Our Knowledge of the Clitoris by Karly Rath Department of Sociology A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

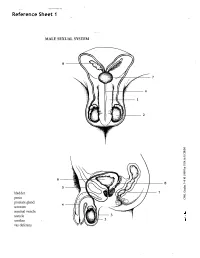

Reference Sheet 1

MALE SEXUAL SYSTEM 8 7 8 OJ 7 .£l"00\.....• ;:; ::>0\~ <Il '"~IQ)I"->. ~cru::>s ~ 6 5 bladder penis prostate gland 4 scrotum seminal vesicle testicle urethra vas deferens FEMALE SEXUAL SYSTEM 2 1 8 " \ 5 ... - ... j 4 labia \ ""\ bladderFallopian"k. "'"f"";".'''¥'&.tube\'WIT / I cervixt r r' \ \ clitorisurethrauterus 7 \ ~~ ;~f4f~ ~:iJ 3 ovaryvagina / ~ 2 / \ \\"- 9 6 adapted from F.L.A.S.H. Reproductive System Reference Sheet 3: GLOSSARY Anus – The opening in the buttocks from which bowel movements come when a person goes to the bathroom. It is part of the digestive system; it gets rid of body wastes. Buttocks – The medical word for a person’s “bottom” or “rear end.” Cervix – The opening of the uterus into the vagina. Circumcision – An operation to remove the foreskin from the penis. Cowper’s Glands – Glands on either side of the urethra that make a discharge which lines the urethra when a man gets an erection, making it less acid-like to protect the sperm. Clitoris – The part of the female genitals that’s full of nerves and becomes erect. It has a glans and a shaft like the penis, but only its glans is on the out side of the body, and it’s much smaller. Discharge – Liquid. Urine and semen are kinds of discharge, but the word is usually used to describe either the normal wetness of the vagina or the abnormal wetness that may come from an infection in the penis or vagina. Duct – Tube, the fallopian tubes may be called oviducts, because they are the path for an ovum. -

Gender, Sexism, Sexual Prejudice, and Identification with U.S. Football and Men's Figure Skating

Sex Roles (2016) 74:464–471 DOI 10.1007/s11199-016-0598-x Gender, Sexism, Sexual Prejudice, and Identification with U.S. Football and Men’s Figure Skating Woojun Lee1 & George B. Cunningham2 Published online: 24 February 2016 # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2016 Abstract Prejudice against lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans- Prejudice against lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender gender (LGBT) individuals can affect a number of attitudes (LGBT) individuals can affect a number of attitudes and be- and behaviors relevant to sports; however, there is compara- haviors relevant to sports. Parents with anti-LGBT attitudes tively little focus on sexual prejudice among sport fans. As are unlikely to let their children on teams coached by sexual such, the purpose of the present study was to examine the minorities (Cunningham and Melton 2012), and there is a associations among sexual prejudice, sexism, gender, and similar pattern among former players and their willingness identification with two sports: men’s figure skating and U.S. to play for LGBT coaches (Sartore and Cunningham 2009). football. To examine these associations, we draw from multi- In sport organizations, sexual prejudice is associated with a ple perspectives, including Robinson and Trail’s(2005)work reticence to support diversity initiatives (Cunningham and on identification, Herek’s(2007, 2009) sexual stigma and Sartore 2010), lesbian coaches report their sexual orientation prejudice theory, and McCormack and Anderson’s(2014a, being Bused^ against them by opposing coaches in the 2014b) theory of homohysteria. Questionnaire data were col- recruiting process (Krane and Barber 2005), and some lected from 150 students (52 women, 98 men) enrolled at a LGBT employees report feeling the need to hide their identi- large, public university in the Southwest United States. -

