Full Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004 Nfl Tv Plans, Announcers, Programming

NFL KICKS OFF WITH NATIONAL TV THURSDAY NIGHT GAME; NFL TV 2004 THE NFL is the only sports league that televises all regular-season and postseason games on free, over-the-air network television. This year, the league will kick off its 85th season with a national television Thursday night game in a rematch of the 2003 AFC Championship Game when the Indianapolis Colts visit the Super Bowl champion New England Patriots on September 9 (ABC, 9:00 PM ET). Following is a guide to the “new look” for the NFL on television in 2004: • GREG GUMBEL will host CBS’ The NFL Today. Also joining the CBS pregame show are former NFL tight end SHANNON SHARPE and reporter BONNIE BERNSTEIN. • JIM NANTZ teams with analyst PHIL SIMMS as CBS’ No. 1 announce team. LESLEY VISSER joins the duo as the lead sideline reporter. • Sideline reporter MICHELE TAFOYA joins game analyst JOHN MADDEN and play-by-play announcer AL MICHAELS on ABC’s NFL Monday Night Football. • FOX’s pregame show, FOX NFL Sunday, will hit the road for up to seven special broadcasts from the sites of some of the biggest games of the season. • JAY GLAZER joins FOX NFL Sunday as the show’s NFL insider. • Joining ESPN is Pro Football Hall of Fame member MIKE DITKA. Ditka will serve as an analyst on a variety of shows, including Monday Night Countdown, NFL Live, SportsCenter and Monday Quarterback. • SAL PAOLANTONIO will host ESPN’s EA Sports NFL Match-Up (formerly Edge NFL Match-Up). NFL ANNOUNCER LINEUP FOR 2004 ABC NFL Monday Night Football: Al Michaels-John Madden-Michele Tafoya (Reporter). -

New England Patriots

NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS Contact: Stacey James, Director of Media Relations or Anthony Moretti, Asst. Director or Michelle L. Murphy, Media Relations Asst. Gillette Stadium * One Patriot Place * Foxborough, MA 02035 * 508-384-9105 fax: 508-543-9053 [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] For Immediate Release, September 24, 2002 BATTLE OF DIVISION LEADERS – NEW ENGLAND (3-0) TRAVELS TO SAN DIEGO (3-0) MEDIA SCHEDULE This Week: The New England Patriots (3-0) will try to close out the month of September Wednesday, Sept. 25 as only the fifth team in franchise history to begin a campaign with a four-game winning streak when they trek cross-country to face the San Diego Chargers (3-0). The New 10:45-11:15 Head Coach Bill Belichick’s Press England passing attack, which is averaging an NFL-best 316 yards per game, will be Conference (Media Workroom) challenged by the Chargers top rated pass defense. San Diego’s defense leads the NFL, 11:15-11:55 Open Locker Room allowing only 132 passing yards per game and posting 16 sacks. The Patriots currently 12:40-12:55 Photographers Access to Practice hold a 10-game winning streak in the series, their longest against any opponent. The last TBA Chargers Player Conference Call time the Chargers defeated the Patriots was on Nov. 15, 1970. TBA Marty Schottenheimer Conference Call Television: This week’s game will be broadcasted nationally on CBS (locally on WBZ 3:10 Drew Brees National Conference Call Channel 4). The play-by-play duties will be handled by Greg Gumbel, who will be joined in the booth by Phil Simms. -

Game Summaries:IMG.Qxd

Sunday, September 12, 2010 Green Bay Packers 27 Lincoln Financial Field Philadelphia Eagles 20 Clad in their Kelly green uniforms in honor of the 1960 NFL cham- 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Pts pions, the Philadelphia Eagles made a valiant comeback attempt Green Bay 013140-27 but fell just short in the final minutes of the season opener vs. Green Philadelphia 30710-20 Bay. Philadelphia fell behind 13-3 at half and 27-10 in the 4th quar- ter and lost four key players along the way: starting QB Kevin Kolb Phila - D.Akers, 45 FG (8-26, 4:00) (concussion), MLB Stewart Bradley (concussion), FB Leonard GB - M.Crosby, 49 FG (10-43, 5:31) Weaver (ACL), and C Jamaal Jackson (triceps). But behind the arm GB - D. Driver, 6 pass from Rodgers (Crosby) (11-76, 5:33) and legs of back-up signal caller Michael Vick, the Eagles rallied to GB - M.Crosby, 56 FG (7-39, 0:41) make the score 27-20 late in the 4th quarter. In fact, they took over GB - J.Kuhn, 3 run (Crosby) (10-62, 4:53) possession at their own 24-yard-line with 4:13 to play and drove to Phila - L.McCoy, 12 run (Akers) (9-60, 4:12) the GB42 before Vick was tackled short of a first down on a 4th-and- GB - G.Jennings, 32 pass from Rodgers (Crosby) (4-51, 2:28) 1 rushing attempt to seal the Packers victory. After the Eagles took Phila - J.Maclin, 17 pass from Vick (Akers) (9-79, 3:39) a 3-0 lead after an interception by Joselio Hanson, Green Bay took Phila - D.Akers, 24 FG (9-45, 3:31) control over the remainder of the first half. -

