I. Race, Gender, and Asian American Sporting Identities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

INDEX COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL JJWBT370_index.inddWBT370_index.indd 175175 88/30/10/30/10 88:23:22:23:22 PMPM JJWBT370_index.inddWBT370_index.indd 176176 88/30/10/30/10 88:23:22:23:22 PMPM A Billabong, 23 Access Hollywood, 56 Birdhouse Projects Activision Blitz fi nances impacting, 80–81 900 Films advertising creation for, 96 early days of, 15–17, 77–78 Boom Boom HuckJam sponsorship by, Hawk buy-out of, 81–82 56–57 video/fi lm involvement by, 19, 87–96 (see Tony Hawk video game designed/released also 900 Films) by, 6–7, 25–26, 36–43, 56–57, Black, Jack, 108 68–69, 73, 132, 140 (see Video Black Pearl Skatepark grand opening, games for detail) 134–136 Secret Skatepark Tour support from, 140 Blink-182, 133, 161, 162 skateboard controller designed by, 41–43 Blitz Distribution Tony Hawk Foundation contributions denim clothing investment by, 77–80 from, 158 fi nances of, 78–81 Adio Tour, 130–131 Hawk Clothing involvement offer to, 24 Adoptante, Clifford, 51, 55 Hawk relinquishing shares in, 82 Agassi, Andre, 132, 162–163 legal issues for, 17–19 Anderson, Pamela, 134, 162 skate team/company support by, 77 Antinoro, Mike, 71 video/fi lm involvement of, 90 Apatow, Judd, 107 Blogs, 99–104, 106 Apple iPhone, 91, 99–102 BMX Are You Smarter Than a 5th Grader?, 157, 158 Boom Boom HuckJam inclusion of, 48, Armstrong, Lance, 103, 108, 162 49, 51, 55–56, 58–59, 67 Athens, Georgia, 142 charitable fundraisers including, 133–134, Awards 161 MTV Video Music Awards, 131–132 Froot Loops’ endorsement including, 3, 4 Nickelodeon Kids’ Choice Awards, 7, 146 product merchandising -

The Skate of the 70S, the Colorful Vision of Hugh Holland

The skate of the 70s, the colorful vision of Hugh Holland October 8, 2020 Initially invented to replace surfing when waves were scarce, skateboarding would first develop in the 1960s in California and Hawaii. But the real golden age of skateboarding came in the 1970s with the advent of urethane wheels, making the gliding feel easier and more comfortable. The development of skateboarding during this period is therefore contagious. The exploits of young pioneers Tony Alva, Stacy Peralta and Jay Adams, members of the Z-Boys, a group of skaters revolving around the Zephyr Surfshop in Venice become unmissable. The legend of the district of Dogtown and its skaters was born. In addition, the photos taken by Craig Stecyk III and Glen E. Friedman of the time will travel around the world, and will become an incredible lever for the development of skate culture. These photographs of the young people of Dogtown will make their celebrity and will mark a whole generation of skaters. However, during this same period, these two photographers were not the only ones to immortalize the exploits of the young skaters of California. In the 70s, Hugh Holland will also participate in the work of transmission and memory of this golden age of skateboarding. With an intimate and colorful vision, Holland will stand out with his one-of-a kind works. Following a major drought in 1976, skaters began to ride empty pools in Los Angeles neighborhoods, creating a new kind of skateboarding. This more vertical practice was to be the foundation of skateboarding in the 80s and 90s. -

Skating to Success: What an Afterschool Skateboard Mentoring Program Can Bring to PUSD Middle Schoolers

