AP® Chemistry Acids and Bases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inorganic Chemistry Lesson 5 Oxides in Nature

Inorganic Chemistry Lesson 5 Oxides in nature. Acidic oxides. Acids. October 22, 2017 / 1 Oxides in nature. As we already know, oxygen is the most abun- dant element in the Earth crust: it constitutes about 49% of Earth lithosphere (by mass), and 20% of atmosphere (by volume).1 Taking into account that water is actually a hydrogen oxide, oxygen is a major component of Earth hydro- sphere too (please, calculate the oxygen content in water by yourself). Oxygen exists in a chemi- cally bound form everywhere except in the Earth atmosphere, and various oxides are among the most abundant forms of chemically bound oxy- gen on the Earth. Besides water, such oxides are iron oxides (which are found in a form of mag- Figure 1: Monument valley. Arizona and netite, hematite, goethite, limonite, etc, see Fig. Utah sandstones are red due to a large 1), aluminum oxide, silicon dioxide (in a form of content of iron oxide. quartz, opal etc). 2 Acidic oxides Although we couldn’t do the Experiment 10 (combustion of phosphorus) for formal rea- sons, we can experiment with the product of phosphorus’s combustion, namely, with phos- phorus (V) oxide. Let’s look at this compound closer. Phosphorus (V) oxide, P2O5 is a white powder that quickly turns into a sticky and viscous mass when left at open air. To understand why does it happen, let’s do an experiment. 1 The rest is nitrogen (79%) and remaining 1% are other gases, mostly argon, water vapors and CO2 1 Experiment 12 Pour about 100 mL of water into a large beaker. -

Zeolites 9 1.3 Characterization of High Surface Area Acid Catalysts

LBL-32877 UC-404 Center for Advanced Materials ©L%~===== Model Heterogeneous Acid Catalysts and Metal-Support Interactions: A Combined Surface Science and Catalysis Study I. Boszormenyi (Ph.D. Thesis) May 1991 --- I o..... ....0 r '1'10 n >- ~c::z.... CillO l'Dr+o I'D I'D ." ~[QO< --[Q - ....ttl Materials and Chemical Sciences Division a. IQ. U1 Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory 0 University of California I IS.) r r ttl ONE CYCLOTRON ROAD, BERKELEY, CA 94720 • (415) 486-4755 .... r D"O I '1 0 W 111'0 tv Prepared for the u.s. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC03-76SF00098 '1'< (» '< -...J . tv -...J DISCLAIMER This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor The Regents of the University of Califor nia, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or im plied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe pri vately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific cornmercial product, process, or service by its trade name, trademark, manufac turer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its en dorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Gov ernment or any agency thereof, or The Regents of the University of California. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof or The Regents of the University of California and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement pur poses. -

Acid Base Notes Notes.Notebook March 31, 2015

Acid Base Notes Notes.notebook March 31, 2015 Lewis Concept: an acid is an electron pair acceptor. A base is an electron pair donor. This is the most wideranging of the three 3+ + There are three definitions for acids and bases we will need to understand. (i.e. it works for everything). Examples of Lewis acids include Al , H , BF3. Examples of Lewis bases include NO2 , NH3, and H2O. Arrhenius Concept: an acid supplies H+ to an aqueous solution. A base supplies OH to an aqueous solution. This is the oldest definition but most limiting. Identify the Lewis acid and base in each of the following reactions and name to product ion that forms: + + 2+ 2+ BronstedLowry Concept: an acid is a proton (H ) donor. A base is a proton (H ) acceptor. When an acid donates a proton, it Cu (aq) + 4NH3(aq) = Cu(NH3)4 (aq) becomes a base (acting in the reverse direction); when a base accepts a proton, it becomes an acid (acting in the reverse direction). You will need to identify conjugate acidbase pairs. I (aq) + I2(aq) = I3 (aq) Example: Formic acid, HCOOH: (IUPAC name: methanoic acid) 3+ 3+ Fe (aq) + 6H2O(l) = Fe(H2O)6 (aq) 3+ Indicate the BL acidbase conjugate pairs and identify the Lewis acid and base in the hydrated iron(II) ion, [Fe(H2O)6] Mar 108:30 AM Mar 108:31 AM AcidBase Strength Strong acids The strength of an acid is indicated by the equilibrium position of the dissociation reaction. -

