Opinion Is Subject to Correction Before Publication in the PACIFIC REPORTER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

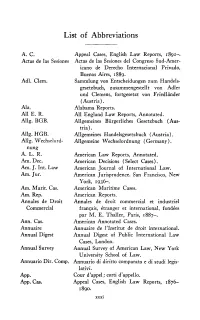

List of Abbreviations

List of Abbreviations A. C. Appeal Cases, English Law Reports, r8gr-. Aetas de las Sesiones Aetas de las Sesiones del Congreso Sud-Amer icano de Derecho Internacional Privado, Buenos Aires, r88g. Adl. Clem. Sammlung von Entscheidungen zum Handels gesetzbuch, zusammengestellt von Adler und Clemens, fortgesetzt von Friedlander (Austria). Ala. Alabama Reports. All E. R. All England Law Reports, Annotated. Allg. BGB. Allgemeines Biirgerliches Gesetzbuch (Aus- tria). Allg. HGB. Allgemeines Handelsgesetzbuch (Austria). All g. W echselord- Allgemeine Wechselordnung (Germany). nung A. L. R. American Law Reports, Annotated. Am. Dec. American Decisions ( Select Cases) . Am. J. Int. Law American Journal of International Law. Am. Jur. American Jurisprudence. San Francisco, New York, 1936-. Am. Marit. Cas. American Maritime Cases. Am. Rep. American Reports. Annales de Droit Annales de droit commercial et industriel Commercial fran~ais, etranger et international, fondees par M. E. Thaller, Paris, r887-. Ann. Cas. American Annotated Cases. Annuaire Annuaire de l'Institut de droit international. Annual Digest Annual Digest of Public International Law Cases, London. Annual Survey Annual Survey of American Law, New York University School of Law. Annuario Dir. Camp. Annuario di diritto comparato e di studi legis lativi. App. Cour d'appel; corti d'appello. App. Cas. Appeal Cases, English Law Reports, 1876- r8go. xxxi XXXll LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS App. D.C. Appeal Cases, District of Columbia. App. Div. New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division Reports. Arch. Civ. Prax. Archiv fiir die civilistische Praxis (Germany) . Arch. Jud. Archivo judiciario (Brazil). Ariz. Arizona Reports. Ark. Arkansas Reports. Asp. Marit. Cas. Aspinall's Maritime Cases. Atl. Atlantic Reporter, National Reporter System (United States). -

Research Guide

Research Guide FINDING CASES I. HOW TO FIND A CASE WHEN YOU KNOW THE CITATION A. DECIPHERING LEGAL CITATIONS 1. CASE CITATIONS A case citation includes: the names of the parties, the volume number of the case reporter, the abbreviated name of the reporter, the page number where the case can be found, and the year of the decision. EXAMPLE: Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta, 30 Cal.3d 800 (1982). Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta = names of the parties 30 = volume number of the case reporter Cal. = abbreviated name of the case reporter, California Reports 3d = series number of the case reporter, California Reports 800 = page number of the case reporter (1982) = year of the decision 2. ABBREVIATIONS OF REPORTER NAMES The abbreviations used in citations can be deciphered by consulting: a. Prince’s Bieber Dictionary of Legal Abbreviations, 6th ed. (Ref. KF 246 .p74 2009) b. Black's Law Dictionary (Ref. KF 156 .B624 2009). This legal dictionary contains a table of abbreviations. Copies of Black's are located on dictionary stands throughout the library, as well as in the Reference Collection. 3. REPORTERS AND PARALLEL CITATIONS A case may be published in more than one reporter. Parallel citations indicate the different reporters publishing the same case. EXAMPLE: Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta, 30 Cal.3d 800, 180 Cal. Rptr. 628, 640 P.2d 764 (1982). 02/08/12 (Rev.) RG14 (OVER) This case will be found in three places: the "official" California Reports 3d (30 Cal. 3rd 800); and the two "unofficial" West reporters: the California Reporter (180 Cal. -