Skating to Success: What an Afterschool Skateboard Mentoring Program Can Bring to PUSD Middle Schoolers Zander Silverman Urban Environmental Policy Senior Comprehensive Project Professor Cha, Professor Matsuoka 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary – 2 Acknowledgements - 3 Introduction - 4 Background - 5 Literature Review - 7 Culture of Skateboarder - 7 Sexism in Skateboarding - 8 Skateboarding and Adolescent Development - 9 Public Perception of Skateboarding - 10 Skateboarding and Struggles for Urban Space - 11 Afterschool Programs - 14 Social Benefits - 14 Educational Benefits - 16 Physical/Health Benefits - 17 Methodology - 22 Research Questions - 22 Participants - 22 Materials - 22 Design and Procedure - 23 Case Study Introduction - 23 Findings - 27 Overview - 27 Benefits of Skateboarding - 28 Sexism in Skateboarding - 30 Skateboarding and Higher Education - 31 Skateboarding and After School Programs - 33 Role of After School Programs - 36 Components/Obstacles to After School Programs - 37 Attitudes Toward Skateboarding Mentoring Program - 38 Analysis - 39 Recommendations - 45 #1.Amend PUSD Policy to Remove Skateboarding from “Activities with Safety Risks” - 45 # 2: Adapt PUSD Policy on Community Partnerships to a Skateboard Mentoring Program - 46 # 3. Remove Skateboarding From Prohibited Activities at Occidental College - 47 #4. Expand the Skateboard Industry’s Support to NGO’s -48 #5. Expand Availability of Certification Methods for Skateboard Programmers - 49 Conclusion - 51 Appendix # 1: Full List of Interviewees and Titles – 53 Appendix # 2: PUSD Policy AR 1330.1 Joint Use Agreements - 54 Appendix # 3: SBA Australia Certification Process – 55 Bibliography - 56 2 Executive Summary The following report discusses the potential of an afterschool skateboard mentoring program that pairs college students with middle schoolers in Pasadena Unified School District (PUSD). -

Masaryk University Brno

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English language and literature The origin and development of skateboarding subculture Bachelor thesis Brno 2017 Supervisor: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. author: Jakub Mahdal Bibliography Mahdal, Jakub. The origin and development of skateboarding subculture; bachelor thesis. Brno; Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, Department of English Language and Literature, 2017. NUMBER OF PAGES. The supervisor of the Bachelor thesis: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. Bibliografický záznam Mahdal, Jakub. The origin and development of skateboarding subculture; bakalářská práce. Brno; Masarykova univerzita, Pedagogická fakulta, Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury, 2017. POČET STRAN. Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. Abstract This thesis analyzes the origin and development of skateboarding subculture which emerged in California in the fifties. The thesis is divided into two parts – a theoretical part and a practical part. The theoretical part introduces the definition of a subculture, its features and functions. This part further describes American society in the fifties which provided preconditions for the emergence of new subcultures. The practical part analyzes the origin and development of skateboarding subculture which was influenced by changes in American mass culture. The end of the practical part includes an interconnection between the values of American society and skateboarders. Anotace Tato práce analyzuje vznik a vývoj skateboardové subkultury, která vznikla v padesátých letech v Kalifornii. Práce je rozdělena do dvou částí – teoretické a praktické. Teoretická část představuje pojem subkultura, její rysy a funkce. Tato část také popisuje Americkou společnost v 50. letech, jež poskytla podmínky pro vznik nových subkultur. -

Individual and Community Culture at the Notorious Burnside Skatcpark Hames Ellerbe Universi

Socially Infamous Socially Infamous: Individual and Community Culture at the Notorious Burnside Skatcpark Hames Ellerbe University of Oregon A master's research project Presented to the Arts and Administration Program of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Arts Administration Socially Infamous iii Approved by: Arts and Administration Program University of Oregon Socially Infamous V Abstract and Key Words Ahslracl This research project involves sociocultural validation of the founding members and early participants of Burnside Skatepark. The group developed socioculturally through the creation and use of an internationally renowned Do fl Yourse{l(DIY) skatepark. Located under the east side of the Burnside Bridge in Portland, Oregon and founded in 1990, Burnside Skatepark is one of the most famous skateparks in the world, infamous for territorialism, attitude, and difficulty. On the other hand, the park has been built with dedication, devoid ofcity funding and approval, in an area known, in the earlier days of the park, as a crime infested, former industrial district. Through the do ii yourselfcreation of Burnside skatepark, came the sociocultural cultivation and development of the founding participants and skaters. Additionally, the creation of the park provided substantial influence in the sociocultural development of a number of professional skateboarders and influenced the creation of parks worldwide. By identifying the sociocultural development and cultivation of those involved with the Burnside skatepark, specifically two of the founders, and one professional skateboarder, consideration can be provided into how skateboarding, creating a space, and skate participation may lead to significant development of community, social integrity, and self-worth even in the face of substantial gentrification. -

