Conceptualisation of Joint Ventures in EU Competition Law As Compared to the Approach in the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Project Report on ³INVENTORY MANAGEMENT´

A Project Report on ³INVENTORY MANAGEMENT´ SUBMITTED BY: Mujif Rahuman M. 520828621 Operations Management Submitted in fulfillment of the requirement of IVth Semester of MBA course, Sikkim Manipal University 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION INVENTORY MANAGEMENT««««««««2 SIEMENS«««««««««««««««««««««.........8 OBJECTIVES AND NEED OF SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT..16 ACTIVITIES/FUNCTIONS OF SCM IN SIEMENS«««««.20 INVENTORY CONTROL MANAGEMENT««««««««25 WAREHOUSE««««««««««««««««««««..43 TRANSPORTATION««««««««««««««««.«.45 DISTRIBUTION«««««««««««««««««««..48 PACKAGING AND LABELLING««««««««««««.53 CONCLUSION««««««««««««««««««««.59 2 INVENTORY MANAGEMENT 1. INTRODUCTION DEFINATION AND MEANING Inventory is a list of goods and materials, or those goods and materials themselves, held available in stock by a business. Inventory are held in order to manage and hide from the customer the fact that manufacture/supply delay is longer than delivery delay, and also to ease the effect of imperfections in the manufacturing process that lower production efficiencies if production capacity stands idle for lack of materials. The reasons for keeping stock All these stock reasons can apply to any owner or product stage. Buffer stock is held in individual workstations against the possibility that the upstream workstation may be a little delayed in providing the next item for processing. Whilst some processes carry very large buffer stocks, Toyota moved to one (or a few items) and has now moved to eliminate this stock type. Safety stock is held against process or machine failure in the hope/belief that the failure can be repaired before the stock runs out. This type of stock can be eliminated by programmes like Total Productive Maintenance Overproduction is held because the forecast and the actual sales did not match. -

Glauce Almeida Figueira

GLAUCE ALMEIDA FIGUEIRA A Sustentabilidade na Estratégia Empresarial: Estudo de Caso do Grupo Siemens AG Campinas 2014 i iii iv v DEDICATÓRIA Dedico este trabalho ao meu marido Guilherme e meus dois filhos Rafael e Luiza pelo amor e compreensão durante todo o tempo de realização deste trabalho. vii Agradecimentos Ao Professor Bastiaan Philip Reydon pelo incentivo e direcionamento em pesquisar um tema tão importante nos dias de hoje, além da paciência e tranquilidade na orientação desse trabalho. À Professora Rachel Stefanuto Cavalcanti por me abrir os olhos para as verdadeiras questões socioambientais e as portas do conhecimento sobre o tema do desenvolvimento sustentável, além das importantes contribuições no exame de qualificação. À Professora Maria Carolina Azevedo Ferreira de Souza por ter fornecido valiosos comentários no exame de qualificação, que levaram a diversas reformulações em todos os capítulos do trabalho. Ao meu marido, Guilherme Faber Boog, por possibilitar a realização do estudo de caso junto ao Grupo Siemens AG, auxiliando nos contatos e obtenção de informações necessárias para a realização deste trabalho. A minha sogra, Professora Maria Cristina Faber Boog, pelo apoio em todos os momentos e pela disposição em ler e comentar diversas versões do trabalho, mesmo não sendo sua área de especialidade. Ao meu sogro, Professor Emilio Grueneberg Boog, pelo incentivo e apoio ao objetivo de me tornar mestra e poder ministrar aulas com conhecimento e convicção. A minha amiga e comadre Ana Letícia Tarckiani dos Santos que, dentre outras inúmeras qualidades, é uma ótima ouvinte. Aos professores da UNICAMP que me forneceram importantes informações, tanto para a elaboração do trabalho, como para aprimorar minhas aulas, ministrando-as de maneira mais crítica e diversificada. -