Abandoning Law Reports for Official Digital Case Law Peter W

Cornell Law Library Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository Cornell Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship Spring 2011 Abandoning Law Reports for Official Digital Case Law Peter W. Martin Cornell Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub Part of the Courts Commons, Legal Writing and Research Commons, and the Science and Technology Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Peter W., "Abandoning Law Reports for Official Digital Case Law" (2011). Cornell Law Faculty Publications. Paper 1197. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub/1197 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE JOURNAL OF APPELLATE PRACTICE AND PROCESS ARTICLES ABANDONING LAW REPORTS FOR OFFICIAL DIGITAL CASE LAW* Peter W. Martin** I. INTRODUCTION Like most states Arkansas entered the twentieth century with the responsibility for case law publication imposed by law on a public official lodged within the judicial branch. The "reporter's" office was then, as it is still today, a "constitutional" one.' Title and role reach all the way back to Arkansas's * Q Peter W. Martin, 2011. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 543 Howard Street, 5th Floor, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. -

How to Locate a Case Using a Digest

Sacramento County Public Law Library 609 9th St. Sacramento, CA 95814 saclaw.org (916) 874-6012 >> Home >> Law 101 DIGESTS How to Locate a Case Using a Digest The Law Library has two sets of West Digests in print format (now published by Thomson Reuters): Table of Contents The United States Supreme Court Digest, used to locate 1. How to Locate a Case Using United States Supreme Court cases, is located in Compact Topic and Key Number System in Shelving next to the Supreme Court Reporter, at KF 101 .1 Westlaw ...................................... 2 U55. Like all digests, each volume in the set is updated 2. Abbreviations and Locations of with pocket parts. Case Reporters ............................ 4 West’s California Digest, located in Row C-9 of Compact Shelving at KFC 57 .W47, is used to locate California Supreme Court and California Appellate Court cases. Digests are arranged alphabetically by topic. Examples of the approximately 400 topics are: Banks and Banking, Franchises, Insurance, Libel and Slander, Partnership, Fraud, and Criminal Law. Each topic is divided into subtopics known as "key numbers." A complete list of topic headings is available in the front of each digest volume. A complete list of key numbers is available at the beginning of each topic. A Quick Reference Guide to West Key Number System is available online west.thomson.com/documentation/westlaw/wlawdoc/wlres/keynmb06.pdf. Locate a topic and key number that interests you by scanning the list of topic headings and key numbers or by using the Descriptive Word Index at the end of each set of digests. -

Appellate Law Update Presentation

Appellate Law Update April 19, 2018 M. Anne Kelly, Division Director Criminal Appeals Division • §8‐5‐2. Duties of • Except as otherwise attorney general provided by law, the attorney general shall: • A. prosecute and defend all causes in the supreme court and court of appeals in which the state is a party or interested; • Jane Bernstein – (505) 717‐3509 • John Kloss – (505) 717‐3592 • [email protected] • [email protected] • Laurie Blevins – (505) 717‐3590 • Mark Lovato – (505) 717‐3541 • [email protected] • [email protected] • Anita Carlson – (505) 490‐4060 • Eran Sharon – (505) 490‐4860 • [email protected] • [email protected] • Meryl Francolini – (505) 717‐3591 • Emily Tyson‐Jorgenson – (505) 490‐4868 • [email protected] • etyson‐[email protected] • Charles Gutierrez – (505) 717‐3522 • Maris Veidemanis – (505) 490‐4867 • [email protected] • [email protected] • Marko Hananel – (505) 490‐4890 • Victoria Wilson – (505) 717‐3574 • [email protected] • [email protected] • Walter Hart – (505) 717‐717‐3523 • Lauren Wolongevicz – (505) 3562 • [email protected] • [email protected] • Maha Khoury – (505) 490‐4844 • John Woykovsky – (505) 717‐3576 • [email protected] • [email protected] • Claire Welch • Rose Leal • [email protected] • [email protected] • (505) 717‐3573 • (505) 490‐4848 • Handles state and • Handles direct appeal federal habeas matters matters • “A petition for writ of certiorari . or a Supreme Court order granting the petition does not affect the precedential value of an opinion of the Court of Appeals, unless otherwise ordered -

Loislaw Case Coverage Federal Reporters

Loislaw Case Coverage Loislaw includes comprehensive coverage of cases and associated citations for the reporters and date ranges listed here (except as noted for the F. Supp and B.R. reporters) and select coverage of cases and associated citations for unofficial reporters not listed here or reporters outside of the date ranges we cover. Jurisdiction Court Reporter Citation Style Date Range Volumes Status Federal Reporters U.S. U.S. Supreme Court U.S. Reports U.S. 1754-present 1-present Official Supreme Court Reporter S.Ct. 1935-present 55-present Unofficial U.S. 1st Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F 3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 4th Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F 2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 6th Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 7th Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. -

