Positioning Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fællesrådenes Adresser

Fællesrådenes adresser Navn Modtager af post Adresse E-mail Kirkebakken 23 Beder-Malling-Ajstrup Fællesråd Jørgen Friis Bak [email protected] 8330 Beder Langelinie 69 Borum-Lyngby Fællesråd Peter Poulsen Borum 8471 Sabro [email protected] Holger Lyngklip Hoffmannsvej 1 Brabrand-Årslev Fællesråd [email protected] Strøm 8220 Brabrand Møllevangs Allé 167A Christiansbjerg Fællesråd Mette K. Hagensen [email protected] 8200 Aarhus N Jeppe Spure Hans Broges Gade 5, 2. Frederiksbjerg og Langenæs Fællesråd [email protected] Nielsen 8000 Aarhus C Hastruptoften 17 Fællesrådet Hjortshøj Landsbyforum Bjarne S. Bendtsen [email protected] 8530 Hjortshøj Poul Møller Blegdammen 7, st. Fællesrådet for Mølleparken-Vesterbro [email protected] Andersen 8000 Aarhus C [email protected] Fællesrådet for Møllevangen-Fuglebakken- Svenning B. Stendalsvej 13, 1.th. Frydenlund-Charlottenhøj Madsen 8210 Aarhus V Fællesrådet for Aarhus Ø og de bynære Jan Schrøder Helga Pedersens Gade 17, [email protected] havnearealer Christiansen 7. 2, 8000 Aarhus C Gudrunsvej 76, 7. th. Gellerup Fællesråd Helle Hansen [email protected] 8220 Brabrand Jakob Gade Øster Kringelvej 30 B Gl. Egå Fællesråd [email protected] Thomadsen 8250 Egå Navn Modtager af post Adresse E-mail [email protected] Nyvangsvej 9 Harlev Fællesråd Arne Nielsen 8462 Harlev Herredsvej 10 Hasle Fællesråd Klaus Bendixen [email protected] 8210 Aarhus Jens Maibom Lyseng Allé 17 Holme-Højbjerg-Skåde Fællesråd [email protected] -

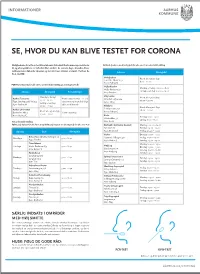

Testmuligheder I Aarhus Kommune

INFORMATIONER SE, HVOR DU KAN BLIVE TESTET FOR CORONA Mulighederne for at få en test bliver løbende forbedret. Der kommer nye teststeder Kviktest (i næsen med kort pind) for alle over 6 år uden tidsbestilling til, og åbningstiderne er forbedret flere steder i de seneste dage. Desuden bliver testkapaciteten løbende tilpasset og sat ind, hvor smitten er størst. Her kan du Adresse Åbningstid få et overblik: Nobelparken Åbent alle ugens dage Jens Chr. Skous Vej 2 8.00 – 20.00 8000 Aarhus C PCR-Test (I halsen) for alle over 2 år med tidsbestilling på coronaprover.dk Vejlby-Risskov Mandag – fredag: 06.00 – 18.00 Vejlby Centervej 51 Lørdag – søndag: 09.00 – 19.00 Adresse Åbningstid Bemærkninger 8240 Risskov Mandag – fredag: Viby Hallen Aarhus Testcenter Handicapparkering er på Åbent alle ugens dage 07.00 – 21.00 Skanderborgvej 224 Tyge Søndergaards Vej 953 testcentret og man skal følge 08.00 – 20.00 Lørdag – søndag: 8260 Viby J 8200 Aarhus N skiltene til kørende 08.00 – 21.00 Filmbyen Åbent alle ugens dage Aarhus Universitet Filmbyen Studie 1 Åbent alle ugens dage 08.00 – 20.00 Bartholins Allé 3 Handicapvenlig 8000 Aarhus C 09.00 – 16.00 8000 Aarhus C Beder Torsdag: 11:00 - 19:00 Kirkebakken 58 Lørdag: 11:00 - 17:00 Test uden tidsbestilling. 8330 Beder PCR test (i halsen for alle fra 2 år og kviktest (i næsen med kort pind) for alle over 6 år. Brabrand - Det Gamle Gasværk Mandag: 09.00 – 19.00 Byleddet 2C Tirsdag: 09.00 – 19.00 Ugedag Sted Åbningstid 8220 Brabrand Fredag: 09.00 – 19.00 Harlev Onsdag: 09:00 - 19:00 Beboerhuset Vest’n, Nyringen 1A Mandage 9.00 - 16.30. -