By Monty Little Were No Doubt the Best on Your Block

efore the days of the ollie, you measured the skill level of a skateboarder by how many 360s he (or she) could do. As Bspinning required balance, power, focus and technique, it became the benchmark of a skater’s ability. If you could do 10, you By Monty Little were no doubt the best on your block. Twenty to 30, the best in the town. Then there’s that elite group who can spin over 100, who are continually raising the bar, striving to be the very best. Vic Ilg, of Winnipeg, Manitoba, comes to mind. Vic spun 112 consecutive 360s at the EXPO 86 TransWorld Skateboard Championships. Then there’s Richy Carrasco from Garden Grove, California, who holds the Guinness World Record for “The most number of continuous 360 degree revolutions on a skateboard” – 142 spins, set on August 11, 2000. I know that seems unattainable, and yet the unofficial world record is 163, set way back in 1978 by Russ Howell. Is there another skater out there who will join this elite group, and perhaps even set a new record, having their name immortalized by Guinness? Now in its 62nd year of publication, Guinness World Records (formerly the Guinness Book of Records, and called the Guinness Book of World Records in the U.S.) holds a world record itself, as the best-selling copyrighted book of all time. (It’s also the most frequently stolen book from public libraries in the United States.) More than 1,000 skateboarding world records have been set over the years, from the laughable Otto the Bulldog, who recently set the record for the longest human tunnel traveled through by a dog on a skateboard, to Danny Way’s breathtaking Highest Air record, flying more than 25 feet above a quarterpipe lip. -

Resource Guide 4

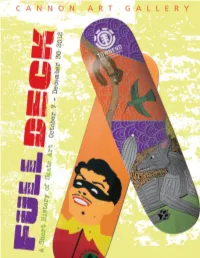

WILLIAM D. CANNON AR T G A L L E R Y TABLE OF CONTENTS Steps of the Three-Part-Art Gallery Education Program 3 How to Use This Resource Guide 4 Making the Most of Your Gallery Visit 5 The Artful Thinking Program 7 Curriculum Connections 8 About the Exhibition 10 About Street Skateboarding 11 Artist Bios 13 Pre-visit activities 33 Lesson One: Emphasizing Color 34 Post-visit activities 38 Lesson Two: Get Bold with Design 39 Lesson Three: Use Text 41 Classroom Extensions 43 Glossary 44 Appendix 53 2 STEPS OF THE THREE-PART-ART GALLERY EDUCATION PROGRAM Resource Guide: Classroom teachers will use the preliminary lessons with students provided in the Pre-Visit section of the Full Deck: A Short History of Skate Art resource guide. On return from your field trip to the Cannon Art Gallery the classroom teacher will use Post-Visit Activities to reinforce learning. The guide and exhibit images were adapted from the Full Deck: A Short History of Skate Art Exhibition Guide organized by: Bedford Gallery at the Lesher Center for the Arts, Walnut Creek, California. The resource guide and images are provided free of charge to all classes with a confirmed reservation and are also available on our website at www.carlsbadca.gov/arts. Gallery Visit: At the gallery, an artist educator will help the students critically view and investigate original art works. Students will recognize the differences between viewing copies and seeing works first and learn that visiting art galleries and museums can be fun and interesting. Hands-on Art Project: An artist educator will guide the students in a hands-on art project that relates to the exhibition. -

