Practical Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Novelties in the Hornwort Flora of Croatia and Southeast Europe

cryptogamie Bryologie 2019 ● 40 ● 22 DIRECTEUR DE LA PUBLICATION : Bruno David, Président du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle RÉDACTEURS EN CHEF / EDITORS-IN-CHIEF : Denis LAMY ASSISTANTS DE RÉDACTION / ASSISTANT EDITORS : Marianne SALAÜN ([email protected]) MISE EN PAGE / PAGE LAYOUT : Marianne SALAÜN RÉDACTEURS ASSOCIÉS / ASSOCIATE EDITORS Biologie moléculaire et phylogénie / Molecular biology and phylogeny Bernard GOFFINET Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut (United States) Mousses d’Europe / European mosses Isabel DRAPER Centro de Investigación en Biodiversidad y Cambio Global (CIBC-UAM), Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (Spain) Francisco LARA GARCÍA Centro de Investigación en Biodiversidad y Cambio Global (CIBC-UAM), Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (Spain) Mousses d’Afrique et d’Antarctique / African and Antarctic mosses Rysiek OCHYRA Laboratory of Bryology, Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences, Krakow (Pologne) Bryophytes d’Asie / Asian bryophytes Rui-Liang ZHU School of Life Science, East China Normal University, Shanghai (China) Bioindication / Biomonitoring Franck-Olivier DENAYER Faculté des Sciences Pharmaceutiques et Biologiques de Lille, Laboratoire de Botanique et de Cryptogamie, Lille (France) Écologie des bryophytes / Ecology of bryophyte Nagore GARCÍA MEDINA Department of Biology (Botany), and Centro de Investigación en Biodiversidad y Cambio Global (CIBC-UAM), Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (Spain) COUVERTURE / COVER : Extraits d’éléments de la Figure 2 / Extracts of -

Phytotaxa, a Synthesis of Hornwort Diversity

Phytotaxa 9: 150–166 (2010) ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ Article PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2010 • Magnolia Press ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) A synthesis of hornwort diversity: Patterns, causes and future work JUAN CARLOS VILLARREAL1 , D. CHRISTINE CARGILL2 , ANDERS HAGBORG3 , LARS SÖDERSTRÖM4 & KAREN SUE RENZAGLIA5 1Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut, 75 North Eagleville Road, Storrs, CT 06269; [email protected] 2Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian National Herbarium, Australian National Botanic Gardens, GPO Box 1777, Canberra. ACT 2601, Australia; [email protected] 3Department of Botany, The Field Museum, 1400 South Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL 60605-2496; [email protected] 4Department of Biology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, N-7491 Trondheim, Norway; [email protected] 5Department of Plant Biology, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL 62901; [email protected] Abstract Hornworts are the least species-rich bryophyte group, with around 200–250 species worldwide. Despite their low species numbers, hornworts represent a key group for understanding the evolution of plant form because the best–sampled current phylogenies place them as sister to the tracheophytes. Despite their low taxonomic diversity, the group has not been monographed worldwide. There are few well-documented hornwort floras for temperate or tropical areas. Moreover, no species level phylogenies or population studies are available for hornworts. Here we aim at filling some important gaps in hornwort biology and biodiversity. We provide estimates of hornwort species richness worldwide, identifying centers of diversity. We also present two examples of the impact of recent work in elucidating the composition and circumscription of the genera Megaceros and Nothoceros. -

Anthocerotophyta

Glime, J. M. 2017. Anthocerotophyta. Chapt. 2-8. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 1. Physiological Ecology. Ebook 2-8-1 sponsored by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 5 June 2020 and available at <http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/>. CHAPTER 2-8 ANTHOCEROTOPHYTA TABLE OF CONTENTS Anthocerotophyta ......................................................................................................................................... 2-8-2 Summary .................................................................................................................................................... 2-8-10 Acknowledgments ...................................................................................................................................... 2-8-10 Literature Cited .......................................................................................................................................... 2-8-10 2-8-2 Chapter 2-8: Anthocerotophyta CHAPTER 2-8 ANTHOCEROTOPHYTA Figure 1. Notothylas orbicularis thallus with involucres. Photo by Michael Lüth, with permission. Anthocerotophyta These plants, once placed among the bryophytes in the families. The second class is Leiosporocerotopsida, a Anthocerotae, now generally placed in the phylum class with one order, one family, and one genus. The genus Anthocerotophyta (hornworts, Figure 1), seem more Leiosporoceros differs from members of the class distantly related, and genetic evidence may even present -

