EAHN Book of Abstracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Catalog 12-14.Pdf

www.legionpaper.com www.moabpaper.com www.risingmuseumboard.com www.solvart.com © Copyright 2019 Legion Paper Corporation All Rights Reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced without the permission of Legion Paper. OUR ROMANCE WITH PAPER Peace treaties are signed on it. Declarations of love are written on it. Artists’ works are portrayed on it. Of course, we mean paper; the medium that has evolved to reflect its own poetry, becoming an opportunity for pure innovation and unlimited creativity. Through the years, a melding of ancient craft and enlightened technology occurred, creating new practices and opening new horizons for expression in paper. When we trace its history, we find insight into man’s relentless imagination and creativity. Today, this convergence of ancient and modern continues and paper emerges with not only greater variety but a renewed appreciation of quality. To some, fine paper is the space that translates what is conceived in the mind to what is authentic. To others, having access to the right paper represents abundant possibility and profitability. The very selection of paper now becomes an adventure, realizing how the end result will vary based upon choice. Today, as in the years past, Legion Paper continues to source the finest papermakers around the globe, respecting the skill of the artisan and the unique attributes of the finished product. As we head into the future, Legion remains steadfast in its commitment to diversity, customer service and an unparalleled level of professionalism. We’re sure you will want to touch and feel some of the 3,500 papers described on the following pages. -

C:\Data\WP\F\200\Catalogue Sections\Aaapreliminary Pages.Wpd

Jonathan A. Hill, Bookseller, Inc. 325 West End Avenue, Apt. 10B New York City, New York, 10023-8145 Tel: 646 827-0724 Fax: 212 496-9182 E-mail: [email protected] Catalogue 200 Proofs Science, Medicine, Natural History, Bibliography, & Much More Introduction & Selective Subject Index on Following Pages Introduction TWO HUNDRED CATALOGUES in thirty-three years: more than 35,000 books and manuscripts have been described in these catalogues. Thousands of other books, including many of the most important and unusual, never found their way into my catalogues, having been quickly sold before their descriptions could appear in print. In the last fifteen years, since my Catalogue 100 appeared, many truly exceptional books passed through my hands. Of these, I would like to mention three. The first, sold in 2003 was a copy of the first edition in Latin of the Columbus Letter of 1493. This is now in a private collection. In 2004, I was offered a book which I scarcely dreamed of owning: the Narratio Prima of Rheticus, printed in 1540. Presenting the first announcement of the heliocentric system of Copernicus, this copy in now in the Linda Hall Library in Kansas City, Missouri. Both of the books were sold before they could appear in my catalogues. Finally, the third book is an absolutely miraculous uncut copy in the original limp board wallet binding of Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius of 1610. Appearing in my Catalogue 178, this copy was acquired by the Library of Congress. This is the first and, probably the last, “personal” catalogue I will prepare. -

Preferred Source Application Requests

PREFERRED SOURCE APPLICATIONS APPROVED BY OGS AUGUST 2010 THROUGH OCTOBER 2010 Total Total OGS PSG Direct Disabled/ ESD Request Annual Sales Labor Blind Approval Control Number Commodity Type Customer Volume Workshop FTE's FTE's Date 823 Personal Protection Spray New Statewide $40,398.00 Herkimer Area ARC .07 .07 8/23/10 828 HIV Rapid Test Kits New Statewide $200,000.00 Maryhaven Center of Hope .447 .383 8/5/10 Diesel Exhaust Fluid 832 275 and 330 gallon tote New Statewide $200,000.00 Liberty Enterprises Inc .2345 .1759 9/29/10 Diesel Exhaust Fluid 833 55 gallon drum New Statewide $30,000.00 Liberty Enterprises Inc .1614 .1210 9/29/10 835 Thermal Paper Rolls New Statewide $84,000.00 ARC Oneida Lewis .1097 .1036 10/8/10 Description for My®Clyns Personal Protection Spray My®Clyns Personal Protection Spray represents a new category of product that is intended to be used following exposure to bodily fluids or other materials potentially containing harmful pathogens. It is the only non-alcohol option you can keep in your pocket and spray directly into your face, eyes, ears, nose, mouth and open wounds. It is ready to use in the field when you need effective protection right away. This commodity is provided by Herkimer Area ARC and will be available to all State Agencies. Work for the disabled includes receiving packaging, removing individual units and transferring to an assembly line, assemble shipping box, fill box with 12 units, close box and tape shut, apply shipping label and load pallet with finished product. -

