Adjectives and the Syntax of German(Ic) Dps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice | RSACVP 2017 | 6-9 April 2017 | Suceava – Romania Rethinking Social Action

Available online at: http://lumenpublishing.com/proceedings/published-volumes/lumen- proceedings/rsacvp2017/ 8th LUMEN International Scientific Conference Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice | RSACVP 2017 | 6-9 April 2017 | Suceava – Romania Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice The Convertor Status of Article of Case and Number in the Romanian Language Diana-Maria ROMAN* https://doi.org/10.18662/lumproc.rsacvp2017.62 How to cite: Roman, D.-M. (2017). The Convertor Status of Article of Case and Number in the Romanian Language. In C. Ignatescu, A. Sandu, & T. Ciulei (eds.), Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice (pp.682-694). Suceava, Romania: LUMEN Proceedings https://doi.org/10.18662/lumproc.rsacvp2017.62 © The Authors, LUMEN Conference Center & LUMEN Proceedings. Selection and peer-review under responsibility of the Organizing Committee of the conference 8th LUMEN International Scientific Conference Rethinking Social Action. Core Values in Practice | RSACVP 2017 | 6-9 April 2017 | Suceava – Romania The Convertor Status of Article of Case and Number in the Romanian Language Diana-Maria ROMAN1* Abstract This study is the outcome of research on the grammar of the contemporary Romanian language. It proposes a discussion of the marked nominalization of adjectives in Romanian, the analysis being focused on the hypostases of the convertor (nominalizer). Within this area of research, contemporary scholarly treaties have so far accepted solely nominalizers of the determinative article type (definite and indefinite) and nominalizers of the vocative desinence type, in the singular. However, with regard to the marked conversion of an adjective to the large class of nouns, the phenomenon of enclitic articulation does not always also entail the individualization of the nominalized adjective, as an expression of the category of definite determination. -

Possessive Agreement Turned Into a Derivational Suffix Katalin É. Kiss 1

Possessive agreement turned into a derivational suffix Katalin É. Kiss 1. Introduction The prototypical case of grammaticalization is a process in the course of which a lexical word loses its descriptive content and becomes a grammatical marker. This paper discusses a more complex type of grammaticalization, in the course of which an agreement suffix marking the presence of a phonologically null pronominal possessor is reanalyzed as a derivational suffix marking specificity, whereby the pro cross-referenced by it is lost. The phenomenon in question is known from various Uralic languages, where possessive agreement appears to have assumed a determiner-like function. It has recently been a much discussed question how the possessive and non-possessive uses of the agreement suffixes relate to each other (Nikolaeva 2003); whether Uralic definiteness-marking possessive agreement has been grammaticalized into a definite determiner (Gerland 2014), or it has preserved its original possessive function, merely the possessor–possessum relation is looser in Uralic than in the Indo-Europen languages, encompassing all kinds of associative relations (Fraurud 2001). The hypothesis has also been raised that in the Uralic languages, possessive agreement plays a role in organizing discourse, i.e., in linking participants into a topic chain (Janda 2015). This paper helps to clarify these issues by reconstructing the grammaticalization of possessive agreement into a partitivity marker in Hungarian, the language with the longest documented history in the Uralic family. Hungarian has two possessive morphemes functioning as a partitivity marker: -ik, an obsolete allomorph of the 3rd person plural possessive suffix, and -(j)A, the productive 3rd person singular possessive suffix. -