Morphology, Anatomy and Reproduction of Anthoceros

Morphology, Anatomy and Reproduction of Anthoceros - INDRESH KUMAR PANDEY Taxonomic Position of Anthoceros Class- Anthocerotopsida Single order Anthocerotales Two families Anthocerotaceae Notothylaceae Representative Genus Anthoceros Notothylus General features of Anthocerotopsida • Forms an isolated evolutionary line • Sometimes considered independent from Bryophytes and placed in division Anthocerophyta • Called as Hornworts due to horn like structure of sporophyte • Commonly recognised genera includes Anthoceros, Megaceros, Nothothylus, Dendroceros Anthoceros :Habitat & Distribution • Cosmopolitan • Mainly in temperate & tropical regions • More than 200 species, 25 sp. Recorded from India. • Mostly grows in moist shady places, sides of ditches or in moist hollows among rocks • Few species grow on decaying wood. • Three common Indian species- A. erectus, A. crispulus, A. himalayensis Anthoceros: Morphology Dorsal surface Ventral surface Rhizoids (smooth walled) Thallus showing tubers External features • Thallus (gametophyte)- small, dark green, dorsiventral, prostrate, branched or lobed • No midrib, spongy due to presence of underlying mucilaginous ducts • Dorsal surface varies from species to species Smooth- A. laevis Velvety- A. crispulus Rough- A. fusiformis • Smooth walled rhizoid on ventral surface • Rounded bluish green thickened area on ventral surface- Nostoc colonies Internal structure Vertical Transverse Section- Diagrammatic Vertical Transverse Section- Cellular Internal Structure • Simple, without cellular differentiation -

Establishment of Anthoceros Agrestis As a Model Species for Studying the Biology of Hornworts

Szövényi et al. BMC Plant Biology (2015) 15:98 DOI 10.1186/s12870-015-0481-x METHODOLOGY ARTICLE Open Access Establishment of Anthoceros agrestis as a model species for studying the biology of hornworts Péter Szövényi1,2,3,4†, Eftychios Frangedakis5,8†, Mariana Ricca1,3, Dietmar Quandt6, Susann Wicke6,7 and Jane A Langdale5* Abstract Background: Plants colonized terrestrial environments approximately 480 million years ago and have contributed significantly to the diversification of life on Earth. Phylogenetic analyses position a subset of charophyte algae as the sister group to land plants, and distinguish two land plant groups that diverged around 450 million years ago – the bryophytes and the vascular plants. Relationships between liverworts, mosses hornworts and vascular plants have proven difficult to resolve, and as such it is not clear which bryophyte lineage is the sister group to all other land plants and which is the sister to vascular plants. The lack of comparative molecular studies in representatives of all three lineages exacerbates this uncertainty. Such comparisons can be made between mosses and liverworts because representative model organisms are well established in these two bryophyte lineages. To date, however, a model hornwort species has not been available. Results: Here we report the establishment of Anthoceros agrestis as a model hornwort species for laboratory experiments. Axenic culture conditions for maintenance and vegetative propagation have been determined, and treatments for the induction of sexual reproduction and sporophyte development have been established. In addition, protocols have been developed for the extraction of DNA and RNA that is of a quality suitable for molecular analyses. -

About the Book the Format Acknowledgments

About the Book For more than ten years I have been working on a book on bryophyte ecology and was joined by Heinjo During, who has been very helpful in critiquing multiple versions of the chapters. But as the book progressed, the field of bryophyte ecology progressed faster. No chapter ever seemed to stay finished, hence the decision to publish online. Furthermore, rather than being a textbook, it is evolving into an encyclopedia that would be at least three volumes. Having reached the age when I could retire whenever I wanted to, I no longer needed be so concerned with the publish or perish paradigm. In keeping with the sharing nature of bryologists, and the need to educate the non-bryologists about the nature and role of bryophytes in the ecosystem, it seemed my personal goals could best be accomplished by publishing online. This has several advantages for me. I can choose the format I want, I can include lots of color images, and I can post chapters or parts of chapters as I complete them and update later if I find it important. Throughout the book I have posed questions. I have even attempt to offer hypotheses for many of these. It is my hope that these questions and hypotheses will inspire students of all ages to attempt to answer these. Some are simple and could even be done by elementary school children. Others are suitable for undergraduate projects. And some will take lifelong work or a large team of researchers around the world. Have fun with them! The Format The decision to publish Bryophyte Ecology as an ebook occurred after I had a publisher, and I am sure I have not thought of all the complexities of publishing as I complete things, rather than in the order of the planned organization. -

