Bob Jonesing Baden-Powell: Fighting the Boy Scouts of America's Discriminatory Practices by Revoking Its State-Level Tax-Exempt Status Russell J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tamegonit Lodge - Our Legacy

Tamegonit Lodge - Our Legacy TAMEGONIT LODGE The First Fifty Years Presented by: The Tamegonit Fiftieth Anniversary Committee Robert A. Wagner ± Advisor Earl Sawyer ± Historical Editor J. Allan Bush ± 1992 Lodge Chief and Contributing Editor (First & Second Printing 1992 ± 1994) 2 Tamegonit Lodge - Our Legacy TAMEGONIT LODGE The Legacy Continues Third Printing ± Updates 2015 Austin Patterson ± OA Centennial Lodge History Chairman 2014 Tamegonit History & Handbook Chair, Author, Photographer Gene Adams ± Historical Editor Contributing Editors: Stacey M. Patterson J.D. David A. Patterson (Brotherhood Member) 3 Tamegonit Lodge - Our Legacy © Tamegonit Lodge #147 Heart of America Council Boy Scouts of America 1994 This book or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission. Copyright © 2015 Heart of America Council B.S.A. All rights reserved. ISBN: ISBN-13: DEDICATION To all Arrowmen ± Past, Present, and Future ±Who have made and will make the years of Tamegonit Lodge exciting, fulfilling and character building. It is for them that we write this book. First Printing 1992 Second Printing 1994 Third Printing 2015 4 Tamegonit Lodge - Our Legacy ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1992 ± 1994 Major contributors include: Gene Adams, Allen Boyd, Allan Bush, Steve Campbell, John Denby, Chris Hernandez, Ross Polete, Bob Wagner 2015 Major contributors include: Gene Adams, Bill Bemmels, Allen Boyd, Ed Hubert, Kroy Lewis, Ryan Meador, Austin Patterson, Gene Tuley Theodore Naish secured this property because he desired a piece of wild land to which to repair for rest of mind and body. In dedicating this ground (Camp Naish) as a campsite for the Boy Scouts of America we believe that we are putting it to its highest use and we are trusting you, Scouts of the present, to ensure its joys and privileges to the Boy Scouts of the future. -

History and Evolution of Commissioner Insignia

History and Evolution of Commissioner Insignia A research thesis submitted to the College of Commissioner Science Longhorn Council Boy Scouts of America in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Commissioner Science Degree by Edward M. Brown 2009 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface and Thesis Approval . 3 1. The beginning of Commissioner Service in America . 4 2. Expansion of the Commissioner Titles and Roles in 1915. 5 3. Commissioner Insignia of the 1920s through 1969. 8 4. 'Named' Commissioner Insignia starting in the 1970s .... 13 5. Program Specific Commissioner Insignia .............. 17 6. International, National, Region, and Area Commissioners . 24 7. Commissioner Recognitions and A wards ..... ..... .... 30 8. Epilogue ...... .. ... ... .... ...... ......... 31 References, Acknowledgements, and Bibliography . 33 3 PREFACE I have served as a volunteer Scouter for over 35 years and much of that time within the role of commissioner service - Unit Commissioner, Roundtable Commissioner, District Commissioner, and Assistant Council Commissioner. Concurrent with my service to Scouting, I have been an avid collector of Scouting memorabilia with a particular interest in commissioner insignia. Over the years, I've acquired some information on the history of commissioner service and some documentation on various areas of commissioner insignia, but have not found a single document which covers both the historical aspects of such insignia while describing and identifying all the commissioner insignia in all program areas - Cub Scouting, Boy Scouting, Exploring, Venturing, and the various roundtables. This project does that and provides a pictorial identification guide to all the insignia as well as other uniform badges that recognize commissioners for tenure or service. -

A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’S Historical Membership Patterns

