Ethnographies of Islam : Ritual Performances and Everyday Practices Baudouin Dupret Editor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rituals and Sacraments

Rituals and Sacraments Rituals, Sacraments (Christian View) By Dr. Thomas Fisch Christians, like their Islamic brothers and sisters, pray to God regularly. Much like Islam, the most important Christian prayer is praise and thanksgiving given to God. Christians pray morning and evening, either alone or with others, and at meals. But among the most important Christian prayers are the community ritual celebrations known as "The Sacraments" [from Latin, meaning "signs"]. Christians also celebrate seasons and festival days [see Feasts and Seasons]. Christians believe that Jesus of Nazareth, who taught throughout Galilee and Judea and who died on a cross, was raised from the dead by God in order to reveal the full extent of God's love for all human beings. Jesus reveals God's saving love through the Christian Scriptures (the New Testament) and through the community of those who believe in him, "the Church," whose lives and whose love for their fellow human beings are meant to be witnesses and signs of the fullness of God's love. Within the community of the Christian Church these important ritual celebrations of worship, the sacraments, take place. Their purpose is to build up the Christian community, and each individual Christian within it, in a way that will make the Church as a whole and all Christians more and more powerful and effective witnesses and heralds of God's love for all people and of God's desire to give everlasting life to all human beings. Each of the sacraments is fundamentally an action of worship and prayer. Ideally, each is celebrated in a community ritual prayer-action in which everyone present participates in worshipping God. -

Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism

Journal of Education & Social Policy Vol. 1 No. 1; June 2014 Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism Shahida Bilqies Research Scholar, Shah-i-Hamadan Institute of Islamic Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006 Jammu and Kashmir, India. Sufism, being the marrow of the bone or the inner dimension of the Islamic revelation, is the means par excellence whereby Tawhid is achieved. All Muslims believe in Unity as expressed in the most Universal sense possible by the Shahadah, la ilaha ill’Allah. The Sufi has realized the mysteries of Tawhid, who knows what this assertion means. It is only he who sees God everywhere.1 Sufism can also be explained from the perspective of the three basic religious attitudes mentioned in the Qur’an. These are the attitudes of Islam, Iman and Ihsan.There is a Hadith of the Prophet (saw) which describes the three attitudes separately as components of Din (religion), while several other traditions in the Kitab-ul-Iman of Sahih Bukhari discuss Islam and Iman as distinct attitudes varying in religious significance. These are also mentioned as having various degrees of intensity and varieties in themselves. The attitude of Islam, which has given its name to the Islamic religion, means Submission to the Will of Allah. This is the minimum qualification for being a Muslim. Technically, it implies an acceptance, even if only formal, of the teachings contained in the Qur’an and the Traditions of the Prophet (saw). Iman is a more advanced stage in the field of religion than Islam. It designates a further penetration into the heart of religion and a firm faith in its teachings. -

Historical Dictionary of Sufism

04-655 (1) FM.qxd 4/18/05 12:39 PM Page i HISTORICAL DICTIONARIES OF RELIGIONS, PHILOSOPHIES, AND MOVEMENTS Jon Woronoff, Series Editor 1. Buddhism, by Charles S. Prebish, 1993 2. Mormonism, by Davis Bitton, 1994. Out of print. See No. 32. 3. Ecumenical Christianity, by Ans Joachim van der Bent, 1994 4. Terrorism, by Sean Anderson and Stephen Sloan, 1995. Out of print. See No. 41. 5. Sikhism, by W. H. McLeod, 1995 6. Feminism, by Janet K. Boles and Diane Long Hoeveler, 1995. Out of print. See No. 52. 7. Olympic Movement, by Ian Buchanan and Bill Mallon, 1995. Out of print. See No. 39. 8. Methodism, by Charles Yrigoyen Jr. and Susan E. Warrick, 1996. Out of Print. See No. 57. 9. Orthodox Church, by Michael Prokurat, Alexander Golitzin, and Michael D. Peterson, 1996 10. Organized Labor, by James C. Docherty, 1996. Out of print. See No. 50. 11. Civil Rights Movement, by Ralph E. Luker, 1997 12. Catholicism, by William J. Collinge, 1997 13. Hinduism, by Bruce M. Sullivan, 1997 14. North American Environmentalism, by Edward R. Wells and Alan M. Schwartz, 1997 15. Welfare State, by Bent Greve, 1998 16. Socialism, by James C. Docherty, 1997 17. Bahá’í Faith, by Hugh C. Adamson and Philip Hainsworth, 1998 18. Taoism, by Julian F. Pas in cooperation with Man Kam Leung, 1998 19. Judaism, by Norman Solomon, 1998 20. Green Movement, by Elim Papadakis, 1998 21. Nietzscheanism, by Carol Diethe, 1999 22. Gay Liberation Movement, by Ronald J. Hunt, 1999 23. Islamic Fundamentalist Movements in the Arab World, Iran, and Turkey, by Ahmad S. -

