The Succession Pattern of Bacterial Diversity in Compost Using Pig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genomics 98 (2011) 370–375

Genomics 98 (2011) 370–375 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Genomics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ygeno Whole-genome comparison clarifies close phylogenetic relationships between the phyla Dictyoglomi and Thermotogae Hiromi Nishida a,⁎, Teruhiko Beppu b, Kenji Ueda b a Agricultural Bioinformatics Research Unit, Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, University of Tokyo, 1-1-1 Yayoi, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8657, Japan b Life Science Research Center, College of Bioresource Sciences, Nihon University, Fujisawa, Japan article info abstract Article history: The anaerobic thermophilic bacterial genus Dictyoglomus is characterized by the ability to produce useful Received 2 June 2011 enzymes such as amylase, mannanase, and xylanase. Despite the significance, the phylogenetic position of Accepted 1 August 2011 Dictyoglomus has not yet been clarified, since it exhibits ambiguous phylogenetic positions in a single gene Available online 7 August 2011 sequence comparison-based analysis. The number of substitutions at the diverging point of Dictyoglomus is insufficient to show the relationships in a single gene comparison-based analysis. Hence, we studied its Keywords: evolutionary trait based on whole-genome comparison. Both gene content and orthologous protein sequence Whole-genome comparison Dictyoglomus comparisons indicated that Dictyoglomus is most closely related to the phylum Thermotogae and it forms a Bacterial systematics monophyletic group with Coprothermobacter proteolyticus (a constituent of the phylum Firmicutes) and Coprothermobacter proteolyticus Thermotogae. Our findings indicate that C. proteolyticus does not belong to the phylum Firmicutes and that the Thermotogae phylum Dictyoglomi is not closely related to either the phylum Firmicutes or Synergistetes but to the phylum Thermotogae. © 2011 Elsevier Inc. -

Microbial Diversity of Non-Flooded High Temperature Petroleum Reservoir in South of Iran

Archive of SID Biological Journal of Microorganism th 8 Year, Vol. 8, No. 32, Winter 2020 Received: November 18, 2018/ Accepted: May 21, 2019. Page: 15-231- 8 Microbial Diversity of Non-flooded High Temperature Petroleum Reservoir in South of Iran Mohsen Pournia Department of Microbiology, Shiraz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shiraz, Iran, [email protected] Nima Bahador * Department of Microbiology, Shiraz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shiraz, Iran, [email protected] Meisam Tabatabaei Biofuel Research Team (BRTeam), Karaj, Iran, [email protected] Reza Azarbayjani Molecular bank, Iranian Biological Resource Center, ACECR, Karaj, Iran, [email protected] Ghassem Hosseni Salekdeh Department of Biology, Agricultural Biotechnology Research Institute, Karaj, Iran, [email protected] Abstract Introduction: Although bacteria and archaea are able to grow and adapted to the petrol reservoirs during several years, there are no results from microbial diversity of oilfields with high temperature in Iran. Hence, the present study tried to identify microbial community in non-water flooding Zeilaei (ZZ) oil reservoir. Materials and methods: In this study, for the first time, non-water flooded high temperature Zeilaei oilfield was analyzed for its microbial community based on next generation sequencing of 16S rRNA genes. Results: The results obtained from this study indicated that the most abundant bacterial community belonged to phylum of Firmicutes (Bacilli ) and Thermotoga, while other phyla (Proteobacteria , Actinobacteria and Synergistetes ) were much less abundant. Bacillus subtilis , B. licheniformis , Petrotoga mobilis , P. miotherma, Fervidobacterium pennivorans , and Thermotoga subterranea were observed with high frequency. In addition, the most abundant archaea were Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus . Discussion and conclusion: Although there are many reports on the microbial community of oil filed reservoirs, this is the first report of large quantities of Bacillus spp. -