Landsdækkende Screening Af Geotermi I 28 Fjernvarmeområder

Landsdækkende screening af geotermi i 28 fjernvarmeområder Bilag 3: Områderapport for Aarhus Indholdsfortegnelse – Introduktion – Data for fjernvarmeområder (COWI) – Beregning af geotermianlæg (DFG) – Beregningsresultater vedr. indpasning af geotermi (Ea) – Geologisk vurdering (GEUS) Introduktion Dette er én ud af 28 områderapporter, som viser specifikke økonomiske og produktionsmæssige resultater for hvert enkelt område. Rapporten er et bilag til hovedrapporten ”Landsdækkende screening af geotermi i 28 fjernvarmeområder”, og bør læses i sammenhæng med denne, da hovedrapporten indeholder information, der er væsentlig for at forstå resultatet. Rapporten er udarbejdet for Energistyrelsen af Dansk Fjernvarmes Geotermiselskab, COWI og Ea Energianalyse i perioden efteråret 2013 til sommeren 2015. Områderapporten indeholder den af GEUS udførte geologiske vurdering, COWIs beskrivelse af fjernvarmeområdet og den fremtidige forsyningsstruktur, Dansk Fjernvarmes Geotermiselskabs beregninger af de økonomiske og tekniske forhold i et geotermianlæg i fjernvarmeområdet, og Ea Energianalyses modelresultater fra Balmorel med varmeproduktionskapaciteter, fjernvarmeproduktion og -omkostninger over året for de fire scenarier i årene 2020, 2025 og 2035. Resultaterne skal tages med en række forbehold. Først og fremmest skal det understreges, at der er tale om en screening med det formål at give en indikation af mulighederne for geotermi. Der er ikke foretaget en fuldstændig analyse af den optimale fremtidige fjernvarmeforsyning i området. Den geologiske vurdering er alene foretaget for en enkelt lokalitet, svarende til en umiddelbart vurderet fordelagtig placering af geotermianlægget. Der kan derfor ikke drages konklusioner om hele områdets geologisk potentiale og den optimale placering for et eventuelt geotermianlæg. Modellering af områdets nuværende og forventede fremtidige fjernvarmeproduktion og -struktur er sket ud fra de data, som de var oplyst og forelå i år 2013. -

District Heating and a Danish Heat Atlas

GEOGRAPHICAL REPRESENTATION OF HEAT DEMAND, EFFICIENCY AND SUPPLY LARS GRUNDAHL Project data • Started September 1st 2014 • Finish August 31 2017 • Supervisor: Bernd Möller • Co-supervisors: Henrik Lund and Steffen Nielsen Start-up period (first few months) • Writing 2-month studyplan • Doing courses (17 ECTS by end of December) • Focus on statistics and programming • Actual registered heat consumption data received Objectives • Investigate the difference in the expansion potential of district heating depending on the economic science approach • Identify inaccuracies in the current heat atlas based on a statistical analysis comparing the results with real-world data • Develop methods to identify patterns in the inaccuracies and correlations between the inaccuracies and for example demographic data. Develop methods that improve the accuracy of the heat atlas based on the patterns identified • Contribute to the development of the next generation of heat atlases Study 1 • Comparison of district heating expansion potentials based on private/business consumer economy or socio economy • Aim: Identifying the consequences for the expansion potential of district heating depending on the economical approach used. • Data: Current heat atlas • Methodology: • The expansion potential for each of the current district heating networks to nearby towns and villages is calculated. • The calculations include the costs of transmission, distribution and building installation, as well as, heat production costs. • The heating costs per year are compared with -

