The Unintentional Misidentification of a Psychoactive Species from Fiji by R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

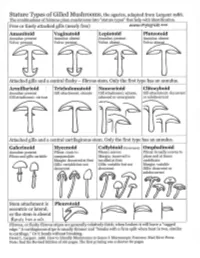

Agarics-Stature-Types.Pdf

Gilled Mushroom Genera of Chicago Region, by stature type and spore print color. Patrick Leacock – June 2016 Pale spores = white, buff, cream, pale green to Pinkish spores Brown spores = orange, Dark spores = dark olive, pale lilac, pale pink, yellow to pale = salmon, yellowish brown, rust purplish brown, orange pinkish brown brown, cinnamon, clay chocolate brown, Stature Type brown smoky, black Amanitoid Amanita [Agaricus] Vaginatoid Amanita Volvariella, [Agaricus, Coprinus+] Volvopluteus Lepiotoid Amanita, Lepiota+, Limacella Agaricus, Coprinus+ Pluteotoid [Amanita, Lepiota+] Limacella Pluteus, Bolbitius [Agaricus], Coprinus+ [Volvariella] Armillarioid [Amanita], Armillaria, Hygrophorus, Limacella, Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Coprinus+, Hypholoma, Neolentinus, Pleurotus, Tricholoma Cyclocybe, Gymnopilus Lacrymaria, Stropharia Hebeloma, Hemipholiota, Hemistropharia, Inocybe, Pholiota Tricholomatoid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Laccaria, Lactarius, Entoloma Cortinarius, Hebeloma, Lyophyllum, Megacollybia, Melanoleuca, Inocybe, Pholiota Russula, Tricholoma, Tricholomopsis Naucorioid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Hypsizygus, Laccaria, Entoloma Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Hypholoma Lactarius, Rhodocollybia, Rugosomyces, Hebeloma, Gymnopilus, Russula, Tricholoma Pholiota, Simocybe Clitocyboid Ampulloclitocybe, Armillaria, Cantharellus, Clitopilus Paxillus, [Pholiota], Clitocybe, Hygrophoropsis, Hygrophorus, Phylloporus, Tapinella Laccaria, Lactarius, Lactifluus, Lentinus, Leucopaxillus, Lyophyllum, Omphalotus, Panus, Russula Galerinoid Galerina, Pholiotina, Coprinus+, -

The Good, the Bad and the Tasty: the Many Roles of Mushrooms

available online at www.studiesinmycology.org STUDIES IN MYCOLOGY 85: 125–157. The good, the bad and the tasty: The many roles of mushrooms K.M.J. de Mattos-Shipley1,2, K.L. Ford1, F. Alberti1,3, A.M. Banks1,4, A.M. Bailey1, and G.D. Foster1* 1School of Biological Sciences, Life Sciences Building, University of Bristol, 24 Tyndall Avenue, Bristol, BS8 1TQ, UK; 2School of Chemistry, University of Bristol, Cantock's Close, Bristol, BS8 1TS, UK; 3School of Life Sciences and Department of Chemistry, University of Warwick, Gibbet Hill Road, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK; 4School of Biology, Devonshire Building, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 7RU, UK *Correspondence: G.D. Foster, [email protected] Abstract: Fungi are often inconspicuous in nature and this means it is all too easy to overlook their importance. Often referred to as the “Forgotten Kingdom”, fungi are key components of life on this planet. The phylum Basidiomycota, considered to contain the most complex and evolutionarily advanced members of this Kingdom, includes some of the most iconic fungal species such as the gilled mushrooms, puffballs and bracket fungi. Basidiomycetes inhabit a wide range of ecological niches, carrying out vital ecosystem roles, particularly in carbon cycling and as symbiotic partners with a range of other organisms. Specifically in the context of human use, the basidiomycetes are a highly valuable food source and are increasingly medicinally important. In this review, seven main categories, or ‘roles’, for basidiomycetes have been suggested by the authors: as model species, edible species, toxic species, medicinal basidiomycetes, symbionts, decomposers and pathogens, and two species have been chosen as representatives of each category. -

Morphological Description and New Record of Panaeolus Acuminatus (Agaricales) in Brazil