Migrant Sufis and Shrines: a Microcosm of Islam Inthe Tribal Structure of Mianwali District

IJASOS- International E-Journal of Advances in Social Sciences, Vol.II, Issue 4, April 2016 MIGRANT SUFIS AND SHRINES: A MICROCOSM OF ISLAM INTHE TRIBAL STRUCTURE OF MIANWALI DISTRICT Saadia Sumbal Asst. Prof. Forman Christian College University Lahore, Pakistan, [email protected] Abstract This paper discusses the relationship between sufis and local tribal and kinship structures in the last half of eighteenth century to the end of nineteenth century Mianwali, a district in the south-west of Punjab. The study shows how tribal identities and local forms of religious organizations were closely associated. Attention is paid to the conditions in society which grounded the power of sufi and shrine in heterodox beliefs regarding saint‟s ability of intercession between man and God. Sufi‟s role as mediator between tribes is discussed in the context of changed social and economic structures. Their role as mediator was essentially depended on their genealogical link with the migrants. This shows how tribal genealogy was given precedence over religiously based meta-genealogy of the sufi-order. The focus is also on politics shaped by ideology of British imperial state which created sufis as intermediary rural elite. The intrusion of state power in sufi institutions through land grants brought sufis into more formal relations with the government as well as the general population. The state patronage reinforced their social authority and personal wealth and became invested with the authority of colonial state. Using hagiographical sources, factors which integrated pir and disciples in a spiritual bond are also discussed. This relationship is discussed in two main contexts, one the hyper-corporeality of pir, which includes his power and ability to move through time and space and multilocate himself to protect his disciples. -

Sunni – Shi`A Relations and the Implications for Belgium and Europe

FEARING A ‘SHIITE OCTOPUS’ SUNNI – SHI`A RELATIONS AND THE IMPLICATIONS FOR BELGIUM AND EUROPE EGMONT PAPER 35 FEARING A ‘SHIITE OCTOPUS’ Sunni – Shi`a relations and the implications for Belgium and Europe JELLE PUELINGS January 2010 The Egmont Papers are published by Academia Press for Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations. Founded in 1947 by eminent Belgian political leaders, Egmont is an independent think-tank based in Brussels. Its interdisciplinary research is conducted in a spirit of total academic freedom. A platform of quality information, a forum for debate and analysis, a melting pot of ideas in the field of international politics, Egmont’s ambition – through its publications, seminars and recommendations – is to make a useful contribution to the decision- making process. *** President: Viscount Etienne DAVIGNON Director-General: Marc TRENTESEAU Series Editor: Prof. Dr. Sven BISCOP *** Egmont - The Royal Institute for International Relations Address Naamsestraat / Rue de Namur 69, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Phone 00-32-(0)2.223.41.14 Fax 00-32-(0)2.223.41.16 E-mail [email protected] Website: www.egmontinstitute.be © Academia Press Eekhout 2 9000 Gent Tel. 09/233 80 88 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.academiapress.be J. Story-Scientia NV Wetenschappelijke Boekhandel Sint-Kwintensberg 87 B-9000 Gent Tel. 09/225 57 57 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.story.be All authors write in a personal capacity. Lay-out: proxess.be ISBN 978 90 382 1538 9 D/2010/4804/17 U 1384 NUR1 754 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publishers. -

