Queer Competencies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

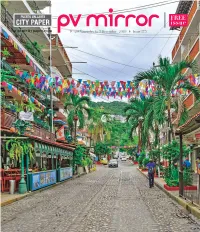

FREE Issue Pvmcitypaper.Com 29 November to 5 December- 2019 Issue 575 2

FREE issue pvmcitypaper.com 29 November to 5 December- 2019 Issue 575 2 250 words max, full name, Publisher / Editor: Graphic Designer: I N D E X : street or e-mail address and/ or tel. number for verification Allyna Vineberg Leo Robby R.R. purposes only. If you do not want your name published, we [email protected] Webmaster: will respect your wishes. Letters Office & Sales: pvmcitypaper.com & articles become the property Online Team An Important Notice: of the PVMIRROR and may be 223.1128 The PVMIRROR wants your views and edited and/or condensed for Cover comments. Please send them by e-mail to: publication. The articles in this Photo: “Olas Altas Street” By Dasan Pillai [email protected] publication are provided for the PV Mirror es una publicación semanal. Certificados purpose of entertainment and Contributors: de licitud de título y contenido en tramite. Prohibida information only. The PV Mirror la reproducción total o parcial de su contenido, City Paper does not accept imágenes y/o fotografías sin previa autorización por Ronnie Bravo / Krystal Frost / Gil Gevins escrito del editor. any responsibility or liability for the content of the articles Giselle Belanger / Stan Gabruk NOTE: on this site or reliance by any To Advertisers & Contributors and those with public person on the site’s contents. Tommy Clarkson / Alex Bourgeau interest announcements, the deadline for publication is: Any reliance placed on such 2:00 pm on Monday of the information is therefore strictly Christie Seeley / John Warren / week prior to publication. at such person’s own risk. Gregg Sutton / Gabriella Namian If you’ve been meaning to find a little information on the region, but never You are here, finally! quite got around to it, we hope that the following will help. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 15/10/2018 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 15/10/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry Someday You'll Want Me To Want You Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Blackout Heartaches I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET Other Side Cheek to Cheek Aren't You Glad You're You 10 Years My Romance (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha No Love No Nothin' 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together Personality Because The Night Kumbaya Sunday, Monday Or Always 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris This Heart Of Mine Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are Mister Meadowlark I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes 1950s Standards The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine Get Me To The Church On Time Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Fly Me To The Moon Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter Crawdad Song Cupid Body And Soul Christmas In Killarney Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze That's Amore 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In Organ Grinder's Swing 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Lullaby Of Birdland Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Rags To Riches Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Something's Gotta Give 1800s Standards I Thought About You I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus (Man -

2018 Marked the Release of the Long-An�Cipated Sophomore Album from Steve Grand, Not the End of Me

About July 6, 2018 marked the release of the long-an:cipated sophomore album from Steve Grand, not the end of me. It hit #2 on the iTunes Pop Chart, #10 on Billboard's Independent Album Chart, and #78 on Billboard’s Top Album Chart. It was released independently on his own label, Grand Na:on LLC. The album includes 12 new tracks, all wriPen and composed by Grand. It also features alternate versions of 3 of the songs. Grand says of the tracks, “This album is autobiographical; very personal, somber and reflec:ve.” “Wri:ng this album was an exercise in catharsis,” says Grand. “I’m more unfiltered on this album and explore some of the internal and external challenges I’ve faced over the last few years.” The album's :tle track, "not the end of me", is a song Grand wrote when a long-:me rela:onship was coming to an end. "Breaking up can be long and drawn-out, painful and ugly. This one certainly was," Grand said. "It was trying and exhaus:ng, (and) this song deals with all of that, as well as the resolu:on that this is 'not the end of me." Grand also predicts "don't let the light in" will be a favorite among his fans. "I wrote it within the last few months before I became sober. At that :me, I was reflec:ng on the way I had been living my life over the last few years that my song 'All-American Boy' blew up, in 2013," he said. -

The Symbolic Annihilation and Recuperation of Queer Identities in Country Music

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2017 Object Of Your Rejection: The Symbolic Annihilation And Recuperation Of Queer Identities In Country Music Lauren Veline University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Veline, Lauren, "Object Of Your Rejection: The Symbolic Annihilation And Recuperation Of Queer Identities In Country Music" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 874. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/874 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OBJECT OF YOUR REJECTION: THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION AND RECUPERATION OF QUEER IDENTITIES IN COUNTRY MUSIC A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Southern Studies The University of Mississippi Lauren Veline May 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Lauren Veline All rights reserved ABSTRACT This thesis addresses the double-marginalization of white queers living in Bible Belt communities by examining the symbolic annihilation of queer identities in country music. Bible Belt queers face unique obstacles and have different needs than queer communities elsewhere due to the cultural context of their communities. The urban-centric (“metronormative”) standards of queer identity and visibility presented in the media do not translate to their lived experiences. Moreover, while white, non-urban southerners possess a source of popular-media expression through country music, queer identities are noticeably absent. The invisibility of Bible Belt queers in the media perpetuates a cycle of hostility and sexual stigma that negatively affects queer individuals, most notably those living in the American South. -

