Considering a Cadre Augmented Army

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

Commander Ship Port Tons Mate Gunner Boatswain Carpenter Cook

www.1812privateers.org ©Michael Dun Commander Ship Port Tons Mate Gunner Boatswain Carpenter Cook Surgeon William Auld Dalmarnock Glasgow 315 John Auld Robert Miller Peter Johnston Donald Smith Robert Paton William McAlpin Robert McGeorge Diana Glasgow 305 John Dal ? Henry Moss William Long John Birch Henry Jukes William Morgan William Abrams Dunlop Glasgow 331 David Hogg John Williams John Simpson William James John Nelson - Duncan Grey Eclipse Glasgow 263 James Foulke Martin Lawrence Joseph Kelly John Kerr Robert Moss - John Barr Cumming Edward Glasgow 236 John Jenkins James Lee Richard Wiles Thomas Long James Anderson William Bridger Alexander Hardie Emperor Alexander Glasgow 327 John Jones William Jones John Thomas William Thomas James Williams James Thomas Thomas Pollock Lousia Glasgow 324 Alexander McLauren Robert Caldwell Solomon Piike John Duncan James Caldwell none John Bald Maria Glasgow 309 Charles Nelson James Cotton? John George Thomas Wood William Lamb Richard Smith James Bogg Monarch Glasgow 375 Archibald Stewart Thomas Boutfield William Dial Lachlan McLean Donald Docherty none George Bell Bellona Greenock 361 James Wise Thomas Jones Alexander Wigley Philip Johnson Richard Dixon Thomas Dacers Daniel McLarty Caesar Greenock 432 Mathew Simpson John Thomson William Wilson Archibald Stewart Donald McKechnie William Lee Thomas Boag Caledonia Greenock 623 Thomas Wills James Barnes Richard Lee George Hunt William Richards Charles Bailey William Atholl Defiance Greenock 346 James McCullum Francis Duffin John Senston Robert Beck -

Military Use Handbook

National Interagency Fire Center Military Use Handbook 2021 This publication was produced by the National Interagency Coordination Center (NICC), located at the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC), Boise, Idaho. This publication is also available on the Internet at http://www.nifc.gov/nicc/logistics/references.htm. MILITARY USE HANDBOOK 2021 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. ………………… ..................................................................................................................................................... CHAPTER 10 – GENERAL ........................................................................................................ 1 10.1 Purpose ............................................................................................................... 1 10.2 Overview .............................................................................................................. 1 10.3 Ordering Requirements and Procedures .............................................................. 1 10.4 Authorities/Responsibilities .................................................................................. 2 10.5 Billing Procedures ................................................................................................ 3 CHAPTER 20 – RESOURCE ORDERING PROCEDURES FOR MILITARY ASSETS ............... 4 20.1 Ordering Process ................................................................................................. 4 20.2 Demobilization -

America's Military Reserve in the All-Volunteer Era: from Strategic To

America’s Military Reserve in the All-Volunteer Era: From Strategic to Operational Adapted from remarks by Maj. Gen. Jeffrey E. Phillips, U.S. Army (Ret.), at the March 28 All- Volunteer Force Forum Conference 2019, Angelo State University, San Angelo, Texas Good afternoon and thank you for the invitation to once again be in my adopted Lone Star State, whose beloved name, as all who have lived here know, is spelled without an “A” – Tex-Iss. My friend Maj. Gen. Denny Laich [who had spoken earlier in the conference] has occupied a leading role in the All-Volunteer Force reality show; his work on the topic defines the argument that the AVF is inadequate for the nation’s future – and that now is the time to seriously explore what we should do about the situation. We owe him our thanks for his dedication to the continued security of our nation and the well- being of those who serve in our military. The Pentagon, in its November 2018 end-of-year report on recruiting and retention, disclosed some deficiencies that reinforce any perception that the all-volunteer force is in trouble. The U.S. Army’s accessions were nearly 7,000 under its already reduced annual goal. Neither the Army National Guard nor the Army Reserve made their recruiting goal – the Army Reserve missing by nearly 30 percent. None of the three made their number. The Air National Guard and the Navy Reserve also failed to make their recruiting goals. DoD officials on a budget conference call earlier this month explained that increased enlistment bonuses, more and better advertising, better coordination of marketing, and more and better recruiting would make the difference. -