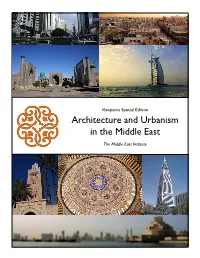

Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East

Viewpoints Special Edition Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East The Middle East Institute Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints is another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US relations with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org Cover photos, clockwise from the top left hand corner: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Imre Solt; © GFDL); Tripoli, Libya (Patrick André Perron © GFDL); Burj al Arab Hotel in Dubai, United Arab Emirates; Al Faisaliyah Tower in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; Doha, Qatar skyline (Abdulrahman photo); Selimiye Mosque, Edirne, Turkey (Murdjo photo); Registan, Samarkand, Uzbekistan (Steve Evans photo). -

Prophet Mohammed's (Pbuh)

1 2 3 4 ﷽ In the name Allah (SWT( the most beneficent Merciful INDEX Serial # Topic Page # 1 Forward 6 2 Names of Holy Qur’an 13 3 What Qur’an says to us 15 4 Purpose of Reading Qur’an in Arabic 16 5 Alphabetical Order of key words in Qura’nic Verses 18 6 Index of Surahs in Qur’an 19 7 Listing of Prophets referred in Qur’an 91 8 Categories of Allah’s Messengers 94 9 A Few Women mentioned in Qur’an 94 10 Daughter of Prophet Mohammed - Fatima 94 11 Mention of Pairs in Qur’an 94 12 Chapters named after Individuals in Qur’an 95 13 Prayers before Sleep 96 14 Arabic signs to be followed while reciting Qur’an 97 15 Significance of Surah Al Hamd 98 16 Short Stories about personalities mentioned in Qur’an 102 17 Prophet Daoud (David) 102 18 Prophet Hud (Hud) 103 19 Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) 103 20 Prophet Idris (Enoch) 107 21 Prophet Isa (Jesus) 107 22 Prophet Jacob & Joseph (Ya’qub & Yusuf) 108 23 Prophet Khidr 124 24 Prophet Lut (Lot) 125 25 Luqman (Luqman) 125 26 Prophet Musa’s (Moses) Story 126 27 People of the Caves 136 28 Lady Mariam 138 29 Prophet Nuh (Noah) 139 30 Prophet Sho’ayb (Jethro) 141 31 Prophet Saleh (Salih) 143 32 Prophet Sulayman Solomon 143 33 Prophet Yahya 145 34 Yajuj & Majuj 145 5 35 Prophet Yunus (Jonah) 146 36 Prophet Zulqarnain 146 37 Supplications of Prophets in Qur’an 147 38 Those cursed in Qur’an 148 39 Prophet Mohammed’s hadees a Criteria for Paradise 148 Al-Swaidan on Qur’an 149۔Interesting Discoveries of T 40 41 Important Facts about Qur’an 151 42 Important sayings of Qura’n in daily life 151 January Muharram February Safar March Rabi-I April Rabi-II May Jamadi-I June Jamadi-II July Rajab August Sh’aban September Ramazan October Shawwal November Ziqad December Zilhaj 6 ﷽ In the name of Allah, the most Merciful Beneficent Foreword I had not been born in a household where Arabic was spoken, and nor had I ever taken a class which would teach me the language. -

Download (564Kb)

