The United States and the Macrosecuritisation of the “China Threat”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press Releases, Speeches, Correspondences and Radio Transcripts

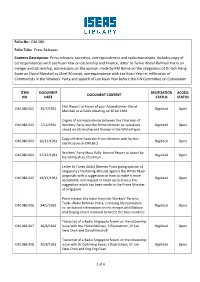

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press releases, speeches, correspondences and radio transcripts. Includes copy of correspondences with Lee Kuan Yew on citizenship and finance, letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra on merger and citizenship, submissions on the opinion made by KM Byrne on the allegations of Dr Goh Keng Swee on David Marshall as Chief Minister, correspondence with Lee Kuan Yew re: infiltration of Communists in the Workers' Party and speech of Lee Kuan Yew before the UN Committee on Colonialism ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS First Report to Anson of your Assemblyman David DM.086.001 30/7/1961 Digitized Open Marshall at a Public Meeting on 30 Jul 1961 Copies of correspondence between the Chairman of DM.086.002 7/12/1961 Workers' Party and the Prime Minister re: questions Digitized Open raised on citizenship and finance in the White Paper Copy of letter from the Prime Minister with further DM.086.003 16/12/1961 Digitized Open clarification on DM.86.2 Workers' Party Mass Rally: Second Report to Anson by DM.086.004 17/12/1961 Digitized Open David Marshall, Chairman Letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra giving opinion of Singapore's hardening attitude against the White Paper proposals with a suggestion on how to make it more DM.086.005 19/12/1961 Digitized Open acceptable, and request to meet up to discuss this suggestion which has been made to the Prime Minister of Singapore Press release of a letter from the Workers' Party to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra, enclosing -

Pengembangan Game 3D Warship Operation Trikora

Jurnal Pengembangan Teknologi Informasi dan Ilmu Komputer e-ISSN: 2548-964X Vol. 1, No. 12, Desember 2017, hlm. 1875-1882 http://j-ptiik.ub.ac.id Pengembangan Game 3D Warship Operation Trikora Mohamad Faisal Amir1, Wibisono Sukmo Wardhono2, Issa Arwani3 Program Studi Teknik Informatika, Fakultas Ilmu Komputer, Universitas Brawijaya Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstrak Banyak kisah-kisah operasi Trikora hanya tersimpan dalam museum sejarah. Sehingga banyak yang tidak mengetahui pertikaian senjata dan perjuangan heroik yang terjadi dalam operasi tersebut. Video game adalah cara yang menarik untuk mengenalkan cerita Operasi Trikora maka dibuatlah game Warship Operation Trikora. Pengembangan game adalah proses membuat konten dan aturan permainan. Terdapat metode proses iterative dalam pengembangan game yaitu membuat prototipe, dimainkan, dan disempurnakan terus berulang kali sebelum dianggap final. Grafis 3D menjadi sarana untuk mencapai generasi dunia fiksi dalam imajinasi pemain yang tumbuh dari pemahaman representasi 3D sehingga membentuk permainan yang immersive. Untuk membangun permainan yang naratif maka game dirancang dengan membuat skenario cerita pertempuran berupa step-step yang terdiri dari kumpulan event dalam permainan. Dari skenario cerita pertempuran terdapat objektif yaitu event yang berupa tugas untuk pemain. Berdasarkan tugasnya objektif dapat dikelompokkan menjadi 5 tipe yaitu lingkup area, pointer lokasi, menyerang kapal, menyerang pesawat, menyerang pillbox. Metode Iterative design digunakaan untuk menguji objektif apabila diterapkan dalam permainan dengan cara membuat rapid prototipe, melakukan playtest, dan melakukan revisi. Aktivitas tersebut dilakukan berulang kali sampai permainan dianggap layak diimplementasikan. Implementasi karakter 3D dibutuhkan agar tercipta asset karakter-karakter yang terlibat dalam skenario cerita pertempuran yaitu terdapat 7 tipe karakter berupa kapal, pesawat, dan pillbox. -

Remembering Dr Goh Keng Swee by Kwa Chong Guan (1918–2010) Head of External Programmes S

