This Is an Author-Produced PDF of an Book Chapter Accepted For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Be Prepared: Communism and the Politics of Scouting in 1950S Britain

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository This item was submitted to Loughborough’s Institutional Repository (https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/) by the author and is made available under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ Be Prepared: Communism and the Politics of Scouting in 1950s Britain Sarah Mills To cite this paper: Mills, S. (2011) Be Prepared: Communism and the Politics of Scouting in 1950s Britain, Contemporary British History 25 (3): 429-450 This article examines the exposure, and in some cases dismissal, of Boy Scouts who belonged or sympathised with the Young Communist League in Britain during the early 1950s. A focus on the rationale and repercussions of the organisation’s approach and attitudes towards ‘Red Scouts’ found within their ‘ranks’ extends our understanding of youth movements and their often complex and conflicting ideological foundations. In particular, the post World War Two period presented significant challenges to these spaces of youth work in terms of broader social and political change in Britain. An analysis of the politics of scouting in relation to Red Scouts questions not only the assertion that British McCarthyism was ‘silent’, but also brings young people firmly into focus as part of a more everyday politics of Communism in British society. Key Words: Communism, British McCarthyism, Cultural Cold War, Boy Scouts, Youth Movements INTRODUCTION The imperial sensibilities and gender-based politics of the Scout movement in Britain have been well studied by historians. -

Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe Published on Iitaly.Org (

Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe Natasha Lardera (February 21, 2014) On view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, until September 1st, 2014, this thorough exploration of the Futurist movement, a major modernist expression that in many ways remains little known among American audiences, promises to show audiences a little known branch of Italian art. Giovanni Acquaviva, Guillaume Apollinaire, Fedele Azari, Francesco Balilla Pratella, Giacomo Balla, Barbara (Olga Biglieri), Benedetta (Benedetta Cappa Marinetti), Mario Bellusi, Ottavio Berard, Romeo Bevilacqua, Piero Boccardi, Umberto Boccioni, Enrico Bona, Aroldo Bonzagni, Anton Giulio Bragaglia, Arturo Bragaglia, Alessandro Bruschetti, Paolo Buzzi, Mauro Camuzzi, Francesco Cangiullo, Pasqualino Cangiullo, Mario Carli, Carlo Carra, Mario Castagneri, Giannina Censi, Cesare Cerati, Mario Chiattone, Gilbert Clavel, Bruno Corra (Bruno Ginanni Corradini), Tullio Crali, Tullio d’Albisola (Tullio Mazzotti), Ferruccio Demanins, Fortunato Depero, Nicolaj Diulgheroff, Gerardo Dottori, Fillia (Luigi Page 1 of 3 Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) Colombo), Luciano Folgore (Omero Vecchi), Corrado Govoni, Virgilio Marchi, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Alberto Martini, Pino Masnata, Filippo Masoero, Angiolo Mazzoni, Torido Mazzotti, Alberto Montacchini, Nelson Morpurgo, Bruno Munari, N. Nicciani, Vinicio Paladini -

El Universo Futurista. 1909 - 1936

Press kit El Universo Futurista. Departamento de Prensa [+54-11] 4104 1044 1909 - 1936 [email protected] www.proa.org Colección MART - Fundación PROA Av. Pedro de Mendoza 1929 [C1169AAD] Buenos Aires Argentina Desde el 30 de marzo hasta el 4 de julio de 2010 PROA Giannetto Malmerendi. S i g n o r i n a + a m b i e n t e , 1914. Oleo sobre tela, 59 x 48 cm. MART, Rovereto …futurista, o sea, falto de pasado y libre de tradiciones ManifiestoLa Cinematografía Futurista. 1916 El Universo Futurista. 1909 - 1936 Inauguración Martes 30 de marzo de 2010, 19 horas - Con el apoyo del Instituto Italiano de Cultura de Buenos Aires - Embajada de Italia en Argentina Con el auspicio permanente de Tenaris / Organización Techint Idea y proyecto Departamento de Prensa MART Juan Pablo Correa / Andrés Herrera / Laura Jaul Fundación PROA [+54 11] 4104 1044 [email protected] Curadora www.proa.org Gabriella Belli Concepto y desarrollo de textos Comité asesor Franco Torchia Cecilia Iida Cintia Mezza Cecilia Rabossi Producción Beatrice Avanzi Clarenza Catullo Camila Jurado Aimé Iglesias Lukin Diseño expositivo Caruso-Torricella, Milán Conservación Teresa Pereda Diseño gráfico Spin, Londres Fundación PROA Av. Pedro de Mendoza 1929 La Boca, Ciudad de Buenos Aires - Horario Martes a domingo de 11 a 19 hs Lunes cerrado – - El Universo Futurista pág 3 1909-1936 …futurista, o sea, falto de pasado y libre de tradiciones ManifiestoLa Cinematografía Futurista. 1916 El Universo Futurista. 1909 - 1936 Colección MART - Museo di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, Italia Curadora: Gabriella Belli Futurismo no es futuro. -

