The Official Ubuntu Book.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin Issue 12

Issue 12 Bulletin June 2008 ries of short videos about GNU and Contents free software. The first video, which will be airing on gnu.org to coincide GNU is 25! 1 with the anniversary, explains free soft- ware to a new generation of people, The Wikipedia 2 and encourages them to download and Naming Controversy try gNewSense. These videos, coupled with a fresh new look for gnu.org and The Last Mile is 4 upcoming membership events in Port- Always the Hardest land and San Francisco, promise to make the 25th anniversary something The Free Software 6 really special. Jobs Page You can help too! We are looking for any relics of GNU and FSF history Volunteer Spotlight: 7 that you may have lying around. If Yavor Doganov they’re something you can email, feel free to send them to campaigns@fsf. End Software 9 org, and if they’re something a little Patents more tangible, drop us a line and if they’re something of interest, we’d love Free Software 11 to see them. Supporter The most important thing of course is that GNU continues to grow, and continues to stand up for freedom in a potentially hostile world. Twenty- GNU is 25! five years ago, the threats to our free- dom came from proprietary operat- by Matt Lee ing systems. Thankfully these days, Campaigns Manager we have a few completely free dis- fter some difficult developmental tributions of the GNU operating sys- Ayears, this September marks the tem, but we must not become compla- 25th birthday of GNU, and we’re go- cent. -

FY 2011 Annual Report

We're software roadies. Software Freedom Conservancy is a public charity that acts as a non-profit home for dozens of Free, Libre, and Open Source Software (FLOSS) projects. Conservancy©s charitable mission is to help improve, develop, and defend FLOSS, and we do that by providing business, legal, and administrative services to our member projects. We have the honor of working with member projects comprised of, in our humble opinion, many of the best software developers in the world. Some of our member projects develop system software so ubiquitous that it permeates virtually every part of our society©s electronics-driven lifestyle. Other member projects are redefining how software will be written and even how computer science will be taught to the next generation of developers. Still others find their niche by solving a small-but- persistent problem better than anyone else ± and attract a cult following of users because of it. And, best of all, all of our member projects release their software under a license that allows the public to study, use, improve, and share the source code. Conservancy provides all of our ªrock starº member projects with a comprehensive suite of services, and then we get out of their way to let them do what they do best: write great software for the public©s benefit. Our structure. Conservancy acts as a fiscal sponsor to our member projects. We©ve engaged the leadership of each member project©s developer community and executed a fiscal sponsorship agreement that allows us to adopt that project as an official part of Conservancy©s corporate structure. -

Read PDF Linux-Distribusjoner: Ubuntu, Fedora

[PDF] Linux-distribusjoner: Ubuntu, Fedora, Slackware, Mandriva Linux, Splashtop, Kubuntu, Debian, Mark Shuttleworth, Linux Mint, Gobuntu Linux-distribusjoner: Ubuntu, Fedora, Slackware, Mandriva Linux, Splashtop, Kubuntu, Debian, Mark Shuttleworth, Linux Mint, Gobuntu Book Review Absolutely one of the best pdf We have ever read. I really could comprehended every little thing using this written e book. I am easily could get a satisfaction of reading a written publication. (Dr. Od ie Ham ill) LINUX-DISTRIBUSJONER: UBUNTU, FEDORA , SLA CKWA RE, MA NDRIVA LINUX, SPLA SHTOP, KUBUNTU, DEBIA N, MA RK SHUTTLEW ORTH, LINUX MINT, GOBUNTU - To read Linux - distribusjoner: Ubuntu, Fedora, Slackware, Mandriva Linux , Splashtop, Kubuntu, Debian, Mark Shuttleworth, Linux Mint, Gobuntu PDF, you should follow the hyperlink beneath and save the ebook or gain access to other information which are highly relevant to Linux-distribusjoner: Ubuntu, Fedora, Slackware, Mandriva Linux, Splashtop, Kubuntu, Debian, Mark Shuttleworth, Linux Mint, Gobuntu book. » Download Linux -distribusjoner: Ubuntu, Fedora, Slackware, Mandriva Linux , Splashtop, Kubuntu, Debian, Mark Shuttleworth, Linux Mint, Gobuntu PDF « Our solutions was launched using a want to serve as a total on the internet electronic digital catalogue which offers usage of multitude of PDF document collection. You may find many different types of e-book along with other literatures from the paperwork database. Particular popular issues that distributed on our catalog are famous books, answer key, exam test questions and answer, guide example, practice guideline, quiz trial, customer manual, user guide, service instruction, maintenance manual, and so forth. All e-book all privileges remain together with the writers, and downloads come as is. -