1 1. Udg. Dette Indeks Rummer Personer, Steder Og Begivenheder Fra De Femten Optrykte Bind Information 1943-45. Information Fung

1. udg. Dette indeks rummer personer, steder og begivenheder fra de femten optrykte bind Information 1943-45. Information fungerede i årene 1943-45 som den illegale presses nyhedsbureau og rummer et hav af oplysninger. Søg: Søgefunktionen i indekset er enkel: Brug pdf-formatets sædvanlige søgefunktion (CTRL f) og søg på et navn, et sted osv. Brug bindnummer og sidetal til at finde det relevante sted i de trykte bind af Information. Bindene af Information er nummereret med romertal I-XV. Indekset muliggør en samlet søgning i de 15 bind. Alternativt kan man blot pdf-søge direkte i de enkelte bind. Vær opmærksom på, personer i indekset er ordnet efter første efternavn – dvs. John Christmas Møller står under Christmas Møller, John. Ved alle navne og steder er Aa fastholdt. Vær også opmærksom på, at Information ikke kun rummer mange oplysninger, men også mange fejl. Der er ikke redigeret i indeks, og fx er enkelte personer omtalt som stikker, nazist osv., fordi de omtales som sådan i Information. Det betyder ikke, at det er dokumenteret, at disse personer var stikkere. I enkelte tilfælde er der med hård parentes gjort opmærksom på fejl. Enkelte hyppige ord og begreber er udeladt (fx Danmark). Baggrund: De 472 illegale numre af Information (samt særnumre og numre udsendt efter den tyske kapitulation sideløbende med udgivelsen af det legale Information) blev udgivet i 15 bind i 1976-78 under redaktion af Jørgen Barfod, Frihedsmuseet, forlægger Jens Nordlunde, Informations redaktør Børge Outze, rektor Palle Schmidt, Esbjerg og antikvarboghandler Lars Zachariassen. Redaktionens bestræbelser på at forsyne bindene med et fælles indeks strandede. -

Straw for Energy Production. Technology

Straw for Energy Production Technology - Environment - Economy The Centre for Biomass Technology 1998 Straw for Energy Production has been prepared in 1998 by The Centre for Biomass Technology (www.sh.dk/~cbt ) on behalf of the Danish Energy Agency. The publication can be found on the web site: www.ens.dk . The paper edition can be ordered through the Danish Energy Agency or The Centre for Biomass Technology at the following addresses: • Danish Energy Agency 44 Amaliegade DK-1256 Copenhagen K Tel+45 33 92 67 00 Fax +45 33 11 47 43 www.ens.dk • Danish Technological Institute Teknologiparken DK-8000 Aarhus C Tel +45 89 43 89 43 Fax +45 89 43 85 43 www.dti.dk • dk-TEKNIK 15 Gladsaxe Mellevej DK-2860 Soborg Tel +45 39 55 59 99 Fax +45 39 69 60 02 www.dk-teknik.dk • Research Centre Bygholm 17 Schiittesvej DK-8700 Horsens Tel +45 75 60 22 11 Fax +45 75 62 48 80 www.agrsci.dk Authors: Lars Nikolaisen (Editor) Carsten Nielsen Mogens G. Larsen Villy Nielsen Uwe Zielke Jens Kristian Kristensen Birgitte Holm-Christensen Cover photo: Lars Nikolaisen, Danish Technological Institute and M. Carrebye, SK Energi Layout: BioPress Printed by: Trojborg Bogtryk. Printed on 100% recycled paper ISBN: 87-90074-20-3 DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document. Straw for Energy Production Technology - Environment - Economy Second Edition The Centre for Biomass Technology 1998 Contents Foreword...........................................................................................................................................................................5 1 Danish Energy Policy................................................................................................................................................. 6 2 Straw as Energy Resource...................................................................................................................................... -