4 Spotlight Remembering Dr Goh Keng Swee By Kwa Chong Guan (1918–2010) Head of External Programmes S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Nanyang Technological University Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong declared in his eulogy at other public figures in Britain, the United States or China, the state funeral for Dr Goh Keng Swee that “Dr Goh was Dr Goh left no memoirs. However, contained within his one of our nation’s founding fathers.… A whole generation speeches and interviews are insights into how he wished of Singaporeans has grown up enjoying the fruits of growth to be remembered. and prosperity, because one of our ablest sons decided to The deepest recollections about Dr Goh must be the fight for Singapore’s independence, progress and future.” personal memories of those who had the opportunity to How do we remember a founding father of a nation? Dr interact with him. At the core of these select few are Goh Keng Swee left a lasting impression on everyone he the members of his immediate and extended family. encountered. But more importantly, he changed the lives of many who worked alongside him and in his public career initiated policies that have fundamentally shaped the destiny of Singapore. Our primary memories of Dr Goh will be through an awareness and understanding of the post-World War II anti-colonialist and nationalist struggle for independence in which Dr Goh played a key, if backstage, role until 1959. Thereafter, Dr Goh is remembered as the country’s economic and social architect as well as its defence strategist and one of Lee Kuan Yew’s ablest and most trusted lieutenants in our narrating of what has come to be recognised as “The Singapore Story”. -

28. Rights Defense and New Citizen's Movement

JOBNAME: EE10 Biddulph PAGE: 1 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Fri May 10 14:09:18 2019 28. Rights defense and new citizen’s movement Teng Biao 28.1 THE RISE OF THE RIGHTS DEFENSE MOVEMENT The ‘Rights Defense Movement’ (weiquan yundong) emerged in the early 2000s as a new focus of the Chinese democracy movement, succeeding the Xidan Democracy Wall movement of the late 1970s and the Tiananmen Democracy movement of 1989. It is a social movement ‘involving all social strata throughout the country and covering every aspect of human rights’ (Feng Chongyi 2009, p. 151), one in which Chinese citizens assert their constitutional and legal rights through lawful means and within the legal framework of the country. As Benney (2013, p. 12) notes, the term ‘weiquan’is used by different people to refer to different things in different contexts. Although Chinese rights defense lawyers have played a key role in defining and providing leadership to this emerging weiquan movement (Carnes 2006; Pils 2016), numerous non-lawyer activists and organizations are also involved in it. The discourse and activities of ‘rights defense’ (weiquan) originated in the 1990s, when some citizens began using the law to defend consumer rights. The 1990s also saw the early development of rural anti-tax movements, labor rights campaigns, women’s rights campaigns and an environmental movement. However, in a narrow sense as well as from a historical perspective, the term weiquan movement only refers to the rights campaigns that emerged after the Sun Zhigang incident in 2003 (Zhu Han 2016, pp. 55, 60). The Sun Zhigang incident not only marks the beginning of the rights defense movement; it also can be seen as one of its few successes. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 2007 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–026 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIM WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. -

Black-Jewish Coalition” Unraveled: Where Does Israel Fit?

The “Black-Jewish Coalition” Unraveled: Where Does Israel Fit? A Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Hornstein Jewish Professional Leadership Program Professors Ellen Smith and Jonathan Krasner Ph.D., Advisors In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Leah Robbins May 2020 Copyright by Leah Robbins 2020 Acknowledgements This thesis was made possible by the generous and thoughtful guidance of my two advisors, Professors Ellen Smith and Jonathan Krasner. Their content expertise, ongoing encouragement, and loving pushback were invaluable to the work. This research topic is complex for the Jewish community and often wrought with pain. My advisors never once questioned my intentions, my integrity as a researcher, or my clear and undeniable commitment to the Jewish people of the past, present, and future. I do not take for granted this gift of trust, which bolstered the work I’m so proud to share. I am also grateful to the entire Hornstein community for making room for me to show up in my fullness, and for saying “yes” to authentically wrestle with my ideas along the way. It’s been a great privilege to stretch and grow alongside you, and I look forward to continuing to shape one another in the years to come. iii ABSTRACT The “Black-Jewish Coalition” Unraveled: Where Does Israel Fit? A thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Leah Robbins Fascination with the famed “Black-Jewish coalition” in the United States, whether real or imaginary, is hardly a new phenomenon of academic interest. -