Full Circle Magazine #33 Contents ^ Full Circle Ubuntu Women P.28

full circle ISSUE #33 - January 2010 CCRREEAATTEE AA MMEEDDIIAA CCEENNTTEERR WWIITTHH UUBBUUNNTTUU,, AANN AACCEERR RREEVVOO && BBOOXXEEEE full circle magazine #33 contents ^ full circle Ubuntu Women p.28 Program In Python - Pt7 p.08 Ubuntu Games p.31 My Story p.19 MOTU Interview p.24 Read how Ubuntu is used in public education, and why one man made the switch to Linux. Ubuntu, Revo & Boxee p.13 Command & Conquer p.05 The Perfect Server - Pt3 p.15 Review - Exaile p.23 Letters p.26 Top 5 - Sync. Clients p.35 The articles contained in this magazine are released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. This means you can adapt, copy, distribute and transmit the articles but only under the following conditions: You must attribute the work to the original author in some way (at least a name, email or URL) and to this magazine by name ('full circle magazine') and the URL www.fullcirclemagazine.org (but not attribute the article(s) in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you must distribute the resulting work under the same, similar or a compatible license. full circle magazine #33 contents ^ EDITORIAL This magazine was created using : Welcome to another issue of Full Circle magazine. ast month, Andrew gave us his Top 5 Media Center applications. This month I've written a How-To on using Ubuntu on an Acer Aspire Revo to create the foundation for Boxee. For under £150 I've created a fantastic media center L which not only looks great, it's fully customizable! That's my media center story, but don't forget to read the My Story articles which this month focus on Ubuntu, Linux and open-source in public education, as well as how one man went from using old (modern at the time) computers, to using Ubuntu. -

Linux Journal | August 2014 | Issue

™ SPONSORED BY Since 1994: The Original Magazine of the Linux Community AUGUST 2014 | ISSUE 244 | www.linuxjournal.com PROGRAMMING HOW-TO: + OpenGL Build, Develop Programming and Validate Creation of RPMs USE VAGRANT Sysadmin Cloud for an Easier Troubleshooting Development with dhclient Workflow Tips for PROMISE Becoming a THEORY Web Developer An In-Depth A Rundown Look of Linux for Recreation V WATCH: ISSUE OVERVIEW LJ244-Aug2014.indd 1 7/23/14 6:56 PM Get the automation platform that makes it easy to: Build Infrastructure Deploy Applications Manage In your data center or in the cloud. getchef.com LJ244-Aug2014.indd 2 7/23/14 11:41 AM Are you tiredtiered of of dealing dealing with with proprietary proprietary storage? storage? ® 9%2Ä4MHÆDCÄ2SNQ@FD ZFS Unified Storage zStax StorCore from Silicon - From modest data storage needs to a multi-tiered production storage environment, zStax StorCore zStax StorCore 64 zStax StorCore 104 The zStax StorCore 64 utilizes the latest in The zStax StorCore 104 is the flagship of the dual-processor Intel® Xeon® platforms and fast zStax product line. With its highly available SAS SSDs for caching. The zStax StorCore 64 configurations and scalable architecture, the platform is perfect for: zStax StorCore 104 platform is ideal for: VPDOOPHGLXPRIILFHILOHVHUYHUV EDFNHQGVWRUDJHIRUYLUWXDOL]HGHQYLURQPHQWV VWUHDPLQJYLGHRKRVWV PLVVLRQFULWLFDOGDWDEDVHDSSOLFDWLRQV VPDOOGDWDDUFKLYHV DOZD\VDYDLODEOHDFWLYHDUFKLYHV TalkTalk with with an anexpert expert today: today: 866-352-1173 866-352-1173 - http://www.siliconmechanics.com/zstax LJ244-Aug2014.indd 3 7/23/14 11:41 AM AUGUST 2014 CONTENTS ISSUE 244 PROGRAMMING FEATURES 64 Vagrant 74 An Introduction to How to use Vagrant to create a OpenGL Programming much easier development workflow. -

