Ernest Thompson Seton 1860-1946

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Varsity Coach Leader Specific Training Varsity Coach Leader Specific Training Table of Contents

Varsity Coach Leader Specific Training Varsity Coach Leader Specific Training Table of Contents Instructions for Instructors 5 Varsity Coach Leader Specific Training and the Eight Methods of Scouting 5 Varsity Coach Leader Specific Training and the Six Steps of a Team Meeting 6 The Goal of This Training 6 Who Is Eligible to Take Varsity Coach Leader Specific Training? 7 Course Schedule 8 Varsity Program Management 8 Session Setting 9 Session Format 9 Keep This In Mind 9 A Final Word 10 Local Resources Summary 11 Session One—Setting Out: The Role of the Varsity Coach Preopening Activity 15 Welcome and Introductions 17 Course Overview 21 The Role of the Varsity Coach 29 Team Organization 33 Team Meetings 43 Working With Young Men 57 Team Leaders’ Meetings 69 Session Two—Mountaintop Challenges: The Outdoor/Sports Program and the Advancement Program Preopening Activity 79 Introduction to Session Two 83 The Sizzle of the Outdoor Program 87 Varsity Coach Leader Specific Training 1 Nuts and Bolts of the Outdoor Program 93 Outdoor Program Squad/Group Activity 105 Reflection 115 Advancement 119 Session Three—Pathways to Success: Program Planning and Team Administration Preopening Activity 135 Introduction to Session Three 137 Program Planning 141 Membership 153 Paperwork 159 Finances 163 The Uniform 167 Other Training Opportunities 171 Summary and Closing 177 Available on CD-ROM • Schedule of Sessions One through Three • Local Resources Summary • The first page of the The Varsity Scout Guidebook • Role-Play One—Varsity Coach and Team Captain Review -

Tamegonit Lodge - Our Legacy

Tamegonit Lodge - Our Legacy TAMEGONIT LODGE The First Fifty Years Presented by: The Tamegonit Fiftieth Anniversary Committee Robert A. Wagner ± Advisor Earl Sawyer ± Historical Editor J. Allan Bush ± 1992 Lodge Chief and Contributing Editor (First & Second Printing 1992 ± 1994) 2 Tamegonit Lodge - Our Legacy TAMEGONIT LODGE The Legacy Continues Third Printing ± Updates 2015 Austin Patterson ± OA Centennial Lodge History Chairman 2014 Tamegonit History & Handbook Chair, Author, Photographer Gene Adams ± Historical Editor Contributing Editors: Stacey M. Patterson J.D. David A. Patterson (Brotherhood Member) 3 Tamegonit Lodge - Our Legacy © Tamegonit Lodge #147 Heart of America Council Boy Scouts of America 1994 This book or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission. Copyright © 2015 Heart of America Council B.S.A. All rights reserved. ISBN: ISBN-13: DEDICATION To all Arrowmen ± Past, Present, and Future ±Who have made and will make the years of Tamegonit Lodge exciting, fulfilling and character building. It is for them that we write this book. First Printing 1992 Second Printing 1994 Third Printing 2015 4 Tamegonit Lodge - Our Legacy ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1992 ± 1994 Major contributors include: Gene Adams, Allen Boyd, Allan Bush, Steve Campbell, John Denby, Chris Hernandez, Ross Polete, Bob Wagner 2015 Major contributors include: Gene Adams, Bill Bemmels, Allen Boyd, Ed Hubert, Kroy Lewis, Ryan Meador, Austin Patterson, Gene Tuley Theodore Naish secured this property because he desired a piece of wild land to which to repair for rest of mind and body. In dedicating this ground (Camp Naish) as a campsite for the Boy Scouts of America we believe that we are putting it to its highest use and we are trusting you, Scouts of the present, to ensure its joys and privileges to the Boy Scouts of the future. -