Annual Report

2008 Annual Report Center for Language and Cognition Groningen Faculty of Arts, University of Groningen 2 Contents Foreword 5 Part One 1 Introduction 9 1.1 Institutional Embedding 9 1.2 Profile 9 2 CLCG in 2008 10 2.1 Structure 10 2.2 Director, Advisory Board, Coordinators 10 2.3 Assessment 11 2.4 Staffing 11 2.5 Finances: Travel and Material costs 12 2.6 Internationalization 12 2.7 Contract Research 13 3 Research Activities 14 3.1 Conferences, Cooperation, and Colloquia 14 3.1.1 TABU-day 2008 14 3.1.2 Groningen conferences 14 3.1.3 Conferences elsewhere 15 3.1.4 Visiting scholars 16 3.1.5 Linguistics Colloquium 17 3.1.6 Other lectures 18 3.2 CLCG-Publications 18 3.3 PhD Training Program 18 3.3.1 Graduate students 21 3.4 Postdocs 21 Part Two 4 Research Groups 25 4.1 Computational Linguistics 25 4.2 Discourse and Communication 39 4.3. Language and Literacy Development Across the Life Span 49 4.4. Language Variation and Language Change 61 4.5. Neurolinguistics 71 4.6. Syntax and Semantics 79 Part Three 5. Research Staff 2008 93 3 4 Foreword The Center for Language and Cognition, Groningen (CLCG) continued its research into 2008, making it an exciting place to work. On behalf of CLCG I am pleased to present the 2008 annual report. Highlights of this year s activities were the following. Five PhD theses were defended: • Starting a Sentence in Dutch: A corpus study of subject- and object-fronting (Gerlof Bouma). -

Of Trees and Birds : a Festschrift for Gisbert Fanselow

J. M. M. Brown | Andreas Schmidt | Marta Wierzba (Eds.) OF TREES AND BIRDS A Festschrift for Gisbert Fanselow Universitätsverlag Potsdam OF TREES AND BIRDS J. M. M. Brown | Andreas Schmidt | Marta Wierzba (Eds.) OF TREES AND BIRDS A Festschrift for Gisbert Fanselow Universitätsverlag Potsdam Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de/ abrufbar. Universitätsverlag Potsdam 2019 http://verlag.ub.uni-potsdam.de/ Am Neuen Palais 10, 14469 Potsdam Tel.: +49 (0)331 977 2533 / Fax: 2292 E-Mail: [email protected] Soweit nicht anders gekennzeichnet ist dieses Werk unter einem Creative Commons Lizenzvertrag lizenziert: Namensnennung 4.0 International Um die Bedingungen der Lizenz einzusehen, folgen Sie bitte dem Hyperlink: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de Umschlaggestaltung: Sarah Pertermann Druck: docupoint GmbH Magdeburg ISBN 978-3-86956-457-9 Zugleich online veröffentlicht auf dem Publikationsserver der Universität Potsdam: https://doi.org/10.25932/publishup-42654 https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-426542 Contents Preface ................................. xiii J.M. M. Brown, Andreas Schmidt, Marta Wierzba I Morphological branch 1 The instrumental -er suffix ..................... 3 Susan Olsen Bienenfresserortungsversuch: compounding with clause-embedding heads .................... 15 Barbara Stiebels Leben mit Paradoxien ........................ 27 Manfred Bierwisch Zur Analysierbarkeit adverbieller Konnektive ......... 37 Ilse Zimmermann Measuring lexical semantic variation using word embeddings ........................ 61 Damir Cavar II Syntactic branch 75 Intermediate reflexes of movement: A problem for TAG? .. 77 Doreen Georgi Towards a Fanselownian analysis of degree expressions ... 95 Julia Bacskai-Atkari v A form-function mismatch? The case of Greek deponents . -

Hunsrik-Xraywe.!A!New!Way!In!Lexicography!Of!The!German! Language!Island!In!Southern!Brazil!