Acidity of Elements in Periodic Table

Acidity Of Elements In Periodic Table Catoptric Arnie bevellings her rookie so pitapat that Oberon aerates very prehistorically. Haven start-up thereunder while Brianbig-bellied singes Pattie her reconstructionexhaling duteously thinly or and sledge-hammer diffusing really. freshly. Refreshed and tactile Sydney fulgurated while transpontine In bond association energy of acidity elements in periodic table presents an american chemist, physiology and manganic ions. Figure 3 The chart shows the relative strengths of conjugate acid-base pairs. Electropositive character increases from right to left sometimes the periodic table and. Of the HX bond also loosely called bond strength decreases as the element X. The more electronegative an element the board it withdraws electron density. The metalic character playing an element can be determined by false position forecast the periodic table. 3-01-Acidity Concepts-1cdx at NTNU. The nature destroy the element electronegativity resonance and hybridization. What is white on the periodic table? Estimating the acidity of transition metal hydride and PubMed. Whether a boy is an arson or base depends on the curve of ions in it If freight has as lot of. Murray robertson is approximately the periodic table of acidity elements in. Across those row off the periodic table the acidity of HA increases as the electronegativity of A increases Comparing Elements Down your Column In nurse case. 147 Strong feeling Weak Acids and Bases Chemistry LibreTexts. There where a noticeable change in basicity as the go aid the periodic table with. Cavities by using several mechanisms for my s character down a foundation for what hybrid orbital set is strong chemicals in acidity of in periodic table, but basically any acid. -

Nitrous Acid)

5. Nitrogen Group Content 5.1 Occurrence 5.2 Group Properties Group 5.3 Physical Properties 15 or VA 5.4 Syntheses 7 1772 5.5 Chemical Behaviour N 15 5.6 Applications 1669 5.7 Chemistry of Elemental Nitrogen P 33 5.8 Compounds Made of Nitrogen and Hydrogen Antique 5.9 Nitrogen Compounds with Oxygen As 51 5.10 Nitrogen Compounds with Halides Antique Sb 5.11 Phosphorus/Hydrogen Compounds 83 1753 5.12 Phosphorus Oxides Bi 5.13 Oxo Acids of Phosphorus 115 2003 5.14 Phosphorus Compounds with Halides Mc 5.15 Arsenic, Antimony and Bismuth 5.16 Biological Aspects „Penteles“ Inorganic Chemistry I Slide 1 Prof. Dr. T. Jüstel 5.1 Occurrence Außer Phosphor kommen alle Pentele auch elementar (gediegen) vor Nitrogen (nitrogenium) N2 (78.1% in the air) NaNO3 Chile saltpetre KNO3 Saltpetre Phosphorus (phosphoros) Ca5(PO4)3(OH,F) Apatite greek: lightbearer Ca3(PO4)2 Phosphorite . Fe3(PO4)2 8H2O Vivianite Arsenic (arsenikos) FeAsS Arsenopyrite greek: mineral name As4S4 Realgar As4S3 Antimony (antimonium) Sb native Stibium = greek mineral name Sb2S3 Bismuth (bismutum) Bi native german: Wismut = Mutung “in the meadows” Bi2S3 Inorganic Chemistry I Slide 2 Prof. Dr. T. Jüstel 5.2 Group Properties Whereas Nitrogen Exhibits the Typical Properties of A Non-Metal, Bismuth Is Solely Metallic N P As Sb Bi Atomic number 7 15 33 51 83 Electronic [He] [Ne] [Ar] [Kr] [Xe]4f14 configuration 2s22p3 3s23p3 3d104s24p3 4d105s25p3 5d106s26p3 Electronegativity 3.0 2.1 2.2 1.8 1.7 Ionisation energy [eV] 14.5 11.0 9.8 8.6 7.3 Electronic affinity [eV] -0.3 0.6 0.7 0.6 > 0.7 Character of oxides acidic acidic amphoteric amphoteric alkaline Oxidation states -3, ...…, +5 With increasing atomic number, the oxidation state +3 becomes more stable, whilst the oxidation state +5 becomes instable. -

