Moving Images – Static Spaces: Architectures, Art, Media, Film, Digital Art and Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

INDEX COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL JJWBT370_index.inddWBT370_index.indd 175175 88/30/10/30/10 88:23:22:23:22 PMPM JJWBT370_index.inddWBT370_index.indd 176176 88/30/10/30/10 88:23:22:23:22 PMPM A Billabong, 23 Access Hollywood, 56 Birdhouse Projects Activision Blitz fi nances impacting, 80–81 900 Films advertising creation for, 96 early days of, 15–17, 77–78 Boom Boom HuckJam sponsorship by, Hawk buy-out of, 81–82 56–57 video/fi lm involvement by, 19, 87–96 (see Tony Hawk video game designed/released also 900 Films) by, 6–7, 25–26, 36–43, 56–57, Black, Jack, 108 68–69, 73, 132, 140 (see Video Black Pearl Skatepark grand opening, games for detail) 134–136 Secret Skatepark Tour support from, 140 Blink-182, 133, 161, 162 skateboard controller designed by, 41–43 Blitz Distribution Tony Hawk Foundation contributions denim clothing investment by, 77–80 from, 158 fi nances of, 78–81 Adio Tour, 130–131 Hawk Clothing involvement offer to, 24 Adoptante, Clifford, 51, 55 Hawk relinquishing shares in, 82 Agassi, Andre, 132, 162–163 legal issues for, 17–19 Anderson, Pamela, 134, 162 skate team/company support by, 77 Antinoro, Mike, 71 video/fi lm involvement of, 90 Apatow, Judd, 107 Blogs, 99–104, 106 Apple iPhone, 91, 99–102 BMX Are You Smarter Than a 5th Grader?, 157, 158 Boom Boom HuckJam inclusion of, 48, Armstrong, Lance, 103, 108, 162 49, 51, 55–56, 58–59, 67 Athens, Georgia, 142 charitable fundraisers including, 133–134, Awards 161 MTV Video Music Awards, 131–132 Froot Loops’ endorsement including, 3, 4 Nickelodeon Kids’ Choice Awards, 7, 146 product merchandising -

Etnies Album Download Free Etnies Album Download Free

etnies album download free Etnies album download free. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67da3abdce05c41a • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Etnies album download free. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67da3abdadc384d4 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. -

I. Race, Gender, and Asian American Sporting Identities

I. Race, Gender, and Asian American Sporting Identities Dat Nguyen is the only Vietnamese American drafted by a National Football League team. He was an All-American at Texas A & M University (1998) and an All-Pro for the Dallas Cowboys (2003). Bookcover image: http://www.amazon.com/Dat-Tackling-Life-NFL-Nguyen/dp/1623490634 Truck company Gullwing featured two Japanese Americans in their platter of seven of their “hottest skaters,” Skateboarder Magazine, January 1979. 2 Amerasia Journal 41:2 (2015): 2-24 10.17953/ aj.41.2.2 Skate and Create Skateboarding, Asian Pacific America, and Masculinity Amy Sueyoshi In the early 1980s, my oldest brother, a senior in high school, would bring home a different girl nearly every month, or so the family myth goes. They were all white women, punkers in leath- er jackets and ripped jeans who exuded the ultimate in cool. I thought of my brother as a rock star in his ability to attract so many edgy, beautiful women in a racial category that I knew at the age of nine was out of our family’s league. As unique as I thought my brother’s power of attraction to be, I learned later that numerous Asian stars rocked the stage in my brother’s world of skateboarding. A community of intoxicatingly rebellious Asian and Pacific Islander men thrived during the 1970s and 1980s within a skater world almost always characterized as white, if not blatantly racist. These men’s positioning becomes particularly notable during an era documented as a time of crippling emas- culation for Asian American men. -