Title Historical Value of Parabaik and Pei All Authors Moe Moe Oo Publication Type Local Publication Publisher (Journal Name, Is

Title Historical Value of Parabaik and Pei All Authors Moe Moe Oo Publication Type Local Publication Publisher (Journal name, Meiktila University, Research Journal, Vol.IV, No.1, 2013 issue no., page no etc.) Parabaiks and Palm Leaf Manuscripts are important in the rich and old tradition and cultural history of Southeast Asia. Many documents reflected the socio- economic situation and Buddhist text of ancient Myanmar. These sources are Abstract like a treasure-trove for historians. We hope that this Parabaik and Palm leaf will advance the study of the early modern history of Myanmar, as well as that of the whole Southeast Asian region, and will also contribute to the preservation of a valuable cultural heritage in Myanmar. cultural heritage, preservation Keywords Citation Issue Date 2013 61 Meiktila University, Research Journal, Vol.IV, No.1, 2013 Historical Value of Parabaik and Pei Moe Moe Oo1 Abstract Parabaiks and Palm Leaf Manuscripts are important in the rich and old tradition and cultural history of Southeast Asia. Many documents reflected the socio-economic situation and Buddhist text of ancient Myanmar. These sources are like a treasure-trove for historians. We hope that this Parabaik and Palm leaf will advance the study of the early modern history of Myanmar, as well as that of the whole Southeast Asian region, and will also contribute to the preservation of a valuable cultural heritage in Myanmar. Key Words: cultural heritage, preservation Introduction Myanmar Manuscripts are an attempt to deal with the socio- economic life of the people during the Kon-baung period. There are many books both published and unpublished in the forms of research journal and thesis. -

'Quilled on the Cann': Alexander Hart, Scottish Cabinet Maker, Radical

‘QUILLED ON THE CANN’ ALEXANDER HART, SCOTTISH CABINET MAKER, RADICAL AND CONVICT John Hawkins A British Government at war with Revolutionary and Republican France was fully aware of the dangers of civil unrest amongst the working classes in Scotland for Thomas Paine’s Republican tract The Rights of Man was widely read by a particularly literate artisan class. The convict settlement at Botany Bay had already been the recipient of three ‘Scottish martyrs’, the Reverend Thomas Palmer, William Skirving and Thomas Muir, tried in 1793 for seeking an independent Scottish republic or democracy, thereby forcing the Scottish Radical movement underground. The onset of the Industrial Revolution, and the conclusion of the Napoleonic wars placed the Scottish weavers, the so called ‘aristocrats’ of labour, in a difficult position for as demand for cloth slumped their wages plummeted. As a result, the year 1819 saw a series of Radical protest meetings in west and central Scotland, where many thousands obeyed the order for a general strike, the first incidence of mass industrial action in Britain. The British Government employed spies to infiltrate these organisations, and British troops were aware of a Radical armed uprising under Andrew Hardie, a Glasgow weaver, who led a group of twenty five Radicals armed with pikes in the direction of the Carron ironworks, in the hope of gaining converts and more powerful weapons. They were joined at Condorrat by another group under John Baird, also a weaver, only to be intercepted at Bonnemuir, where after a fight twenty one Radicals were arrested and imprisoned in Stirling Castle. -

'Paper Houses'

‘Paper houses’ John Macarthur and the 30-year design process of Camden Park Volume 2: appendices Scott Ethan Hill A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Faculty of Architecture, Design and Planning, University of Sydney Sydney, Australia 10th August, 2016 (c) Scott Hill. All rights reserved Appendices 1 Bibliography 2 2 Catalogue of architectural drawings in the Mitchell Library 20 (Macarthur Papers) and the Camden Park archive Notes as to the contents of the papers, their dating, and a revised catalogue created for this dissertation. 3 A Macarthur design and building chronology: 1790 – 1835 146 4 A House in Turmoil: Just who slept where at Elizabeth Farm? 170 A resource document drawn from the primary sources 1826 – 1834 5 ‘Small town boy’: An expanded biographical study of the early 181 life and career of Henry Kitchen prior to his employment by John Macarthur. 6 The last will and testament of Henry Kitchen Snr, 1804 223 7 The last will and testament of Mary Kitchen, 1816 235 8 “Notwithstanding the bad times…”: An expanded biographical 242 study of Henry Cooper’s career after 1827, his departure from the colony and reported death. 9 The ledger of John Verge: 1830-1842: sections related to the 261 Macarthurs transcribed from the ledger held in the Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, A 3045. 1 1 Bibliography A ACKERMANN, JAMES (1990), The villa: form and ideology of country houses. London, Thames & Hudson. ADAMS, GEORGE (1803), Geometrical and Graphical Essays Containing a General Description of the of the mathematical instruments used in geometry, civil and military surveying, levelling, and perspective; the fourth edition, corrected and enlarged by William Jones, F. -