Aufstellung Des Anteilsbesitzes Des Siemens Konzerns Gemäß § 313 Abs

Aufstellung des Anteilsbesitzes des Siemens Konzerns gemäß § 313 Abs. 2 HGB Kapital- anteil Stand 30.9.2002 in % I. Verbundene Unternehmen A. Konsolidiert 1. Deutschland (208 Gesellschaften) ACHH Grundstücksentwicklungs-GmbH & Co. OHG, Erlangen 1004) ACHH Grundstücksentwicklungs-Verwaltungsgesellschaft mbH, Erlangen 100 Alarmcom GmbH, Filderstadt-Bonlanden 100 Allgemeine Assekuranz-Vermittlung Duisburg GmbH, Duisburg 100 Atecs Mannesmann AG, Düsseldorf 1001) Audio Service GmbH, Herford 100 BFE Studio und Medien Systeme GmbH, Mainz 100 bibis Information Technology and Services GmbH, Dortmund 100 CAPTA Grundstücks-Verwaltungsgesellschaft mbH & Co. OHG, Grünwald 1004) Divipart Aktiengesellschaft & Co. Grundstücks KG, Frankfurt am Main 100 Duewag AG, Krefeld-Uerdingen 99 Elektro-Röhren-Gesellschaft beschränkt haftende OHG, Göttingen 100 Elektro-Röhren-Gesellschaft mbH, Göttingen 100 Fertigungscenter für Elektrische Anlagen Bremen GmbH, Bremen 100 Fertigungscenter für Elektrische Anlagen Erlangen GmbH, Erlangen 100 Fertigungscenter für Elektrische Anlagen Hannover GmbH, Hannover 100 Fertigungscenter für Elektrische Anlagen Köln GmbH, Köln 100 Fertigungscenter für Elektrische Anlagen Langen GmbH, Mörfelden-Walldorf 100 Fertigungscenter für Elektrische Anlagen St. Ingbert GmbH, St. Ingbert 100 Frankendata Softwareengineering GmbH & Co. KG, Erlangen 100 Frankendata Softwareengineering Verwaltungsgesellschaft mbH, Erlangen 100 Gerap Grundbesitz- und Verwaltungsgesellschaft mbH, Frankfurt am Main 100 GIT Gesellschaft für Ingenieur-Technik mbH, -

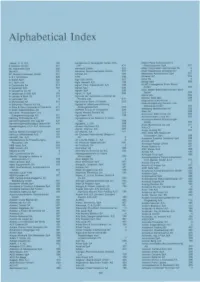

Alphabetical Index

Alphabetical Index H0yer. 0 G, "IS 10< Aaroportos a Navega!fiio Aarea ANA- AUlanz Pace Ass;cura>:ioni e 3 Glacken GmbH 221 EP AiassTcurazioni SpA 337 3C Industriale SpA 335 Aeroquip GmbH '" Allied Corporation International NV • 3M AIS 107 ABrzenef Maschinenlabrik GmbH '"'22 Allied Stevedores (Antwerp) NV • 4P Nicolaus Kempten GmbH "flimel SA 185 Allsecures Assicurazioni SpA 337 A & L Simonazll 335'" AFM 186 Allweilsf AG A Agral; SpA 335 Aga Gas GmbH "1m3 NV '"• A Cilium AIS 107 Agla Gevaer! AIS '"108 Almag SpA 338 A CounlnlOlis SA 313 Agnar, Paul. Fiskeindustrl AIS 108 ALMO Erzeugl1isse Erwio Busch fA. Espersen AIS 107 Agnatl SpA 336 GmbH Alols Zettler Elektrotechnische Fabrik A Gevaerl & Co NV 3 Agnesl SpA 336 '" GmbH A Jespersen & Sen A!S 107 Agrati, A, SpA 336 Alpine AG A lekkas & Bros SA 313 Agricola de Lacticinlos a Cerllral de '" Alpltour Italia SpA 336 A Lommaert NV 3 Peralita Lda '" Alsaclenne d'Alumlnium 185 A Michailides SA 313 Agricultural Bank of Greece '"313 Aisen-Breitenburg Zement- coO A Schulmen Plastics NV-SA 3 Agrippina Lebensversicherung Kalkwarlea GmbH A Silva & Silva Industrlas e Comarcio Aktiengesellschaft Allenberg Metallwerke AG 225 A Stolz Maschinenbau AG '" AGROB Group 01 Companies '" '" Alter SA 508 Aachener Sirassenbahn und Agrob Wessel ServaIs AG '" '" Aluminium Werle Unna AG 225 Enargieversorgungs AG Agro-kemi AIS 108 '" Aluminiumwerk Unna AG Aalborg Stil1slidende AIS 107 Agropecuaria de Navarra, SCoop, '" Aluminium-Werke Wijtoschingen Aannemingsbedrijf Van Lee BV Ltda 508 '" GmbH Aennemingsmaatschappij GElbam -