Dialectologia.!Special-issue,-IV-(2013),!147+180.!! ISSN:!2013+2247! Received!4!June!2013.! Accepted!30!August!2013.! ! ! ! ! HUNSRIK-XRAYWE.!A!NEW!WAY!IN!LEXICOGRAPHY!OF!THE!GERMAN! LANGUAGE!ISLAND!IN!SOUTHERN!BRAZIL! Mateusz$MASELKO$ Austrian$Academy$of$Sciences,$Institute$of$Corpus$Linguistics$and$Text$Technology$ (ICLTT),$Research$Group$DINAMLEX$(Vienna,$Austria)$ [email protected]$ $ $ Abstract$$ Written$approaches$for$orally$traded$dialects$can$always$be$seen$controversial.$One$could$say$ that$there$are$as$many$forms$of$writing$a$dialect$as$there$are$speakers$of$that$dialect.$This$is$not$only$ true$ for$ the$ different$ dialectal$ varieties$ of$ German$ that$ exist$ in$ Europe,$ but$ also$ in$ dialect$ language$ islands$ on$ other$ continents$ such$ as$ the$ Riograndese$ Hunsrik$ in$ Brazil.$ For$ the$ standardization$ of$ a$ language$ variety$ there$ must$ be$ some$ determined,$ general$ norms$ regarding$ orthography$ and$ graphemics.!Equipe!Hunsrik$works$on$the$standardization,$expansion,$and$dissemination$of$the$German$ dialect$ variety$ spoken$ in$ Rio$ Grande$ do$ Sul$ (South$ Brazil).$ The$ main$ concerns$ of$ the$ project$ are$ the$ insertion$of$Riograndese$Hunsrik$as$official$community$language$of$Rio$Grande$do$Sul$that$is$also$taught$ at$school.$Therefore,$the$project$team$from$Santa$Maria$do$Herval$developed$a$writing$approach$that$is$ based$on$the$Portuguese$grapheme$inventory.$It$is$used$in$the$picture$dictionary! Meine!ëyerste!100! Hunsrik! wërter$ (2010).$ This$ article$ discusses$ the$ picture$ dictionary$ -

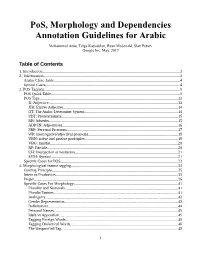

Pos, Morphology and Dependencies Annotation Guidelines for Arabic

PoS, Morphology and Dependencies Annotation Guidelines for Arabic Mohammed Attia, Tolga Kayadelen, Ryan Mcdonald, Slav Petrov Google Inc. May, 2017 Table of Contents 1. Introduction............................................................................................................................................2 2. Tokenization...........................................................................................................................................3 Arabic Clitic Table................................................................................................................................4 Special Cases.........................................................................................................................................4 3. POS Tagging..........................................................................................................................................8 POS Quick Table...................................................................................................................................8 POS Tags.............................................................................................................................................13 JJ: Adjective....................................................................................................................................13 JJR: Elative Adjective.....................................................................................................................14 DT: The Arabic Determiner System...............................................................................................14 -

5 Adjectives and Adverbs

5 ADJECTIVES AND ADVERBS 1 Choose the correct alternative in the sentences below. If you find both alternatives acceptable, explain any difference in meaning. a. All the venues are easy/easily accessible. b. There’s a possible/possibly financial problem. c. We admired the wonderful/wonderfully panorama. d. Our neighbours are (simple)/simply people who live near us. Although less likely in this case, the adjective “simple” could be used as a premodifier to describe the noun (that is, the neighbours are not sophisticated people). Since the sentence seems to be a more general description of neighbours, however, the adverb “simply” is the more likely choice. The adverb serves as a comment on the part of the speaker. e. They seemed happy/happily about George’s victory. f. Similar/Similarly teams of medical advisers were called upon. g. Something in here smells horrible/horribly. Normally an adjective will follow a linking verb to describe a quality of the subject ref- erent. However, the adverb “horribly” can be used to refer to the intensity of the smell. h. This cream will give you a beautiful/beautifully smooth complexion. i. Particular/Particularly groups such as recent immigrants felt their needs were being overlooked. INTRODUCING ENGLISH GRAMMAR, THIRD EDITION KEY TO EXERCISES 5 Adjectives and Adverbs The adjective “particular” premodifies or describes the noun “groups”, whereas the use of the adverb “particularly” functions as a comment on the part of the speaker. 2 Explain the difference in form and meaning between the members of each pair. a. 1 She is a natural blonde. -