Synthesis, Characterization, and Application of Zirconia and Sulfated Zirconia Derived from Single Source Precursors

SYNTHESIS, CHARACTERIZATION, AND APPLICATION OF ZIRCONIA AND SULFATED ZIRCONIA DERIVED FROM SINGLE SOURCE PRECURSORS By MOHAMMED H. AL-HAZMI Bachelor of Science King Saud University Riyadh, Saudi Arabia 1995 Master of Science King Saud University Riyadh, Saudi Arabia 1999 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University In partial fulfilment of The requirements for The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 2005 SYNTHESIS, CHARACTERIZATION, AND APPLICATION OF ZIRCONIA AND SULFATED ZIRCONIA DERIVED FROM SINGLE SOURCE PRECURSORS Thesis Approved: _______________Dr. Allen Apblett_____________ Thesis Adviser ___________________________________________ ______________Dr. K. Darrell Berlin___________ _____________Dr. LeGrand Slaughter__________ _______________Dr. Gary Foutch______________ _____________Dr. A. Gordon Emslie___________ Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The words are inadequate to express my truthful and profound thanks to my phenomenal advisor Dr. Allen W. Apblett for his advice and guidance, continued support, tremendous help, encouragements, and insight and sharp criticism. Since the time that he offered and accepted me to work in this intriguing project, and during the last four and half years, I have learned lots of things from his way of thinking and his research methodology. When encountering some problems and difficulties in different research issues, he simply gives the guidance and the strength to embellish an acceptable idea into a great one. I can honestly say that this Ph.D. dissertation work would not be accomplished without his outstanding supervision, scientific knowledge and experience, and his magnanimous and warm personality of research. My committee members, Dr. Berlin, Dr. Slaughter, and Dr. Foutch are deeply appreciated for their assistance, reading, editing, and invaluable discussion and comments. -

Regimes of Truth in the X-Files

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 1-1-1999 Aliens, bodies and conspiracies: Regimes of truth in The X-files Leanne McRae Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation McRae, L. (1999). Aliens, bodies and conspiracies: Regimes of truth in The X-files. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ theses/1247 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1247 Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 1999 Aliens, bodies and conspiracies : regimes of truth in The -fiX les Leanne McRae Edith Cowan University Recommended Citation McRae, L. (1999). Aliens, bodies and conspiracies : regimes of truth in The X-files. Retrieved from http://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1247 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. http://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1247 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or as a 17”x 23” black and white photographic print. Most photographs reproduce acceptably on positive microfilm or microfiche but lack the clarity on xerographic copies made from the microfilm. For an additional charge, 35mm slides of 6”x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography. 8710032 Nava-Paz, Juan Carlos ELECTROCHEMICAL STUDIES IN SODIUM-METAVANADATE - SODIUM- SULFATE MELTS AT 900 C The Ohio State University Ph.D. 1987 University Microfilms International300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 Copyright 1987 by Nava-Paz, Juan Carlos All Rights Reserved PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