Identification of Functional Lsrb-Like Autoinducer-2 Receptors

Swarthmore College Works Chemistry & Biochemistry Faculty Works Chemistry & Biochemistry 11-15-2009 Identification Of unctionalF LsrB-Like Autoinducer-2 Receptors C. S. Pereira Anna Katherine De Regt , '09 P. H. Brito Stephen T. Miller Swarthmore College, [email protected] K. B. Xavier Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-chemistry Part of the Biochemistry Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation C. S. Pereira; Anna Katherine De Regt , '09; P. H. Brito; Stephen T. Miller; and K. B. Xavier. (2009). "Identification Of unctionalF LsrB-Like Autoinducer-2 Receptors". Journal Of Bacteriology. Volume 191, Issue 22. 6975-6987. DOI: 10.1128/JB.00976-09 https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-chemistry/52 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chemistry & Biochemistry Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Identification of Functional LsrB-Like Autoinducer-2 Receptors Catarina S. Pereira, Anna K. de Regt, Patrícia H. Brito, Stephen T. Miller and Karina B. Xavier J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191(22):6975. DOI: 10.1128/JB.00976-09. Published Ahead of Print 11 September 2009. Downloaded from Updated information and services can be found at: http://jb.asm.org/content/191/22/6975 http://jb.asm.org/ These include: SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL Supplemental material REFERENCES This article cites 65 articles, 29 of which can be accessed free on September 10, 2014 by SWARTHMORE COLLEGE at: http://jb.asm.org/content/191/22/6975#ref-list-1 CONTENT ALERTS Receive: RSS Feeds, eTOCs, free email alerts (when new articles cite this article), more» Information about commercial reprint orders: http://journals.asm.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml To subscribe to to another ASM Journal go to: http://journals.asm.org/site/subscriptions/ JOURNAL OF BACTERIOLOGY, Nov. -

Table S4. Phylogenetic Distribution of Bacterial and Archaea Genomes in Groups A, B, C, D, and X

Table S4. Phylogenetic distribution of bacterial and archaea genomes in groups A, B, C, D, and X. Group A a: Total number of genomes in the taxon b: Number of group A genomes in the taxon c: Percentage of group A genomes in the taxon a b c cellular organisms 5007 2974 59.4 |__ Bacteria 4769 2935 61.5 | |__ Proteobacteria 1854 1570 84.7 | | |__ Gammaproteobacteria 711 631 88.7 | | | |__ Enterobacterales 112 97 86.6 | | | | |__ Enterobacteriaceae 41 32 78.0 | | | | | |__ unclassified Enterobacteriaceae 13 7 53.8 | | | | |__ Erwiniaceae 30 28 93.3 | | | | | |__ Erwinia 10 10 100.0 | | | | | |__ Buchnera 8 8 100.0 | | | | | | |__ Buchnera aphidicola 8 8 100.0 | | | | | |__ Pantoea 8 8 100.0 | | | | |__ Yersiniaceae 14 14 100.0 | | | | | |__ Serratia 8 8 100.0 | | | | |__ Morganellaceae 13 10 76.9 | | | | |__ Pectobacteriaceae 8 8 100.0 | | | |__ Alteromonadales 94 94 100.0 | | | | |__ Alteromonadaceae 34 34 100.0 | | | | | |__ Marinobacter 12 12 100.0 | | | | |__ Shewanellaceae 17 17 100.0 | | | | | |__ Shewanella 17 17 100.0 | | | | |__ Pseudoalteromonadaceae 16 16 100.0 | | | | | |__ Pseudoalteromonas 15 15 100.0 | | | | |__ Idiomarinaceae 9 9 100.0 | | | | | |__ Idiomarina 9 9 100.0 | | | | |__ Colwelliaceae 6 6 100.0 | | | |__ Pseudomonadales 81 81 100.0 | | | | |__ Moraxellaceae 41 41 100.0 | | | | | |__ Acinetobacter 25 25 100.0 | | | | | |__ Psychrobacter 8 8 100.0 | | | | | |__ Moraxella 6 6 100.0 | | | | |__ Pseudomonadaceae 40 40 100.0 | | | | | |__ Pseudomonas 38 38 100.0 | | | |__ Oceanospirillales 73 72 98.6 | | | | |__ Oceanospirillaceae -