Air Traffic Management Abbreviation Compendium

Air Traffic Management Abbreviation Compendium List of Aviation, Aerospace and Aeronautical Acronyms DLR-IB-FL-BS-2021-1 Institute of Air Traffic Management Abbreviation Compendium Flight Guidance Document properties Title Air Traffic Management Abbreviation Compendium Subject List of Aviation, Aerospace and Aeronautical Acronyms Institute Institute of Flight Guidance, Braunschweig, German Aerospace Center, Germany Authors Nikolai Rieck, Marco-Michael Temme IB-Number DLR-IB-FL-BS-2021-1 Date 2021-01-28 Version 1.0 Title: Air Traffic Management Abbreviation Compendium Date: 2021-01-28 Page: 2 Version: 1.0 Authors: N. Rieck & M.-M. Temme Institute of Air Traffic Management Abbreviation Compendium Flight Guidance Index of contents 2.1. Numbers and Punctuation Marks _______________________________________________________ 6 2.2. Letter - A ___________________________________________________________________________ 7 2.3. Letter - B ___________________________________________________________________________ 55 2.4. Letter - C __________________________________________________________________________ 64 2.5. Letter - D _________________________________________________________________________ 102 2.6. Letter - E __________________________________________________________________________ 128 2.7. Letter - F __________________________________________________________________________ 152 2.8. Letter - G _________________________________________________________________________ 170 2.9. Letter - H _________________________________________________________________________ -

Ministry of Defence Acronyms and Abbreviations

Acronym Long Title 1ACC No. 1 Air Control Centre 1SL First Sea Lord 200D Second OOD 200W Second 00W 2C Second Customer 2C (CL) Second Customer (Core Leadership) 2C (PM) Second Customer (Pivotal Management) 2CMG Customer 2 Management Group 2IC Second in Command 2Lt Second Lieutenant 2nd PUS Second Permanent Under Secretary of State 2SL Second Sea Lord 2SL/CNH Second Sea Lord Commander in Chief Naval Home Command 3GL Third Generation Language 3IC Third in Command 3PL Third Party Logistics 3PN Third Party Nationals 4C Co‐operation Co‐ordination Communication Control 4GL Fourth Generation Language A&A Alteration & Addition A&A Approval and Authorisation A&AEW Avionics And Air Electronic Warfare A&E Assurance and Evaluations A&ER Ammunition and Explosives Regulations A&F Assessment and Feedback A&RP Activity & Resource Planning A&SD Arms and Service Director A/AS Advanced/Advanced Supplementary A/D conv Analogue/ Digital Conversion A/G Air‐to‐Ground A/G/A Air Ground Air A/R As Required A/S Anti‐Submarine A/S or AS Anti Submarine A/WST Avionic/Weapons, Systems Trainer A3*G Acquisition 3‐Star Group A3I Accelerated Architecture Acquisition Initiative A3P Advanced Avionics Architectures and Packaging AA Acceptance Authority AA Active Adjunct AA Administering Authority AA Administrative Assistant AA Air Adviser AA Air Attache AA Air‐to‐Air AA Alternative Assumption AA Anti‐Aircraft AA Application Administrator AA Area Administrator AA Australian Army AAA Anti‐Aircraft Artillery AAA Automatic Anti‐Aircraft AAAD Airborne Anti‐Armour Defence Acronym -

European Semiconductor Industry Service (ESIS) Have Received This Data As a Loose-Leaf Service Section to Be Filed in Their Binder Set

DataQuest a company of MThe Dun & Bradstreet Corporation 7th April Dear Client, NEW FORMAT—MARKET SHARE DATA Dataquest's Eviropean Components Group completed preliminary 1988 European semiconductor market share estimates, which are enclosed herein. In the past, clients of the European Semiconductor Industry Service (ESIS) have received this data as a loose-leaf service section to be filed in their binder set. For your convenience we are now publishing this data in the form of a booklet. This booklet can still be filed as before, but offers much greater ease of use "on the move". We have also presented the market share estimates in a ranked format, rather than in alphabetical format, for your ease in comparing of vendors' market positions in different products and technologies. The previous year's rank is also shown for reference. Extra analysis is given, such as percentage market share for each vendor, for further ease in interpreting the estimates. We hope this helps make our estimates more usefuL to you. We would be interested in your comments regarding this new format. Yours sincerely %Y^^ • Bypon Harding Research Analyst European Components Group. 1290 Ridder Park Drive, San Jose, CA 95131-2398 (408) 437-8000 Telex 171973 Fax (408) 437-0292 European Semiconductor Industry Service Volume III—Companies E)ataQuest nn acompanyof IISI TheDun&Biadstreetcorporation 12^ Ridder Park Drive San Jose, California 95131-2398 (408) 437-8000 Telex: 171973 I^: (408) 437-0292 Sales/Service Offices: UNITED KINGDOM FRANCE EASTERN U.S. Dataquest Europe Limited Dataquest Europe SA Dataquest Boston Roussel House, Tour Gallieni 2 1740 Massachusetts Ave. -