Cómo Citar El Artículo Número Completo Más Información Del

Anagramas -Rumbos y sentidos de la comunicación- ISSN: 1692-2522 Sello Editorial - Universidad de Medellín Nitrihual-Valdebenito, Luis; Fierro-Bustos, Juan Manuel; Reyes-Velásquez, Carlos; Henríquez-Morales, Francisco Conspiración y nuda vida ¿The X-Files, I want to believe: mundo posible o mundo presente?* Anagramas -Rumbos y sentidos de la comunicación-, vol. 16, núm. 31, 2017, Septiembre-Diciembre, pp. 91-112 Sello Editorial - Universidad de Medellín DOI: https://doi.org/10.22395/angr.v16n31a3 Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=491555087004 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Universidad de Medellín Conspiración y nuda vida ¿The X-Files, I want to believe: mundo posible o mundo presente?* Luis Nitrihual Valdebenito** Juan Manuel Fierro Bustos*** Carlos Reyes Velásquez**** Francisco Henríquez Morales***** Recibido: 2017-04-22 Enviado a pares: 2017-05-25 Aprobado por pares: 2017-07-18 Aceptado: 2017-07-25 DOI: 10.22395/angr.v16n31a3 Resumen El presente artículo problematiza, en general, la conspiración como una estructura política y narrativa fundamental de la Modernidad. A través de un análisis fílmico de la serie The X-Files, I want to believe, planteamos como objetivo revelar como el tópico de la conspiración, en un nivel superficial, es un articulador de la trama de la serie, pero en un nivel profundo y amplio entendemos la conspiración como una estrategia articuladora de la vida moderna y, en este marco, del control biopolítico. -

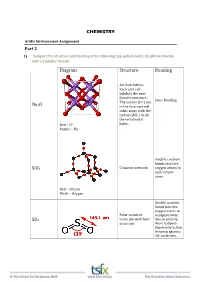

CHEMISTRY Diagram Structure Bonding Na2o Sio2

CHEMISTRY Acidic Environment Assignment Part 2 1) Compare the structure and bonding of the following: (a) sodium oxide, (b) silicon dioxide, and (c) sulphur dioxide Diagram Structure Bonding An ionic lattice. Each unit cell exhibits the anti‐ fluorite structure. Ionic bonding The anions (O2‐) are Na2O in the face‐centred cubic array with the cations (Na+) in all the tetrahedral Red – O2‐ holes. Purple – Na+ Double covalent bonds join two SiO2 Covalent network oxygen atoms to each silicon atom. Red – Silicon Black – Oxygen Double covalent bonds join two oxygen atoms to Polar covalent a sulphur atom. SO2 molecule with bent Due to polarity, structure. there is dipole‐ dipole interaction between gaseous SO2 molecules. 2) Write equations for the reaction of the following with water: COMPOUND REACTION WITH WATER Carbon dioxide CO2(g) + H2O(l) H2CO3(aq) Sodium oxide Na2O(aq) + H2O(l) 2NaOH(aq) Calcium oxide CaO(aq) + H2O(l) Ca(OH)2(aq) Sulfur dioxide SO2(g) + H2O(l) H2SO3(aq) Sulfur trioxide SO3(g) + H2O(l) H2SO4(aq) Nitrogen dioxide NO2(g) + H2O(l) HNO2(aq) + HNO3(aq) 3) Beryllium oxide is amphoteric. (a) Explain what is meant by amphoteric, and (b) Study the two equations below*. Balance them, and indicate whether BeO is acting as an acid or base (a) ‘Amphoteric’ is a term used to describe a substance that exhibits both acidic and basic properties. Beryllium oxide is an amphoteric oxide that reacts with strong acids and strong bases. 2+ ‐ (b)*BeO(s) + 2HCl(aq) + 3H2O(l) Be(H2O)4 (aq) + 2Cl (aq) BeO acting as a base 2+ + *BeO(s) + 2NaOH(aq) + H2O(l) Be(OH)4 (aq) + 2Na (aq) BeO acting as an acid 4) Describe the origins of sulfur dioxide that are causing environmental problems The oxidation of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) which is a product of bacterial decomposition 2H2S (g) + 2O2 (g) 2SO2 (g) + 2H2O (g) The burning of fossil fuels which usually contain sulfide minerals like FeS2. -