CHAPTER THREE 3 BIOGRAPHY OF AL-FALIMBĀNĪ 3.1 Introduction This chapter discusses at length the biography of al-Falimbānī to the extent of the availability of the resources about him. It includes the following sections: on the dispute of his real name, his family background, his birth, his educational background, his teachers, his contemporaries, his works, the influence of scholars on him, his death and last but not least, his contribution. 3.2 His Name In spite of the fact that al-Falimbānī is one of the greatest Malay scholars in eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and having left many aspiring works, yet nothing much is known about this great scholar – neither the dates of his birth nor death has been established. All that is known is that he hailed from 1 Palembang. Even the exact name of his father remains unresolved and debated. Perhaps this scarcity of information2 that had forced P.Voorhoeve to write down only a few lines about al-Falimbāni in the Encyclopedia of Islam New Edition.3 1 Palembang is a city on the southern side of the Indonesian island of Sumatra. It is the capital of the Southern Sumatra province. The city was once the capital of the ancient, partly Buddhist kingdom of Srivijaya. 2 I beg to differ with Azra’s statement that “we have a rather complete account of his life and career…”, see Azra, Networks, 113. What we do have, however, are merely books written by him which have survived until these days, but as far as a complete biographical background of his is concerned, apart from in Salasilah and his short remarks here and there about himself in some of his works, we could hardly gather any other information concerning him. -

Carson Et Al.Pdf

The Brief Wondrous Tournament of WAO - Málà Yousufzai, served extra spicy Editors: Will Alston, Joey Goldman, James Lasker, Jason Cheng, Naveed Chowdhury, and Jonathan Luck, with writing assistance from Athena Kern and Shan Kothari. Packet by Carson et al TOSSUPS 1. This compound is released upon hydrolysis of compounds such as DMDM hydantoin [high-DAN- toe-in] and Quaternium-15. This compound is the lighter of the two monomers used to form melamine resin and Novolac. A pyridine derivative with no substituent at the 4 position is produced by the reaction of this compound with two beta-keto esters in the Hantzsch synthesis. An amine nucleophilically attacks this compound in the first step of a reaction which forms a beta-amino carbonyl, a compound also called a (*) Mannich base. The proton NMR spectrum of this compound consists of only one peak at around 9.6 ppm. In ChIP, this compound is used to cross-link DNA to proteins. It is the simplest and most common fixating agent used in biology experiments. Oxidizing methanol produces -- for 10 points -- what simplest aldehyde, which is used to preserve dead bodies? ANSWER: formaldehyde [or methanal or CH2O; do not accept or prompt on “methanol”] 2. In a story by this author, a character advises his cousin that one ought to beg from courting couples rather married ones. That story begins with its central character daydreaming about dodgem cars while his teacher talks about Masterman Ready and concludes with his cousin Bert trying to break them onto the title carousel at the Goose Fair. The family of the narrator of another story by this man entertains itself by muting the TV during politician’s speeches. -

Arte, Ciudad, Sociedad Improving

MÁSTER EN DISEÑO URBANO: ARTE, CIUDAD, SOCIEDAD IMPROVING THE CITY IMAGE OF RIYADH THROUGH STOREFRONT AND STREET SIGNAGE REDESIGN Tutor Dr. A. Remesar Author Sama AlMalik 1 IMPROVING THE CITY IMAGE OF RIYADH S. AlMalik THROUGH STOREFRONT AND STREET SIGNAGE REDESIGN 2 IMPROVING THE CITY IMAGE OF RIYADH S. AlMalik THROUGH STOREFRONT AND STREET SIGNAGE REDESIGN MÁSTER EN DISEÑO URBANO: ARTE, CIUDAD, SOCIEDAD IMPROVING THE CITY IMAGE OF RIYADH THROUGH STOREFRONT AND STREET SIGNAGE REDESIGN Tutor Dr. Antoni Remesar Author Sama AlMalik NUIB 15847882 Academic Year 2016-2017 Submitted in the support of the degree of Masters in Urban Design 3 IMPROVING THE CITY IMAGE OF RIYADH S. AlMalik THROUGH STOREFRONT AND STREET SIGNAGE REDESIGN 4 IMPROVING THE CITY IMAGE OF RIYADH S. AlMalik THROUGH STOREFRONT AND STREET SIGNAGE REDESIGN RESUMEN Las calles, barrios y ciudades de Arabia Saudita se encuentran en un estado de construcción permanente desde hace varias décadas, incentivando a la población de a adaptarse al cambio y la transformación, a estar abiertos a cambios constantes, a anticipar la magnitud de desarrollos futuros y a anhelar que el futuro se convierta en presente. El futuro, como se describe en la Visión 2030 del Príncipe Heredero Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud, promete tres objetivos principales: una economía próspera, una sociedad vibrante y una nación ambiciosa. Afortunadamente, para la capital, Riad, varios proyectos se están acercando a su finalización, haciendo cambios significativos en las calles, imagen y perfil de la ciudad. Esto configura cómo los ciudadanos interactúan con toda la ciudad, cómo se integran y reconocen nuevas calles, edificios y distritos. -