Summer Web 16 Copy

lock3live.com Stage Gates open at 6 pm Concerts start at 7 pm Except July 2, 9 & Aug 13. See below for times. Except July 1 & 8. See below for times. JUN 25 Tony! Toni! Toné! with Rumpelstiltskin $10 Admission MAY 27 Dirty Deeds Extreme AC/DC Tribute with Grunge DNA JUL 2 Slippery When Wet The Ultimate Bon JUN 3 Straight On Heart Tribute Band with Shivering Timbers Jovi Tribute/8:30 p.m. JUN 10 The Stranger A Tribute to Billy Joel with Victory Highway with Electric Mud/6:30 p.m. JUN 17 Absolute Journey The International Tribute to Journey JUL 9 Satisfaction The International Rolling with Karri Fedor & Kerosene Stones Show/8:30 p.m. with JUN 24 Full Moon Fever America’s Premier Tom Petty and Nied’s Hotel Band/6:30 p.m. the Heartbreakers Tribute with The Juke Hounds JUL 16 Robert T The Real Soul Pleaser JUL 1 Bruce in the USA World’s #1 Tribute to Bruce Springsteen & Tribute to James Brown the E Street Band/8:30 p.m. with Vanity Crash/6:30 p.m. with John J Saxx Watkins JUL 8 Hollywood Nights The Ultimate Tribute to Bob Seger/8:30 p.m. JUL 23 Brass Transit The Musical Legacy of with Monica Robbins & The Whiskey Kings/6:30 p.m. Chicago with Charita Franks $5 Admission JUL 15 Aeroforce As a Tribute to Aerosmith with Body Thief JUL 30 Tower of Power with Get On Up JUL 22 Nighttrain The Guns and Roses Tribute Experience $10 Admission with Devilstrip AUG 6 Changes in Latitudes A Tribute to JUL 29 Almost Queen The Ultimate Queen Experience Jimmy Buffet with The JiMiller Band with Chris Allen & The Guilty Hearts AUG 13 Fleetwood Mix A Tribute to Fleetwood AUG 5 Atomic Punks A Tribute to Early Van Halen Mac/8:30 p.m. -

Steve Grand PCT

1042 N. Vista Street #8, West Hollywood, CA 90046 • 323.845.9781 [email protected] • www.kenwerther.com Photo by William Dick. SINGER/SONGWRITER STEVE GRAND The Pink Champagne Tour ONE SHOW ONLY CATALINA JAZZ CLUB IN HOLLYWOOD TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 12 AT 8:30PM —MORE— STEVE GRAND at CATALINA JAZZ CLUB NOVEMBER 12 at 8:30pm [Page 2] Singer/Songwriter Steve Grand is hitting the road this fall with his Pink Champagne Tour and will bring it to Catalina Jazz Club in Hollywood for one show only on Tuesday, November 12, at 8:30pm, it was announced today by Chris Isaacson Presents. The Pink Champagne Tour will feature Grand’s original material as well as some classic covers from some of the most iconic out gay artists of all- time including Queen, Elton John, and George Michael. With over 18 million views on YouTube, a #3 and #10 album on The Billboard Independent Album charts, and one of the most successful music Kickstarter campaigns in history under his belt, Steve Grand has not just broken the rules but has changed the game of how to be a successful singer-songwriter in this era. This past year marked the release of his long- anticipated sophomore album Not the End of Me. Released independently on his own label, Grand Nation LLC, it was greeted by rave reviews from the LGBTQ market. He has been touring nationally and internationally since 2018 gathering new fans, creating energy, and performing new music. Admission is $25–$35, and VIP seating ($50–$60) is available. Online purchases will receive priority seating. -