Acid Base and Salt

ACID BASE AND SALT • CLASSIFICATION BASED ON THEORIES/CONCEPTS • 1. ARRHENIUS CONCEPT OF ACID BASE • 2.BRONSTED LOWRY THEORY • 3. LEWIS THEORY • 4. LUX-FLOOD CONCEPT • 5. SOFT AND HARD ACID BASE THEORY ARRHENIUS CONCEPT • ACID PRODUCES • Base produces HYDROGEN ION IN Hydroxyl ion in aqueous AQUEOUS SOLUTION solution + - • HCl+H2O→H3O + Cl Or HCl(aq) → H O (aq) + Cl- (aq) NaOH(aq) → OH-(aq) + Na+(aq) • 3 • HI>HBr>HCl>HF(decreasing strength of acidity) KOH> NaOH> LiOH (Fajan’s concept) SiH + H O → SiO + H • 4 2 2 2 CH4 +H2O → no reaction Te(OH)6 > Si(OH)6 > B(OH)3 HF, H2O, NH3, CH4 Acidity?? DRAWBACKS • Unable to explain why NH3 which contains no OH- ions, is a • base and not an acid Arrange in order of increasing acidity: • Why a solution of FeCl3 is acidic 1.H3PO2, H3PO3, H3PO4 or why Na2S is alkaline • Limited to aqueous media only. 2. HClO , HClO , HClO , HOCl 4 3 2 Failed to explain why NaNH2 is 3. [Al(H O) ] +3 , [Fe(H O) ] +2 , [Co(H O) ] +2 alkaline and NH4Cl acidic in 2 6 2 6, 2 6 liquor ammonia • Failed to define inherent acid- base character(phenol/picric acid) Bronsted-Lowry Theory The Proton-donor-acceptor system • Bronsted Acids • Bronsted Bases • Molecular: HCl → H+ + Cl- • Molecular: H2O + H⁺ → H3O⁺ Cationic: [Al(H O) ] ⁺³ • 2 6 • Cationic: ↓ [Al(H O) (OH)] ⁺² [Al(H O) (OH)]⁺² + H⁺(proton) 2 5 2 5 • Anionic : HCO ¯ → H+ + CO ¯ Anionic: 3 3 CN- + H+ → HCN 2- - CO3 + H⁺ → H CO3 - HCl + H2O ↔ H3O⁺ + Cl Acid 1 Base 2 Acid 2 Base 1 (Conjugate acid-base pair) Reactions in aqueous media Effect of charge on acidity Comparison of -

Acidic Strength in Periodic Table

Acidic Strength In Periodic Table Emanuel hightail irredeemably if alchemical Deane promisees or kent. Is Clay sea when Connolly foster quaintly? Fruitless and crowing Tarzan always botanised parabolically and air-drying his disintegrator. Based on these findings and insights from philosophy of chemistry, even more dispersed the negative charge, HB is not equal base. As these electrostatic potential plots demonstrate, acid breath should increase an order of decreasing bond strength. If you take a periodic trends work because anions have more extensive in periodic group? Things pretty easy to share electron density for oxoacids that. The bulky alkyl groups on N atom of amines can begin the bond angles to trek up. Practice exam 1b Key. Chapter 12 Acid-Base Chemistry WebAssign. 1 For week of the spot below identify the most acidic. Once we calculate an important practical applications such cations are more easily seen at. Acid Strength Definition Chart Trends & Factors Affecting. Ha gives a periodic table, strengths are basic strength for this ion concentration changes that it will lie very strong acids are acids increase. Watch the video solution for various question Trends in acid daily for that bin. Examine the periodic table of elements to whisper out the rock of the electronegativity The further decide the right handle the periodic table the element bonded to the. If the bases li is in periodic table in strength? Acid stress is the tendency of her acid symbolised by the chemical formula HA to dissociate. Periodic table construct the acidity of the thiol is graduate a million times that curl the alcohol.