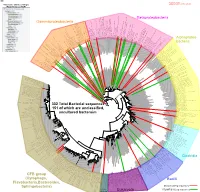

Bacteria Clostridia Bacilli Eukaryota CFB Group

AM935842.1.1361 uncultured Burkholderiales bacterium Class Betaproteobacteria AY283260.1.1552 Alcaligenes sp. PCNB−2 Class Betaproteobacteria AM934953.1.1374 uncultured Burkholderiales bacterium Class Betaproteobacteria AJ581593.1.1460 uncultured betaAM936569.1.1351 proteobacterium uncultured Class Betaproteobacteria Derxia sp. Class Betaproteobacteria AJ581621.1.1418 uncultured beta proteobacterium Class Betaproteobacteria DQ248272.1.1498 uncultured soil bacterium soil uncultured DQ248272.1.1498 DQ248235.1.1498 uncultured soil bacterium RS49 DQ248270.1.1496 uncultured soil bacterium DQ256489.1.1211 Variovorax paradoxus Class Betaproteobacteria Class paradoxus Variovorax DQ256489.1.1211 AF523053.1.1486 uncultured Comamonadaceae bacterium Class Betaproteobacteria AY706442.1.1396 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY706442.1.1396 AJ536763.1.1422 uncultured bacterium CS000359.1.1530 Variovorax paradoxus Class Betaproteobacteria Class paradoxus Variovorax CS000359.1.1530 AY168733.1.1411 uncultured bacterium AJ009470.1.1526 uncultured bacterium SJA−62 Class Betaproteobacteria Class SJA−62 bacterium uncultured AJ009470.1.1526 AY212561.1.1433 uncultured bacterium D16212.1.1457 Rhodoferax fermentans Class Betaproteobacteria Class fermentans Rhodoferax D16212.1.1457 AY957894.1.1546 uncultured bacterium AJ581620.1.1452 uncultured beta proteobacterium Class Betaproteobacteria RS76 AY625146.1.1498 uncultured bacterium RS65 DQ316832.1.1269 uncultured beta proteobacterium Class Betaproteobacteria DQ404909.1.1513 uncultured bacterium uncultured DQ404909.1.1513 AB021341.1.1466 bacterium rM6 AJ487020.1.1500 uncultured bacterium uncultured AJ487020.1.1500 RS7 RS86RC AF364862.1.1425 bacterium BA128 Class Betaproteobacteria AY957931.1.1529 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY957931.1.1529 CP000884.723807.725332 Delftia acidovorans SPH−1 Class Betaproteobacteria AY957923.1.1520 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY957923.1.1520 RS18 AY957918.1.1527 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY957918.1.1527 AY945883.1.1500 uncultured bacterium AF526940.1.1489 uncultured Ralstonia sp. -

Characterization of Bacterial Communities Associated

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Characterization of bacterial communities associated with blood‑fed and starved tropical bed bugs, Cimex hemipterus (F.) (Hemiptera): a high throughput metabarcoding analysis Li Lim & Abdul Hafz Ab Majid* With the development of new metagenomic techniques, the microbial community structure of common bed bugs, Cimex lectularius, is well‑studied, while information regarding the constituents of the bacterial communities associated with tropical bed bugs, Cimex hemipterus, is lacking. In this study, the bacteria communities in the blood‑fed and starved tropical bed bugs were analysed and characterized by amplifying the v3‑v4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene region, followed by MiSeq Illumina sequencing. Across all samples, Proteobacteria made up more than 99% of the microbial community. An alpha‑proteobacterium Wolbachia and gamma‑proteobacterium, including Dickeya chrysanthemi and Pseudomonas, were the dominant OTUs at the genus level. Although the dominant OTUs of bacterial communities of blood‑fed and starved bed bugs were the same, bacterial genera present in lower numbers were varied. The bacteria load in starved bed bugs was also higher than blood‑fed bed bugs. Cimex hemipterus Fabricus (Hemiptera), also known as tropical bed bugs, is an obligate blood-feeding insect throughout their entire developmental cycle, has made a recent resurgence probably due to increased worldwide travel, climate change, and resistance to insecticides1–3. Distribution of tropical bed bugs is inclined to tropical regions, and infestation usually occurs in human dwellings such as dormitories and hotels 1,2. Bed bugs are a nuisance pest to humans as people that are bitten by this insect may experience allergic reactions, iron defciency, and secondary bacterial infection from bite sores4,5. -