INDIANA MAGAZINE of HISTORY Volume LI JUNE,1955 Number 2

INDIANA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY Volume LI JUNE,1955 Number 2 Hoosier Senior Naval Officers in World War I1 John B. Heffermn* Indiana furnished an exceptional number of senior of- ficers to the United States Navy in World War 11, and her sons were in the very forefront of the nation’s battles, as casualty lists and other records testify. The official sum- mary of casualties of World War I1 for the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard, covering officers and men, shows for Indiana 1,467 killed or died of wounds resulting from combat, 32 others died in prison camps, 2,050 wounded, and 94 released prisoners of war. There were in the Navy from Indiana 9,412 officers (of this number, probably about 6 per- cent or 555 were officers of the Regular Navy, about 10 per- cent or 894 were temporary officers promoted from enlisted grades of the Regular Navy, and about 85 percent or 7,963 were Reserve officers) and 93,219 enlisted men, or a total of 102,631. In the Marine Corps a total of 15,360 officers and men were from Indiana, while the Coast Guard had 229 offic- ers and 3,556 enlisted men, for a total of 3,785 Hoosiers. Thus, the overall Indiana total for Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard was 121,776. By way of comparison, there were about 258,870 Hoosiers in the Army.l There is nothing remarkable about the totals and Indiana’s representation in the Navy was not exceptional in quantity; but it was extraordinary in quality. -

Konfrontasi: 1963

BACKGROUND & MECHANICS GUIDE KONFRONTASI: 1963 2 BACKGROUND GUIDE WELCOME FROM THE DIAS Hello Delegates, My name is Yue Ting Kong, and welcome to the SSICsim 2019 JCC, Konfrontasi. Set during the Cold War in Southeast Asia, where Indonesia and the Commonwealth were in a quasi-war over the fate of the unification of Malaysia. In this committee you will encounter counter-insurgency tactics, guerrilla warfare and terrorism. However, you’ll also see the issues brought forth by the Race Riots that took place in Malaysia during its federation and the divide between communists and the non-aligned movements in Indonesia. This two-faced committee will explore an area of the world going through nationalism, decolonization and the Cold War, hoping to advance your nations by achieving a balance between political manoeuvring and military force. History has largely forgotten this conflict and its surrounding events which helped shape the world we live in today. This conflict led to the formation of the Association of Southeast Asian States (ASEAN), and fermented the independence of Malaysia in the international community. The Race Riots that occurred during the war led the independence of Singapore under Lee Kwan Yew and its evolution into a strong Asian Tiger. In Indonesia, it led to the collapse of an increasingly communist regime and the creation of a country who would become incredibly important to the non-aligned movement. A bit of background on myself, I’m a Second Year History Specialist at the University of Toronto and this will be my 7th year doing Model United Nations. Best of luck delegates and I look forward to meeting you all at the conference. -

Contributors.Indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM F-479 /203/BER00069/Work/Indd/%20Backmatter

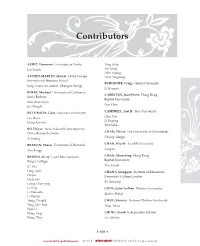

02_Contributors.indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM f-479 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter Contributors AUBIÉ, Hermann University of Turku Yang Jiang Liu Xiaobo Yao Ming Zhao Ziyang AUSTIN-MARTIN, Marcel China Europe Zhou Youguang International Business School BURGDOFF, Craig Capital University Jiang Zemin (co-author: Zhengxu Wang) Li Hongzhi BERRY, Michael University of California, CABESTAN, Jean-Pierre Hong Kong Santa Barbara Baptist University Hou Hsiao-hsien Lien Chan Jia Zhangke CAMPBELL, Joel R. Troy University BETTINSON, Gary Lancaster University Chen Yun Lee, Bruce Li Keqiang Wong Kar-wai Wen Jiabao BO Zhiyue New Zealand Contemporary CHAN, Felicia The University of Manchester China Research Centre Cheung, Maggie Xi Jinping BRESLIN, Shaun University of Warwick CHAN, Hiu M. Cardiff University Zhu Rongji Gong Li BROWN, Kerry Lau China Institute, CHAN, Shun-hing Hong Kong King’s College Baptist University Bo Yibo Zen, Joseph Fang Lizhi CHANG Xiangqun Institute of Education, Hu Jia University College London Hu Jintao Fei Xiaotong Leung Chun-ying Li Peng CHEN, Julie Yu-Wen Palacky University Li Xiannian Kadeer, Rebiya Li Xiaolin Tsang, Donald CHEN, Szu-wei National Taiwan University Tung Chee-hwa Teng, Teresa Wan Li Wang Yang CHING, Frank Independent Scholar Wang Zhen Lee, Martin • 569 • www.berkshirepublishing.com © 2015 Berkshire Publishing grouP, all rights reserved. 02_Contributors.indd Page 570 9/22/15 12:09 PM f-500 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter • Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography • Volume 4 • COHEN, Jerome A. New -