Studies in Fungi 4(1): 135–141 (2019) www.studiesinfungi.org ISSN 2465-4973 Article Doi 10.5943/sif/4/1/16 Morphological description and new record of Panaeolus acuminatus (Agaricales) in Brazil Xavier MD1, Silva-Filho AGS2, Baseia IG3 and Wartchow F4 1 Curso de Graduação em Ciências Biológicas, Centro de Biociências, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Av. Senador Salgado Filho, 3000, Campus Universitário, 59072-970, Natal, RN, Brazil 2 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sistemática e Evolução, Centro de Biociências, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Av. Senador Salgado Filho, 3000, Campus Universitário, 59072-970, Natal, RN, Brazil 3 Departamento de Botânica e Zoologia, Centro de Biociências, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Av. Senador Salgado Filho, 3000, Campus Universitário, 59072-970, Natal, RN, Brazil 4 Departamento de Sistemática e Ecologia, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Conj. Pres. Castelo Branco III, 58033- 455, João Pessoa, PB, Brazil Xavier MD, Silva-Filho AGS, Baseia IG, Wartchow F 2019 – Morphological description and new record of Panaeolus acuminatus (Agaricales) in Brazil. Studies in Fungi 4(1), 135–141, Doi 10.5943/sif/4/1/16 Abstract Panaeolus acuminatus is described and illustrated based on fresh specimens collected from Northeast Brazil. This is the second known report of this species for the country, since it was already reported in 1930 by Rick. The species is characterized by the acuminate, pileus with hygrophanous surface, basidiospores measuring 11.5–16 × 5.5–11 µm and slender, non-capitate cheilocystidia. A full description accompanies photographs, line drawings and taxonomic discussion. Key words – Agaricomycotina – Basidiomycota – biodiversity – dark-spored – Panaeoloideae – Rick Introduction Species of Panaeolus (Fr.) Quél. -

Chemical Elements in Ascomycetes and Basidiomycetes

Chemical elements in Ascomycetes and Basidiomycetes The reference mushrooms as instruments for investigating bioindication and biodiversity Roberto Cenci, Luigi Cocchi, Orlando Petrini, Fabrizio Sena, Carmine Siniscalco, Luciano Vescovi Editors: R. M. Cenci and F. Sena EUR 24415 EN 2011 1 The mission of the JRC-IES is to provide scientific-technical support to the European Union’s policies for the protection and sustainable development of the European and global environment. European Commission Joint Research Centre Institute for Environment and Sustainability Via E.Fermi, 2749 I-21027 Ispra (VA) Italy Legal Notice Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of this publication. Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server http://europa.eu/ JRC Catalogue number: LB-NA-24415-EN-C Editors: R. M. Cenci and F. Sena JRC65050 EUR 24415 EN ISBN 978-92-79-20395-4 ISSN 1018-5593 doi:10.2788/22228 Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union Translation: Dr. Luca Umidi © European Union, 2011 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged Printed in Italy 2 Attached to this document is a CD containing: • A PDF copy of this document • Information regarding the soil and mushroom sampling site locations • Analytical data (ca, 300,000) on total samples of soils and mushrooms analysed (ca, 10,000) • The descriptive statistics for all genera and species analysed • Maps showing the distribution of concentrations of inorganic elements in mushrooms • Maps showing the distribution of concentrations of inorganic elements in soils 3 Contact information: Address: Roberto M. -

Baeocystin in Psilocybe, Conocybe and Panaeolus

Baeocystin in Psilocybe, Conocybe and Panaeolus DAVIDB. REPKE* P.O. Box 899, Los Altos, California 94022 and DALE THOMASLESLIE 104 Whitney Avenue, Los Gatos, California 95030 and GAST6N GUZMAN Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biologicas, l.P.N. Apartado Postal 26-378, Mexico 4. D.F. ABSTRACT.--Sixty collections of ten species referred to three families of the Agaricales have been analyzed for the presence of baeocystin by thin-layer chro- matography. Baeocystin was detected in collections of Peilocy be, Conocy be, and Panaeolus from the U.S.A., Canada, Mexico, and Peru. Laboratory cultivated fruit- bodies of Psilocybe cubensis, P. sernilanceata, and P. cyanescens were also studied. Intra-species variation in the presence and decay rate of baeocystin, psilocybin, and psilocin are discussed in terms of age and storage factors. In addition, evidence is presented to support the presence of 4-hydroxytryptamine in collections of P. baeo- cystis and P. cyanescens. The possible significance of baeocystin and 4·hydroxy- tryptamine in the biosynthesis of psilocybin in these organisms is discussed. A recent report (1) described the isolation of baeocystin [4-phosphoryloxy-3- (2-methylaminoethyl)indole] from collections of Psilocy be semilanceata (Fr.) Kummer. Previously, baeocystin had been detected only in Psilocybe baeo- cystis Singer and Smith (2, 3). This report now describes some further obser- vations regarding the occurrence of baeocystin in species referred to three families of Agaricales. Stein, Closs, and Gabel (4) isolated a compound from an agaric that they described as Panaeolus venenosus Murr., a species which is now considered synonomous with Panaeolus subbaIteatus (Berk. and Br.) Sacco (5, 6). -