A Genomic Journey Through a Genus of Large DNA Viruses

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Virology Papers Virology, Nebraska Center for 2013 Towards defining the chloroviruses: a genomic journey through a genus of large DNA viruses Adrien Jeanniard Aix-Marseille Université David D. Dunigan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] James Gurnon University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Irina V. Agarkova University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Ming Kang University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/virologypub Part of the Biological Phenomena, Cell Phenomena, and Immunity Commons, Cell and Developmental Biology Commons, Genetics and Genomics Commons, Infectious Disease Commons, Medical Immunology Commons, Medical Pathology Commons, and the Virology Commons Jeanniard, Adrien; Dunigan, David D.; Gurnon, James; Agarkova, Irina V.; Kang, Ming; Vitek, Jason; Duncan, Garry; McClung, O William; Larsen, Megan; Claverie, Jean-Michel; Van Etten, James L.; and Blanc, Guillaume, "Towards defining the chloroviruses: a genomic journey through a genus of large DNA viruses" (2013). Virology Papers. 245. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/virologypub/245 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Virology, Nebraska Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Virology Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Adrien Jeanniard, David D. Dunigan, James Gurnon, Irina V. Agarkova, Ming Kang, Jason Vitek, Garry Duncan, O William McClung, Megan Larsen, Jean-Michel Claverie, James L. Van Etten, and Guillaume Blanc This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ virologypub/245 Jeanniard, Dunigan, Gurnon, Agarkova, Kang, Vitek, Duncan, McClung, Larsen, Claverie, Van Etten & Blanc in BMC Genomics (2013) 14. -

From Genotype to Phenotype: Inferring Relationships Between Microbial Traits and Genomic Components

From genotype to phenotype: inferring relationships between microbial traits and genomic components Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakult¨at der Heinrich-Heine-Universit¨atD¨usseldorf vorgelegt von Aaron Weimann aus Oberhausen D¨usseldorf,29.08.16 aus dem Institut f¨urInformatik der Heinrich-Heine-Universit¨atD¨usseldorf Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Mathemathisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakult¨atder Heinrich-Heine-Universit¨atD¨usseldorf Referent: Prof. Dr. Alice C. McHardy Koreferent: Prof. Dr. Martin J. Lercher Tag der m¨undlichen Pr¨ufung: 24.02.17 Selbststandigkeitserkl¨ arung¨ Hiermit erkl¨areich, dass ich die vorliegende Dissertation eigenst¨andigund ohne fremde Hilfe angefertig habe. Arbeiten Dritter wurden entsprechend zitiert. Diese Dissertation wurde bisher in dieser oder ¨ahnlicher Form noch bei keiner anderen Institution eingereicht. Ich habe bisher keine erfolglosen Promotionsversuche un- ternommen. D¨usseldorf,den . ... ... ... (Aaron Weimann) Statement of authorship I hereby certify that this dissertation is the result of my own work. No other person's work has been used without due acknowledgement. This dissertation has not been submitted in the same or similar form to other institutions. I have not previously failed a doctoral examination procedure. Summary Bacteria live in almost any imaginable environment, from the most extreme envi- ronments (e.g. in hydrothermal vents) to the bovine and human gastrointestinal tract. By adapting to such diverse environments, they have developed a large arsenal of enzymes involved in a wide variety of biochemical reactions. While some such enzymes support our digestion or can be used for the optimization of biotechnological processes, others may be harmful { e.g. mediating the roles of bacteria in human diseases. -