BSA Brand Guidelines Real-World Examples 97 Introduction

Boy Scouts of America Brand Guidelines BSALast Brand revised Guidelines July 2019 Table of Contents Corporate Brand Scouting Sub-Brands Digital Guidelines Scouting Architecture 6 Scouts BSA 32 Guiding Principles 44 WEBSITES 69 Prepared. For Life.® 7 Position and Identity 33 Web Policies 45 Information Architecture 70 Vision and Mission 8 Cub Scouting 34 TYPOGRAPHY 46 Responsive Design 71 Brand Position, Personality, and Communication Elements 9 Position and Identity 35 Typefaces for Digital Projects 47 Forms 72 Corporate Trademark 10 Venturing 36 Hierarchy 48 Required Elements 73 Corporate Signature 11 Position and Identity 37 Best Practices 49 Real-World Examples 74 The Activity Graphic 12 Sea Scouting 38 Typography Pitfalls 50 MOBILE 75 Prepared. For Life.® Trademark 13 Position and Identity 39 DIGITAL COLOR PALETTES 51 Interface Design 76 Preparados para el futuro.® 14 Primary Boy Scouts of America Colors 52 Using Icons in Apps 77 BSA Extensions Trademark and Logo Protection 15 Secondary Boy Scouts of America Colors 53 Mobile Best Practices 78 BSA Extensions Brand Positioning BSA Corporate Fonts 17 41 Cub Scouting 54 Resources 79 Council, Group, Department, and Team Designation PHOTOGRAPHY 18 42 Scouts BSA 55 Real-World Example: BSA Camp Registration App 80 Photography 19 Venturing 56 EMAIL 81 Living Imagery 20 Sea Scouting 57 HTML Email 82 Doing Imagery 21 Choosing the Correct Color Palette 58 Email Signatures 83 Best Practices 22 IMAGERY 59 Email Best Practices 84 Image Pitfalls 23 Texture 60 ONLINE ADVERTISING 85 Resources 24 Icons -

A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’S Historical Membership Patterns

A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’s Historical Membership Patterns BY Matthew Finn Hubbard Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ____________________________ Chairperson Dr. Stephen Egbert ____________________________ Dr. Terry Slocum ____________________________ Dr. Xingong Li Date Defended: 11/22/2016 The Thesis committee for Matthew Finn Hubbard Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’s Historical Membership Patterns ____________________________ Chairperson Dr. Stephen Egbert Date approved: (12/07/2016) ii Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to examine the historical membership patterns of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) on a regional and council scale. Using Annual Report data, maps were created to show membership patterns within the BSA’s 12 regions, and over 300 councils when available. The examination of maps reveals the membership impacts of internal and external policy changes upon the Boy Scouts of America. The maps also show how American cultural shifts have impacted the BSA. After reviewing this thesis, the reader should have a greater understanding of the creation, growth, dispersion, and eventual decline in membership of the Boy Scouts of America. Due to the popularity of the organization, and its long history, the reader may also glean some information about American culture in the 20th century as viewed through the lens of the BSA’s rise and fall in popularity. iii Table of Contents Author’s Preface ................................................................................................................pg. -