Ubuntu Kung Fu

Prepared exclusively for Alison Tyler Download at Boykma.Com What readers are saying about Ubuntu Kung Fu Ubuntu Kung Fu is excellent. The tips are fun and the hope of discov- ering hidden gems makes it a worthwhile task. John Southern Former editor of Linux Magazine I enjoyed Ubuntu Kung Fu and learned some new things. I would rec- ommend this book—nice tips and a lot of fun to be had. Carthik Sharma Creator of the Ubuntu Blog (http://ubuntu.wordpress.com) Wow! There are some great tips here! I have used Ubuntu since April 2005, starting with version 5.04. I found much in this book to inspire me and to teach me, and it answered lingering questions I didn’t know I had. The book is a good resource that I will gladly recommend to both newcomers and veteran users. Matthew Helmke Administrator, Ubuntu Forums Ubuntu Kung Fu is a fantastic compendium of useful, uncommon Ubuntu knowledge. Eric Hewitt Consultant, LiveLogic, LLC Prepared exclusively for Alison Tyler Download at Boykma.Com Ubuntu Kung Fu Tips, Tricks, Hints, and Hacks Keir Thomas The Pragmatic Bookshelf Raleigh, North Carolina Dallas, Texas Prepared exclusively for Alison Tyler Download at Boykma.Com Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their prod- ucts are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and The Pragmatic Programmers, LLC was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters or in all capitals. The Pragmatic Starter Kit, The Pragmatic Programmer, Pragmatic Programming, Pragmatic Bookshelf and the linking g device are trademarks of The Pragmatic Programmers, LLC. -

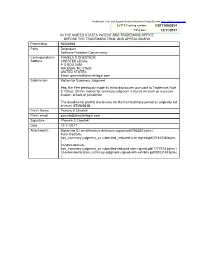

SFLC V Conservancy

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA863914 Filing date: 12/11/2017 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Proceeding 92066968 Party Defendant Software Freedom Conservancy Correspondence PAMELA S CHESTECK Address CHESTEK LEGAL P O BOX 2492 RALEIGH, NC 27602 UNITED STATES Email: [email protected] Submission Motion for Summary Judgment Yes, the Filer previously made its initial disclosures pursuant to Trademark Rule 2.120(a); OR the motion for summary judgment is based on claim or issue pre- clusion, or lack of jurisdiction. The deadline for pretrial disclosures for the first testimony period as originally set or reset: 07/20/2018 Filer's Name Pamela S Chestek Filer's email [email protected] Signature /Pamela S Chestek/ Date 12/11/2017 Attachments Motion for SJ on affirmative defenses-signed.pdf(756280 bytes ) Kuhn-Declara- tion_summary-judgment_as-submitted_reduced-size-signed.pdf(2181238 bytes ) Sandler-declara- tion_summary-judgment_as-submitted-reduced-size-signed.pdf(1777273 bytes ) Chestek declaration_summary-judgment-signed-with-exhibits.pdf(2003142 bytes ) IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD In the Mater of Registraion No. 4212971 Mark: SOFTWARE FREEDOM CONSERVANCY Registraion date: September 25, 2012 Sotware Freedom Law Center Peiioner, v. Cancellaion No. 92066968 Sotware Freedom Conservancy Registrant. RESPONDENT’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT ON ITS AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSES Introducion The Peiioner, Sotware Freedom Law Center (“SFLC”), is a provider of legal services. It had the idea to create an independent enity that would ofer inancial and administraive services for free and open source sotware projects. -

Download the Specification

Internationalizing and Localizing Applications in Oracle Solaris Part No: E61053 November 2020 Internationalizing and Localizing Applications in Oracle Solaris Part No: E61053 Copyright © 2014, 2020, Oracle and/or its affiliates. License Restrictions Warranty/Consequential Damages Disclaimer This software and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish, or display any part, in any form, or by any means. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of this software, unless required by law for interoperability, is prohibited. Warranty Disclaimer The information contained herein is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, please report them to us in writing. Restricted Rights Notice If this is software or related documentation that is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone licensing it on behalf of the U.S. Government, then the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT END USERS: Oracle programs (including any operating system, integrated software, any programs embedded, installed or activated on delivered hardware, and modifications of such programs) and Oracle computer documentation or other Oracle data delivered to or accessed by U.S. Government end users are "commercial -