Thomas Woodrow Wilson James Madison* James Monroe* Edith

FAMOUS MEMBERS OF THE JEFFERSON SOCIETY PRESIDENTS OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Thomas Woodrow Wilson James Madison∗ James Monroe∗ FIRST LADIES OF THE UNITED STATES Edith Bolling Galt Wilson∗ PRIME MINISTERS OF THE UNITED KINGDOM Margaret H. Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher∗ SPEAKERS OF THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter UNITED STATES SENATORS Oscar W. Underwood, Senate Minority Leader, Alabama Hugh Scott, Senate Minority Leader, Pennsylvania Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter, Virginia Willis P. Bocock, Virginia John S. Barbour Jr., Virginia Harry F. Byrd Jr., Virginia John Warwick Daniel, Virginia Claude A. Swanson, Virginia Charles J. Faulkner, West Virginia John Sharp Williams, Mississippi John W. Stevenson, Kentucky Robert Toombs, Georgia Clement C. Clay, Alabama Louis Wigfall, Texas Charles Allen Culberson, Texas William Cabell Bruce, Maryland Eugene J. McCarthy, Minnesota∗ James Monroe, Virginia∗ MEMBERS OF THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Oscar W. Underwood, House Majority Leader, Alabama John Sharp Williams, House Minority Leader, Mississippi Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter, Virginia Richard Parker, Virginia Robert A. Thompson, Virginia Thomas H. Bayly, Virginia Richard L. T. Beale, Virginia William Ballard Preston, Virginia John S. Caskie, Virginia Alexander H. H. Stuart, Virginia James Alexander Seddon, Virginia John Randolph Tucker, Virginia Roger A. Pryor, Virginia John Critcher, Virginia Colgate W. Darden, Virginia Claude A. Swanson, Virginia John S. Barbour Jr., Virginia William L. Wilson, West Virginia Wharton J. Green, North Carolina William Waters Boyce, South Carolina Hugh Scott, Pennsylvania Joseph Chappell Hutcheson, Texas John W. Stevenson, Kentucky Robert Toombs, Georgia Thomas W. Ligon, Maryland Augustus Maxwell, Florida William Henry Brockenbrough, Florida Eugene J. -

Sanctuary Lost: the Air War for ―Portuguese‖ Guinea, 1963-1974

Sanctuary Lost: The Air War for ―Portuguese‖ Guinea, 1963-1974 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Martin Hurley, MA Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Professor John F. Guilmartin, Jr., Advisor Professor Alan Beyerchen Professor Ousman Kobo Copyright by Matthew Martin Hurley 2009 i Abstract From 1963 to 1974, Portugal and the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde, or PAIGC) waged an increasingly intense war for the independence of ―Portuguese‖ Guinea, then a colony but today the Republic of Guinea-Bissau. For most of this conflict Portugal enjoyed virtually unchallenged air supremacy and increasingly based its strategy on this advantage. The Portuguese Air Force (Força Aérea Portuguesa, abbreviated FAP) consequently played a central role in the war for Guinea, at times threatening the PAIGC with military defeat. Portugal‘s reliance on air power compelled the insurgents to search for an effective counter-measure, and by 1973 they succeeded with their acquisition and employment of the Strela-2 shoulder-fired surface-to-air missile, altering the course of the war and the future of Portugal itself in the process. To date, however, no detailed study of this seminal episode in air power history has been conducted. In an international climate plagued by insurgency, terrorism, and the proliferation of sophisticated weapons, the hard lessons learned by Portugal offer enduring insight to historians and current air power practitioners alike. -