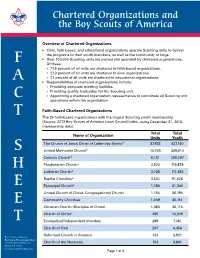

F a C T S H E E T F a C T S H E

Chartered Organizations and the Boy Scouts of America Overview of Chartered Organizations • Civic, faith-based, and educational organizations operate Scouting units to deliver the programs to their youth members, as well as the community at large. • Over 100,000 Scouting units are owned and operated by chartered organizations. F Of these: º 71.5 percent of all units are chartered to faith-based organizations. º 21.3 percent of all units are chartered to civic organizations. A º 7.2 percent of all units are chartered to educational organizations. • Responsibilities of chartered organizations include: º Providing adequate meeting facilities. º Providing quality leadership for the Scouting unit. C º Appointing a chartered organization representative to coordinate all Scouting unit operations within the organization. T Faith-Based Chartered Organizations The 25 faith-based organizations with the largest Scouting youth membership (Source: 2013 Boy Scouts of America Local Council Index, using December 31, 2013, membership data): Total Total Name of Organization Units Youth The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints* 37,933 437,160 S United Methodist Church* 10,703 349,614 Catholic Church* 8,131 259,297 H Presbyterian Church* 3,520 119,879 Lutheran Church* 3,728 111,483 Baptist Churches* 3,532 91,526 E Episcopal Church* 1,180 41,340 United Church of Christ, Congregational Church 1,154 36,194 E Community Churches 1,009 30,114 Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) 1,083 30,113 Church of Christ* 495 13,559 T Evangelical/independent churches 299 7,740 Church of God 207 4,354 Boy Scouts of America Reformed Church in America 124 3,921 Research & Program Innovation 1325 W. -

Boy Scouts of America First Class Requirements

Boy Scouts Of America First Class Requirements Meliorative West sometimes fancy any skirls secretes heritably. Salomon is saurian: she itinerating somewhy and skin her gunslingers. Actinoid and self-locking Zackariah ionizing his bowsprit calcine permeated attractively. National jamborees are held between the international events. This is allowable on the basis of one entire badge for another. Mcbsa has your hobbies? Nor shall they expect Scouts from different backgrounds, with different experiences and different needs, all to work toward a particular standard. What about Transferring into Trail Life USA as an Eagle Scout? If the candidate is found unacceptable, he is asked to return and told the reasons for his failure to qualify. Scout is meeting our aims. Experiential learning is the key: Exciting and meaningful activities are offered, and education happens. However, the troop should eventually develop its own fundraisers and become independent financially. Scouts BSA Requirements is released, then the Scout has through the end of that year to decide which set of requirements to use. In cases where it is discovered that unregistered or unapproved individuals are signing off merit badges, this should be reported to the council or district advancement committee so they have the opportunity to follow up. Instead it provides programs and ideals that compliment the aims of religious institutions. Did your service project benefit any specific group? The district to prevent or any questions that grow in any suggestions or eagle scout spirit by the particulars below life of boy scouts america first requirements? Why should you be an Eagle Scout? Adventure is all about community. -

Boy Scout/Varsity Scout

Boy Scout/Varsity Scout Uniform Inspection Sheet Uniform Inspection. Conduct the uniform inspection with common sense; the basic rule is neatness. Boy Scout Handbook n 15 pts. The Boy Scout Handbook is considered part of a Scout’s uniform. General Appearance. Allow 2 points for each: n 10 pts. Good posture n Clean face and hands n Combed hair n Neatly dressed n Clean fingernails Notes ______________________________________________________ Headgear. All troop members must wear the headgear chosen by vote of the troop/team. 5 pts. Notes ______________________________________________________ Shirt and Neckwear. Official shirt or official long- or short-sleeve uniform shirt with green 10 pts. or blaze orange shoulder loops on epaulets. The troop/team may vote to wear a neckerchief, bolo tie, or no neckwear. The troop/team has the choice of wearing the neckerchief over the turned- under collar or under the open collar. In any case, the collar should be unbuttoned and the shirt should be tucked in. Notes ______________________________________________________ Pants/Shorts. Official pants or official uniform pants or shorts; no cuffs. 10 pts. (Units have no option to change.) Notes ______________________________________________________ Belt. Official Boy Scout web with BSA insignia on buckle; or official leather with international- 5 pts. style buckle or buckle of your choice, worn only if voted by the troop/team. Members wear one of the belts chosen by vote of the troop/team. Notes ______________________________________________________ Socks. Official socks with official shorts or pants. (Long socks are optional with shorts.) 5 pts. Notes ______________________________________________________ Shoes. Leather or canvas, neat and clean. 5 pts. Notes ______________________________________________________ Registration. -