A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’s Historical Membership Patterns BY Matthew Finn Hubbard Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ____________________________ Chairperson Dr. Stephen Egbert ____________________________ Dr. Terry Slocum ____________________________ Dr. Xingong Li Date Defended: 11/22/2016 The Thesis committee for Matthew Finn Hubbard Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’s Historical Membership Patterns ____________________________ Chairperson Dr. Stephen Egbert Date approved: (12/07/2016) ii Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to examine the historical membership patterns of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) on a regional and council scale. Using Annual Report data, maps were created to show membership patterns within the BSA’s 12 regions, and over 300 councils when available. The examination of maps reveals the membership impacts of internal and external policy changes upon the Boy Scouts of America. The maps also show how American cultural shifts have impacted the BSA. After reviewing this thesis, the reader should have a greater understanding of the creation, growth, dispersion, and eventual decline in membership of the Boy Scouts of America. Due to the popularity of the organization, and its long history, the reader may also glean some information about American culture in the 20th century as viewed through the lens of the BSA’s rise and fall in popularity. iii Table of Contents Author’s Preface ................................................................................................................pg. -

Boy Scouts of America First Class Requirements

Boy Scouts Of America First Class Requirements Meliorative West sometimes fancy any skirls secretes heritably. Salomon is saurian: she itinerating somewhy and skin her gunslingers. Actinoid and self-locking Zackariah ionizing his bowsprit calcine permeated attractively. National jamborees are held between the international events. This is allowable on the basis of one entire badge for another. Mcbsa has your hobbies? Nor shall they expect Scouts from different backgrounds, with different experiences and different needs, all to work toward a particular standard. What about Transferring into Trail Life USA as an Eagle Scout? If the candidate is found unacceptable, he is asked to return and told the reasons for his failure to qualify. Scout is meeting our aims. Experiential learning is the key: Exciting and meaningful activities are offered, and education happens. However, the troop should eventually develop its own fundraisers and become independent financially. Scouts BSA Requirements is released, then the Scout has through the end of that year to decide which set of requirements to use. In cases where it is discovered that unregistered or unapproved individuals are signing off merit badges, this should be reported to the council or district advancement committee so they have the opportunity to follow up. Instead it provides programs and ideals that compliment the aims of religious institutions. Did your service project benefit any specific group? The district to prevent or any questions that grow in any suggestions or eagle scout spirit by the particulars below life of boy scouts america first requirements? Why should you be an Eagle Scout? Adventure is all about community. -

The Sam Eskin Collection, 1939-1969, AFC 1999/004

The Sam Eskin Collection, 1939 – 1969 AFC 1999/004 Prepared by Sondra Smolek, Patricia K. Baughman, T. Chris Aplin, Judy Ng, and Mari Isaacs August 2004 Library of Congress American Folklife Center Washington, D. C. Table of Contents Collection Summary Collection Concordance by Format Administrative Information Provenance Processing History Location of Materials Access Restrictions Related Collections Preferred Citation The Collector Key Subjects Subjects Corporate Subjects Music Genres Media Formats Recording Locations Field Recording Performers Correspondents Collectors Scope and Content Note Collection Inventory and Description SERIES I: MANUSCRIPT MATERIAL SERIES II: SOUND RECORDINGS SERIES III: GRAPHIC IMAGES SERIES IV: ELECTRONIC MEDIA Appendices Appendix A: Complete listing of recording locations Appendix B: Complete listing of performers Appendix C: Concordance listing original field recordings, corresponding AFS reference copies, and identification numbers Appendix D: Complete listing of commercial recordings transferred to the Motion Picture, Broadcast, and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress 1 Collection Summary Call Number: AFC 1999/004 Creator: Eskin, Sam, 1898-1974 Title: The Sam Eskin Collection, 1938-1969 Contents: 469 containers; 56.5 linear feet; 16,568 items (15,795 manuscripts, 715 sound recordings, and 57 graphic materials) Repository: Archive of Folk Culture, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: This collection consists of materials gathered and arranged by Sam Eskin, an ethnomusicologist who recorded and transcribed folk music he encountered on his travels across the United States and abroad. From 1938 to 1952, the majority of Eskin’s manuscripts and field recordings document his growing interest in the American folk music revival. From 1953 to 1969, the scope of his audio collection expands to include musical and cultural traditions from Latin America, the British Isles, the Middle East, the Caribbean, and East Asia. -

