brock, Tramaine ................CB 11 Alex Smith QB 6-4 217 28 8 Utah 14 Marlon Moore WR 6-0 190 24 3 Fresno State 56 ...... Burnett, Kevin ...................LB 55 ...... Brooks, Ahmad ..................LB 15 Michael Crabtree WR 6-1 214 25 4 Texas Tech 15 Davone Bess WR 5-10 193 26 5 Hawaii 22 ...... Bush, Reggie .....................RB 25 ...... Brown, Tarell .....................CB 17 A.J. Jenkins WR 6-0 192 23 R Illinois 17 Ryan Tannehill QB 6-4 222 24 R Texas A&M 5 ...... Carpenter, Dan ....................K 81 ...... Celek, Garrett ................... TE 19 Ted Ginn Jr. WR 5-11 180 27 6 Ohio State 20 Reshad Jones S 6-1 210 24 3 Georgia 28 ...... Carroll, Nolan ...................CB 20 ...... Cox, Perrish .......................CB 20 Perrish Cox CB 6-0 190 25 2 Oklahoma State 22 Reggie Bush RB 6-0 203 27 6 Southern Cal 42 ..... -

Patriots at Philadelphia Game Notes

GAME NOTES New England Patriots at New York Giants - August 29, 2012 *Sebastian Vollmer made his 2012 preseason debut and was in the starting lineup at right tackle. Vollmer dressed for the Tampa Bay game but did not start. *QB Ryan Mallett made his second start of the preseason. He started in the Monday Night Football game against Philadelphia on Aug. 20 at Gillette Stadium. Mallett played through the first half before being relieved by Brian Hoyer. Mallett finished the game 8-of-15 for 40 yards. *Hoyer finished 9-of15 for 96 yards. The Patriots and Giants closed out the preseason for the eighth straight year. The Patriots lost to the Giants 6-3 and are now 2-6 in those games. *Of the seven 2012 draft picks, four were in the starting lineup against the Giants. Second-round pick Tavon Wilson started at safety, sixth-round pick Nate Ebner started at safety, seventh-round pick Alfonzo Dennard started at cornerback and seventh-round pick Jeremy Ebert started at wide receiver. *First round draft picks DL Chandler Jones and LB Dont’a Hightower did not start against the Giants after starting the first three preseason games. *DL Jermaine Cunningham had two sacks in the game. He registered a 14-yard sack of QB Eli Manning in the first quarter and a 7-yard sack of David Carr in the second quarter. Cunningham also had three hits on the quarterback and finished the preseason with six hits on the quarterback. *Rookie free agent RB Brandon Bolden started at running back and finished with 15 carries for 59 yards for a 3.9-yard average. -

06FB Guide P151-190.Pmd

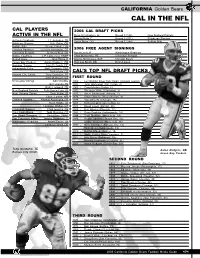

CALIFORNIA Golden Bears CAL IN THE NFL CAL PLAYERS 2006 CAL DRAFT PICKS ACTIVE IN THE NFL Ryan O’Callaghan, OL Round 5 (136) New England Patriots Marvin Philip, C Round 6 (201) Pittsburgh Steelers Arizona Cardinals J.J. Arrington, TB Aaron Merz, OG Round 7 (248) Buffalo Bills Baltimore Ravens Kyle Boller, QB Buffalo Bills Wendell Hunter, LB Carolina Panthers Lorenzo Alexander, DT 2006 FREE AGENT SIGNINGS Cincinnati Bengals Deltha O’Neal, CB David Lonie, P Washington Redskins Dallas Cowboys L.P. Ladouceur, SNAP Chris Manderino, FB Cincinnati Bengals Detroit Lions Nick Harris, P Donnie McCleskey, SAF Chicago Bears Green Bay Packers Aaron Rodgers, QB Harrison Smith, DB Detroit Lions Houston Texans Jerry DeLoach, DE Indianapolis Colts Matt Giordano, SAF Tarik Glenn, OT CAL’S TOP NFL DRAFT PICKS Kansas City Chiefs Tony Gonzalez, TE John Welbourn, OT FIRST ROUND Minnesota Vikings Adimchinobe 1952 - Les Richter (New York Yanks, 2nd pick overall) Echemandu, TB 1953 - John Olszewski (Chi. Cards, 4) Ryan Longwell, PK 1965 - Craig Morton (Dallas, 6) New England Patriots Tully Banta-Cain, LB 1972 - Sherman White (Cincinnati, 2) New Orleans Saints Scott Fujita, LB 1975 - Steve Bartkowski (Atlanta, 1) Chase Lyman, WR 1976 - Chuck Muncie (New Orleans, 3) Oakland Raiders Nnamdi Asomugha, CB 1977 - Ted Albrecht (Chicago, 15) Ryan Riddle, LB 1981 - Rich Campbell (Green Bay, 6) Langston Walker, OT 1984 - David Lewis (Detroit, 20) Pittsburgh Steelers Chidi Iwuoma, CB 1988 - Ken Harvey (Phoenix, 12) Saint Louis Rams Todd Steussie, OT 1993 - Sean Dawkins (Indianapolis, -