AH374 Australian Art and Architecture

AH374 Australian Art and Architecture The search for beauty, meaning and freedom in a harsh climate Boston University Sydney Centre Spring Semester 2015 Course Co-ordinator Peter Barnes [email protected] 0407 883 332 Course Description The course provides an introduction to the history of art and architectural practice in Australia. Australia is home to the world’s oldest continuing art tradition (indigenous Australian art) and one of the youngest national art traditions (encompassing Colonial art, modern art and the art of today). This rich and diverse history is full of fascinating characters and hard won aesthetic achievements. The lecture series is structured to introduce a number of key artists and their work, to place them in a historical context and to consider a range of themes (landscape, urbanism, abstraction, the noble savage, modernism, etc.) and issues (gender, power, freedom, identity, sexuality, autonomy, place etc.) prompted by the work. Course Format The course combines in-class lectures employing a variety of media with group discussions and a number of field trips. The aim is to provide students with a general understanding of a series of major achievements in Australian art and its social and geographic context. Students should also gain the skills and confidence to observe, describe and discuss works of art. Course Outline Week 1 Session 1 Introduction to Course Introduction to Topic a. Artists – The Port Jackson Painter, Joseph Lycett, Tommy McCrae, John Glover, Augustus Earle, Sydney Parkinson, Conrad Martens b. Readings – both readers are important short texts. It is compulsory to read them. They will be discussed in class and you will need to be prepared to contribute your thoughts and opinions. -

Handmade Gampi

Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................ 2 About Us & Ordering Terms ............................................ 3 History of Washi ................................................................ 4 Japanese Papermaking .................................................... 5 Differences Between Washi and Western Paper ................... 7 Where our Washi Comes From ...................................... 8 Paper Specifications ........................................................ 11 Pricelist ............................................................................... 16 Fine Art and Conservation Handmade Papers ............................................. 20 Machinemade Papers ....................................... 26 Gampi Papers ..................................................... 29 Large Size Papers .............................................. 31 Small Size/ Specialty Papers .......................... 34 Rolls 100% Kozo Rolls ................................................ 36 Kozo Mix Rolls ................................................... 38 100% Sulphite Pulp Rolls ................................. 38 Inkjet Coated Rolls ........................................... 39 Gampi Rolls ........................................................ 39 Rayon Rolls ......................................................... 40 Decorative Rolls ................................................ 40 Decorative ........................................................................ -

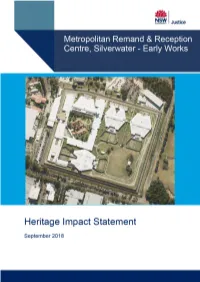

Silverwater Correctional Complex Upgrade Early Works

THIS PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK Table of Contents Contents Heritage Impact Statement ........................................................................................................... 1 Document Control .................................................................................................................... 5 1. Project Overview ............................................................................................................. 6 1.1 Background .......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 The Site ................................................................................................................................ 7 1.3 Heritage Context ................................................................................................................... 8 1.4 Silverwater Correctional Complex CMP ................................................................................ 8 2. History ............................................................................................................................ 10 3. Site and Building Descriptions ..................................................................................... 13 3.1 Context within the Site ........................................................................................................ 13 3.2 Current Use ........................................................................................................................ 13 4. Significance -