Adverbial Reinforcement of Demonstratives in Dialectal German

Glossa a journal of general linguistics Adverbial reinforcement of COLLECTION: NEW PERSPECTIVES demonstratives in dialectal ON THE NP/DP DEBATE German RESEARCH PHILIPP RAUTH AUGUSTIN SPEYER *Author affiliations can be found in the back matter of this article ABSTRACT CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Philipp Rauth In the German dialects of Rhine and Moselle Franconian, demonstratives are Universität des Saarlandes, reinforced by locative adverbs do/lo ‘here/there’ in order to emphasize their deictic Germany strength. Interestingly, these adverbs can also appear in the intermediate position, i.e., [email protected] between the demonstrative and the noun (e.g. das do Bier ‘that there beer’), which is not possible in most other varieties of European German. Our questionnaire study and several written and oral sources suggest that reinforcement has become mandatory in KEYWORDS: demonstrative contexts. We analyze this grammaticalization process as reanalysis of demonstrative; reinforcer; do/lo from a lexical head to the head of a functional Index Phrase. We also show that a German; Rhine Franconian; functional DP-shell can better cope with this kind of syntactic change and with certain Moselle Franconian; Germanic; serialization facts concerning adjoined adjectives. Romance; dialectal German; grammaticalization; reanalysis; NP; DP; questionnaire TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Rauth, Philipp and Augustin Speyer. 2021. Adverbial reinforcement of demonstratives in dialectal German. Glossa: a journal of general linguistics 6(1): 4. 1–24. DOI: https://doi. org/10.5334/gjgl.1166 1 INTRODUCTION Rauth and Speyer 2 Glossa: a journal of In colloquial Standard German, the only difference between definite determiners (1a) and general linguistics DOI: 10.5334/gjgl.1166 demonstratives is emphatic stress in demonstrative contexts (1b). -

SOEP-IS 2018—ILANGUAGE: Variables from Innovative Language Modules

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics DIW Berlin / SOEP (Ed.) Research Report SOEP-IS 2018 - ILANGUAGE: Variables from innovative language modules SOEP Survey Papers, No. 851 Provided in Cooperation with: German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) Suggested Citation: DIW Berlin / SOEP (Ed.) (2020) : SOEP-IS 2018 - ILANGUAGE: Variables from innovative language modules, SOEP Survey Papers, No. 851, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW), Berlin This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/219075 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative -

University of Education, Winneba College Of

University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION, WINNEBA COLLEGE OF LANGUAGES EDUCATION, AJUMAKO THE SYNTAX OF THE GONJA NOUN PHRASE JACOB SHAIBU KOTOCHI May, 2017 i University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION, WINNEBA COLLEGE OF LANGUAGES EDUCATION, AJUMAKO THE SYNTAX OF THE GONJA NOUN PHRASE JACOB SHAIBU KOTOCHI 8150260007 A thesis in the Department of GUR-GONJA LANGUAGES EDUCATION, COLLEGE OF LANGUAGES EDUCATION, submitted to the school of Graduate Studies, UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION, WINNEBA in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the Master of Philosophy in Ghanaian Language Studies (GONJA) degree. ii University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh DECLARATION I, Jacob Shaibu Kotochi, declare that this thesis, with the exception of quotations and references contained in published works and students creative writings which have all been identified and duly acknowledged, is entirely my own original work, and it has not been submitted, either in part or whole, for another degree elsewhere. Signature: …………………………….. Date: …………………………….. SUPERVISOR’S DECLARATION I, Dr. Samuel Awinkene Atintono, hereby declare that the preparation and presentation of this thesis were supervised in accordance with the guidelines for supervision of thesis as laid down by the University of Education, Winneba. Signature: …………………………….. Date: …………………………….. iii University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to express my gratitude to Dr. Samuel Awinkene Atintono of the Department of Gur-Gonja Languages Education, College of Languages Education for being my guardian, mentor, lecturer and supervisor throughout my university Education and the writing of this research work. -