Anticipating Organizational Change: a Study of the Pre-Implementation Phase of Sundhedsplatformen

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Krogh, Simon Doctoral Thesis Anticipating Organizational Change: A Study of the Pre-implementation Phase of Sundhedsplatformen PhD Series, No. 51.2016 Provided in Cooperation with: Copenhagen Business School (CBS) Suggested Citation: Krogh, Simon (2016) : Anticipating Organizational Change: A Study of the Pre-implementation Phase of Sundhedsplatformen, PhD Series, No. 51.2016, ISBN 9788793483675, Copenhagen Business School (CBS), Frederiksberg, http://hdl.handle.net/10398/9396 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/209005 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen -

Solbjerg Fællesråd Dagsorden

Dagsorden: FU møde 26.11.2018 Emne: Forretningsudvalgsmøde Dato: 26.11.2018, kl. 19.15- 21.30 Sted: Fritidscentret, Solbjerg Hovedgade Forretningsudvalg: Brian Jonassen Jens Sejr Jensen Solbjerg Fællesråd Susanne Hillers Karsten Stær Forretningsudvalg Lene Staub Mads K. Thomsen c/o Brian Jonassen Afbud: Susanne Juul Jakobsen Kærgårdsparken 133 8355 Solbjerg Referent: Cvr-nr. 18837846 Reg. nr. 5381 Dagsorden forretningsudvalgsmøde Konto nr. 0000246823 1. Godkendelse af mødereferat af 29.10.2018 E-post: 2. Opsamling på to-do liste (KS) [email protected] 3. Orientering § 8 underudvalg Hjemmeside: www.Solbjergnu.dk 01 Økonomiudvalg - BJ og Henning mødes for adgang til e-boks - Tilgodehavende Fruerlund - Aarhus Brandvæsen, Faktura service hjertestarter - Ansøgning tilskud fællesråd 2019 Bilag 1.0 02 Arrangementsudvalg - Status, Julearrangement 1. december (LSJ) - To-do liste, Julefrokost Solbjerg Fællesråd 3. december (LSJ) 03 SolbjergNU medlemsblad - Procedure for SolbjergNU i farver (SUS/BJ) - Tilbud og kontraktoplæg (Lukket pkt.) 04 SolbjergNU hjemmeside - Ønske om Goggle bykalender på hjemmeside (forsøg) (BJ) 05 Solbjerg Aftenskole - F2019 programmet offentliggjort (5 yogahold) Solbjerg Fællesråd Forretningsudvalg 06 Solbjerg Beboerhus - Opfølgning på SIF arrangement lørdag d. 17.11.2018 (lukket pkt.) 07 Solbjerg Flagallé - 08 Tryghedsnetværk - 09 Veje og stiudvalg - Trafikale forhold Solbjerg og Aarhus Kommune (MKT) Tirsdag d. 20.11.2018 (Lars Clausen, MKT, Louise Perry) 4. Ad hoc opgaver Orienterende - Frivilligfest 5. december 2018 Bilag 2.0 - Formandsmøde d. 29. november for Fællesråd BJ har meldt afbud Beslutning - VE Anlæg Nyhedsbrev 10 Bilag 3.0 VE anlæg ved Solbjerg - Aarhus Kommune, Lokalplan Solbjerg Byport Borgermøde Solbjergskolens festsal 20.11.2018 - Ny bebyggelse Østergårdsvej, Solbjerg (BJ) Høringssvar deadline 30.11.2018 – input? Årshjuls opgaver - 5. -