California State Military Reserve Establishes Maritime Component By: MAJ(CA)K.J

SPRING SDF Times 2017 Coming Soon! Presidents Message SDF Times - Next Edition 30 July 2017 Submission Deadline Our State Defense Forces stand at the threshold of even greater opportunity to serve our states and nation. The confluence of our federal budget crisis, state Items for Annual Conference Board Consideration budget difficulties, increased extreme weather systems and threats of terrorism, 1 August 2017 provide a challenging environment that our troops can provide a meaningful solu- Submission Deadline tion. We now have an established track record of excellence upon which we can build an even more elite force. 2017 SGAUS Annual Conference 21-24 September 2017 Myrtle Beach, SC Members of SGAUS, as you may know, I have just come off of a Chaplain Training & Conference 21-23 September 2017 whirlwind U.S. congressional cam- Myrtle Beach, SC paign launched with broad-based support. It was an extraordinary PAO/PIO Training & Conference 22 September 2017 experience in which the great suc- Myrtle Beach, SC cess of our South Carolina State Guard was made an issue. Judge Advocate & Engineer We enjoyed particularly strong Training & Conference 22-23 September 2017 support among military veterans Myrtle Beach, SC throughout the district and across the state. And we received MEMS & Medical Conference 23 September 2017 the published endorsements of Myrtle Beach, SC several of those veterans, includ- ing two MEDAL OF HONOR recipients – Maj. Gen. Jim SGAUS Stipend, Scholarship, & Soldier/NCO/Officer of the Year Livingston, U.S. Marine Corps (Ret.) and LT Mike Thornton, U.S. Navy SEALs (Ret.). Program Their stories by the way, like all recipients of our nation’s highest award for com- 15 March 2018 bat valor, are beyond remarkable. -

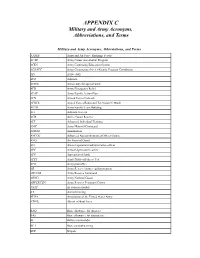

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

Henry Carter Stuart in Virginia Folitics 1855-1933

HENRY CARTER STUART IN VIRGINIA FOLITICS 1855-1933 Charles Evans Poston Columbia, South Carol i.na BoAo, University of Richmond, 1968 A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Corcoran Department of History University of Virginia June 1970 :.'.c\.EFACE lic'nry C;,i·tL:r Stu,n·t, Governor of Virginiu from 1914 to 1918, has been 3 ph,,ntom-like figure in Virginia history. Ile has never been subjected to the scrutiny of close and systematic study; ye� those familiar with his career, while not painting him as a wc�k governor, have not portraycci his administration as particularly striking either. Moreover, Stuart's relationship to the Demo cratic Party in the first two decades of this century is blurred. Some historians of the period place him squarely in the Martin org anization ranks as early as 1909; others consioer him an independent until 1920 at least. This essay seeks to clarify Stuart's political affilic1tions in Virginia. Moreover, while its sights are not firmly focused on hi� governorship, enough work has been done to indicate i i is major pcLicies as governor and to offer some evaluation of them. An iL-depth study of Stuart's a dministration, however, must await a iurcher study which is planned as a doctoral dissertation. The staff of the Virginia State Library in Richmond was most he��ful during the cowrsc o� researching the �a�cr, as was the sta:f of the University.of Virginia's Alderffi2n Li�rary. -