FOR PUBLICATION in WEST's HAWAI#I REPORTS and PACIFIC REPORTER in the INTERMEDIATE COURT of APPEALS of the STATE of HAWAI#I ---O

FOR PUBLICATION IN WEST'S HAWAI#I REPORTS AND PACIFIC REPORTER Electronically Filed Intermediate Court of Appeals CAAP-17-0000696 30-JUN-2021 09:52 AM Dkt. 92 OP IN THE INTERMEDIATE COURT OF APPEALS OF THE STATE OF HAWAI#I ---o0o--- MJ, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. CR, Defendant-Appellant and CHILD SUPPORT ENFORCEMENT AGENCY, STATE OF HAWAI#I, Defendant. NO. CAAP-17-0000696 APPEAL FROM THE FAMILY COURT OF THE FIRST CIRCUIT (FC-P NO. 16-1-6470) June 30, 2021 GINOZA, CHIEF JUDGE, LEONARD AND HIRAOKA, JJ. OPINION OF THE COURT BY GINOZA, CHIEF JUDGE Defendant-Appellant CR (Father) appeals from (1) the "Order" (Temporary Order), filed on January 26, 2017, in favor of Plaintiff-Appellee MJ (Mother); and (2) the "Decision and Order" (Decision) filed September 1, 2017, by the Family Court of the First Circuit (Family Court).1 1 The Honorable R. Mark Browning entered the Temporary Order. The Honorable Catherine H. Remigio presided over the trial held on June 14, 2017, and entered the Decision. FOR PUBLICATION IN WEST'S HAWAI#I REPORTS AND PACIFIC REPORTER On appeal, Father contends the Family Court erred in its Temporary Order and its Decision because: (1) it lacked subject matter jurisdiction with respect to the "Petition for Paternity" (Petition) filed by Mother in this matter;2 and (2) it lacked personal jurisdiction over Father for purposes of determining parentage or ordering child support and monetary obligations with respect to Father and Mother's minor child (Child). Father asserts the Family Court violated his rights to due process by not allowing him to argue the issue of personal jurisdiction at trial. -

California Style Manual

CALIFORNIA STYLE MANUAL Fourth Edition A HANDBOOK OF LEGAL STYLE FOR CALIFORNIA COURTS AND LAWYERS By Edward W. Jessen Reporter of Decisions for the Supreme Court and Courts of Appeal .W4-23370-9 ©1942, 1961, 1977, 1986,2000 by the Supreme Court of California Page composition by Imagelnk, San Francisco Cover design by Side by Side Designs, San Francisco Editiorial preparation and manufacturing West Group, California's Official Legal Publisher FOREWORD For almost 60 years, the legal community of California has benefited from the publication of the California Style Manual. The manual provides a guide to standard legal style in the appellate courts, and benefits litigants and jurists alike by establishing a common stylistic base that permits read- ers to focus readily on substance rather than form. In the 14 years since publication of the third edition of the Style Manual, much has changed in the processes used for creating legal docu- ments. A personal computer on the desk is now the rule rather than the exception for most lawyers and judges. At the same time, the availability of diverse reference resources has expanded the ease and scope of research. This latest revision of the manual reflects and responds to many of the changes that the legal profession has experienced, while maintaining a steady hold on the practices that have served the courts and the profession so well. I extend my appreciation to the Reporter of Decisions and those who have assisted him in the task of revising this valuable reference tool. Ronald M. George Chief Justice of California iii SUPREME COURT APPROVAL To the Reporter of Decisions: Pursuant to the authority conferred on the Supreme Court of Cali- fornia by Government Code section 68902, the California Style Manual, Fourth Edition, as submitted to this court for review is approved and adopted as the official organ for the styles to be used in the publication of the Official Reports. -