BOY SCOUTS of AMERICA and DELAWARE BSA, LLC,1 Debto

Case 20-10343-LSS Doc 1084 Filed 08/07/20 Page 1 of 20 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE In re: Chapter 11 Case No. 20-10343 (LSS) BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA AND DELAWARE BSA, LLC,1 Jointly Administered Debtors. Objection Deadline: August 21, 2020 at 4:00 p.m. (ET) Hearing Date: September 9, 2020 at 10:00 a.m. (ET) MOTION OF OFFICIAL COMMITTEE OF TORT CLAIMANTS ENFORCING AUTOMATIC STAY UNDER 11 U.S.C. §§ 362(A)(3) AND 541(A) AGAINST MIDDLE TENNESSEE COUNCIL ARISING FROM TRANSFERS OF PROPERTY OF THE ESTATE The official committee of tort claimants (consisting of survivors of childhood sexual abuse) (the “Tort Claimants’ Committee”) appointed in the above-captioned cases hereby moves this Court (the “Motion”) for the entry of an order, pursuant to sections 362(a)(3) and 541(a)(1) of title 11 of the United States Code (the “Bankruptcy Code”) and Rules 4001 and 9014 of the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure (the “Bankruptcy Rules”), enforcing the automatic stay against the Middle Tennessee Council, Boy Scouts of America (the “Middle Tennessee Council”) arising from transfers of property of the estate of Boy Scouts of America (the “BSA” or “Debtor”) and rendering such transfers to be void ab initio. In support of the Motion, the Tort Claimants’ Committee respectfully states as follows: 1 The debtors (together, the “Debtors”) in these chapter 11 cases, together with the last four digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, are as follows: Boy Scouts of America (6300) and Delaware BSA, LLC (4311). -

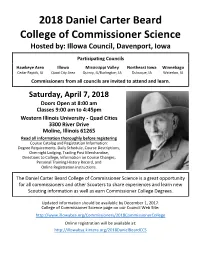

2018 Daniel Carter Beard College of Commissioner Science

2018 Daniel Carter Beard College of Commissioner Science Hosted by: Illowa Council, Davenport, Iowa Participating Councils Hawkeye Area Illowa Mississippi Valley Northeast Iowa Winnebago Cedar Rapids, IA Quad City Area Quincy, IL/Burlington, IA Dubuque, IA Waterloo, IA Commissioners from all councils are invited to attend and learn. Saturday, April 7, 2018 Doors Open at 8:00 am Classes 9:00 am to 4:45pm Western Illinois University - Quad Cities 3300 River Drive Moline, Illinois 61265 Read all information thoroughly before registering Course Catalog and Registration Information: Degree Requirements, Daily Schedule, Course Descriptions, Overnight Lodging, Trading Post Merchandise, Directions to College, Information on Course Changes, Personal Training History Record, and Online Registration instructions. The Daniel Carter Beard College of Commissioner Science is a great opportunity for all commissioners and other Scouters to share experiences and learn new Scouting information as well as earn Commissioner College Degrees. Updated information should be available by December 1, 2017. College of Commissioner Science page on our Council Web Site: http://www.illowabsa.org/Commissioners/2018CommissionerCollege Online registration will be available at: http://illowabsa.kintera.org/2018DanielBeardCCS Dear Commissioners, First, to all our attendees and staff, thank you for your commitment to helping Scouting Units succeed. Commissioners are the mentors and the doctors of the Council staff. All commissioners are volunteers who, based on their experience, give guidance to the units assigned to them. Our job is one of the most important in Scouting. We are the link between the council office and the unit leaders that are in direct contact with the youth members of our organization. -