The Profession: Leader, Ruler, Cleric, Guide, Authority, Preacher, Minister

Nancy Khalil (Oct 6) Title: The Profession: Leader, Ruler, Cleric, Guide, Authority, Preacher, Minister, Mufti, Pir, Murshid, Amir, Shaykh, Da'ee; Imam Abstract: Our terminology for Muslim religious leadership is quite ambiguous across time and space, and we have a range of words such as imam, ‘alim, shaykh, mawla, and mufti, da’ee that are often conflated. The skill set, and consequently societal contribution, was historically based on individual talents and not on institutionally, or state, defined professions and job responsibilities. Why did the profession of the imam evolve into a distinctive position, one that includes leading five daily prayers, but also giving occasional mentoring and advising to community members? How did the position become practical and applied? Why did it shift away from being a natural service available in mosques to a position that entailed marrying and divorcing congregants, advising and counseling, youth work, representing and political relationship building among many other things? This chapter explores some of the history of the imam in current Muslim imagination along with more contemporary expressions of the expectation of an imam working in a U.S. mosque today. Dr. Khaled Fahmy (Oct 20) Title: Siyāsa, fiqh and shari‘a in 19th-century Egyptian law Abstract: Within classical Islamic political discourse, siyasa refers to the discretionary authority of the ruler and his officials, one which is exercised outside the framework of shariʿa. Scholars of Islamic law, both in the West and in the Islamic world, have tended to agree with Muslim jurists, the fuqahā’, that this discretionary authority co-existed in a tense manner with the authority of the fuqahā’ and with the role and function of the qāḍī, the sharī‘a court judge. -

Islamska Misao

ISLAMSKA MISAO Osnivač i izdavač: Fakultet za islamske studije, Novi Pazar Za izdavača: prof. dr. Enver Gicić Glavni urednik: prof. dr. Enver Gicić Pomoćnik urednika: prof. dr. Hajrudin Balić Redakcija: prof. dr. Sulejman Topoljak prof. dr. Metin Izeti doc. dr. Haris Hadžić prof. dr. Admir Muratović prof. dr. hfz. Almir Pramenković Šerijatski recenzent: prof. dr. hfz. Almir Pramenković Lektor: Binasa Spahović Tehničko uređenje: Media centar Islamske zajednice, Novi Pazar Štampa: El-Kelimeh, Beograd Tiraž: 500 primjeraka Adresa redakcije: Fakultet za islamske studije ul. Rifata Burdževića 1 36300 Novi Pazar CIP - Katalogizacija u publikaciji Narodna biblioteka Srbije, Beograd 378:28 ISLAMSKA misao : godišnjak Fakulteta za islamske studije u Novom Pazaru / glavni urednik Almir Pramenković . - 2007, br. 1 - . Novi Pazar (Gradski trg) : Fakultet za islamske studije, 2007- (Beograd : El-Kelimeh). -24 cm Godišnje ISSN 1452-9580 = Islamska misao (Novi Pazar) COBISS.SR-ID 141771532 9 ISLAMSKA MISAO Godišnjak Fakulteta za islamske studije Novi Pazar Novi Pazar, 2016. SADRŽAJ ISLAMSKA MISAO • NOVI PAZAR, 2016 • BROJ 9 SADRŽAJ Uvod .................................................................................................................................7 Muftija Muamer ef. Zukorlić TERORKRATIJA IZMEĐU ISILA I AJFELA ..................................................................11 Hfz. prof. dr. Almir Pramenković STANJE IMANA - POVEĆANJE I SMANJENJE U SVJETLU KUR’ANA I SUNNETA ...............................................................................29