01 12 Recruiting.Indd

UUCLACLA - TThehe CCompleteomplete PPackageackage “UCLA has the most complete athletic program in the country” (Sports Illustrated On Campus - April ‘05 The Nation’s No. 1 Combined Academic, Social & Athletic Program Winner of more NCAA Championships than any other school; one of the nation’s top public universities; centrally located to beaches and mountains. An Outstanding Head Coach Jim Mora is a former NFC Coach of the Year with 25 seasons of NFL coaching experience. He has served as Head Coach of the Atlanta Falcons and the Seattle Seahawks and as the defen- sive coordinator of the San Francisco 49ers. Talented & Experienced Coaching Staff An experienced staff with diverse backgrounds, many with NFL experience as coaches and players. The goal of the staff is to develop greatness in UCLA’s student-athletes, both on and off the fi eld. Academic Support Learning specialists, tutoring aid, counseling and general assistance that is second to none. The Bruin Family UCLA provides a prosperous outlook for the future with internships, workshop mentoring programs and access to one of the world’s meccas of business, entertainment, media and networking. Media Rich Southern California USA Today, Fox Sports Net, NFL Network and ESPN have offi ces in LA. Seven local television stations and 13 area newspapers provide unparalleled coverage. The Next Step Over 25 Bruins populate NFL rosters on a yearly basis. At least one former Bruin has been on the roster of a Super Bowl team in 29 of the last 32 years. In 29 of the last 30 seasons, at least one Bruin has made a Pro Bowl roster. -

Falcons Offense Falcons Specialists Falcons

vs. SUNDAY, September 29, 2013 - Georgia Dome 2 Matt Ryan ..................................... QB FALCONS OFFENSE FALCONS DEFENSE 3 Stephen Gostkowski ........................ K 3 Matt Bryant ...................................... K 6 Ryan Allen ....................................... P WR 11 Julio Jones 83 Harry Douglas 15 Kevin Cone RE 50 Osi Umenyiora 99 Stansly Maponga 4 Dominique Davis ........................... QB 11 Julian Edelman............................. WR LT 72 Sam Baker 73 Ryan Schraeder 65 Jeremy Trueblood DT 91 Corey Peters 94 Peria Jerry 5 Matt Bosher ..................................... P 12 Tom Brady .................................... QB LG 63 Justin Blalock 69 Harland Gunn DT 95 Jonathan Babineaux 92 Travian Robertson 11 Julio Jones .................................. WR 15 Ryan Mallett .................................. QB C 66 Peter Konz 61 Joe Hawley 15 Kevin Cone ................................... WR LE 96 Jonathan Massaquoi 98 Cliff Matthews 93 Malliciah Goodman 17 Aaron Dobson .............................. WR RG 75 Garrett Reynolds 69 Harland Gunn 19 Drew Davis .................................. WR OLB 59 Joplo Bartu 53 Omar Gaither 18 Matthew Slater ............................. WR RT 76 Lamar Holmes 73 Ryan Schraeder 65 Jeremy Trueblood 21 Desmond Trufant .......................... CB MLB 52 Akeem Dent 55 Paul Worrilow 22 Stevan Ridley ................................ RB TE 88 Tony Gonzalez 86 Chase Coffman 80 Levine Toilolo 22 Asante Samuel .............................. CB OLB 54 Stephen Nicholas 51 -