02 Mg Divider Fronts

Former Hokie Michael Vick, the first player picked in the 2001 NFL Draft, is scheduled to take over the starting quarterback duties for the Atlanta Falcons in 2002. Special Teams are an integral part of Hokie football and one of the units is called “Pride and Joy.” These NFL players are also a source of pride and joy due to their commitment to Virginia Tech on and off the field. Virginia Tech has recently constructed a display in the Hall of Legends in the Merryman Athletic Center to honor such former players. John Engelberger was a dominating defensive end who went from walk-on to four-year starter at Tech, to second-round NFL Draft pick, earning All-America honors and his college degree along the way. Waddy Harvey was a standout who started three seasons at defensive tackle and won the coveted Williams Award for leadership and character before joining the Buffalo Bills. Frank and Cheryl Beamer sponsored Harvey for recognition on the Pride and Joy display. Before starting an NFL career, Jim Pyne, a powerful center in the early 1990s, started 41 games and allowed just one sack in over 2,700 snaps on his way to becoming the Hokies’ first unanimous All-American. Michael Vick was an electrifying quarterback who made a lasting impact on college football while helping Virginia Tech to a national championship game and back-to-back 11-1 seasons before becoming the top NFL pick in 2001. Jim Pyne was the first player chosen overall in the NFL’s 1998 expansion draft. Tech Players in the Pros The following former Hokies are either presently playing or have played in the National Football League or the United States Football League: (players in bold were active as of June 25, 2002) Larry Austin .................. -

— KEY TRANSACTIONS — Signed to the Baltimore Ravens' Practice Squad on 12/30/20 Waived by the Lions on 12/28/20 Signed By

— KEY TRANSACTIONS — Tied for the fourth-most total special teams tackles (14) in Signed to the Baltimore Ravens’ practice squad on 12/30/20 the NFL in 2018 Waived by the Lions on 12/28/20 — PERSONAL — Signed by the Detroit Lions on 3/27/20 Nephew of former three-time Pro Bowl DE Jevon Kearse and Originally selected by the Minnesota Vikings in the seventh cousin of former CB Phillip Buchanon round (244th overall) of the 2016 NFL Draft Actively involved in the Big Brothers, Big Sisters organization — CAREER HIGHLIGHTS — Has one daughter, Ja’riah Has played in 73 career games (12 starts), tallying 108 — 2020 SEASON HIGHLIGHTS — tackles (77 solo), 1 FF, 1 FR, 1 INT, a half-sack and 10 Signed to Baltimore’s practice squad on 12/31 after playing PD…Has also recorded 28 special teams tackles (21 solo) and 1 FR on special teams in 11 games (seven starts) for the Lions…Posted 55 tackles (38 solo), 1 QBH, 1 FF and 1 PD in Detroit, while also adding 3 In 2020, signed to Baltimore’s practice squad on 12/31/20 special teams tackles after playing in 11 games (seven starts) for the Lions…Posted 55 tackles (38 solo), 1 QBH, 1 FF and 1 PD in Posted 7 tackles (5 solo) and 1 PD at Ten. (12/20) Detroit, while also adding 3 special teams tackles Recorded 8 tackles (6 solo) and his first PD of the season at Has appeared in three playoff games, recording 2 special Chi. (12/6) teams tackles Tallied a career-high 9 tackles (8 solo) vs. -