Steve Grand Broke the Mold for the Traditional Singer-Songwriter

About With over 18 million views on YouTube, a #3 and #10 album on The Billboard Independent A l b u m c h a r t s , a n d o n e o f t h e m o s t successful music Kickstarter campaigns ever under his belt, Grand has not just broken the rules, but has changed the game in how to be a successful singer-songwriter in this era. With the release of his first album, All American Boy, in 2015, Steve Grand broke the mold for the traditional singer-songwriter. Having self-funded a viral video of the title track, then fan funding the release and creating a vocal and energetic fanbase, the openly gay artist from Chicago created a place for himself in the music industry and hasn’t looked back since. Highlights • “Not The End of Me” (New CD debuted July 6, 2018) album hit #2 on iTunes Pop Chart, #10 on Billboard’s Independent Albums Chart & #78 on Billboards Top Albums Chart • Had the #3 Most Funded Music Project in Kickstarter’s History with over 5000 backers • 7M+ view of “All American Boy” video and 17M+ combined views on YouTube • “All American Boy” debuted in 2015 at #47 on the Billboard top 200 and #3 on the Billboard Independent album chart Socials Combined Social Media Following of over 750K+ Facebook: 275K+ Likes Instagram: 242K+ Followers Twitter: 57.3K+ followers YouTube: 190K+ subscribers // 17.4M+ views Highlights Residencies Provincetown, MA - The Art House Previous Pride Events July - September 2017 July - September 2018 • Nashville Pride • Utah Pride Festival • Long Island Pride • Toronto Pride Puerta Vallarta - Red Room Cabaret • Boise Pride • Knoxville Pride Fest December 2017 • • Miami Beach Pride St. -

Steve Grand Talks Touchy-Feely Fans & Moving Beyond 'All-American Boy'

Wedding Expo: Biggest Splash Yet BOYPROBLEMS Steve Grand Talks Touchy-Feely Fans & Moving Beyond ‘All-American Boy’ WWW.PRIDESOURCE.COM MARCH 24, 2016 | VOL. 2412 | FREE 2 BTL | March 24, 2016 www.PrideSource.com ONLINE PHOTOS HAPPENINGS COVER STORY 22 Boy Problems: Steve Grand NEWS Visit #BTLExpo Obama nominates Merrick Garland 4 Trans Day of Visibility has international impact This year was the for SCOTUS position; 6 Couples celebrate LGBT Wedding Expo biggest splash yet SCOTUS nominee has history of 8 Same-Sex Wedding Expo vendors profess passion for LGBTQ community ruling against gay plaintiffs 12 Affirmations to host relationship skills www.BTL WeddingExpo.com See page 14 class 14 Obama nominates Merrick Garland for SCOTUS position 14 SCOTUS nominee has history of ruling CREEP OF THE WEEK SAVE THE DATE VIEWPOINT against gay plaintiffs 18 Michigan Catholic Conference modifies health care coverage 18 Motown Invitational Classic throws bowling rules out the door OPINION 16 Parting Glances 16 Transmissions 17 Creep of the Week: Laurie Higgins Laurie Higgins of the Illinois Family LIFE Institute is one such pearl-clutcher. 24 The Frivolist She, along with the usual anti-LGBT suspects, is encouraging parents to There’s a 26 Happenings pull their kids out of school on DOS Motown Invitational Classic throws 27 Puzzle and comic lest they be indoctrinated with the transgender in my 28 Entertainment equality study released message that it’s not OK to call a bowling rules out the door kid “fag” and push him down the soup 29 Classifieds See page 18 See page 16 stairs after gym. -

Garrett Wang Zoie Palmer Boy & Gurl ...And More! Scan to Read on Mobile Devices Back with Passion Pop

OCTOBER 2013 ® ISSUE 120 • FREE The Voice of Alberta’s LGBT Community Chi Chi LaRue Icon visits Edmonton MICHAEL Kris Holden-Ried URIE Hungry like the Wolf PLUS: Robert Englund Julian Richings Garrett Wang Zoie Palmer Boy & GurL ...and more! Scan to Read on Mobile Devices Back with Passion Pop Business Directory Community Map Events Calendar Tourist Information STARTING ON PAGE 55 Calgary • Alberta • Canada www.gaycalgary.com 2 GayCalgary Magazine #120, October 2013 www.gaycalgary.com Table of Contents OCTOBER 2013 ® 5 Up and Down Alberta Publisher: Steve Polyak Publisher’s Column Editor: Rob Diaz-Marino Sales: Steve Polyak Design & Layout: 8 The Skin I’m In now on DVD Rob Diaz-Marino, AraSteve Shimoon Polyak Broderick Fox’s film launches internationally on iTunes and Amazon Writers and Contributors 10 Cowboys, Armageddon, and the Truth ChrisMercedes Azzopardi, Allen, ChrisP.J. Bremner, Azzopardi, Dave Dallas Brousseau, Barnes, DaveJason Brousseau, Clevett, Andrew Sam Casselman, Collins, Mark Jason Dawson, Clevett, RobAndrew Diaz-Marino, Collins, Emily David-Elijah Collins, Rob Nahmod, Diaz-Marino, Janine 12 Catching Up with Michael Urie EvaJanine Trotta, Eva Trotta,Farley FooJack Foo,Fertig, Marisa Glen Hudson,Hanson, JoanEvan Kayne,Hilty, Evan Stephen Kayne, Lock, Stephen Lisa Lunney, Lock, Neil Steve McMullen, Polyak, Actor talks breaking from Ugly Betty, sexually mysterious new role and RomeoAllan Neuwirth, San Vicente Steve and Polyak, the LGBT Carey Community Rutherford, of 12 PAGE RomeoCalgary, San Vicente, Edmonton, Ed Sikov, -