The Parthenon, August 31, 2012

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar The aP rthenon University Archives 8-31-2012 The aP rthenon, August 31, 2012 John Gibb [email protected] Jeremy Johnson [email protected] Adam Rogers [email protected] Nikki Dotson [email protected] Joanie Borders [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon Recommended Citation Gibb, John; Johnson, Jeremy; Rogers, Adam; Dotson, Nikki; Borders, Joanie; and Adkins, Eden, "The aP rthenon, August 31, 2012" (2012). The Parthenon. Paper 114. http://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon/114 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aP rthenon by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors John Gibb, Jeremy Johnson, Adam Rogers, Nikki Dotson, Joanie Borders, and Eden Adkins This newspaper is available at Marshall Digital Scholar: http://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon/114 C M Y K 50 INCH FRIDAY August 31, 2012 VOL. 116 NO. 1 | MARSHALL UNIVERSITY’S STUDENT NEWSPAPER | MARSHALLPARTHENON.COM SENIOR’S FINAL SEASON | Page 2 MU VS. WVU PREVIEW | Page 2 CATO SET FOR BIG STAGE | Page 3 FOOTBALL EDITION C M Y K 50 INCH 2 FOOTBALL EDITION FRIDAY, AUGUST 31, 2012 | | MARSHALLPARTHENON.COM Coach Doc Holliday motivates his team 2012 Herd football schedule during a summer practice session on Aug. 29. The Herd looks to beat WVU at their last forseeable Friends of Coal Bowl game. MARCUS CONSTANTINO | THE PARTHENON When: Sept. -

2013 - 2014 Media Guide

2013 - 2014 MEDIA GUIDE www.bcsfootball.org The Coaches’ Trophy Each year the winner of the BCS National Champi- onship Game is presented with The Coaches’ Trophy in an on-field ceremony after the game. The current presenting sponsor of the trophy is Dr Pepper. The Coaches’ Trophy is a trademark and copyright image owned by the American Football Coaches As- sociation. It has been awarded to the top team in the Coaches’ Poll since 1986. The USA Today Coaches’ Poll is one of the elements in the BCS Standings. The Trophy — valued at $30,000 — features a foot- ball made of Waterford® Crystal and an ebony base. The winning institution retains The Trophy for perma- nent display on campus. Any portrayal of The Coaches’ Trophy must be li- censed through the AFCA and must clearly indicate the AFCA’s ownership of The Coaches’ Trophy. Specific licensing information and criteria and a his- tory of The Coaches’ Trophy are available at www.championlicensing.com. TABLE OF CONTENTS AFCA Football Coaches’ Trophy ............................................IFC Table of Contents .........................................................................1 BCS Media Contacts/Governance Groups ...............................2-3 Important Dates ...........................................................................4 The 2013-14 Bowl Championship Series ...............................5-11 The BCS Standings ....................................................................12 College Football Playoff .......................................................13-14 -

Football Weekly - by MATTHEW HATFIELD National Football League - Thursday, September 6Th, 2007

Football Weekly - BY MATTHEW HATFIELD National Football League - Thursday, September 6th, 2007 NBC Season Opener: Thursday - 9-6-07 New Orleans @ Indianapolis SU Pick: New Orleans 31-27 ATS Pick: NO +6 WEEK 1 PICKS: Sunday - 9-9-07 Atlanta @ Minnesota SU Pick: Atlanta 13-10 ATS Pick: ATL +3 Denver @ Buffalo SU Pick: Denver 28-16 ATS Pick: DEN -3 Carolina @ St. Louis SU Pick: Carolina 24-21 ATS Pick: CAR +1 Pittsburgh @ Cleveland SU Pick: Pittsburgh 20-0 ATS Pick: PIT -4.5 Philadelphia @ Green By SU Pick: Green Bay 16-13 ATS Pick: GB +3 Kansas City @ Houston SU Pick: Houston 30-14 ATS Pick: HOU -3 Tennessee @ Jacksonville SU Pick: Jacksonville 35-13 ATS Pick: JAG -6.5 Miami @ Washington SU Pick: Washington 17-7 ATS Pick: WSH -3 Ne w England @ NY Jets SU Pick: N. England 24-8 AT S Pick: NE -6.5 Chicago @ San Diego SU Pick: San Diego 27-9 ATS Pick: SD -6 Detroit @ Oakland SU Pick: Detroit 28-13 ATS Pick: DET +2 Tampa Bay @ Seattle SU Pick: Seattle 21-6 ATS Pick: SEA -6 NY Giants @ Dallas SU Pick: Dallas 23-14 ATS Pick: DAL -6 ESPN Monday Night Football PICKS: Monday - 9-10-07 Baltimore @ Cincinnati SU Pick: Cincinnati 24-10 ATS Pick: CIN -2.5 Arizona @ San Francisco SU Pick: San Fran 31-24 ATS Pick: SF -3 LOCKS: San Diego (POTW), Denver -3, Pittsburgh -4.5, New England -6.5 and Cincinnati -2.5 UPSET SPECIALS: Green Bay SU & +3 (UPOTW) and Atlanta SU & +3 INSIDE THE MATCHUPS: New Orleans Saints @ Indianapolis Colts Two electric offenses collide in this prime-time season opening meeting between the defending Super Bowl Champion Colts and NFC runner-up Saints.