The Journal of the Walters Art Museum

THE JOURNAL OF THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM VOL. 73, 2018 THE JOURNAL OF THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM VOL. 73, 2018 EDITORIAL BOARD FORM OF MANUSCRIPT Eleanor Hughes, Executive Editor All manuscripts must be typed and double-spaced (including quotations and Charles Dibble, Associate Editor endnotes). Contributors are encouraged to send manuscripts electronically; Amanda Kodeck please check with the editor/manager of curatorial publications as to compat- Amy Landau ibility of systems and fonts if you are using non-Western characters. Include on Julie Lauffenburger a separate sheet your name, home and business addresses, telephone, and email. All manuscripts should include a brief abstract (not to exceed 100 words). Manuscripts should also include a list of captions for all illustrations and a separate list of photo credits. VOLUME EDITOR Amy Landau FORM OF CITATION Monographs: Initial(s) and last name of author, followed by comma; italicized or DESIGNER underscored title of monograph; title of series (if needed, not italicized); volume Jennifer Corr Paulson numbers in arabic numerals (omitting “vol.”); place and date of publication enclosed in parentheses, followed by comma; page numbers (inclusive, not f. or ff.), without p. or pp. © 2018 Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery, 600 North Charles Street, Baltimore, L. H. Corcoran, Portrait Mummies from Roman Egypt (I–IV Centuries), Maryland 21201 Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 56 (Chicago, 1995), 97–99. Periodicals: Initial(s) and last name of author, followed by comma; title in All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the written double quotation marks, followed by comma, full title of periodical italicized permission of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland. -

Stag Bijvoet in Paris

BIJVOET IN FRANCE 1925–1945 Sanatorium Zonnestraal, under construction, Hilversum B. Bijvoet, J. Duiker, 1927–1931 picture by J.D. Honings introduction ‘From 1926 until after the war Bijvoet, who for years now has lived and worked in Haarlem, spent most of his time in France, although he still got commissions from the Netherlands (one was for the Gooiland Hotel in Hilversum). In Paris it was interior design that received his care and attention. During those years he designed, in collaboration with Pierre Chareau, numerous costly conversions and interiors of prominent Paris apartments.’1 contacts There is no way of finding out whom Bijvoet consorted with in Paris, as there are virtually no sources to draw on. We do know that he worked with Chareau and Beaudouin & Lods, that he lived for several of the war years in the Dordogne with Marcel Lods, András Szivessy (André Sive) and Vladimir Bodiansky and that he was in touch with Le Corbusier (according to a letter to the Andriessens). He must have been influenced by each of them. From this you might contend that the curved wall of the golf club house in Beauvallon, which Bijvoet designed early on in his association with Chareau, derives from the one in the salon of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret’s Maison La Roche (1923–1925). Maybe the round columns do too. A new departure for Bijvoet at the time, from then on he would scarcely use anything else. It also makes sense to compare their Villa Vent d’Aval, located near the golf club and completed by André Barbier-Bouvet after the war, with Le Corbusier’s Maison Cook (1926). -

08 November 1980, No 4

THE AUSTRALIANA SOCIETY NEWSLETTER 1980/4 November 1980 y ^^M MM mm •SHI THE AUSTRALIANA SOCIETY NEWSLETTER ISSN 0156.8019 The Australiana Society P.O. Box A 378 Sydney South NSW 2000 1980A November 1980 EDITORIAL: Museums and the Collector p.4 SOCIETY INFORMATION p.5 AUSTRALIANA NEWS p.6 AUSTRALIANA EXHIBITIONS p.10 OUR AUTHORS p.12 ARTICLES - Richard Phillips: The Bosleyware Pottery p.13 Michel Reymond: Land Records and Historic Buildings p.16 Ian Evans: A Portrait of Mrs. John Verge p.17 ANNUAL REPORT p.19 AUSTRALIANA BOOKS p.21 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS p.15 MEMBERSHIP FORM p.26 Registered for posting as a publication - category B Copyright 1980 The Australiana Society. All material written or illustrative, credited to an author, is copyright We gratefully record our thanks to James R. Lawson Pty. Ltd. for their generous donation which allows us to provide the photographs on the cover. production - aZhoJvt fie,yu>km (02) SU 1846 h Editorial MUSEUMS AND THE COLLECTOR "The editor cannot help concluding with a wish that the nobility and gentry would condescend to make their cabinets and collections accessible to the curious as is consistent with their safety." Thomas Martyn, 1766. Two hundred years after these words were written, economic pressures compelled the British aristocracy to open the doors of the great houses to the curious public. Today in Australia, while private collections are frequently available to the public through National Trust open days, exhibitions in public museums, or other means, the public collections of museums are all too rarely accessible. Museums draw too hard a line between those things which the public may see - the things on display - and those things the public may not see - the things in "storage".