Heat Generation in Denmark

APRIL 2016 HEAT GENERATION IN DENMARK The Danish district heating system supplies technologies distributed between multiple need not worry whether there is heat in almost three-quarters of the population plants. their radiators and hot water in their taps. with heating. There are around 400 district The technologies currently available The reason for this is that all plants operate heating companies in Denmark, which also include CO2-free sources of heat such reserve load boilers, typically gas- or oil- either generate the heat themselves or buy as solar and geothermal heat. In addition, fired. These boilers are brought online if the it from other production companies. The many places also exploit surplus heat from CHP plant fails to deliver, but they are also heat is generated in many different ways, industrial facilities to supply district heating, useful during the winter months when more using a wide variety of fuels. Most of the and other plants likewise use heat pumps heat production is required. production takes place in CHP plants that and electricity cartridges to utilise the elec- generate both electricity and heat. They do tricity generated by wind turbines. OWNERSHIP so by harvesting energy from a number of In practice, the district heating system 340 district heating companies in Denmark different fuels such as waiste, gas, coal and actually functions like a giant battery with are cooperative societies owned by the biomass. the capacity to assimilate and store produc- users, 50 are municipally owned and only Some district heating companies use tion from other energy technologies. few are in private hand. -

Anlægskatalog Mobilitet Frem Mod 2050

ANLÆGSKATALOG MOBILITET FREM MOD 2050 VEJNETTET INTELLIGENTE TRANSPORTSYSTEMER KOLLEKTIV TRAFIK CYKLING OG GANG INDLEDNING Anlægskataloget beskriver 71 projekter, der – enkeltvist og Nogle af projekterne i Anlægskataloget er allerede besluttet, og samlet - kan medvirke til at sikre en forbedring af mobiliteten i finansieringen er aftalt. Disse projekter er inkluderet i Anlægska- Aarhus Kommune. Projekterne er præsenteret (gruppevist) i fire taloget for at give et samlet billede af projekter, der kan forbedre indsatsområder: Vejnettet, Intelligente TransportSystemer, mobiliteten frem mod 2050. De besluttede projekter er i anlægs- Kollektiv trafik samt Cykling og gang. overslaget markeret med teksten ” BESLUTTET”. I ”Mobilitet frem mod 2050 – Investeringsbehov og hand- For hvert projektforslag i Anlægskataloget er der anført et lingskatalog” (september 2019) findes en beskrivende tekst anlægsoverslag over udgifterne. Da nogle projekter er meget til de fire indsatsområder. I handlingskataloget anbefales det, bearbejdede i forhold til andre, er der en stor forskel på, hvor hvornår projekterne med fordel kan udføres. I handlingskataloget præcist anlægsoverslagets beløb kan angives. Ved projekter, der er projekterne opdelt efter, om de anbefales udført på kort sigt ikke er detaljerede, vil der derfor ofte stå ”Groft anlægsoverslag”, (0-10 år), mellem sigt (10-20 år) eller med et langt sigte frem hvilket angiver, at projektafklaringer kan medføre markante mod 2050. justeringer af prisen. Projekterne i Anlægskataloget er præsenteret i en ikke prioriteret Effekten af de enkelte projekter er ikke vurderet ved alle projek- rækkefølge. ter. Effekten skal vurderes forud for endelig vedtagelse. ORDFORKLARING: I Anlægskataloget er hvert projekt beskrevet med en kortfattet tekst med et tilhørende oversigtskort samt et anlægsover- slag. I teksterne indgår fagtermer. -