Bulk Isolation of Basidiospores from Wild Mushrooms by Electrostatic Attraction with Low Risk of Microbial Contaminations Kiran Lakkireddy1,2 and Ursula Kües1,2*

Lakkireddy and Kües AMB Expr (2017) 7:28 DOI 10.1186/s13568-017-0326-0 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access Bulk isolation of basidiospores from wild mushrooms by electrostatic attraction with low risk of microbial contaminations Kiran Lakkireddy1,2 and Ursula Kües1,2* Abstract The basidiospores of most Agaricomycetes are ballistospores. They are propelled off from their basidia at maturity when Buller’s drop develops at high humidity at the hilar spore appendix and fuses with a liquid film formed on the adaxial side of the spore. Spores are catapulted into the free air space between hymenia and fall then out of the mushroom’s cap by gravity. Here we show for 66 different species that ballistospores from mushrooms can be attracted against gravity to electrostatic charged plastic surfaces. Charges on basidiospores can influence this effect. We used this feature to selectively collect basidiospores in sterile plastic Petri-dish lids from mushrooms which were positioned upside-down onto wet paper tissues for spore release into the air. Bulks of 104 to >107 spores were obtained overnight in the plastic lids above the reversed fruiting bodies, between 104 and 106 spores already after 2–4 h incubation. In plating tests on agar medium, we rarely observed in the harvested spore solutions contamina- tions by other fungi (mostly none to up to in 10% of samples in different test series) and infrequently by bacteria (in between 0 and 22% of samples of test series) which could mostly be suppressed by bactericides. We thus show that it is possible to obtain clean basidiospore samples from wild mushrooms. -

Checklist of the Argentine Agaricales 2. Coprinaceae and Strophariaceae

Checklist of the Argentine Agaricales 2. Coprinaceae and Strophariaceae 1 2* N. NIVEIRO & E. ALBERTÓ 1Instituto de Botánica del Nordeste (UNNE-CONICET). Sargento Cabral 2131, CC 209 Corrientes Capital, CP 3400, Argentina 2Instituto de Investigaciones Biotecnológicas (UNSAM-CONICET) Intendente Marino Km 8.200, Chascomús, Buenos Aires, CP 7130, Argentina *CORRESPONDENCE TO: [email protected] ABSTRACT—A checklist of species belonging to the families Coprinaceae and Strophariaceae was made for Argentina. The list includes all species published till year 2011. Twenty-one genera and 251 species were recorded, 121 species from the family Coprinaceae and 130 from Strophariaceae. KEY WORDS—Agaricomycetes, Coprinus, Psathyrella, Psilocybe, Stropharia Introduction This is the second checklist of the Argentine Agaricales. Previous one considered the families Amanitaceae, Pluteaceae and Hygrophoraceae (Niveiro & Albertó, 2012). Argentina is located in southern South America, between 21° and 55° S and 53° and 73° W, covering 3.7 million of km². Due to the large size of the country, Argentina has a wide variety of climates (Niveiro & Albertó, 2012). The incidence of moist winds coming from the oceans, the Atlantic in the north and the Pacific in the south, together with different soil types, make possible the existence of many types of vegetation adapted to different climatic conditions (Brown et al., 2006). Mycologists who studied the Agaricales from Argentina during the last century were reviewed by Niveiro & Albertó (2012). It is considered that the knowledge of the group is still incomplete, since many geographic areas in Argentina have not been studied as yet. The checklist provided here establishes a baseline of knowledge about the diversity of species described from Coprinaceae and Strophariaceae families in Argentina, and serves as a resource for future studies of mushroom biodiversity. -