Go Purple for Spirit Day and Take a Stand Against Bullying by Bill Pritchard October 17, 2013

ChicagoPride.com News October 17, 2013 Go Purple for Spirit Day and take a stand against bullying By Bill Pritchard October 17, 2013 https://chicago.gopride.com/news/article.cfm/articleid/48336916 Millions of people today are "going purple" for Spirit Day, an annual day in October when Americans wear purple to speak out against bullying and to show their support for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning (LGBTQ) youth. The idea for Spirit Day came in 2010, from teenager Brittany McMillan, who wanted to remember those young people who lost their lives to suicide and to take a stand against bullying. "Going purple" involves wearing purple, as well as turning logos and other social media badges purple to stand against bullying. Spirit Day is promoted each year by the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD), which recruits hundreds of celebrities, entertainment organizations, brands, landmarks, sports leagues, faith groups, school districts, colleges and universities for the campaign. "As our country moves closer to full legal equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people, LGBT youth continue to face staggering rates of bullying at school," GLAAD spokesman Wilson Cruz said. "Spirit Day is an opportunity for all of us to send a message of support to LGBT youth everywhere and for those young people to hold their heads high while our nation stands behind them." This year's ambassadors include transgender athlete Kye Allums, out basketball players Jason Collins and Brittney Griner and out WWE superstar Darren Young. Viewers of "Access Hollywood," "CNBC," "Extra, Jimmy Kimmel Live," "MSNBC," "Telemundo," "The Talk," "The View," "Watch What Happens Live," the "Wendy Williams Show" and more will notice a lot of purple in the hosts' clothing. -

Gay Country Song 'All American Boy' Goes Viral on Youtube by Ron Matthew Inawat July 4, 2013

ChicagoPride.com News July 4, 2013 Gay country song 'All American Boy' goes viral on YouTube By Ron Matthew Inawat July 4, 2013 https://chicago.gopride.com/news/article.cfm/articleid/43650000 CHICAGO, IL -- Earlier this week, Steve Grand released his first single - on his own through the social network community - a country song titled "All American Boy" that has garnered nearly 430,000 views on Youtube in its first four days. On his Facebook page, the Chicago-native writes, "time to be brave. the world does not see change until it sees honesty. I am taking a risk here in many ways, but really there is no choice but to be brave. To not tell this story is to let my soul die. It is all I believe in. It is all I hold dear. We have all longed for someone we can never have...we all have felt that ache for our #allamericanboy." In the country-rock ballad, Grand's touching and brave lyrics describe an unrequited love. The chorus, which tied into the holiday week release goes, "be my All-American boy tonight where everyday's the 4th of July." Grand has already been dubbed the "First Gay Male Country Star" by BuzzFeed. The artist continues on his page, "If my story makes even a couple people feel less alone in their aching, all the blood, sweat, tears, and soul I put into this project makes it worth it. Thanks for watching." Steve Grand, who changed his name from Steve Starchild on July 2nd for the release of his first original song, told fans, "After today, Steve Starchild will no longer be. -

July 20, 2018 | Volume XVI, Issue 6

July 20, 2018 | Volume XVI, Issue 6 By BIll reDmOnD-palmer Last month, computer engineer and busi- First Trans Candidate vention floor vote to nominate and then ness executive Sharon Brackett became elect the first black governor of Boys State the first trans woman to be elected to an New York. Since then I was hooked. Elec- official office in a contested election in to Win Contested MD Race Reflects tion night with my kids was always like a Maryland. Brackett prevailed in a prima- tween Buffalo and Rochester. I had a good since 1990! This is home. I can’t think of holiday. We would color in maps, ry against 14 other candidates. She was middle-class childhood. Mom was a nurse, another place to be. á la Tim Russert, in front of elected to the District 46 Democratic Cen- and dad was a haberdasher. We did not how did you get interested the TV for presidential tral Committee, representing the Baltimore have a lot but we never really “wanted” for in politics? elections. Later when neighborhoods of Canton, Locust Point, anything either. I went to college In 1978, while it came time to get Federal Hill, Brooklyn, Curtis Bay, and at Syracuse University where I still in high school, some non-discrim- Cherry Hill. She placed third out of 15 can- studied computer engineering. Af- An I attended the ination legislation didates in her very first run for office. ter college I had a number of jobs interview American Le- passed in Mary- I’ve known and respected Sharon for in various companies but almost gion’s Boys State land my interest many years and appreciated the opportu- always found myself in charge of with Sharon of New York.