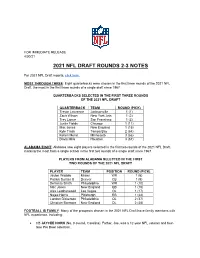

2021 Nfl Draft Rounds 2-3 Notes

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 4/30/21 2021 NFL DRAFT ROUNDS 2-3 NOTES For 2021 NFL Draft reports, click here. MOST THROUGH THREE: Eight quarterbacks were chosen in the first three rounds of the 2021 NFL Draft, the most in the first three rounds of a single draft since 1967. QUARTERBACKS SELECTED IN THE FIRST THREE ROUNDS OF THE 2021 NFL DRAFT QUARTERBACK TEAM ROUND (PICK) Trevor Lawrence Jacksonville 1 (1) Zach Wilson New York Jets 1 (2) Trey Lance San Francisco 1 (3) Justin Fields Chicago 1 (11) Mac Jones New England 1 (15) Kyle Trask Tampa Bay 2 (64) Kellen Mond Minnesota 3 (66) Davis Mills Houston 3 (67) ALABAMA EIGHT: Alabama saw eight players selected in the first two rounds of the 2021 NFL Draft, marking the most from a single school in the first two rounds of a single draft since 1967. PLAYERS FROM ALABAMA SELECTED IN THE FIRST TWO ROUNDS OF THE 2021 NFL DRAFT PLAYER TEAM POSITION ROUND (PICK) Jaylen Waddle Miami WR 1 (6) Patrick Surtain II Denver CB 1 (9) DeVonta Smith Philadelphia WR 1 (10) Mac Jones New England QB 1 (15) Alex Leatherwood Las Vegas OL 1 (17) Najee Harris Pittsburgh RB 1 (24) Landon Dickerson Philadelphia OL 2 (37) Christian Barmore New England DL 2 (38) FOOTBALL IS FAMILY: Many of the prospects chosen in the 2021 NFL Draft have family members with NFL experience, including: • CB JAYCEE HORN (No. 8 overall, Carolina): Father, Joe, was a 12-year NFL veteran and four- time Pro Bowl selection. • CB PATRICK SURTAIN II (No. -

Nfl Nicknames

Superstitions, Cont’d. T Daniel Loper, Tennessee Puts his equipment on left to right in game order for every practice and game. QB Peyton Manning, Indianapolis Reads the game program cover to cover before every game. RB Moran Norris, San Francisco Does not walk under the cross bars before games. FB Mike Sellers, Washington Does not eat before a game, even if it’s a night game. WR Maurice Stovall, Tampa Bay Gets his hair cut every Friday and watches a Bruce Lee movie before every game. CB Charles Tillman, Chicago Has the same person stretch him and tape him. DE Jason Taylor, Miami Does everything from right to left. K Lawrence Tynes, Giants Washes his car before every home game. LB Brian Urlacher, Chicago Eats a couple of chocolate chip cookies before every game. NFL NICKNAMES “Peanut” may not be the first nickname that usually comes to mind for an NFL player, but that’s exactly the name Chicago Bears corner back CHARLES TILLMAN has gone by since childhood. But the nicknames get even more creative — Jacksonville Jaguars quarterback BYRON LEFTWICH gave his teammate MAURICE JONES-DREW the nickname “Pinball” after the way defenders bounced off the running back during training camp last year. Ranging in origin from athletic ability to size or demeanor, these nicknames give a creative insight into the players they have been given to. Here are some other interesting NFL player nicknames: PLAYER NICKNAME DERIVATION Anthony Adams, Chi. “Double A” Teammates say he moves constantly, just like the Energizer Bunny. Keith Adams, Miami “The Bullet” Runs down the field as fast as he can and zeroes in on his target. -