Vindmøller Mårup

VINDMØLLER MÅRUP GRUNDLAG OG FORUDSÆTNINGER Byrådet har som mål, at Århus Kommune skal væ- re CO 2-neutral i 2030. Derfor ønsker Byrådet at give gode muligheder for produktion af vedvaren- de energi. MEJLBY På den baggrund er der i forBindelse med udar- Bejdelse af Kommuneplan 2009 blevet gennem- ført en undersøgelse af placeringsmuligheder for HÅRUP større vindmøller i Århus Kommune. Undersøgel- sen er mundet ud i, at der i Kommuneplan 2009 udpeges 6 områder, der findes umiddelBart egne- de til placering af større vindmøller. Derudover er det vurderet, at vindmøller på havnen kan være en mulighed set i sammenhæng med en kommende for vindmøller i størrelsesordnen 125-150 m total- havneudvidelse. De udpegede områder fremgår af højde – det vil sige højden målt til vingespids, når kortene de følgende sider. spidsen er højest over terræn. Udpegningen af vindmølleområder skal ske under Udpegningen af mulige vindmølleområder er i hensyntagen til naBoer, landskab og natur. Det er overensstemmelse med Regeringens langsigte- i denne afvejning af interesser blevet vurderet, at de energiudspil og vision om, at 30 % af energi- opstilling af vindmøller som udgangspunkt kun forBruget fremover skal stamme fra vedvarende skal være en mulighed, når det kan forventes, at energi. Som et skridt på vejen hertil har regerin- produktionen af vedvarende energi er tilstrækkelig gen i maj 2008 indgået energiaftale med Kommu- stor. De områder, der er udpegede som umiddel- nernes Landsforening om arealreservation til op- Bart egnede vindmølleområder, forBeholdes der- stilling af nye landvindmøller med en samlet ka- pacitet på 150 MW på landsplan ved udgangen af 2011. Vindmøllernes CO2-besparelser Der findes i dag 5 vindmølleområder i Århus Kom- Vindmøllerne vil bidrage aktivt til at nedsætte Århus Kom- mune, der alle er fuldt udByggede. -

Har Du Krammet På Din Computer?

Selvbetjening på nettet Du sparer tid – kommunen sparer penge Har du krammet på din Selvbetjening på nettet har en række fordele. For os som borgere betyder det, computer? at vi kan ordne vores sager med kommunen, når det passer os – uafhængigt af åbningstiderne, PC-KURSER I og for kommunerne betyder det, at der er rigtig mange SELVBETJENING penge at spare. Selvbetjening på nettet er betydeligt billigere for kommunerne end breve og telefonopkald. Og det er det DATASTUER sidste, der gør, at regeringen har besluttet, at al i Aarhus Kommune kommunikation mellem borgere og offentlige myndigheder skal være digital – dvs. ske via nettet – fra 2014. Så der er På de fleste ingen vej uden om - hverken for kommunerne eller borgerne. datastuer kan du Derfor rækker Borgerservice i Aarhus Kommune nu få hjælp til seniorerne en hjælpende hånd i et nært samarbejde med offentlig frivillighuse, lokalcentre, datastuer, biblioteker og Ældre selvbetjening Sagen. Lige nu er en række frivillige it-undervisere ved at blive uddannet i kommunens selvbetjenings-løsninger, sådan at det er en del af programmet fra årsskiftet. Der er lavet en særlig side på Aarhus Kommunes hjemmeside, der fortæller, hvilke muligheder du har for at deltage i kurser i digital kommunikation med kommunen. Adressen er: www.aarhus.dk/seniorit BORGERSERVICE december 2011 DATASTUER i Aarhus Kommune KLUB KONTAKTPERSON & TLF ADRESSE EMAIL EVT. HJEMMESIDE Bjerggårdens Internetcafé Datastuen Rosenbakken EDB Gruppen Skåde Senior Netcafé Kjeld Kibsgaard 86 16 05 46 Knud E. Dahlerup 86 99 31 60 Heinz Thomsen 21 91 58 48 Finn Olesen 86 21 23 59 / 20 32 53 59 Lokalcenter Bjerggården Lokalcenter Rosenbakken Lokalcenter Skåde, Frivillighuset Østerøgade 18, 8200 Aarhus N Grenåvej 701, 8541 Skødstrup Bushøjvænget 113, 8270 Højbjerg Skt.