02-Bryophyta-2.Pdf

498 INTRODUCTORY PLANT SCIENCE layer. In certain species, the capsule con til1Ues to grow as long as the gametophyte lives. The presence of a meristcm in A11tlioceros and an aerating system complete with sto mata may indicate that Antlwceros evolved from ancestors with even ·larger· and more 1. Civ complex sporophytes. These features may Bryophyt be vestiges from a more complex ancestral. 2. Wh sporophyte. that ti alga ? 3. De� ORIGIN AND RELATIONSHIPS OF THE Bryophyt, BRYOPHYTA 4._ characteri Little is known with certainty about the r are small origin and evolution of the bryophytes. The ' tall. ( B) fossil record is too fragmenta to enable • ry s true roots us to trace their evolutionary history. Frag ,, sperms ar mentary remnants of thallose liverworts, spore idium and mother\4'/ttN) which resemble present-day liverworts, have cell Jar arch� been foum! in rocks of Carboniferous age, bryophyt as have structures that may be remains of more com mosses. all bryoph The immediate ancestors of the bryo bryo whicl phytes were probably more complex plants from the have an i than present-day forms. In other words, the gametophy evolutionary tendency has been one of re- with a dip1 duction instead of increased complexity. •• • • • spores If evolution has progressed . from more • . •, .... • s. __ complex sporophytes to those of simpler • . vascular p Anthoceros . form, the sporophyte of wou1d • • green algat be considered more ancient than that of • (D) red Marchantia or Riccia. Because Riccia has Fig. 35-16. longitudinal section of the spo 6. How the most reduced sporophyte, it would be t·:i;,hyte of Anthoceros. -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

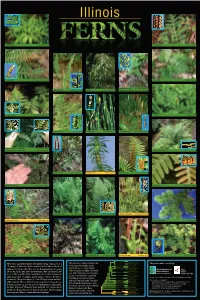

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

Mosses and Ferns

Mosses and Ferns • How did they evolve from Protists? Moss and Fern Life Cycles Group 1: Seedless, Nonvascular Plants • Live in moist environments to reproduce • Grow low to ground to retain moisture (nonvascular) • Lack true leaves • Common pioneer species during succession • Gametophyte most common (dominant) • Ex: Mosses, liverworts, hornworts Moss Life Cycle 1)Moss 2) Through water, 3) Diploid sporophyte 4) Sporophyte will gametophytes sperm from the male will grow from zygote create and release grow near the gametophyte will haploid spores ground swim to the female (haploid stage) gametophyte to create a diploid zygote Diploid sporophyte . zygo egg zygo te egg te zygo zygo egg egg te te male male female female female male female male Haploid gametophytes 5) Haploid 6) The process spores land repeats and grow into new . gametophytes . Haploid gametophytesground . sporophyte . zygo egg zygo te egg te zygo zygo egg egg te te male male female female female male female male Haploid gametophytes • Vascular system allows Group 2: Seedless, – Taller growth – Nutrient transportation Vascular Plants • Live in moist environments – swimming sperm • Gametophyte stage – Male gametophyte: makes sperm – Female gametophyte: makes eggs – Sperm swims to fertilize eggs • Sporophyte stage – Spores released into air – Spores land and grow into gametophyte • Ex: Ferns, Club mosses, Horsetails Fern Life Cycle 1) Sporophyte creates and releases haploid spores Adult Sporophyte . ground 2) Haploid spores land in the soil . ground 3) From the haploid spores, gametophyte grows in the soil Let’s zoom in Fern gametophytes are called a prothallus ground 4) Sperm swim through water from the male parts (antheridium) to the female parts (archegonia)…zygote created Let’s zoom back out zygo zygo egg egg te te zygo egg te 5) Diploid sporophyte grows from the zygote sporophyte Fern gametophytes are called a prothallus ground 6) Fiddle head uncurls….fronds open up 7) Cycle repeats -- Haploid spores created and released . -