New England Patriots Vs . New Orleans Saints

NEW EN GLA N D PATRIOTS VS . NEW ORLEA N S SAI N TS # NAME ................ POS Thursday, August 12, 2010 • 7:30 p.m. • Gillette Stadium # NAME ................ POS 3 Stephen Gostkowski .........K 4 Sean Canfield ................. QB 7 Zac Robinson ................ QB 5 Garrett Hartley...................K 8 Brian Hoyer .................. QB PATRIOTS OFFENSE PATRIOTS DEFENSE 6 Thomas Morstead ..............P 10 Darnell Jenkins ............WR 9 Drew Brees .................... QB 11 Julian Edelman ..............WR LE: 94 Ty Warren 91 Myron Pryor 96 Jermaine Cunningham WR: 83 Wes Welker 19 Brandon Tate 88 Sam Aiken 10 Chase Daniel .................. QB 90 Darryl Richard 12 Tom Brady .................... QB 18 Matthew Slater 17 Taylor Price 15 Rod Owens 11 Patrick Ramsey ............... QB NT: 75 Vince Wilfork 97 Ron Brace 74 Kyle Love 14 Zoltan Mesko ...................P LT: 72 Matt Light 76 Sebastian Vollmer 66 George Bussey 12 Marques Colston ............ WR 15 Rod Owens ...................WR 13 Rod Harper .................... WR RE: 99 Mike Wright 68 Gerard Warren 92 Damione Lewis 17 Taylor Price ...................WR LG: 70 Logan Mankins* 63 Dan Connolly 71 Eric Ghiaciuc 14 Andy Tanner .................. WR 18 Matthew Slater ..............WR 71 Brandon Deaderick 66 Kade Weston OLB: 95 Tully Banta-Cain 58 Pierre Woods 93 Marques Murrell 15 Courtney Roby ............... WR 19 Brandon Tate ................WR C: 67 Dan Koppen 63 Dan Connolly 69 Ryan Wendell 16 Lance Moore .................. WR 21 Fred Taylor ....................RB ILB: 51 Jerod Mayo 52 Eric Alexander 44 Tyrone McKenzie 17 Robert Meachem ............ WR RG: 61 Stephen Neal 60 Rich Ohrnberger 62 Ted Larsen 22 Terrence Wheatley .........CB 18 Larry Beavers ................ WR 65 Darnell Stapleton 23 Leigh Bodden .................CB ILB: 59 Gary Guyton 55 Brandon Spikes 48 Thomas Williams 19 Devery Henderson ........ -

The Following Players Comprise the College Football Great Teams 2 Card Set

COLLEGE FOOTBALL GREAT TEAMS OF THE PAST 2 SET ROSTER The following players comprise the College Football Great Teams 2 Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. Players in bold are starters. If there is a difference between the player's card and the roster sheet, always use the card information. The number in ()s after the player name is the number of cards that the player has in this set. See below for a more detailed explanation of new symbols on the cards. 1971 NEBRASKA 1971 NEBRASKA 1972 USC 1972 USC OFFENSE DEFENSE OFFENSE DEFENSE EB: Woody Cox End: John Adkins EB: Lynn Swann TA End: James Sims Johnny Rodgers (2) TA TB, OA Willie Harper Edesel Garrison Dale Mitchell Frosty Anderson Steve Manstedt John McKay Ed Powell Glen Garson TC John Hyland Dave Boulware (2) PA, KB, KOB Tackle: John Grant Tackle: Carl Johnson Tackle: Bill Janssen Chris Chaney Jeff Winans Daryl White Larry Jacobson Tackle: Steve Riley John Skiles Marvin Crenshaw John Dutton Pete Adams Glenn Byrd Al Austin LB: Jim Branch Cliff Culbreath LB: Richard Wood Guard: Keith Wortman Rich Glover Guard: Mike Ryan Monte Doris Dick Rupert Bob Terrio Allan Graf Charles Anthony Mike Beran Bruce Hauge Allan Gallaher Glen Henderson Bruce Weber Monte Johnson Booker Brown George Follett Center: Doug Dumler Pat Morell Don Morrison Ray Rodriguez John Kinsel John Peterson Mike McGirr Jim Stone ET: Jerry List CB: Jim Anderson TC Center: Dave Brown Tom Bohlinger Brent Longwell PC Joe Blahak Marty Patton CB: Charles Hinton TB. -

Jets Expansion Draft Plan Coming Into Focus? Signing Dano Could Be Indicator

Winnipeg Sun http://www.winnipegsun.com/2017/06/13/jets-expansion-draft-plan-coming-into-focus Jets expansion draft plan coming into focus? Signing Dano could be indicator BY KEN WIEBE, WINNIPEG SUN There are still several moving parts and a few issues left to uncover or resolve, but the expansion plans for the Winnipeg Jets are coming into focus. While it's still unclear whether the Jets asked veteran defenceman Toby Enstrom to waive his no-movement clause before Monday's deadline, you'd have to think the conversation took place. When Jets GM Kevin Cheveldayoff was asked directly about the topic of no-movement clauses at his year-end address, he said all options would be explored. Officially, the Jets won't be commenting on the process until after the protected lists are revealed on Sunday morning. Based on experience, one shouldn't expect too much detail to be given, even after the expansion draft picks are made public. It's a sensitive subject and one of the biggest reasons the NHL GM's didn't want the lists to be made public. Yes, it's possible the Jets could buy out the final year of Enstrom's $5.75 million contract, but that appears to be the most unlikely result. The Jets haven't bought out a player since the franchise relocated and it's hard to imagine Enstrom would be the first, especially since they still value his services when healthy. Buying him out would be both a costly proposition and leave a void on the left side of the defence depth chart. -