New Record Species of Strophariaceae from Pakistan

RAZAQ AND SHAHZAD (2015), FUUAST J. BIOL., 5(1): 13-15 NEW RECORD SPECIES OF STROPHARIACEAE FROM PAKISTAN ABDUL RAZAQ1 AND SALEEM SHAHZAD2 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Karakoram International University, Gilgit-Baltistan. 2 Department of Agriculture & Agribusiness Management, University of Karachi, Karachi-75270, Pakistan. Correspondence author e-mail [email protected] Abstract The species viz., Panaeolus papilionaceus (Fr.) Quel, Panaeolus sphinctrinus (Fr.) Staude and Stropharia hornimannii (Fr.) Lund belonging to family Strophariaceae and order Agaricales are described. The Panaeolus papilionaceus and P. sphinctrinus are characterized by at first bell shaped are describe cap, convex then flattened, slightly umbonate. Stem smooth, radially vained, tapering slightly upwards or equal, slender. Gills fairly crowded and adenate. Spore print black. Smell indistinct. Spores ellipsoid, smooth. While the Stropharia hornimannii have at first convex then flattened, sticky and, smooth cap. Stem tapering slightly downwards, rather stout, ring present near the cap. Gills fairly crowded, adnate. Spore print brown. Smell unpleasant. Spores ellipsoid, smooth. Introduction Phylum Basidiomycota is a common group of fungi found all over the world that includes at least 22,244 species (Hawkworth et al., 1995). The group is large and divers, comprising of forms commonly known as mushrooms, boletus, puffballs, earthstars, stinkhorns, birds nest fungi, jelly fungi, bracket or shelf fungi, rust and smut fungi (Alexopolus et al., 1996). Basidiomycetes are characterized primarily by the sexual spores (basidiospores) being produced on a cell called a basidium, usually in four. Many but not all have septal structures called a clamp connection during most of the life cycle. No other group of fungi has these. -

Please Scroll Down for Article

This article was downloaded by: [Reynaud-Maurupt, Catherine] On: 22 October 2009 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 916144473] Publisher Informa Healthcare Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Substance Use & Misuse Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713597302 The Contemporary Uses of Hallucinogenic Plants and Mushrooms: A Qualitative Exploratory Study Carried Out in France Catherine Reynaud-Maurupt a; Agnès Cadet-Taïrou b; Anne Zoll c a Research Group into Social Vulnerability [Groupe de Recherche sur la Vulnérabilité Sociale (GRVS)], Levens, France b French Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction [Observatoire Français des Drogues et des Toxicomanies (OFDT)], Saint Denis La Plaine, France c Société d'Entraide et D'Action Psychologique (SEDAP), Dijon, France Online Publication Date: 01 September 2009 To cite this Article Reynaud-Maurupt, Catherine, Cadet-Taïrou, Agnès and Zoll, Anne(2009)'The Contemporary Uses of Hallucinogenic Plants and Mushrooms: A Qualitative Exploratory Study Carried Out in France',Substance Use & Misuse,44:11,1519 — 1552 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.3109/10826080802490170 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/10826080802490170 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. -

The Mycological Legacy of Elias Magnus Fries

The mycological legacy of Elias Magnus Fries Petersen, Ronald H.; Knudsen, Henning Published in: IMA Fungus DOI: 10.5598/imafungus.2015.06.01.04 Publication date: 2015 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: CC BY-NC-ND Citation for published version (APA): Petersen, R. H., & Knudsen, H. (2015). The mycological legacy of Elias Magnus Fries. IMA Fungus, 6(1), 99- 114. https://doi.org/10.5598/imafungus.2015.06.01.04 Download date: 26. sep.. 2021 IMA FUNGUS · 6(1): 99–114 (2015) doi:10.5598/imafungus.2015.06.01.04 ARTICLE The mycological legacy of Elias Magnus Fries Ronald H. Petersen1, and Henning Knudsen2 1Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, 37996–1100 USA; corresponding author e–mail: [email protected] 2Natural History Museum, University of Copenhagen, Oester Farimagsgade 2 C, 1353 Copenhagen, Denmark Abstract: The taxonomic concepts which originated with or were accepted by Elias Magnus Fries Key words: were presented during his lifetime in the printed word, illustrative depiction, and in collections of dried Biography specimens. This body of work was welcomed by the mycological and botanical communities of his time: Fungi students and associates aided Fries and after his passing carried forward his taxonomic ideas. His legacy Systema mycologicum spawned a line of Swedish and Danish mycologists intent on perpetuating the Fries tradition: Hampus Taxonomy von Post, Lars Romell, Seth Lundell and John Axel Nannfeldt in Sweden; Emil Rostrup, Severin Petersen Uppsala and Jakob Lange in Denmark. Volumes of color paintings and several exsiccati, most notably one edited by Lundell and Nannfeldt attached fungal portraits and preserved specimens (and often photographs) to Fries names. -