18 Free Ways to Download Any Video Off the Internet Posted on October 2, 2007 by Aseem Kishore Ads by Google

http://www.makeuseof.com/tag/18-free-ways-to-download-any-video-off-the-internet/ 18 Free Ways To Download Any Video off the Internet posted on October 2, 2007 by Aseem Kishore Ads by Google Download Videos Now download.cnet.com Get RealPlayer® & Download Videos from the web. 100% Secure Download. Full Movies For Free www.YouTube.com/BoxOffice Watch Full Length Movies on YouTube Box Office. Absolutely Free! HD Video Players from US www.20north.com/ Coby, TV, WD live, TiVo and more. Shipped from US to India Video Downloading www.VideoScavenger.com 100s of Video Clips with 1 Toolbar. Download Video Scavenger Today! It seems like everyone these days is downloading, watching, and sharing videos from video-sharing sites like YouTube, Google Video, MetaCafe, DailyMotion, Veoh, Break, and a ton of other similar sites. Whether you want to watch the video on your iPod while working out, insert it into a PowerPoint presentation to add some spice, or simply download a video before it’s removed, it’s quite essential to know how to download, convert, and play these videos. There are basically two ways to download videos off the Internet and that’s how I’ll split up this post: either via a web app or via a desktop application. Personally, I like the web applications better simply because you don’t have to clutter up and slow down your computer with all kinds of software! UPDATE: MakeUseOf put together an excellent list of the best websites for watching movies, TV shows, documentaries and standups online. -

The GNOME Census: Who Writes GNOME?

The GNOME Census: Who writes GNOME? Dave Neary & Vanessa David, Neary Consulting © Neary Consulting 2010: Some rights reserved Table of Contents Introduction.........................................................................................3 What is GNOME?.............................................................................3 Project governance...........................................................................3 Why survey GNOME?.......................................................................4 Scope and methodology...................................................................5 Tools and Observations on Data Quality..........................................7 Results and analysis...........................................................................10 GNOME Project size.......................................................................10 The Long Tail..................................................................................11 Effects of commercialisation..........................................................14 Who does the work?.......................................................................15 Who maintains GNOME?................................................................17 Conclusions........................................................................................22 References.........................................................................................24 Appendix 1: Modules included in survey...........................................25 2 Introduction What -

GNU Guix Cookbook Tutorials and Examples for Using the GNU Guix Functional Package Manager

GNU Guix Cookbook Tutorials and examples for using the GNU Guix Functional Package Manager The GNU Guix Developers Copyright c 2019 Ricardo Wurmus Copyright c 2019 Efraim Flashner Copyright c 2019 Pierre Neidhardt Copyright c 2020 Oleg Pykhalov Copyright c 2020 Matthew Brooks Copyright c 2020 Marcin Karpezo Copyright c 2020 Brice Waegeneire Copyright c 2020 Andr´eBatista Copyright c 2020 Christine Lemmer-Webber Copyright c 2021 Joshua Branson Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled \GNU Free Documentation License". i Table of Contents GNU Guix Cookbook ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 1 Scheme tutorials ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 2 1.1 A Scheme Crash Course :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 2 2 Packaging :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 5 2.1 Packaging Tutorial:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 5 2.1.1 A \Hello World" package :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 5 2.1.2 Setup:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 8 2.1.2.1 Local file ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 8 2.1.2.2 `GUIX_PACKAGE_PATH' ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 9 2.1.2.3 Guix channels ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 10 2.1.2.4 Direct checkout hacking:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 10 2.1.3 Extended example :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: -

Linux at 25 PETERHISTORY H

Linux at 25 PETERHISTORY H. SALUS Peter H. Salus is the author of A n June 1991, at the USENIX conference in Nashville, BSD NET-2 was Quarter Century of UNIX (1994), announced. Two months later, on August 25, Linus Torvalds announced Casting the Net (1995), and The his new operating system on comp.os.minix. Today, Android, Google’s Daemon, the Gnu and the Penguin I (2008). [email protected] version of Linux, is used on over two billion smartphones and other appli- ances. In this article, I provide some history about the early years of Linux. Linus was born into the Swedish minority of Finland (about 5% of the five million Finns). He was a “math guy” throughout his schooling. Early on, he “inherited” a Commodore VIC- 20 (released in June 1980) from his grandfather; in 1987 he spent his savings on a Sinclair QL (released in January 1984, the “Quantum Leap,” with a Motorola 68008 running at 7.5 MHz and 128 kB of RAM, was intended for small businesses and the serious hobbyist). It ran Q-DOS, and it was what got Linus involved: One of the things I hated about the QL was that it had a read-only operating system. You couldn’t change things ... I bought a new assembler ... and an editor.... Both ... worked fine, but they were on the microdrives and couldn’t be put on the EEPROM. So I wrote my own editor and assembler and used them for all my programming. Both were written in assembly language, which is incredibly stupid by today’s standards.