Tommy Guerrero Discipline: Music

EDUCATOR GUIDE Story Theme: Up from the Street Subject: Tommy Guerrero Discipline: Music SECTION I - OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................2 EPISODE THEME SUBJECT CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS OBJECTIVE STORY SYNOPSIS INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES EQUIPMENT NEEDED MATERIALS NEEDED INTELLIGENCES ADDRESSED SECTION II – CONTENT/CONTEXT ..................................................................................................3 CONTENT OVERVIEW THE BIG PICTURE RESOURCES – TEXTS RESOURCES – WEB SITES VIDEO RESOURCES BAY AREA FIELD TRIPS SECTION III – VOCABULARY.............................................................................................................7 SECTION IV – ENGAGING WITH SPARK .........................................................................................8 Tommy Guerrero. Still image from SPARK story, February 2004. SECTION I - OVERVIEW EPISODE THEME INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES Up from the Street To introduce and contextualize contemporary skate culture SUBJECT To provide context for the understanding of skate Tommy Guerrero culture and contemporary music To inspire students to approach contemporary GRADE RANGES culture critically K‐12 & Post‐secondary CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS EQUIPMENT NEEDED Music & Physical Education SPARK story “Tommy Guerrero” about skateboarder and musician Tommy Guerrero on OBJECTIVES VHS or DVD and related equipment To help students ‐ Computer with Internet access, navigation software, -

Jeff Ho Surfboards and Zephyr Productions Opened in 1973 and Closed in 1976

Sharp Sans Display No.2 Designed By Lucas Sharp In 2015 Available In 20 Styles, Licenses For Web, Desktop & App 1 All Caps Roman POWELLPERALTA Black — 50pt BANZAI PIPELINE Extrabold — 50pt BALI INDONESIA Bold — 50pt MICKEY MUÑOZ Semibold — 50pt TSUNAMI WAVE Medium — 50pt MALIA MANUEL Book — 50pt MIKE STEWART Light — 50pt WESTWAYS CA Thin — 50pt TYLER WRIGHT Ultrathin — 50pt FREIDA ZAMBA Hairline — 50pt Sharp Sans Display No.2 2 All Caps Oblique ROBERT WEAVER Black oblique — 50pt DENNIS HARNEY Extrabold oblique — 50pt PAUL HOFFMAN Bold oblique — 50pt NATHAN PRATT Semibold oblique — 50pt BOB SIMMONS Medium oblique — 50pt MIKE PARSONS Book oblique — 50pt JAMIE O'BRIEN Light oblique — 50pt JACK LONDON Thin oblique — 50pt KAVE KALAMA Ultrathin oblique — 50pt CRAIG STECYK Hairline oblique — 50pt Sharp Sans Display No.2 3 All Caps Roman Lubalin Ligatures JOYCE HOFFMAN Black (Lubalin Ligatures) — 50pt FRED HEMMINGS Extrabold (Lubalin Ligatures) — 50pt MATADOR BEACH Bold (Lubalin Ligatures) — 50pt OAHU WAVE INT. Semibold (Lubalin Ligatures) — 50pt DREW KAMPION Medium (Lubalin Ligatures) — 50pt ROB MACHADO Book (Lubalin Ligatures) — 50pt HEATHER CLARK Light (Lubalin Ligatures) — 50pt PAPAKOLEA BAY Thin (Lubalin Ligatures) — 50pt MIKE PARSONS Ultrathin (Lubalin Ligatures ) — 50pt LAIRD HAMILTON Hairline (Lubalin Ligatures) — 50pt Sharp Sans Display No.2 4 Title Case Roman Hawaii Five-O Black — 50pt Playa Del Rey Extrabold — 50pt Fuerteventura Bold oblique — 50pt Sunny Garcia Semibold — 50pt Zephyr Team Medium — 50pt The Dogbowl Book — 50pt Pismo -