256 Alaska 982 PACIFIC REPORTER, 2D SERIES

256 Alaska 982 PACIFIC REPORTER, 2d SERIES 60(b)(6).21 Rather, we view them ‘‘as instan- claim to a portion of the proceeds. The tiations of the equitable factors required to record is devoid of any evidence or argument overcome the principle that, at some point, regarding the life insurance policies. There- ‘litigation [must] be brought to an end.’ ’’ 22 fore, we conclude that it was premature to Camille’s claim for relief met the standards rule on this issue and we vacate this ruling. for relief under Rule 60(b)(6), because her eligibility for the survivorship benefits was IV. CONCLUSION one of the fundamental assumptions underly- We AFFIRM the superior court’s holding ing the property division. We therefore hold that it lacks jurisdiction to enforce the prop- that Camille is entitled to relief under Rule erty settlement agreement. But we RE- 60(b)(6). VERSE the denial of Rule 60(b)(6) relief to Camille and REMAND for proceedings con- C. Equity Demands that Camille Receive sistent with this opinion. We VACATE the Half of the Value of the Marital Por- order regarding Camille’s claim to the insur- tion of William’s Civil Service Pen- ance proceeds. sion. [17] Because we hold that the parties agreed to divide William’s civil service pen- , sion we conclude that Camille should receive one-half of the value of the marital portion of William’s civil service pension—valued as of the date the parties entered into the proper- ty settlement agreement, August 12, 1992. A.A., Appellant, This is the most equitable result given the particular facts of this case. -

INTRODUCTION SUPREME POWER SUPREME LAW the WE the PEOPLE LEGAL PRIMER HOLISTIC VISION Democracy Means a Form of Government Law Differs from Power

WE THE PEOPLE LEGAL PRIMER Forms Of Address And Salutations ...................................... 67 The Constitution Of The United States Of America ............. 2 English Grammar And Usage ............................................... 68 Amendments To The Constitution ......................................... 5 Your Health And Your Freedom .......................................... 70 The Bill Of Rights For Criminal Defendants ......................... 7 The Strangest Secret In The World ...................................... 71 An Overview Of State Constitutions...................................... 7 Desiderata ............................................................................. 71 Interpretations Of The Constitution ....................................... 7 The History Of Law ............................................................... 8 ADDITIONAL LEGAL INFORMATION ........................... 72 Speeches And Other Writings ...............................................11 Protecting Your Rights In Prison: ........................................... 72 The American Republic: Division Of Power ........................12 After Your Release ................................................................ 73 Basic Judicial Doctrines ........................................................12 The Structure Of The Federal Judiciary ................................12 NATIONAL PRISONER RESOURCE LIST ..................... 73 The Jurisdiction Of The Federal Judiciary ............................13 Artists & Writers In Prison -

Finding Federal & State Cases

Finding Federal and State Cases University of Idaho College of Law Reporters Court opinions, or cases, are published in books called reporters. Reporters are sets of books collecting cases in chronological order. 1. Official and Unofficial Reporters A. Reporters include official and unofficial versions. B. The text of the opinion in official and unofficial reporters is identical. C. Unofficial reporters include editorial additions to aid in research. D. Official versions must be used for citations in court documents. 2. Jurisdiction Coverage A. Some reporters limit opinions to a single jurisdiction or court. B. Some reporters collect cases from multiple jurisdictions. 3. Examples 1. Single jurisdiction: Idaho Reports publishes cases from the Court of Appeals and Supreme Court in Idaho only. 2. Multiple jurisdictions: the Pacific Reporter provides state cases from Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Oregon, Utah, Washington & Wyoming. Citation Format The basic citation format for all reporters includes the names of the parties to the case followed by the volume number, abbreviated name of the reporter, page number of the reporter in which the opinion is published and the year of the decision. Jurisdiction information is added for the Federal Reporters and Federal Supplements. Example: Citation for U.S. Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education Citation: Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) Names of Parties Volume Reporter Page Date Brown v. Board of Education 347 U.S. 483 1954 1 Supreme Court Reporters 1. Three reporters each publish all United States Supreme Court decisions: A. United States Reports (U.S.) B. -

Disciplinary Summary

Disciplinary Summary The following compilation of disciplinary action taken by the Board of Professional Responsibility collects cases arising since 2002, along with some earlier cases published in Pacific Reporter. For cases of public discipline that were not published in Pacific Reporter, a citation to the Wyoming Supreme Court docket number is provided. The disciplinary summary is intended as a useful guide to aid Wyoming practitioners as they encounter situations in which one or more of the provisions of the Wyoming Rules of Professional Conduct may be implicated. The summaries provided are just that – summaries – and do not purport to be an exhaustive presentation of the facts supporting or the reasons applied to a particular disciplinary action. Updated November 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Rule 1.1. Competence ................................................................................................................................ 1 Rule 1.2. Scope of Representation and Allocation of Authority Between Client and Lawyer ............ 5 Rule 1.3. Diligence ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Rule 1.4. Communication ........................................................................................................................ 14 Rule 1.5. Fees ............................................................................................................................................ 20 Rule 1.6. Confidentiality of Information