Masaryk University Brno

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English language and literature The origin and development of skateboarding subculture Bachelor thesis Brno 2017 Supervisor: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. author: Jakub Mahdal Bibliography Mahdal, Jakub. The origin and development of skateboarding subculture; bachelor thesis. Brno; Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, Department of English Language and Literature, 2017. NUMBER OF PAGES. The supervisor of the Bachelor thesis: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. Bibliografický záznam Mahdal, Jakub. The origin and development of skateboarding subculture; bakalářská práce. Brno; Masarykova univerzita, Pedagogická fakulta, Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury, 2017. POČET STRAN. Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. Abstract This thesis analyzes the origin and development of skateboarding subculture which emerged in California in the fifties. The thesis is divided into two parts – a theoretical part and a practical part. The theoretical part introduces the definition of a subculture, its features and functions. This part further describes American society in the fifties which provided preconditions for the emergence of new subcultures. The practical part analyzes the origin and development of skateboarding subculture which was influenced by changes in American mass culture. The end of the practical part includes an interconnection between the values of American society and skateboarders. Anotace Tato práce analyzuje vznik a vývoj skateboardové subkultury, která vznikla v padesátých letech v Kalifornii. Práce je rozdělena do dvou částí – teoretické a praktické. Teoretická část představuje pojem subkultura, její rysy a funkce. Tato část také popisuje Americkou společnost v 50. letech, jež poskytla podmínky pro vznik nových subkultur. -

Individual and Community Culture at the Notorious Burnside Skatcpark Hames Ellerbe Universi

Socially Infamous Socially Infamous: Individual and Community Culture at the Notorious Burnside Skatcpark Hames Ellerbe University of Oregon A master's research project Presented to the Arts and Administration Program of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Arts Administration Socially Infamous iii Approved by: Arts and Administration Program University of Oregon Socially Infamous V Abstract and Key Words Ahslracl This research project involves sociocultural validation of the founding members and early participants of Burnside Skatepark. The group developed socioculturally through the creation and use of an internationally renowned Do fl Yourse{l(DIY) skatepark. Located under the east side of the Burnside Bridge in Portland, Oregon and founded in 1990, Burnside Skatepark is one of the most famous skateparks in the world, infamous for territorialism, attitude, and difficulty. On the other hand, the park has been built with dedication, devoid ofcity funding and approval, in an area known, in the earlier days of the park, as a crime infested, former industrial district. Through the do ii yourselfcreation of Burnside skatepark, came the sociocultural cultivation and development of the founding participants and skaters. Additionally, the creation of the park provided substantial influence in the sociocultural development of a number of professional skateboarders and influenced the creation of parks worldwide. By identifying the sociocultural development and cultivation of those involved with the Burnside skatepark, specifically two of the founders, and one professional skateboarder, consideration can be provided into how skateboarding, creating a space, and skate participation may lead to significant development of community, social integrity, and self-worth even in the face of substantial gentrification. -

By Monty Little Were No Doubt the Best on Your Block

efore the days of the ollie, you measured the skill level of a skateboarder by how many 360s he (or she) could do. As Bspinning required balance, power, focus and technique, it became the benchmark of a skater’s ability. If you could do 10, you By Monty Little were no doubt the best on your block. Twenty to 30, the best in the town. Then there’s that elite group who can spin over 100, who are continually raising the bar, striving to be the very best. Vic Ilg, of Winnipeg, Manitoba, comes to mind. Vic spun 112 consecutive 360s at the EXPO 86 TransWorld Skateboard Championships. Then there’s Richy Carrasco from Garden Grove, California, who holds the Guinness World Record for “The most number of continuous 360 degree revolutions on a skateboard” – 142 spins, set on August 11, 2000. I know that seems unattainable, and yet the unofficial world record is 163, set way back in 1978 by Russ Howell. Is there another skater out there who will join this elite group, and perhaps even set a new record, having their name immortalized by Guinness? Now in its 62nd year of publication, Guinness World Records (formerly the Guinness Book of Records, and called the Guinness Book of World Records in the U.S.) holds a world record itself, as the best-selling copyrighted book of all time. (It’s also the most frequently stolen book from public libraries in the United States.) More than 1,000 skateboarding world records have been set over the years, from the laughable Otto the Bulldog, who recently set the record for the longest human tunnel traveled through by a dog on a skateboard, to Danny Way’s breathtaking Highest Air record, flying more than 25 feet above a quarterpipe lip. -