Prominent and Progressive Americans

PROMINENTND A PROGRESSIVE AMERICANS AN ENCYCLOPEDIA O F CONTEMPORANEOUS BIOGRAPHY COMPILED B Y MITCHELL C. HARRISON VOLUME I NEW Y ORK TRIBUNE 1902 THEEW N YORK public l h:::ary 2532861S ASTIMI. l .;-M':< AND TILI'EN ! -'.. VDAT.ON8 R 1 P43 I Copyright, 1 902, by Thb Tribune Association Thee D Vinne Prem CONTENTS PAGE Frederick T hompson Adams 1 John G iraud Agar 3 Charles H enry Aldrich 5 Russell A lexander Alger 7 Samuel W aters Allerton 10 Daniel P uller Appleton 15 John J acob Astor 17 Benjamin F rankldi Ayer 23 Henry C linton Backus 25 William T . Baker 29 Joseph C lark Baldwin 32 John R abick Bennett 34 Samuel A ustin Besson 36 H.. S Black 38 Frank S tuart Bond 40 Matthew C haloner Durfee Borden 42 Thomas M urphy Boyd 44 Alonzo N orman Burbank 46 Patrick C alhoun 48 Arthur J ohn Caton 53 Benjamin P ierce Cheney 55 Richard F loyd Clarke 58 Isaac H allowell Clothier 60 Samuel P omeroy Colt 65 Russell H ermann Conwell 67 Arthur C oppell 70 Charles C ounselman 72 Thomas C ruse 74 John C udahy 77 Marcus D aly 79 Chauncey M itchell Depew 82 Guy P helps Dodge 85 Thomas D olan 87 Loren N oxon Downs 97 Anthony J oseph Drexel 99 Harrison I rwln Drummond 102 CONTENTS PAGE John F airfield Dryden 105 Hipolito D umois 107 Charles W arren Fairbanks 109 Frederick T ysoe Fearey Ill John S cott Ferguson 113 Lucius G eorge Fisher 115 Charles F leischmann 118 Julius F leischmann 121 Charles N ewell Fowler ' 124 Joseph. -

1201 Eff Reply Comments Class

Before the U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS In the matter of Exemption to Prohibition on Circumvention of Copyright Protection Systems for Access Control Technologies Under 17 U.S.C. 1201 Docket No. 2014-07 Comments of Electronic Frontier Foundation 1. Commenter Information: Kit Walsh Counsel for EFF: Corynne McSherry Marcia Hofmann Mitch Stoltz Law Office of Marcia Hofmann Electronic Frontier Foundation 25 Taylor Street 815 Eddy Street San Francisco, CA 94102 San Francisco, CA 94109 (415) 830-6664 (415) 436-9333 [email protected] 2. Proposed Class Addressed Proposed Class 22: Vehicle Software —Security and Safety Research This proposed class would allow circumvention of TPMs protecting computer programs that control the functioning of a motorized land vehicle, [including programs that modify the code or data stored in such a vehicle and including compilations of data used in controlling or analyzing the functioning of such a vehicle,] for the purpose of researching the security or safety of such vehicles. Under the exemption as proposed, circumvention would be allowed when undertaken by or on behalf of the lawful owner of the vehicle [or computer to which the computer program or data compilation relates].1 In addition to computer programs actually embedded or designed to be embedded in a motorized land vehicle, the exemption as proposed and discussed by EFF includes computer programs designed to modify the memory of embedded hardware. This comment uses the terms “vehicle firmware” or “vehicle software” interchangeably to refer to all the works falling within the proposed class. 3. Overview It is not an infringement of copyright to engage in security and safety research. -

NATO and the Reorganization Portuguese Army Staff Corps Instruction in the 1950’S

Bulletin for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies Journal of the Association for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies Volume 37 | Issue 1 Article 7 2012 NATO and the reorganization Portuguese Army Staff orC ps instruction in the 1950’s Daniel Marcos FCSH and IPRI/UNL, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.asphs.net/bsphs Recommended Citation Marcos, Daniel (2012) "NATO and the reorganization Portuguese Army Staff orC ps instruction in the 1950’s," Bulletin for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies: Vol. 37 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. https://doi.org/10.26431/0739-182X.1060 Available at: https://digitalcommons.asphs.net/bsphs/vol37/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Association for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bulletin for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies by an authorized editor of Association for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BULLETIN FOR SPANISH AND PORTUGUESE HISTORICAL STUDIES 37:1/December 2012/130-145 NATO and the reorganization Portuguese Army Staff Corps instruction in the 1950’s Daniel marcos FCSH and IPRI-University of Lisbon In what concerned its defense policy, Portugal’s participation in NATO as a founding member brought great consequences to the Portuguese authoritarian regime of Estado Novo . As one renowned Portuguese historian puts it, the first years of Portugal in NATO were a “quiet revolution” that changed the Portuguese Armed Forces since it allowed the incorporation of foreign techniques and methods, especially the ones used by the US Armed Forces.1 Particularly to the Portuguese Army, this modernization had clear impacts on the instruction and training of the General Staff officers and, consequently, to the Portuguese Army Staff Corps (ASC).