Skate Parks: a Guide for Landscape Architects and Planners

SKATE PARKS: A GUIDE FOR LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS AND PLANNERS by DESMOND POIRIER B.F.A., Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Rhode Island, 1999. A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE Department of Landscape Architecture College of Regional and Community Planning KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2008 Approved by: Major Professor Stephanie A. Rolley, FASLA, AICP Copyright DESMOND POIRIER 2008 Abstract Much like designing golf courses, designing and building skateboard parks requires very specific knowledge. This knowledge is difficult to obtain without firsthand experience of the sport in question. An understanding of how design details such as alignment, layout, surface, proportion, and radii of the curved surfaces impact the skateboarder’s experience is essential and, without it, a poor park will result. Skateboarding is the fastest growing sport in the US, and new skate parks are being fin- ished at a rate of about three per day. Cities and even small towns all across North America are committing themselves to embracing this sport and giving both younger and older participants a positive environment in which to enjoy it. In the interest of both the skateboarders who use them and the people that pay to have them built, it is imperative that these skate parks are built cor- rectly. Landscape architects will increasingly be called upon to help build these public parks in conjunction with skate park design/builders. At present, the relationship between landscape architects and skate park design/builders is often strained due to the gaps in knowledge between the two professions. -

Skate Life: Re-Imagining White Masculinity by Emily Chivers Yochim

/A7J;(?<; technologies of the imagination new media in everyday life Ellen Seiter and Mimi Ito, Series Editors This book series showcases the best ethnographic research today on engagement with digital and convergent media. Taking up in-depth portraits of different aspects of living and growing up in a media-saturated era, the series takes an innovative approach to the genre of the ethnographic monograph. Through detailed case studies, the books explore practices at the forefront of media change through vivid description analyzed in relation to social, cultural, and historical context. New media practice is embedded in the routines, rituals, and institutions—both public and domestic—of everyday life. The books portray both average and exceptional practices but all grounded in a descriptive frame that ren- ders even exotic practices understandable. Rather than taking media content or technol- ogy as determining, the books focus on the productive dimensions of everyday media practice, particularly of children and youth. The emphasis is on how specific communities make meanings in their engagement with convergent media in the context of everyday life, focusing on how media is a site of agency rather than passivity. This ethnographic approach means that the subject matter is accessible and engaging for a curious layperson, as well as providing rich empirical material for an interdisciplinary scholarly community examining new media. Ellen Seiter is Professor of Critical Studies and Stephen K. Nenno Chair in Television Studies, School of Cinematic Arts, University of Southern California. Her many publi- cations include The Internet Playground: Children’s Access, Entertainment, and Mis- Education; Television and New Media Audiences; and Sold Separately: Children and Parents in Consumer Culture. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 3, 2019 San Francisco, CA 42Nd Annual Haight-Ashbury Street Fair Announces 2019 Line-Up - Sponsored by COOKIES

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 3, 2019 San Francisco, CA 42nd Annual Haight-Ashbury Street Fair Announces 2019 Line-Up - sponsored by COOKIES. The Haight-Ashbury Street Fair is a non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the cultural and historical significance of this district by sponsoring the annual community celebration and in supporting community programs that incorporate the neighborhood’s spirit of diversity, cooperation and humanism. Donate here to keep the tradition going! Since 1978, we have produced the annual, one-day street fair that allows the community to celebrate the cultural contributions this district has made to San Francisco. This festival provides the neighborhood with the opportunity to showcase the variety of mercantile, cultural and community services available in this district. By creating a festival atmosphere, the street fair creates a stage for many artisans, musicians, artists and performers to present their work to the public. And, as a community service, HASF enables many non-profit organizations a chance to conduct outreach campaigns. Our activities are not limited to a one-day festival. We also sponsor other community events such as the annual Halloween Hootenanny that provides a safe environment for the children of the neighborhood to celebrate the spirit of Halloween. We hope (intend) to promote and create many more programs and events that help serve the cultural needs of the Haight-Ashbury and anyone else that would like to join in on the fun. The 42nd Annual Haight Street Festival takes place Sunday, June 09, 2019, 11 - 5:30 pm. The 2019 Lineup has brought in veteran Edward Jennings of Haight Street’s historic i-Beam to curate an unforgettable line-up with collaborations and surprise guest appearances not to be missed.