Diversity of Coprophilous Species of Panaeolus (Psathyrellaceae, Agaricales) from Punjab, India

BIODIVERSITAS ISSN: 1412-033X Volume 15, Number 2, October 2014 E-ISSN: 2085-4722 Pages: 115-130 DOI: 10.13057/biodiv/d150202 Diversity of coprophilous species of Panaeolus (Psathyrellaceae, Agaricales) from Punjab, India AMANDEEP KAUR1,♥, N.S. ATRI2, MUNRUCHI KAUR2 1Desh Bhagat College of Education, Bardwal-Dhuri-148024, Punjab, India. Tel.: +91-98152-49537; Fax.: +0175-304-6265; ♥email:[email protected]. 2Department of Botany, Punjabi University, Patiala-147002, Punjab, India. Manuscript received: 31 July 2014. Revision accepted: 1 September 2014. ABSTRACT Kaur A, Atri NS, Kaur M. 2014. Diversity of coprophilous species of Panaeolus (Psathyrellaceae, Agaricales) from Punjab, India. Biodiversitas 15: 115-130. An account of 16 Panaeolus species collected from a variety of coprophilous habitats of Punjab state in India is described and discussed. Out of these, P. alcidis, P. castaneifolius, P. papilionaceus var. parvisporus, P. tropicalis and P. venezolanus are new records for India while P. acuminatus, P. antillarum, P. ater, P. solidipes, and P. sphinctrinus are new reports for north India. Panaeolus subbalteatus and P. cyanescens are new records for Punjab state. A key to the taxa explored is also provided. Key words: Dung, epithelial pileus cuticle, systematics, taxonomy. INTRODUCTION MATERIALS AND METHODS The genus Panaeolus (Fr.) Quél., belonging to the Study area family Psathyrellaceae Readhead, Vilgalys & Hopple, is The state of Punjab is located in the north-western part characterized by its usually coprophilous habitat, bluing of India covering an area of 50,362 sq. km. which context, epithelial pileipellis, metulloidal chrysocystidia constitutes 1.57% of the total geographical area of the and spores which do not fade in concentrated sulphuric country. -

Sequencing Abstracts Msa Annual Meeting Berkeley, California 7-11 August 2016

M S A 2 0 1 6 SEQUENCING ABSTRACTS MSA ANNUAL MEETING BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 7-11 AUGUST 2016 MSA Special Addresses Presidential Address Kerry O’Donnell MSA President 2015–2016 Who do you love? Karling Lecture Arturo Casadevall Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Thoughts on virulence, melanin and the rise of mammals Workshops Nomenclature UNITE Student Workshop on Professional Development Abstracts for Symposia, Contributed formats for downloading and using locally or in a Talks, and Poster Sessions arranged by range of applications (e.g. QIIME, Mothur, SCATA). 4. Analysis tools - UNITE provides variety of analysis last name of primary author. Presenting tools including, for example, massBLASTer for author in *bold. blasting hundreds of sequences in one batch, ITSx for detecting and extracting ITS1 and ITS2 regions of ITS 1. UNITE - Unified system for the DNA based sequences from environmental communities, or fungal species linked to the classification ATOSH for assigning your unknown sequences to *Abarenkov, Kessy (1), Kõljalg, Urmas (1,2), SHs. 5. Custom search functions and unique views to Nilsson, R. Henrik (3), Taylor, Andy F. S. (4), fungal barcode sequences - these include extended Larsson, Karl-Hnerik (5), UNITE Community (6) search filters (e.g. source, locality, habitat, traits) for 1.Natural History Museum, University of Tartu, sequences and SHs, interactive maps and graphs, and Vanemuise 46, Tartu 51014; 2.Institute of Ecology views to the largest unidentified sequence clusters and Earth Sciences, University of Tartu, Lai 40, Tartu formed by sequences from multiple independent 51005, Estonia; 3.Department of Biological and ecological studies, and for which no metadata Environmental Sciences, University of Gothenburg, currently exists.