Resource Guide 4

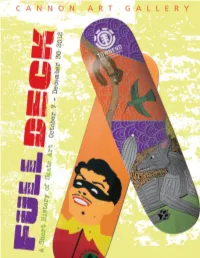

WILLIAM D. CANNON AR T G A L L E R Y TABLE OF CONTENTS Steps of the Three-Part-Art Gallery Education Program 3 How to Use This Resource Guide 4 Making the Most of Your Gallery Visit 5 The Artful Thinking Program 7 Curriculum Connections 8 About the Exhibition 10 About Street Skateboarding 11 Artist Bios 13 Pre-visit activities 33 Lesson One: Emphasizing Color 34 Post-visit activities 38 Lesson Two: Get Bold with Design 39 Lesson Three: Use Text 41 Classroom Extensions 43 Glossary 44 Appendix 53 2 STEPS OF THE THREE-PART-ART GALLERY EDUCATION PROGRAM Resource Guide: Classroom teachers will use the preliminary lessons with students provided in the Pre-Visit section of the Full Deck: A Short History of Skate Art resource guide. On return from your field trip to the Cannon Art Gallery the classroom teacher will use Post-Visit Activities to reinforce learning. The guide and exhibit images were adapted from the Full Deck: A Short History of Skate Art Exhibition Guide organized by: Bedford Gallery at the Lesher Center for the Arts, Walnut Creek, California. The resource guide and images are provided free of charge to all classes with a confirmed reservation and are also available on our website at www.carlsbadca.gov/arts. Gallery Visit: At the gallery, an artist educator will help the students critically view and investigate original art works. Students will recognize the differences between viewing copies and seeing works first and learn that visiting art galleries and museums can be fun and interesting. Hands-on Art Project: An artist educator will guide the students in a hands-on art project that relates to the exhibition. -

105 September 2018

#105 September 2018 Passes on sale until 20 October 2018’ UpgradeUpgrade toto aa fullfull yearyear forfor £259£259 Unlimited use between 1.9.18 and 31.7.19 Passes on sale until 20 October 2018’ UpgradeUpgrade toto aa fullfull yearyear forfor £259£259 Unlimited use between 1.9.18 and 31.7.19 editorial Yo, Notts! I'm Tom Quigley, a Notts photographer, skateboarder and publisher of indie skate mag, Varial Magazine. I’m stoked to have lent a hand to the 'Lion crew this month, to share my passion for skateboarding alongside a handful of our many creative and talented skateboarders. This issue, we’re demonstrating why Nottingham's skate scene is one of the best in the country and a real asset to our city. Skateboarding. You mean those kids hanging around at Sneinton Market all the time? Well, most of us aren't kids anymore, and our old skate spots like Broadmarsh Banks and the Old Market Square are long gone. Yet we're still here and skating as much as we were in the seventies, eighties and nineties. Skateboarding doesn’t have an age limit, and there’s an unbiased inclusivity that comes from that. If you wander through Sneinton Market, or “HQ”, on a summer evening – or even an autumn one; we're resilient – you'll witness a community of people, #LookUpDuck of all ages and professions, hanging out together and constantly pushing each Vicky rolls back in time with the wind. other to better themselves. All because of a piece of wood and four wheels. -

Annual Report

2006 ANNUAL REPORT PAVING THE WAY TO HEALTHY COMMUNITIES Mission Statement Letter From The Founder The Tony Hawk Foundation seeks to foster lasting improvements in society, with an emphasis on supporting and Nothing slowed down in 2006. Interest in public skateparks is still empowering youth. Through special events, grants, and technical assistance, the Foundation supports recreational on the rise, and more cities than ever are stepping up to the chal- programs with a focus on the creation of public skateboard parks in low-income communities. The Foundation favors lenge of providing facilities for their youth. However, our work is far programs that clearly demonstrate that funds received will produce tangible, ongoing, positive results. from over. Unfortunately, the cities that most desperately need public skateparks are the ones that don’t have sufficient budgets. Part of Programs our job is to augment those funds, but it is more important that we provide information and ensure that parks are built right. Knowledge The primary focus of the Tony Hawk Foundation is to help facilitate the development of free, high-quality public skateparks in low-income areas by providing information is power … but funding goes a long way. and guidance on the skatepark-development process, and through financial grants. While not all skatepark projects meet our grant criteria, the Tony Hawk Foundation Over the past year, we have awarded over $340,000 to 41 communities. strives to help communities in other ways to achieve the best possible skateparks— All told, that brings us to $1.5-million and 316 grants to help build parks that will satisfy the needs of local skaters and provide them a safe, enjoyable skateparks since our inception in 2002. -