Hokies�To�Watch�…

SPRINGFOOTBALL2001 Virginia Tech Head Coach Frank Beamer André Davis David Pugh Lee Suggs Ben Taylor Jarrett Ferguson VIRGINIA POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE AND STATE UNIVERSITY OtherHokiesToWatch… 24 Larry Austin 47 Wayne Briggs 46 Chris Buie 20 Keith Burnell 28 Lamar Cobb 99 Cols Colas CB, r-Sr. FB, r-Sr. LB, r-So. TB, r-Jr. DE, r-Jr. DE, r-So. 21 Michael Crawford 57 Anthony Davis 95 Jim Davis 61 Steve DeMasi 60 Jacob Gibson 1 Eric Green ROV, r-So. OT, Jr. DE, So. C, r-Sr. OG, r-So. CB, So. 64 Jake Grove 25 Billy Hardee 41 Jake Houseright 23 T.J. Jackson 70 Kevin Lewis 5 Kevin McCadam C, r-So. CB, r-Jr. LB, Sr. LB, r-Jr. DT, So. LB, Sr. 82 Ronald Moody 67 Anthony Nelson 11 Grant Noel 74 Luke Owens 9 Terrell Parham 89 Robert Peaslee SE, r-So. OG, r-So. QB, r-Jr. OG, r-Jr. FL, r-Jr. P, r-So. 35 Willie Pile 3 Deon Provitt 53 Channing Reed 6 Vegas Robinson 87 Bob Slowikowski 49 Carter Warley FS, r-Jr. LB, r-So. DT, Sr. LB, r-So. TE, r-Sr. PK, r-So. 34 Brian Welch 19 Ernest Wilford 54 Dan Wilkinson 86 Keith Willis 58 Matt Wincek 26 Shawn Witten LB, r-Sr. SE, r-So. DT, r-Sr. TE, r-So. OT, Sr. FL, Jr. Virginia Tech Football Media Information 2001 Schedule Date Opponent Location ITINERARY: Spring practice is scheduled to run from Sept. 1 CONNECTICUT Blacksburg, Va. March 24 through April 21. -

DENVER BRONCOS NEWS RELEASE Week 1 • Denver (0-0) Vs

DENVER BRONCOS NEWS RELEASE Week 1 • Denver (0-0) vs. Kansas City (0-0) • INVESCO Field at Mile High • 6:30 p.m. (MDT) BRONCOS BATTLE DIVISION RIVAL KANSAS CITY IN MEDIA RELATIONS CONTACT INFORMATION SEASON OPENER AT INVESCO FIELD AT MILE HIGH Jim Saccomano (303) 649-0572 [email protected] Let the games begin! The Paul Kirk (303) 649-0503 [email protected] Denver Broncos kickoff the Mark Cicero (303) 649-0512 [email protected] 2004 season at home against Patrick Smyth (303) 649-0536 [email protected] their division rival, the Rebecca Villanueva (303) 649-0598 [email protected] Kansas City Chiefs, on Sunday, Sept. 12 at INVESCO WWW.DENVERBRONCOS.COM/MEDIAROOM The Denver Broncos have a media-only website, which was Field at Mile High. The game created to assist accredited media in their coverage of the will be shown in the national Broncos. By going to www.DenverBroncos.com/Mediaroom, spotlight of ESPN’s Sunday members of the press will find complete statistical packages, Night Football (and locally on press releases, rosters, updated player and coach bios, the 2004 KUSA-TV, Channel 9) with Broncos Media Guide, game recaps and much more. Feature the kickoff scheduled for 6:30 p.m. (MDT). clippings are also available as one complete packet, and broken This is the fourth time these teams have faced each other in down individually by player and coach. Game clippings will also be the season opener. The Broncos hold a 3-1 advantage, with all posted weekly throughout the season.