This Is an Author-Produced PDF of an Article Published in the Conversation, May 2016

1 This is an author-produced PDF of an article published in The Conversation, May 2016. The fully formatted and illustrated publication can be accessed at https://theconversation.com/rebel-youth-how-britains-woodcraft-folk-tried-to-change-the- world-55892 Rebel youth: how Britain’s woodcraft folk tried to change the world Annebella Pollen Children with Kibbo Kift leader, John Hargrave, 1928. Courtesy of Tim Turner Are the young people you know more likely to identify a Dalek or a magpie? The National Trust asserts that Daleks come up trumps, complaining that “nature is being exterminated from children’s lives”. Concerns about young people’s increasingly sedentary lifestyles and lack of exposure to nature have led to a number of popular outdoor endeavours including schemes to “rewild the child”. This may seem to be a particularly 21st-century issue, but the urge to counteract the influence of the city on the lives of young people has a long history. 2 Precisely 100 years ago, in the midst of World War I, a family of Quakers in Cambridge set up a youth organisation designed to offer outdoor coeducational experiences without the militarism and imperialism that they perceived in the Boy Scouts. They called the group the Order of Woodcraft Chivalry. This marked the start of a larger movement, spread across a range of organisations emerging during and after the war years. Founded on pacifist ideals and informed by a mystical understanding of the natural world, British youth groups based on what were described as “woodcraft” principles sought radical alternatives to so-called civilisation through camping and ceremony, hiking and handicraft. -

Ernest Thompson Seton 1860-1946

Ernest Thompson Seton 1860-1946 Ernest Thompson Seton was born in South Shields, Durham, England but emigrated to Toronto, Ontario with his family at the age of 6. His original name was Ernest Seton Thompson. He was the son of a ship builder who, having lost a significant amount of money left for Canada to try farming. Unsuccessful at that too, his father gained employment as an accountant. Macleod records that much of Ernest Thompson Seton 's imaginative life between the ages of ten and fifteen was centered in the wooded ravines at the edge of town, 'where he built a little cabin and spent long hours in nature study and Indian fantasy'. His father was overbearing and emotionally distant - and he tried to guide Seton away from his love of nature into more conventional career paths. He displayed a considerable talent for painting and illustration and gained a scholarship for the Royal Academy of Art in London. However, he was unable to complete the scholarship (in part through bad health). His daughter records that his first visit to the United States was in December 1883. Ernest Thompson Seton went to New York where met with many naturalists, ornithologists and writers. From then until the late 1880's he split his time between Carberry, Toronto and New York - becoming an established wildlife artist (Seton-Barber undated). In 1902 he wrote the first of a series of articles that began the Woodcraft movement (published in the Ladies Home Journal). The first article appeared in May, 1902. On the first day of July in 1902, he founded the Woodcraft Indians, when he invited a group of boys to camp at his estate in Connecticut and experimented with woodcraft and Indian-style camping. -

El Universo Futurista

Press kit D e p a r ta m e n t o d e P r e n s a [+5 4 -11] 410 4 10 4 4 [email protected] w w w.proa.org - F u n d a ció n P R OA Av. Pe d r o d e M e n do z a 1929 [C1169 A A D] B u e n o s A i r e s Argentina El Universo Futurista: 1909 - 1936 PROA / Juanita Inauguración El Universo Futurista Sánchez / Guadalupe Titoy / Sábado 23 de enero de 2010, 18 horas Ana Van Tuyll / Camila Villarruel Exposición Fundación Proa Dirección general Socios fundadores Adriana Rosenberg Zulema Fernández / Paolo Rocca / Adriana Rosenberg Curaduría Consejo directivo Gabriella Belli Presidente Idea y proyecto Adriana Rosenberg Museo d’Arte Moderna e Vicepresidente Contemporanea di Trento Amilcar Romeo e Rovereto Secretario Fundación Proa Horacio de las Carreras Tesorero Comité asesor Héctor Magariños Cecilia Iida Vocal Cintia Mezza Juan José Cambre Cecilia Rabossi Consejo de administración Producción Proyectos especiales Fortunato Depero Beatrice Avanzi Guillermo Goldschmidt Mandrie di auto, 1930 Clarenza Catullo Gerencia (Manada de autos). Camila Jurado Victoria Dotti Fotocollage, 31 x 19 cm MART, Rovereto Departamento programación Diseño expositivo Aimé Iglesias Lukin / Camila Jurado Caruso-Torricella, Milán-París Administración Mirta Varela / Mariangeles Garavano Iluminación / Javier Varela Fundación Proa Diseño María Karina Kevorkian / Jorge Diseño gráfico Lewis D e p a r t a m e n t o d e P r e n s a Spin Educación A n d r é s H e r r e r a / L a u r a J a u l Fundación Proa Paulina Guarnieri / Margarita Rocha [email protected] Prensa [+ 5 4 1 1] 4 1 0 4 - 1 0 4 4 Montaje Juan Pablo Correa / Andrés Herrera / - Sergio Avello / Gisela Korth / Laura Jaul / Franco Torchia F u n d a c i ó n P R O A Pablo Zaefferer A v. -