The Influence of Sodium Chloride on the Performance of Gammarus Amphipods and the Community Composition of Microbes Associated with Leaf Detritus

THE INFLUENCE OF SODIUM CHLORIDE ON THE PERFORMANCE OF GAMMARUS AMPHIPODS AND THE COMMUNITY COMPOSITION OF MICROBES ASSOCIATED WITH LEAF DETRITUS By Shelby McIlheran Leaf litter decomposition is a fundamental part of the carbon cycle and helps support aquatic food webs along with being an important assessment of the health of rivers and streams. Disruptions in this organic matter breakdown can signal problems in other parts of ecosystems. One disruption is rising chloride concentrations. Chloride concentrations are increasing in many rivers worldwide due to anthropogenic sources that can harm biota and affect ecosystem processes. Elevated chloride concentrations can lead to lethal or sublethal impacts. While many studies have shown that excessive chloride uptake impacts health (e.g. lowered respiration and growth rates) in a wide variety of aquatic organisms including microbes and benthic invertebrates). The impacts of high chloride concentrations on decomposers are less well understood. My research objective was to assess how increasing chloride concentrations affect the performance and diversity of decomposer organisms in freshwater systems. I experimentally manipulated chloride concentrations in microcosms containing leaves colonized by microbes or containing leaves, microbes and amphipods. Respiration rate, decomposition, and community composition of the microbes were measured along with the amphipod growth rate, egestion rate, and mortality. Elevated chloride concentration did not impact microbial respiration rates or leaf decomposition, but had large impacts on bacteria community composition. It did cause a decrease in instantaneous growth rate, and 100% mortality in the highest amphipod chloride treatment, but amphipod egestion rate was not significantly affected. The results of my research suggest that the widespread increases in chloride concentrations in rivers will have an impact on decomposer communities in these systems. -

UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations

UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations Identification of Anaerobic Cocci Issued by the Standards Unit, Microbiology Services, PHE Bacteriology – Identification | ID 14 | Issue no: 3 | Issue date: 04.02.15 | Page: 1 of 29 © Crown copyright 2015 Identification of Anaerobic Cocci Acknowledgments UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations (SMIs) are developed under the auspices of Public Health England (PHE) working in partnership with the National Health Service (NHS), Public Health Wales and with the professional organisations whose logos are displayed below and listed on the website https://www.gov.uk/uk- standards-for-microbiology-investigations-smi-quality-and-consistency-in-clinical- laboratories. SMIs are developed, reviewed and revised by various working groups which are overseen by a steering committee (see https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/standards-for-microbiology-investigations- steering-committee). The contributions of many individuals in clinical, specialist and reference laboratories who have provided information and comments during the development of this document are acknowledged. We are grateful to the Medical Editors for editing the medical content. For further information please contact us at: Standards Unit Microbiology Services Public Health England 61 Colindale Avenue London NW9 5EQ E-mail: [email protected] Website: https://www.gov.uk/uk-standards-for-microbiology-investigations-smi-quality- and-consistency-in-clinical-laboratories UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations are produced in association with: Logos correct at time of publishing. Bacteriology – Identification | ID 14 | Issue no: 3 | Issue date: 04.02.15 | Page: 2 of 29 UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations | Issued by the Standards Unit, Public Health England Identification of Anaerobic Cocci Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ......................................................................................................... -