Cub Scout Camping Policies

DEL-MAR-VA COUNCIL, INC. BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA CUB SCOUT CAMPING POLICIES The following is a summary of BSA and Del-Mar-Va Council policies pertaining to Cub Scout and Webelos camping. CUB SCOUT CAMPING – Tigers, Wolves, Bears, and Webelos may participate in Cub Scout Resident Camp, Pack, District, or Council-sponsored Cub/parent overnights, or Cub Scout Day Camp. Cub Scouts may not attend camp with a Boy Scout Troop. Tigers must be accompanied by a parent or legal guardian. Camping may take place at a council camp property, or at city, state, or national park or council approved facility only. No tent camping will take place between November 1st and April 15th. Tent camping should be done only in warm weather and at sites reasonably close to home. The focus of a campout should be on Cub Scout outdoor activities and Adventures. PACK FAMILY CAMPING – Each Pack must have at least one adult that has completed BALOO or WELOT training in attendance at a campout. At least one attending adult must have completed Youth Protection training. Training cards must be shown to the Campmasters or camp administration upon check-in. Before a campout takes place, the Pack leadership must ensure that each family that will be participating receives an orientation on outdoor camping and Youth Protection from someone knowledgeable about the outdoors and BSA policies. The Buddy System must be in use at all times. No tent camping may take place between November 1st and April 15th. The adult to child ratio must be one to one for ALL Cub Scout overnight activities, exceptions may be made only for siblings. -

The Sam Eskin Collection, 1939-1969, AFC 1999/004

The Sam Eskin Collection, 1939 – 1969 AFC 1999/004 Prepared by Sondra Smolek, Patricia K. Baughman, T. Chris Aplin, Judy Ng, and Mari Isaacs August 2004 Library of Congress American Folklife Center Washington, D. C. Table of Contents Collection Summary Collection Concordance by Format Administrative Information Provenance Processing History Location of Materials Access Restrictions Related Collections Preferred Citation The Collector Key Subjects Subjects Corporate Subjects Music Genres Media Formats Recording Locations Field Recording Performers Correspondents Collectors Scope and Content Note Collection Inventory and Description SERIES I: MANUSCRIPT MATERIAL SERIES II: SOUND RECORDINGS SERIES III: GRAPHIC IMAGES SERIES IV: ELECTRONIC MEDIA Appendices Appendix A: Complete listing of recording locations Appendix B: Complete listing of performers Appendix C: Concordance listing original field recordings, corresponding AFS reference copies, and identification numbers Appendix D: Complete listing of commercial recordings transferred to the Motion Picture, Broadcast, and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress 1 Collection Summary Call Number: AFC 1999/004 Creator: Eskin, Sam, 1898-1974 Title: The Sam Eskin Collection, 1938-1969 Contents: 469 containers; 56.5 linear feet; 16,568 items (15,795 manuscripts, 715 sound recordings, and 57 graphic materials) Repository: Archive of Folk Culture, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: This collection consists of materials gathered and arranged by Sam Eskin, an ethnomusicologist who recorded and transcribed folk music he encountered on his travels across the United States and abroad. From 1938 to 1952, the majority of Eskin’s manuscripts and field recordings document his growing interest in the American folk music revival. From 1953 to 1969, the scope of his audio collection expands to include musical and cultural traditions from Latin America, the British Isles, the Middle East, the Caribbean, and East Asia. -

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title American Tan: Modernism, Eugenics, and the Transformation of Whiteness Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/48g022bn Author Daigle, Patricia Lee Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara American Tan: Modernism, Eugenics, and the Transformation of Whiteness A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the History of Art and Architecture by Patricia Lee Daigle Committee in charge: Professor E. Bruce Robertson, Chair Professor Laurie Monahan Professor Jeanette Favrot Peterson September 2015 The dissertation of Patricia Lee Daigle is approved. __________________________________________ Laurie Monahan __________________________________________ Jeanette Favrot Peterson __________________________________________ E. Bruce Robertson, Chair August 2015 American Tan: Modernism, Eugenics, and the Transformation of Whiteness Copyright © 2015 by Patricia Lee Daigle iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In many ways, this dissertation is not only a reflection of my research interests, but by extension, the people and experiences that have influenced me along the way. It seems fitting that I would develop a dissertation topic on suntanning in sunny Santa Barbara, where students literally live at the beach. While at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), I have had the fortunate experience of learning from and working with several remarkable individuals. First and foremost, my advisor Bruce Robertson has been a model for successfully pursuing both academic and curatorial endeavors, and his encyclopedic knowledge has always steered me in the right direction. Laurie Monahan, whose thoughtful persistence attracted me to UCSB and whose passion for art history and teaching students has been inspiring. -