THE OTHER SCHOOL Annebella Pollen

This a pre-copy edited version of a 2017 article submitted to the website Alma. The final version appeared in a Spanish language translation as l’Altra Escola https://miradesambanima.org/miradas/laltra-escola/ This 800-word article was a commercial commission by L’Obra Social, an educational project supported by the cultural foundation of the Spanish bank, La Caixa. The article explores histories of outdoor education in the light of current anxieties about children’s lack of contact with nature. It draws on Pollen’s research into the early twentieth century woodcraft movement in order to provide critical context for new educational practices that teach children outdoor skills. THE OTHER SCHOOL Annebella Pollen There’s a powerful current anxiety that urban children are losing touch with nature. The generation so very well connected to the internet and social media are seen to be ever more disconnected from the benefits of the great outdoors. Whether these anxieties cluster around sedentary lifestyles and child obesity, or the loss of knowledge in a world where many urban children find it easier to identify corporate logos than names of plants and animals, many parents and educators have expressed concern that contemporary childhood needs an injection of fresh air and green space. As a consequence, a wide range of recent endeavours have been put in place to promote outdoor opportunities for young people. These include popular cross- European educational programmes such as Forest School, which encourages children to adopt activities that use nature as a classroom, and to develop “bushcraft” skills, including making fires and woodland crafts. -

A History of Youth Work

youthwork.book Page 3 Wednesday, May 7, 2008 2:43 PM A century of youth work policy youthwork.book Page 4 Wednesday, May 7, 2008 2:43 PM youthwork.book Page 5 Wednesday, May 7, 2008 2:43 PM A century of youth work policy Filip COUSSÉE youthwork.book Page 6 Wednesday, May 7, 2008 2:43 PM © Academia Press Eekhout 2 9000 Gent Tel. 09/233 80 88 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.academiapress.be J. Story-Scientia bvba Wetenschappelijke Boekhandel Sint-Kwintensberg 87 B-9000 Gent Tel. 09/225 57 57 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.story.be Filip Coussée A century of youth work policy Gent, Academia Press, 2008, ### pp. Opmaak: proxess.be ISBN 978 90 382 #### # D/2008/4804/### NUR ### U #### Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd en/of vermenigvuldigd door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze dan ook, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. youthwork.book Page 1 Wednesday, May 7, 2008 2:43 PM Table of Contents Chapter 1. The youth work paradox . 3 1.1. The identity crisis of youth work. 3 1.2. An international perspective . 8 1.3. A historical perspective. 13 1.4. An empirical perspective . 15 Chapter 2. That is youth work! . 17 2.1. New paths to social integration . 17 2.2. Emancipation of young people . 23 2.3. The youth movement becomes a youth work method. 28 2.4. Youth Movement incorporated by the Catholic Action. 37 2.5. From differentiated to inaccessible youth work . -

1. Identify the Poet Usually Referred to As “The Poet’S Writers of the 18Th Century

1 | P a g e LITERATURE: A MODERN OUTLOOK 13. Pope’s The Dunciad satirises Literary tastes. 14. ‘Blue Stocking’ is a term associated with Women 1. Identify the poet usually referred to as “the poet’s writers of the 18th century. poet”- Edmund Spenser (called by Lamb) 15. Who proposed to popularize and bring philosophy 2. The college known as “Solomon’s House’ figures in to the coffee-houses in the 18th century? Addison Bacon’s The New Atlantis (Ben Salem) 16. Brobdingnag is the land of Men of towering height 3. Religio Medici was written by Sir Thomas Browne (Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels). 4. “The mind is its own place, and in itself 17. Who claimed to write fiction that could be called Can make a Heaven of Hell, a Hell of Heaven” ‘comic epic in prose’? Henry Fielding ‘Joseph The above lines occur in Milton’s Paradise Lost Andrews’. (Book I) 18. Who is the author of the following lines? 5. “Let me not to the marriage of true minds “To me the meanest flower that blows can give Admit impediments: Love is not love Thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears” – Which alters when it alteration finds” Wordsworth (Intimations of immortality) The above lines are culled from a Sonnet by 19. In Biographia Literaria Coleridge differed with Shakespeare (Sonnet 116) Wordsworth mainly in his views on Language in 6. Who wrote the poem ‘To His Coy Mistress’? Poetry. Andrew Marvell 20. Shelley intended his poetry to provide 7. Who is the author of the poem ‘Hero and Leander’? Revolutionary Message. -