Physiology of Female Sexual Function and Dysfunction

International Journal of Impotence Research (2005) 17, S44–S51 & 2005 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0955-9930/05 $30.00 www.nature.com/ijir Physiology of female sexual function and dysfunction JR Berman1* 1Director Female Urology and Female Sexual Medicine, Rodeo Drive Women’s Health Center, Beverly Hills, California, USA Female sexual dysfunction is age-related, progressive, and highly prevalent, affecting 30–50% of American women. While there are emotional and relational elements to female sexual function and response, female sexual dysfunction can occur secondary to medical problems and have an organic basis. This paper addresses anatomy and physiology of normal female sexual function as well as the pathophysiology of female sexual dysfunction. Although the female sexual response is inherently difficult to evaluate in the clinical setting, a variety of instruments have been developed for assessing subjective measures of sexual arousal and function. Objective measurements used in conjunction with the subjective assessment help diagnose potential physiologic/organic abnormal- ities. Therapeutic options for the treatment of female sexual dysfunction, including hormonal, and pharmacological, are also addressed. International Journal of Impotence Research (2005) 17, S44–S51. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3901428 Keywords: female sexual dysfunction; anatomy; physiology; pathophysiology; evaluation; treatment Incidence of female sexual dysfunction updated the definitions and classifications based upon current research and clinical practice. -

A Handy Guide to the Male and Female Reproductive Tracts

BASICS OF LIFE BY LES SELLNOW eproduction in all species borders on the miraculous. at the reproductive organs of both the mare and the stallion How else can one describe a process where two infini- and discuss just how they function in their effort to produce Rtesimal entities, one from the male, the other from the another “miracle.” Once again, sources are too numerous to female, join forces to produce living, breathing offspring? mention, other than to say that much of the basic informa- Reproductive capability or success varies by species. Mice tion on reproduction available today stems from research at and rabbits, for example, are prolific producers of offspring. such institutions as Colorado State University, Texas A&M Horses, on the other hand, fall into a category where it is University, and the University of Minnesota. There are many much more chancy. others involved in reproductive research, but much of the in- When horses ran wild, this wasn’t a serious problem. There formation utilized in this article emanated from those three were so many of them that their numbers continued to ex- institutions. pand even though birth rate often was dictated by the avail- ability of food and water. Once the horse was domesticated, The Mare however, organized reproduction became the order of the We’ll begin with the mare because her role in the repro- day. Stables that depend on selling the offspring of stallions ductive process is more complicated than that of the stallion. and mares have an economic stake in breeding success. Yet, Basically, the mare serves four functions: the process continues to be less than perfect, with success 1) She produces eggs or ova; rates hovering in the 65-70% range, and sometimes lower. -

Women and Anger: the Roles of Gender, Sex Role, and Feminist Identity in Women's Anger Expression and Experience Susan Renee Stock-Ward Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1995 Women and anger: the roles of gender, sex role, and feminist identity in women's anger expression and experience Susan Renee Stock-Ward Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons, Personality and Social Contexts Commons, Psychiatry and Psychology Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Stock-Ward, Susan Renee, "Women and anger: the roles of gender, sex role, and feminist identity in women's anger expression and experience " (1995). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 11089. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/11089 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Hius, some thesis and dissertation copies are in Qpewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. Hie qnality of this reprodnction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photogr^hs, print bleedthrough, sul»tandard margins, and improper alignment can adversety affect reproductioa In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Comparative Morphology of the Penis and Clitoris in Four Species of Moles

RESEARCH ARTICLE Comparative Morphology of the Penis and Clitoris in Four Species of Moles (Talpidae) ADRIANE WATKINS SINCLAIR1∗, STEPHEN GLICKMAN2, KENNETH CATANIA3, AKIO SHINOHARA4, LAWRENCE BASKIN1, 1 AND GERALD R. CUNHA 1Department of Urology, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California 2Departments of Psychology and Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, California 3Department of Biological Sciences, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee 4Frontier Science Research Center, University of Miyazaki, Kihara, Japan ABSTRACT The penile and clitoral anatomy of four species of Talpid moles (broad-footed, star-nosed, hairy- tailed, and Japanese shrew moles) were investigated to define penile and clitoral anatomy and to examine the relationship of the clitoral anatomy with the presence or absence of ovotestes. The ovotestis contains ovarian tissue and glandular tissue resembling fetal testicular tissue and can produce androgens. The ovotestis is present in star-nosed and hairy-tailed moles, but not in broad-footed and Japanese shrew moles. Using histology, three-dimensional reconstruction, and morphometric analysis, sexual dimorphism was examined with regard to a nine feature mascu- line trait score that included perineal appendage length (prepuce), anogenital distance, and pres- ence/absence of bone. The presence/absence of ovotestes was discordant in all four mole species for sex differentiation features. For many sex differentiation features, discordance with ovotestes was observed in at least one mole species. The degree of concordance with ovotestes was highest for hairy-tailed moles and lowest for broad-footed moles. In relationship to phylogenetic clade, sex differentiation features also did not correlate with the similarity/divergence of the features and presence/absence of ovotestes. -