Report of the Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman Or Degrading Treatment Or Punishment, Juan E

United Nations A/HRC/22/53/Add.4 General Assembly Distr.: General 12 March 2013 English/French/Spanish only Human Rights Council Twenty-second session Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Juan E. Méndez Addendum Observations on communications transmitted to Governments and replies received* * The present document is being circulated in the languages of submission only. GE.13-11820 A/HRC/22/53/Add.4 Contents Paragraphs Page Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................... 5 I. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1–5 6 II. Observations by the Special Rapporteur ................................................................. 6–162 6 Angola ................................................................................................................ 6 6 Argentina ................................................................................................................ 7 7 Azerbajan ................................................................................................................ 8–9 7 Bahrain ................................................................................................................ 10–14 8 Bangladesh -

Americanlegionvo1356amer.Pdf (9.111Mb)

Executive Dres WINTER SLACKS -|Q95* i JK_ J-^ pair GOOD LOOKING ... and WARM ! Shovel your driveway on a bitter cold morning, then drive straight to the office! Haband's impeccably tailored dress slacks do it all thanks to these great features: • The same permanent press gabardine polyester as our regular Dress Slacks. • 1 00% preshrunk cotton flannel lining throughout. Stitched in to stay put! • Two button-thru security back pockets! • Razor sharp crease and hemmed bottoms! • Extra comfortable gentlemen's full cut! • 1 00% home machine wash & dry easy care! Feel TOASTY WARM and COMFORTABLE! A quality Haband import Order today! Flannel 1 i 95* 1( 2 for 39.50 3 for .59.00 I 194 for 78. .50 I Haband 100 Fairview Ave. Prospect Park, NJ 07530 Send REGULAR WAISTS 30 32 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 pairs •BIG MEN'S ADD $2.50 per pair for 46 48 50 52 54 INSEAMS S( 27-28 M( 29-30) L( 31-32) XL( 33-34) of pants ) I enclose WHAT WHAT HOW 7A9.0FL SIZE? INSEAM7 MANY? c GREY purchase price D BLACK plus $2.95 E BROWN postage and J SLATE handling. Check Enclosed a VISA CARD# Name Mail Address Apt. #_ City State .Zip_ 00% Satisfaction Guaranteed or Full Refund of Purchase $ § 3 Price at Any Time! The Magazine for a Strong America Vol. 135, No. 6 December 1993 ARTICLE s VA CAN'T SURVIVE BY STANDING STILL National Commander Thiesen tells Congress that VA will have to compete under the President's health-care plan. -

The Impact of the Cold War and the Second Red Scare on the 1952 American Presidential Election

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Online Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship January 2019 The Impact of the Cold War and the Second Red Scare on the 1952 American Presidential Election Dana C. Johns Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/etd Part of the Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Johns, Dana C., "The Impact of the Cold War and the Second Red Scare on the 1952 American Presidential Election" (2019). Online Theses and Dissertations. 594. https://encompass.eku.edu/etd/594 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Online Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In thispresenting thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Master of Arts degree at Eastern Kentucky University, I agree that the Library shall make it available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this document are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgements of the source are made. Permission for extensive quotation from or reproduction of this document may be granted by my major professor. In [his/her] absence, by the Head oflnterlibrary Services when, in the opinion of either, the proposed use of the material is for scholarly purposes. Any copying or use of the material in this document for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Signature: X Date: q/ \ \ 9/ \ THE IMPACT OF THE COLD WAR AND THE SECOND RED SCARE ON THE 1952 AMERICAN PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION BY DANA JOHNS Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Eastern Kentucky University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS 2019 © Copyright by DANA JOHNS 2019 All Rights Reserved.