Tommy Guerrero Discipline: Music

EDUCATOR GUIDE Story Theme: Up from the Street Subject: Tommy Guerrero Discipline: Music SECTION I - OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................2 EPISODE THEME SUBJECT CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS OBJECTIVE STORY SYNOPSIS INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES EQUIPMENT NEEDED MATERIALS NEEDED INTELLIGENCES ADDRESSED SECTION II – CONTENT/CONTEXT ..................................................................................................3 CONTENT OVERVIEW THE BIG PICTURE RESOURCES – TEXTS RESOURCES – WEB SITES VIDEO RESOURCES BAY AREA FIELD TRIPS SECTION III – VOCABULARY.............................................................................................................7 SECTION IV – ENGAGING WITH SPARK .........................................................................................8 Tommy Guerrero. Still image from SPARK story, February 2004. SECTION I - OVERVIEW EPISODE THEME INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES Up from the Street To introduce and contextualize contemporary skate culture SUBJECT To provide context for the understanding of skate Tommy Guerrero culture and contemporary music To inspire students to approach contemporary GRADE RANGES culture critically K‐12 & Post‐secondary CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS EQUIPMENT NEEDED Music & Physical Education SPARK story “Tommy Guerrero” about skateboarder and musician Tommy Guerrero on OBJECTIVES VHS or DVD and related equipment To help students ‐ Computer with Internet access, navigation software, -

6101 Wilkins and Moss.Indd I 08/07/19 4:47 PM Refocus: the American Directors Series

ReFocus: The Films of Spike Jonze 6101_Wilkins and Moss.indd i 08/07/19 4:47 PM ReFocus: The American Directors Series Series Editors: Robert Singer and Gary D. Rhodes Editorial board: Kelly Basilio, Donna Campbell, Claire Perkins, Christopher Sharrett and Yannis Tzioumakis ReFocus is a series of contemporary methodological and theoretical approaches to the interdisciplinary analyses and interpretations of neglected American directors, from the once- famous to the ignored, in direct relationship to American culture—its myths, values, and historical precepts. The series ignores no director who created a historical space—either in or out of the studio system—beginning from the origins of American cinema and up to the present. These directors produced film titles that appear in university film history and genre courses across international boundaries, and their work is often seen on television or available to download or purchase, but each suffers from a form of “canon envy”; directors such as these, among other important figures in the general history of American cinema, are underrepresented in the critical dialogue, yet each has created American narratives, works of film art, that warrant attention. ReFocus brings these American film directors to a new audience of scholars and general readers of both American and Film Studies. Titles in the series include: ReFocus: The Films of Preston Sturges Edited by Jeff Jaeckle and Sarah Kozloff ReFocus: The Films of Delmer Daves Edited by Matthew Carter and Andrew Nelson ReFocus: The Films of Amy Heckerling Edited by Frances Smith and Timothy Shary ReFocus: The Films of Budd Boetticher Edited by Gary D. -

Bamcinématek Presents Skateboarding Is Not a Crime, a 24-Film Tribute to the Best of Skateboarding in Cinema, Sep 6—23

BAMcinématek presents Skateboarding is Not a Crime, a 24-film tribute to the best of skateboarding in cinema, Sep 6—23 Opens with George Gage’s 1978 Skateboard with the director in person The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Brooklyn, NY/Aug 16, 2013—From Friday, September 6 through Thursday, September 12, BAMcinématek presents Skateboarding is Not a Crime, a 24-film tribute to the best of skateboarding in cinema, from the 1960s to the present. The ultimate in counterculture coolness, skateboarding has made an irresistibly sexy subject for movies thanks to its rebel-athlete superstars, SoCal slacker fashion, and jaw-dropping jumps, ollies, tricks, and stunts. Opening the series on Friday, September 6 is George Gage’s Skateboard (1978), following a lumpish loser who comes up with an ill-advised scheme to manage an all-teen skateboarding team in order to settle his debts with his bookie. An awesomely retro ride through 70s skateboarding culture, Skateboard was written and produced by Miami Vice producer Dick Wolf and stars teen idol Leif Garrett (Alfred Hitchcock’s daughter plays his mom!) and Z-Boys great Tony Alva. Gage will appear in person for a Q&A following the screening. Two of the earliest films in the series showcase the upright technique that dominated in the 60s. Skaterdater (1965—Sep 23), Noel Black’s freewheelingly shot, dialogue-free puppy-love story (made with pre-adolescent members of Torrance, California’s Imperial Skateboard Club) is widely considered to be the first skateboard movie. Claude Jutra’s cinéma vérité lark The Devil’s Toy (1966—Sep 23), is narrated in faux-alarmist fashion, with kids whipping down the hills of Montreal, only to have their decks confiscated by the cops.