Compile.Xlsx

Silva OTU GS1A % PS1B % Taxonomy_Silva_132 otu0001 0 0 2 0.05 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Acidobacteria_un;Acidobacteria_un;Acidobacteria_un;Acidobacteria_un; otu0002 0 0 1 0.02 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Acidobacteriia;Solibacterales;Solibacteraceae_(Subgroup_3);PAUC26f; otu0003 49 0.82 5 0.12 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Aminicenantia;Aminicenantales;Aminicenantales_fa;Aminicenantales_ge; otu0004 1 0.02 7 0.17 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;AT-s3-28;AT-s3-28_or;AT-s3-28_fa;AT-s3-28_ge; otu0005 1 0.02 0 0 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Blastocatellia_(Subgroup_4);Blastocatellales;Blastocatellaceae;Blastocatella; otu0006 0 0 2 0.05 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Holophagae;Subgroup_7;Subgroup_7_fa;Subgroup_7_ge; otu0007 1 0.02 0 0 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;ODP1230B23.02;ODP1230B23.02_or;ODP1230B23.02_fa;ODP1230B23.02_ge; otu0008 1 0.02 15 0.36 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Subgroup_17;Subgroup_17_or;Subgroup_17_fa;Subgroup_17_ge; otu0009 9 0.15 41 0.99 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Subgroup_21;Subgroup_21_or;Subgroup_21_fa;Subgroup_21_ge; otu0010 5 0.08 50 1.21 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Subgroup_22;Subgroup_22_or;Subgroup_22_fa;Subgroup_22_ge; otu0011 2 0.03 11 0.27 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Subgroup_26;Subgroup_26_or;Subgroup_26_fa;Subgroup_26_ge; otu0012 0 0 1 0.02 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Subgroup_5;Subgroup_5_or;Subgroup_5_fa;Subgroup_5_ge; otu0013 1 0.02 13 0.32 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Subgroup_6;Subgroup_6_or;Subgroup_6_fa;Subgroup_6_ge; otu0014 0 0 1 0.02 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Subgroup_6;Subgroup_6_un;Subgroup_6_un;Subgroup_6_un; otu0015 8 0.13 30 0.73 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Subgroup_9;Subgroup_9_or;Subgroup_9_fa;Subgroup_9_ge; -

A Review on the Biotechnological Applications of the Operational Group Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens

microorganisms Review A Review on the Biotechnological Applications of the Operational Group Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Mohamad Syazwan Ngalimat 1 , Radin Shafierul Radin Yahaya 1, Mohamad Malik Al-adil Baharudin 1, Syafiqah Mohd. Yaminudin 2, Murni Karim 2,3 , Siti Aqlima Ahmad 4 and Suriana Sabri 1,5,* 1 Enzyme and Microbial Technology Research Center, Faculty of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang 43400, Selangor, Malaysia; [email protected] (M.S.N.); radinshafi[email protected] (R.S.R.Y.); [email protected] (M.M.A.-a.B.) 2 Department of Aquaculture, Faculty of Agriculture, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang 43400, Selangor, Malaysia; [email protected] (S.M.Y.); [email protected] (M.K.) 3 Laboratory of Sustainable Aquaculture, International Institute of Aquaculture and Aquatic Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Port Dickson 71050, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia 4 Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang 43400, Selangor, Malaysia; [email protected] 5 Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang 43400, Selangor, Malaysia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +603-97698298 Abstract: Bacteria under the operational group Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (OGBa) are all Gram-positive, endospore-forming, and rod-shaped. Taxonomically, the OGBa belongs to the Bacillus subtilis species complex, family Bacillaceae, class Bacilli, and phylum Firmicutes. To date, the OGBa comprises four bacterial species: Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Bacillus siamensis, Bacillus velezensis and Bacillus Citation: Ngalimat, M.S.; Yahaya, nakamurai. They are widely distributed in various niches including soil, plants, food, and water. A R.S.R.; Baharudin, M.M.A.-a.; resurgence in genome mining has caused an increased focus on the biotechnological applications Yaminudin, S.M..; Karim, M.; Ahmad, of bacterial species belonging to the OGBa.