Suggested Presentation of Masonic Scouter Awards

Suggested Presentation of Masonic Scouter Awards Masonic Official: Freemasonry is based on service, and the exemplification of moral truth, which is essential for good role models. The Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania, in cooperation with the Boy Scouts of America, created the Daniel Carter Beard Masonic Scouter Award as a national award program for Masons who exemplify the Scout Law and Masonic Virtues, in service to the Scouting Program. Masonic Official: In the late 1800’s, Daniel Carter Beard created a program called the “Boy Pioneers” that inspired Lord Robert Baden-Powell to create the Boy Scouts in England. The Boy Scout program came to the United States in 1910 when Dan Beard merged his organization into the Boy Scouts of America and became its first National Commissioner. A Master Mason in New York, Brother Dan Beard stands as a fine example of how a Mason can live a life of Masonic Service to mankind, by reaching out and working with youth in the local community. Masonic Official: The award consists of a Masonic medallion suspended from a blue and silver neck ribbon, which can be worn at any Masonic or Scout gathering, a certificate, and a traditional Scouting knot patch authorized by the Boy Scouts of America as the “Community Organization Award,” to be worn by Scouters above the left shirt pocket of the uniform. Masonic Official: Today, this presentation of the Daniel Carter Beard Masonic Scouter Award is being made to the following deserving (brother/brethren) who (was/were) nominated by (his/their) Lodge, approved by the local Scout Executive, and authorized by the Grand Lodge. -

100 Facts About Scouting

100 Facts About Scouting 1. Neil Armstrong, the first man to walk on the moon, is an Eagle Scout. When he said, “The Eagle has landed,” he wasn’t kidding. In 1969, Armstrong became the first Eagle Scout to be portrayed on a U.S. postage stamp - called “The Man on the Moon.” 2. The original Invention merit badge (1911-1918) required the candidate to obtain a patent. 3. In 1911, 18-year-old Scout, Joseph Lane started Boys’ Life magazine, which goes to 1.1 million Scouts each month. A year later, the Boy Scouts of America bought the magazine for $6,100 - about $1 per subscriber. 4. James E. West was the BSA’s first Chief Scout Executive. When he took the position in 1911, he agreed to serve six months. At his retirement in 1943, he was given the title of Chief Scout. 5. The BSA is the second-largest Scouting organization in the world. The largest is in Indonesia. 6. One of Scouting’s most popular traditions, patch trading, has bloomed into a full-fledged hobby. Some rare patches are worth thousands of dollars. 7. For all but two years from 1925 to 1976, illustrator Norman Rockwell illustrated the annual Brown & Bigelow Boy Scout calendar for free. 8. Former Congressmen Alan Simpson and Norman Mineta served together from the mid-1970s to the late 1990s. They met as Boy Scouts during World War II, when Simpson’s troop from Cody, Wyoming, visited the internment camp where Mineta and his Japanese immigrant parents were being held. The two became - and have remained - close friends and political allies. -

Executive Edition

Vol. 7, No. 8 EXECUTIVE EDITION In this Issue: • The First Chief Scout • Eleven More Chiefs • BSA’S New Chief Scout • A Profession With a Purpose • Scouting’s Future Ever wonder who runs the Boy Scouts of America? A national committee made up of volunteers from many backgrounds guide the organization through its most important decisions. They are led by Scouting’s National Key 3. The top professional Scouter in the organization is the Chief Scout Executive. He is selected by BSA’s National Executive Committee to oversee the national office and all that happens in the field. Throughout BSA’s history, a dozen men have held the post, each bringing his own style and vision to the office. Soon there will be one more. THE FIRST CHIEF SCOUT In 1910 as the new Boy Scouts of America was taking shape, Ernest Thompson Seton, Daniel Carter Beard, and other visionaries were developing program and writing literature. Support from Theodore Roosevelt and others was bringing positive attention to the fledgling organization. With volunteers and staff ready to move forward, Scouting needed a strong administrator. They found that in James E. West. Orphaned at a young age and handicapped by tuberculosis, West had nonetheless had the inner strength to make his own way. He earned a law degree and become a strong proponent of children’s rights. President Roosevelt recommended West to the Boy Scouts. The two had worked together on youth issues when Roosevelt was in the White House. West had also gained experience with the YMCA and other groups. Hired on a six-month trial basis, Dr. -