Vaginal Health After Breast Cancer: a Guide for Patients

Information Sheet Vaginal health after breast cancer: A guide for patients Key points • Women who have had breast cancer treatment before menopause may develop a range of symptoms related to low oestrogen levels, while post-menopausal women may have a worsening of their symptoms. • These symptoms relate to both the genital and urinary tracts. • A range of both non-prescription/lifestyle and prescription treatments is available. Discuss your symptoms with your specialist or general practitioner as they will be able to advise you, based on your individual situation. • Women who have had breast cancer treatment before menopause might find they develop symptoms such as hot flushes, night sweats, joint aches and vaginal dryness. • These are symptoms of low oestrogen, which occur naturally with age, but may also occur in younger women undergoing treatment for breast cancer. These changes are called the genito-urinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), which was previously known as atrophic vaginitis. • Unlike some menopausal symptoms, such as hot flushes, which may go away as time passes, vaginal dryness, discomfort with intercourse and changes in sexual function often persist and may get worse with time. • The increased use of adjuvant treatments (medications that are used after surgery/chemotherapy/radiotherapy), which evidence shows reduce the risk of the cancer recurring, unfortunately leads to more side-effects. • Your health and comfort are important, so don’t be embarrassed about raising these issues with your doctor. • This Information Sheet offers some advice for what you can do to maintain the health of your vagina, your vulva (the external genitals) and your urethra (outlet from the bladder), with special attention to the needs of women who have had breast cancer treatment. -

A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2002 A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays. Bonny Ball Copenhaver East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Copenhaver, Bonny Ball, "A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays." (2002). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 632. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/632 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays A dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis by Bonny Ball Copenhaver May 2002 Dr. W. Hal Knight, Chair Dr. Jack Branscomb Dr. Nancy Dishner Dr. Russell West Keywords: Gender Roles, Feminism, Modernism, Postmodernism, American Theatre, Robbins, Glaspell, O'Neill, Miller, Williams, Hansbury, Kennedy, Wasserstein, Shange, Wilson, Mamet, Vogel ABSTRACT The Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays by Bonny Ball Copenhaver The purpose of this study was to describe how gender was portrayed and to determine how gender roles were depicted and defined in a selection of Modern and Postmodern American plays. -

Glossary of Terms

Term English Definition Abstinence Sexual abstinence is not having vaginal, anal or oral sex. Acne Secretions from the skin's oil glands that plug the pores. Antibiotics Powerful medicines that fight bacterial infections. Anus The anus is the opening in the buttock where waste leaves the body. Bacteria A type of germ that can cause infections. Cervix the lower, narrow part of the uterus (womb) located between the bladder and the rectum. It forms a canal that opens into the vagina, which leads to the outside of the body. Chlamydia Chlamydia is caused by a type of bacteria, which can be passed from person to person during vaginal sex, oral sex, or anal sex. Condoms Condoms come in male and female versions. The male condom (“rubber”) covers the penis and catches the sperm after a man ejaculates. The female condom is a thin plastic pouch that lines the vagina. Consent Permission for something to happen or be done, or agreement to do something. Contraception Intentional use of methods or techniques to prevent pregnancy. Discharge Fluid that carries dead cells and bacteria out of the vagina. Estrogen a group of hormones secreted by the ovaries which affect many aspects of the female body, including a woman's menstrual cycle and normal sexual and reproductive development. Fallopian Tube One of two tubes through which an egg travels from the ovary to the uterus. Fertile the ability to become pregnant. Genital Herbes Genital herpes is a sexually transmitted infection (STI). It is caused by a virus called herpes simplex virus (HSV). Gonorrhea Gonorrhea is caused by bacteria that can be passed to a partner during vaginal, anal, or oral sex. -