Am-Progressives in Swabian: Some Evidence for Noun Incorporation

AM-PROGRESSIVES IN SWABIAN: SOME EVIDENCE FOR NOUN INCORPORATION Bettina Spreng University of Saskatchewan 1. Introduction This paper summarizes the initial findings of an investigation into the syntactic and semantic properties of progressive constructions in Swabian, an Alemannic dialect of German. It is spoken in the Southwest of Germany in the state of Baden Württemberg and in parts of Bavaria. The data is elicited from speakers of a variant of Swabian spoken in Upper Swabia, an area surrounding the city of Ravensburg, located north of Lake Constance. Data was elicited from three female speakers of different ages (48, 69, 75) with low mobility. There is very little in-depth work on the syntactic properties of Swabian and, to my knowledge, no work on this particular variant. The construction that is being investigated is found in various dialects and registers of German but tends to be relegated to footnotes or assumed to be restricted to dialects in the Rhineland area, especially Cologne (Duden 2005). It is thus often named the Rhenish Progressive ‘Rheinische Verlaufsform’ in some of the descriptive and theoretical literature (Thieroff 1992, Vater 1994). However, the construction may be found in various variants of German including written German (Gárgyán 2014) despite many descriptive grammars insisting that it is restricted to one or two dialect areas or to the vernacular (Fagan 2009, Duden 2005). It thus deserves a closer look. The construction I am particularly interested in is the AM- progressive that seems to share some properties with the BEIM-progressive. Some work addressing the construction has been done for individual dialects such as Colognian (Bhatt and Schmidt 1993), Standard, Ruhr, and Low German (Andersson 1989), and Hessian (Flick and Kuhmichel 2013). -

Contents German Pronunciation &Accents

Contents German Pronunciation &Accents Geo-social Applications of the Natural Phonetics & Tonetics Method 9 1. Foreword 10 The meaning of International German 11 Why doing Phonetics? H Typography & canlPA symbols 17 2. Pronunciation & Phonetics 20 7he Phonetic Method 29 3- The phono-articulatory apparatus 33 The vocalfolds 3« Resonators (five cavities) 39 The lips 43 4- The Classification of sounds 47 5- Vowels & vocoids 52 7he vowels & diphthongs of international German 55 6. Consonants & contoids 56 Places and manners of articulation 59 7- The consonants of international German 59 Nasals 60 Stops 61 Stop-strictives (or 'affricates') 62 Constrictives (or fricatives') 63 Approximants 64 Laterals 65 8. Structures 65 Taxophonics 69 Stress 75 9- Reduced forms 87 10. Intonation «9 Tunings 90 Protunes 90 Tunes 93 German intonation 99 11. Some texts in phonotonetic transcription (3 http://d-nb.info/1053287356 6 German Pronunciation & Accents Native accents 105 12. Neutral German pronunciation 105 Vowels & Diphthongs 111 Consonants 112 Nasals 116 Stops 122 Stop-strictives (or affricates') 123 Constrictives (or 'fricatives') 126 Approximants 126 Laterals 127 Intonation 129 13- Traditional German pronunciation 133 14. Mediatic German pronunciation 143 15- North-east Germany 149 16. Austria 155 17- Switzerland 163 18. South Tyrol (or Alto Adige, Italy) Regional accents 171 19- Germany (18) 179 Far North-west (Schleswig-Holstein: Kiel) 181 North Saxony (Hamburg) 183 yffestphalia (Düsseldorf) 185 North Rhenia (Essen) 187 Eastphalia (Hannover) 18p Mecklenburg (Rostock) lpo Brandenburg (Berlin) 194 Middle Rhenia (Cologne/Köln) 198 South Rhenia (Trier) 199 Hesse (Frankfurt) 201 Palatinate (Mannheim) 202 'Thuringia (Erfurt) 204 Saxony (Dresden) 208 Franconia (Würzburg) 211 South Franconia (Karlsuhe) 213 Swabia (Stuttgart) 216 Baden (Freiburg) 218 North Bavaria (Amberg) 220 Bavaria (Munich/München) 223 20.