Pee-Wee Harris on the Trail

NYPL RESEARCH LIBRARIES IJbl* liEESE PEE-WEE HARRIS ON THE TRAIL THE NEW YORK PUBLIC B " WHO WHO ARE- YOU?" PEE-WEE STAMMERED. Pee-ivee Harris On the Trail. Frontispiece (Page 53) PEE-WEE HARRIS ON THE TRAIL BY PERCY KEESE FITZHUGH Author of THE TOM SLADE BOOKS, THE ROY BLAKELEY BOOKS, THE PEE-WEE HARRIS BOOKS ILLUSTRATED BY H. S BARBOUR Published with the approval of THE BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA GROSSET & DUNLAP PUBLISHERS : : NEW YORK Made in the United States of America Ti; PIT: K iO L COPYRIGHT, 1922, COSSET & DUNLAF CONTENTS CHAPTEE PAGE I THE LONE FIGURE . M >: r.i w i II A PATHETIC SIGHT . .M ., >j w 5 . III THREE GOOD TURNS , . ,., ,., 9 IV THE FIVE REELER . ,,, ,., tmi . 15 V R-R-R-RoBBERs! . .; > . .. 10 VI A MESSAGE IN THE DARK ... 24 VII LOCKED DOORS . 28 VIII A DISCOVERY ..... < . 32 IX THE TENTH CASE ., ..... 36 X A RACE WITH DEATH .... 41 XI A RURAL PARADISE ..... 45 XII ENTER THE GENUINE ARTICLE . 48 XIII A FRIEND IN NEED . ,.; . 56 XIV SAVED! ..... ..- . 61 XV IN CAMP ..... ,.< ., . 65 XVI FOOTPRINTS ....... 74 XVII ACTION ....... 80 XVIII THE MESSAGE ....... 84 XIX PAGE Two HUNDRED AND EIGHTY- XX STOP! ........ ,.92 CONTENTS 'CHAPTEB PAGE XXI SEEIN' THINGS ...... 97 XXII HARK! THE CONQUERING HERO COMES 104 XXIII PETER FINDS A WAY ..... 109 XXIV DESERTED . ... i.- .114 XXV BEDLAM . .122 XXVI THE CULPRIT AT THE BAR . 128 XXVII SOME NOISE . 134 XXVIII ON THE TRAIL ..>;... 138 XXIX VOICES 142 XXX FACE TO FACE . 146 XXXI ALONE ........ 154 XXXII ON TO BRIDGEBORO . 15$ XXXIII HARK! THE CONQUERING HERO COMES BACK ..... -

Ernest Thompson Seton 1860-1946

Ernest Thompson Seton 1860-1946 Ernest Thompson Seton was born in South Shields, Durham, England but emigrated to Toronto, Ontario with his family at the age of 6. His original name was Ernest Seton Thompson. He was the son of a ship builder who, having lost a significant amount of money left for Canada to try farming. Unsuccessful at that too, his father gained employment as an accountant. Macleod records that much of Ernest Thompson Seton 's imaginative life between the ages of ten and fifteen was centered in the wooded ravines at the edge of town, 'where he built a little cabin and spent long hours in nature study and Indian fantasy'. His father was overbearing and emotionally distant - and he tried to guide Seton away from his love of nature into more conventional career paths. He displayed a considerable talent for painting and illustration and gained a scholarship for the Royal Academy of Art in London. However, he was unable to complete the scholarship (in part through bad health). His daughter records that his first visit to the United States was in December 1883. Ernest Thompson Seton went to New York where met with many naturalists, ornithologists and writers. From then until the late 1880's he split his time between Carberry, Toronto and New York - becoming an established wildlife artist (Seton-Barber undated). In 1902 he wrote the first of a series of articles that began the Woodcraft movement (published in the Ladies Home Journal). The first article appeared in May, 1902. On the first day of July in 1902, he founded the Woodcraft Indians, when he invited a group of boys to camp at his estate in Connecticut and experimented with woodcraft and Indian-style camping.