The Mythical G-Spot: Past, Present and Future by Dr

Global Journal of Medical research: E Gynecology and Obstetrics Volume 14 Issue 2 Version 1.0 Year 2014 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-4618 & Print ISSN: 0975-5888 The Mythical G-Spot: Past, Present and Future By Dr. Franklin J. Espitia De La Hoz & Dra. Lilian Orozco Santiago Universidad Militar Nueva Granada, Colombia Summary- The so-called point Gräfenberg popularly known as "G-spot" corresponds to a vaginal area 1-2 cm wide, behind the pubis in intimate relationship with the anterior vaginal wall and around the urethra (complex clitoral) that when the woman is aroused becomes more sensitive than the rest of the vagina. Some women report that it is an erogenous area which, once stimulated, can lead to strong sexual arousal, intense orgasms and female ejaculation. Although the G-spot has been studied since the 40s, disagreement persists regarding the translation, localization and its existence as a distinct structure. Objective: Understand the operation and establish the anatomical points where the point G from embryology to adulthood. Methodology: A literature search in the electronic databases PubMed, Ovid, Elsevier, Interscience, EBSCO, Scopus, SciELO was performed. Results: descriptive articles and observational studies were reviewed which showed a significant number of patients. Conclusion: Sexual pleasure is a right we all have, and women must find a way to feel or experience orgasm as a possible experience of their sexuality, which necessitates effective stimulation. Keywords: G Spot; vaginal anatomy; clitoris; skene’s glands. GJMR-E Classification : NLMC Code: WP 250 TheMythicalG-SpotPastPresentandFuture Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2014. -

Anatomy and Physiology Male Reproductive System References

DEWI PUSPITA ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY MALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM REFERENCES . Tortora and Derrickson, 2006, Principles of Anatomy and Physiology, 11th edition, John Wiley and Sons Inc. Medical Embryology Langeman, pdf. Moore and Persaud, The Developing Human (clinically oriented Embryologi), 8th edition, Saunders, Elsevier, . Van de Graff, Human anatomy, 6th ed, Mcgraw Hill, 2001,pdf . Van de Graff& Rhees,Shaum_s outline of human anatomy and physiology, Mcgraw Hill, 2001, pdf. WHAT IS REPRODUCTION SYSTEM? . Unlike other body systems, the reproductive system is not essential for the survival of the individual; it is, however, required for the survival of the species. The RS does not become functional until it is “turned on” at puberty by the actions of sex hormones sets the reproductive system apart. The male and female reproductive systems complement each other in their common purpose of producing offspring. THE TOPIC : . 1. Gamet Formation . 2. Primary and Secondary sex organ . 3. Male Reproductive system . 4. Female Reproductive system . 5. Female Hormonal Cycle GAMET FORMATION . Gamet or sex cells are the functional reproductive cells . Contain of haploid (23 chromosomes-single) . Fertilizationdiploid (23 paired chromosomes) . One out of the 23 pairs chromosomes is the determine sex sex chromosome X or Y . XXfemale, XYmale Gametogenesis Oocytes Gameto Spermatozoa genesis XY XX XX/XY MALE OR FEMALE....? Male Reproductive system . Introduction to the Male Reproductive System . Scrotum . Testes . Spermatic Ducts, Accessory Reproductive Glands,and the Urethra . Penis . Mechanisms of Erection, Emission, and Ejaculation The urogenital system . Functionally the urogenital system can be divided into two entirely different components: the urinary system and the genital system. -

FAQ042 -- You and Your Sexuality (Especially for Teens)

AQ FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS FAQ042 fESPECIALLY FOR TEENS You and Your Sexuality (Especially for Teens) • What happens during puberty? • What emotional changes occur during puberty? • How are sexual feelings expressed? • What is masturbation? • What is oral sex? • What happens during sexual intercourse? • What can I do if I want to have sexual intercourse but I do not want to get pregnant? • How can I protect myself and my partner from sexual transmitted infections during sexual intercourse? • What is anal sex? • What does it mean to be gay, lesbian, or bisexual? • Can I choose to be attracted to someone of the same sex? • What is gender identity? • When deciding whether to have sex, what are some things to consider? • What if I decide to wait and someone tries to pressure me into sex? • What is rape? • What are some things I can do to help protect myself against rape? • What is intimate partner violence? • Glossary What happens during puberty? When puberty starts, your brain sends signals to certain parts of the body to start growing and changing. These signals are called hormones. Hormones make your body change and start looking more like an adult’s (see FAQ041 “Your Changing Body—Especially for Teens”). Hormones also can cause emotional changes. What emotional changes occur during puberty? During your teen years, hormones can cause you to have strong feelings, including sexual feelings. You may have these feelings for someone of the other sex or the same sex. Thinking about sex or just wanting to hear or read about sex is normal. It is normal to want to be held and touched by others.