Aerospace, Defence, and Government Services Mergers & Acquisitions

Aerospace, Defence, and Government Services Mergers & Acquisitions - European (January 1993 - April 2020) BAE L3Harris Rolls- Airbus Hensoldt Boeing Cobham Dassault Elbit General Dynamics GE GKN Honeywell Indra Kongsberg Leonardo Lockheed Martin Meggitt Northrop Grumman Rheinmetall Saab Safran Thales Ultra Raytheon Technologies Systems Aviation Systems Sistemas Technologies Royce Electronics Airborne tactical PFW Aerospace to Aviolinx Raytheon Kopter Group Atmos Sistemas Advent Hydroid to Huntington Airport security radio business to Hutchinson Bombardier C Series airborne tactical Leonardo&Codemar businesses to Leidos Vector Launch Otis & Carrier businesses BAE Systems ALP stake [25%] radios business Int’l Ingalls Industries JV [51%] Controls & Data TCS EW business to to Shareholders IE Asia-Pacific Sistemas Services to Valsef Telemus United Raytheon MTM Robotics buyout Jet Aviation Vienna Distributed Energy GERAC test lab and PK AirFinance to Informaticos Abiertas Night Vision business Rheinmetall MAN Base2 Solutions engineering to Sopemea Technologies 2 Inventory Locator Service to L3Harris Hamble aerostructure Solutions business to TRC Military Vehicles eAircraft 2 GDI Simulation to MBDA Alestis Aerospace stake [76%] NEXEYA CAMP Systems International Night Vision Apollo and Athene to Elbit Systems Stormscope product BAE Systems UK to Belcan Collins Psibernetix ElectroMechanical Websense to Aciturri Aeronautica RBSL JV w/ business to Aernnova Medav Technologies NVH stake [19.5%] 0 RUAG Switzerland Next Generation 911 to line to TransDigm -

The Challenge of Globalization for Large Chinese Firms

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT THE CHALLENGE OF GLOBALIZATION FOR LARGE CHINESE FIRMS Peter Nolan and Jin Zhang No. 162 July 2002 DISCUSSION PAPERS THE CHALLENGE OF GLOBALIZATION FOR LARGE CHINESE FIRMS Peter Nolan and Jin Zhang No. 162 July 2002 UNCTAD/OSG/DP/162 ii The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNCTAD. The designations and terminology employed are also those of the author. UNCTAD Discussion Papers are read anonymously by at least one referee, whose comments are taken into account before publication. Comments on this paper are invited and may be addressed to the author, c/o the Publications Assistant,* Macroeconomic and Development Policies, GDS, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. Copies of Discussion Papers may also be obtained from this address. New Discussion Papers are available on the website at: http.//www.unctad.org/en/pub/pubframe/htm * Fax: (+41) (0)22.907.0274; E-mail: [email protected] JEL classification: F2, L1, M2, O2, P2 iii CONTENTS Page Abstract................................................................................................................................ 1 I. CHINA AND THE GLOBAL BUSINESS REVOLUTION ........................................................... 1 A. China’s reforms ................................................................................................. 2 1. Lessons from other countries .................................................................... -

Identification Systems/Surveillance and Databases Still Recorded on the Databases of (SAIC- )NSI Cell-Phone Tapping