Publication 10 Part 2

Back Mountain It’s All Good News ...Covering the Back Mountain and surrounding communities! www.communitynewsonline.net Fun in the sun at JCC summer camp By: MB Gilligan Back Mountain Community News Correspondent Second, third and fourth grade girls and boys recently attended the Jewish Community Center summer camp at the Holiday House facility. The children participated in a program for their parents, grandparents, and friends recently at the camp, which included dancing to such hits as The Twist, Wipe Out, Kung Fu Fighting, Hawaiian Roller Coaster Ride and a beautiful rendition of hula dancing. Campers aged three through fourteen from throughout the Wyoming Valley have enjoyed a summer filled with typical camp activities like swimming, sports, biking, archery, and arts and crafts, as well as learning about the Jewish culture. Some of the boys who enjoyed this year’s JCC day camp are pictured with counselor Spencer Youngman. Enjoying pre-show preparations are, in front, from left: Diane Friedman, Sydney Barbini, Nia Lowe-Shaffer, Sinclaire Ogof, and Amelia Grudkowski, left, and Abby Santo, bothBuddies Cooper Wood, left, of Shavertown, and Annie Bagnall. In rear are counselors Ellen Matza and Sarah Sands. from Dallas, are dressed for the Hula Dance theyMark Hutsko, of Harvey’s Lake had a lot of fun performed at the show. together at the JCC Summer Camp. Community News • September 2010 • 2 Bear Den #3 scouts provided and served lunchDallas Lions Club installs club president to Habitat volunteers Recently, Pack 281, Bear Den #3 scouts provided and served lunch to the volunteers in Edwardsville at Habitat for Humanity. -

United States Bankruptcy Court

EXHIBIT A Exhibit A Service List Served as set forth below Description NameAddress Email Method of Service Adversary Parties A Group Of Citizens Westchester Putnam 388 168 Read Ave Tuckahoe, NY 10707-2316 First Class Mail Adversary Parties A Group Of Citizens Westchester Putnam 388 19 Hillcrest Rd Bronxville, NY 10708-4518 First Class Mail Adversary Parties A Group Of Citizens Westchester Putnam 388 39 7Th St New Rochelle, NY 10801-5813 First Class Mail Adversary Parties A Group Of Citizens Westchester Putnam 388 58 Bradford Blvd Yonkers, NY 10710-3638 First Class Mail Adversary Parties A Group Of Citizens Westchester Putnam 388 Po Box 630 Bronxville, NY 10708-0630 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Abraham Lincoln Council Abraham Lincoln Council 144 5231 S 6Th Street Rd Springfield, IL 62703-5143 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Abraham Lincoln Council C/O Dan O'Brien 5231 S 6Th Street Rd Springfield, IL 62703-5143 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Alabama-Florida Cncl 3 6801 W Main St Dothan, AL 36305-6937 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Alameda Cncl 22 1714 Everett St Alameda, CA 94501-1529 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Alamo Area Cncl#583 2226 Nw Military Hwy San Antonio, TX 78213-1833 First Class Mail Adversary Parties All Saints School - St Stephen'S Church Three Rivers Council 578 Po Box 7188 Beaumont, TX 77726-7188 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Allegheny Highlands Cncl 382 50 Hough Hill Rd Falconer, NY 14733-9766 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Aloha Council C/O Matt Hill 421 Puiwa Rd Honolulu, HI 96817 First