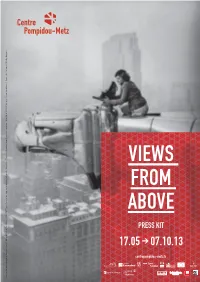

Views from Above Press Kit 17.05 > 07.10.13

, New York, 1935. Photo by Oscar Graubner / Time Life Pictures / Getty Images VIEWS FROM ABOVE PRESS KIT 17.05 > 07.10.13 centrepompidou-metz.fr American photographer and journalist Margaret Bourke-White (1904-1971) perches on an eagle head gargoyle at the top of the Chrysler Building and focuses a camera BAT_DP_COVER_v1.indd 3-4 09/05/12 11:56 VIEWS FROM ABOVE CONTENTS 1. GENERAL PRESENTATION ............................................................................................................ 02 2. STRUCTURE OF THE EXHIBITION ............................................................................................. 03 GRANDE NEF UPHEAVAL – PLANIMETRY – EXTENSION – ALIENATION – DOMINATION .................................................................................. 04 GALERIE 1 TOPOGRAPHY – URBANISATION – SUPERVISION ........................................................................................................................................ 06 FOCUS ON "ÉCHO D'ÉCHOS: FROM ABOVE, WORK IN SITU, 2011", BY DANIEL BUREN ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 08 3. LIST OF EXHIBITED ARTISTS ...................................................................................................... 09 4. LENDERS ................................................................................................................................................... 10 5. CATALOGUE .............................................................................................................................................. -

The Boy Scouts, Class and Militarism in Relation to British Youth Movements 1908-1930*

/. 0. SPRINGHALL THE BOY SCOUTS, CLASS AND MILITARISM IN RELATION TO BRITISH YOUTH MOVEMENTS 1908-1930* In the 1960's academic attention became increasingly focused, in many cases of necessity, on the forms taken by student protest and, possibly in conjunction with this, there appeared almost simultaneously a corresponding upsurge of interest in the history of organized inter- national youth movements, many of them with their origins in the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries.1 Such a development in historiography would seem to contradict the statement once made by an English youth leader, Leslie Paul, that "because the apologetics of youth movements are callow, their arguments crude, and their prac- tices puerile, they are dismissed or ignored by scholars."2 It is certainly refreshing to see discussion of the Boy Scout movement rise above easy humour at the expense of Baden-Powell's more ec- centric views on adolescent sex education.3 Yet despite the change in historical perspective, very little has been done until comparatively recently to place Scouting, as this article cautiously attempts to do, * I would like to thank my colleagues - past and present - at the Lanchester Polytechnic, Coventry, and the New University of Ulster who commented on and made suggestions with regards to earlier drafts of this article. The faults and omissions are, of course, all my own. 1 Cf. A series of essays on "Generations in Conflict" published in: The Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 4, No 2 (1969), and Vol. 5, No 1 (1970); Walter Z. Laqueur, Young Germany: A history of the German Youth Movement (London, 1962); Robert Hervet, Les Compagnons de France (Paris, 1965); Radomir Luza, History of the International Socialist Youth Movement (Leiden, 1970). -

In Wodue Ti on a GREEN LAND FAR AWAY: a LOOK AT

A GREEN LAND FAR AWAY: A LOOK AT ~E ORIGI NS OF THE GREEN Mo/EMENT In wodue ti on In a previous paper on German self-identity and attitudes to Nature (JASO, Vol. XVI, no.l, pp. 1-18) I argued that one of its main strains was a dissatisfaction with the shifting political and territorial boundaries of the nation and a search for a more authentic, earth-bound identity. This search led to a politically radical 'ecologism' which pre-dated National Socialism, but which emerged as an underlying theme in the Third Reich, reappearing in Germany well after the Second World War in more obviously left oriented groups. In this paper I want to examine the origins and growth of the Green movement itself in England and Germany. While the insecur ity of national identity in Germany was not exactly paralleled in England, the English experience nonetheless demonstrates a search for lost 'roots' after 1880. This crisis of identity fused with criticisms of orthodox liberal economists and mechanistic biolog ists to produce the ecologists and, later, the Greens. This is a shortened version of a paper first given to my own semi nar on Modern Conservatism at Trinity College, Oxford, in June 1985; it was subsequently delivered at a Social Anthropology semi nar chaired by Edwin Ardener at St John's College, Oxford, on 28 October 1985, and at the seminar on Political Theory organised by John Gray and Bill Weinstein at Balliol College, Oxford, on 1 November 1985. Notes have been kept to the minimum necessary to identify actual quotations and the mare obscure works I have cited.