Schengen Information System The countries participating in the system formati are: Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, In on en S Spain, Austria, Greece, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Iceland and Norway. The Atos installs the Schengen Central Information System, renovated in g sw de y Intergraph (UK) Ltd n s data sets entered by the Schengen states amounted to almost 12 million in e da t Partnership with IBM and CSC. système d’information européen (SIE) e STIC (Système de Traitement des Infractions Constatées) système d’information douanier (SID) h late 1999. The major data suppliers are Germany, France and Italy. The Delta Business Park po ho m As prime contractor, Atos is in charge of designing and managing the project c Computer strasbourg Great Western Way Intergraph I.B.M. Atos France civil status S Netherlands, Belgium, and Greece also carry out a rather extensive transfer Vodafone in partnership with IBM and CSC. The principal challenges of the project, Sciences be gr of their data. Spain and Portugal appear somewhat less zealous. Beyond its Swindon SN5 7XP which involves more than 30 person-years, are to ensure reliability, security domicile UK Corporation Telecom infraction committed fr sheer capacity, the efficiency of the SIS is measured by speed. The entry or fidelity manag. and inter-operability. The strong fit between the three partners' areas of it es updating of a notice in a country is transmitted to the central system. This Tel: 0793 619999 expertise, their extensive experience in implementing national Schengen (CSC) objects http://www.intergraph.com (4.5 million objects) system validates the data after a technical check and retransmits it to all the & res. -

R-V-BAE Sentencing Remarks

Case No: S2010565 IN THE CROWN COURT AT SOUTHWARK 1 English Grounds (off Battlebridge Lane) Southwark London England SE1 2HU Date: 21/12/2010 Before: MR. JUSTICE BEAN - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between: R - and - BAE SYSTEMS PLC Victor Temple QC, Timothy Cray and Louis Mably for the prosecution David Perry QC and Miranda Hill for the defendant R V BAE SYSTEMS PLC Mr. Justice Bean: 1. On 23rd November 2010 at the City of Westminster Magistrates Court. BAE Systems PLC (“the Company”) pleaded guilty to one offence of failing to keep accounting records “sufficient to show and explain the transactions of the company” contrary to Section 221 of the Companies Act 1985. District Judge Tubbs committed the case to the Crown Court for sentence. 2. The laying of the information on 5th November 2010 came after a Settlement Agreement between the Company and the Serious Fraud Office. This provided, so far as material, as follows: 2) The Company shall plead guilty to a charge in the form attached of one count under section 221 Companies Act 1985. 3) The basis of plea in relation to that charge shall be in the form attached. The Company shall admit the facts set out therein and enter a plea in mitigation. The SFO will provide a copy of its opening note by 19 February 2010. 4) The fine for the offence admitted shall be imposed by the Court. 5) The Company shall make an ex gratia payment for the benefit of the people of Tanzania in a manner to be agreed between the SFO and the Company. -

Aviation Abbreviations

AVIATION ABBREVIATIONS Mahan Air Documentation Center Edition 1 2014/04/23 Alpha (ICAO) A A/A Air-to-air (ICAO) A/C Aircraft AA Approved Urgency (CFMU) AA Aircraft Address (IFPS SSR MODE-S) AAAS Amadeus Airline Ancillary Services AABC ARINC Automated Border Control AAC Airworthiness Advisory Circular (CASA) AAC Airline Administrative Communication (ACP) AACC Airport Associations Coordinating Council (ACI / AACI) AACE Airfield Approach Control Element AACI Airports Association Council International (ACI) AACO Arab Air Carriers Organisation AAD Assigned Altitude Deviation (ICAO) AAE Above Aerodrome Elevation (CA) AAF ATM Added Functions AAFCE Allied Air Forces Central Europe AAG AIS Automation Group AAGDI Automated Air / Ground Data Interchange AAH Autonomous Aircraft Hybrid AAI Arrival Aircraft Interval (FAA AAR) AAI Angle of Approach Indicator AAIB Air Accident Investigation Branch (UK equivalent of NTSB) AAIM Aircraft Autonomous Integrity Monitoring (ICAO) AAIS Automated AIS AAL Altitude Above Aerodrome level (ICAO) AALS Advanced Approach and Landing System AAM Airbus Asset Management AAM Airline Administration Message AAME Association of Aviation Medical Examiners AAP Advanced Automation Program AAP Accident Analysis & Prevention (IFALPA) AAPA Association of Asia Pacific Airlines AAR Airport Acceptance Rate or Airport Arrival Rate (FAA) AAR Air to Air Refueling or Automated Aerial Refueling (Boeing) AAS Advanced Automated System (FAA) AASA Air Lines Association of Southern Africa AASC Airport Authorities Steering Committee AASI Aeronautical