Plant Reproduction

AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education Page 1 of 10 www.accessscience.com Plant reproduction Contributed by: Scott D. Russell Publication year: 2014 The formation of a new plant that is either an exact copy or recombination of the genetic makeup of its parents. There are three types of plant reproduction considered here: (1) vegetative reproduction, in which a vegetative organ forms a clone of the parent; (2) asexual reproduction, in which reproductive components undergo a nonsexual form of production of offspring without genetic rearrangement, also known as apomixis; and (3) sexual reproduction, in which meiosis (reduction division) leads to formation of male and female gametes that combine through syngamy (union of gametes) to produce offspring. See also: PLANT; PLANT PHYSIOLOGY. Vegetative reproduction Unlike animals, plants may be readily stimulated to produce identical copies of themselves through cloning. In animals, only a few cells, which are regarded as stem cells, are capable of generating cell lineages, organs, or new organisms. In contrast, plants generate or produce stem cells from many plant cells of the root, stem, or leaf that are not part of an obvious generative lineage—a characteristic that has been known as totipotency, or the general ability of a single cell to regenerate a whole new plant. This ability to establish new plants from one or more cells is the foundation of plant biotechnology. In biotechnology, a single cell may be used to regenerate new organisms that may or may not genetically differ from the original organism. If it is identical to the parent, it is a clone; however, if this plant has been altered through molecular biology, it is known as a genetically modified organism (GMO). -

UNIT 4 REPRODUCTION in ALGAE Structure 4.1 Introduction Ol?Jeclives

UNIT 4 REPRODUCTION IN ALGAE Structure 4.1 Introduction Ol?jeclives 4.2 Types of Reproduction ' Veghtivc l<cproduction Asexual Reproduction Sexual Reproduction 4.3 Reproductio~iand Life Cycle C'lilar~~ydo~~~onus ~l/o/liri.~ ~I/\~u Lai~iinorrcr , P rrcrrJ 4.4 Origin and Evolution of Sex Origin of Sex E:volution of Scx 4.5 Summary 4.6 Terminal Questions 4.7 Answers. 4.1 INTRODUCTION In unit 3 you have learnt that algae vary in size from small microscopic unicellular forms like Chlanzydonionas to large macroscopic multicellular forms like Lanzinaria. The multicellular forms show great diversity in their organisation and include filamentous. heterotrichous, thalloid and polysiphonoid forms. In this unit we will discuss the types ofreproduction and life cycle in algae taking suitable representative examples from various groups. Algae show all the three types of reproduction vegetative, asexual and sexual. Vegetative method solely depend on the capacity of bits of algae accidentally broken to produce a new one by simple cell division. Asexual methods on the other hand involve production of new type of cells, zoospores. In sexual reproduction gametes are formed. They fuse in pairs to form zygote. Zygote may divide and produce a new thallus or it may secrete a thick wall to form a zygospore. What controls sexi~aldifferentiation, attraction of gametes towards each other and determination of maleness or femaleness of ga~netes?We will discuss this aspect also. Yog will see that sexual reproduction in algae has many interesting features which also throw light on the origin and evolution of sex in plants. -

Structure & Life History of Fucus

B.Sc. Part I - Subsidiary Dept. of Botany Dr. R. K. Sinha Structure & Life history of Fucus Family Fucaceae: Plants are dichotomous or pinnate strap-shaped simple or with costate branches, in some cases with piliferous cryptostomata, often with buoyant air bladders. Receptacular portions of the thallus terminate main branches or form stalked lateral branch- lets, heterogamous to oogamous. Each oogonium forms several eggs. Genus Fucus of Fucaceae: This is a common marine alga containing a number of species that are widely distributed in the sea coasts of temperate and Arctic regions. Most species are found attached to rocks between low and high tide marks and are commonly known as rock- weeds. The plant body of Fucus consists of a leathery, parenchymatous, dichotomously branched ribbon-like frond, stem-like stipe and a basal disc-like holdfast or hapteron by which it is attached to the substratum (Fig. 109A). The plants may be attached to completely or partly submerged rocks. The thallus is buoyed up in water by ‘air vesicles, or bladder-like structures or floats. The swollen tips of the thalli, the receptacles, which lack midrib, are covered with small scattered pimple-like projections with small openings which lead into cavities, known as conceptacles (Fig. 109B). The thallus is diploid, may be monoecious or dioecious and is characterized by anatomical complexity. The thallus has a peripheral layer, which is known as the limiting layer, composed of small cells containing abundant plastids and performing the function of assimilation (Fig. 109G). Below this is the cortex of several layers of elongated mucilaginous parenchymatous cells probably forming the storage system.