Japans Self- Defense Forces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military Use Handbook

National Interagency Fire Center Military Use Handbook 2021 This publication was produced by the National Interagency Coordination Center (NICC), located at the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC), Boise, Idaho. This publication is also available on the Internet at http://www.nifc.gov/nicc/logistics/references.htm. MILITARY USE HANDBOOK 2021 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. ………………… ..................................................................................................................................................... CHAPTER 10 – GENERAL ........................................................................................................ 1 10.1 Purpose ............................................................................................................... 1 10.2 Overview .............................................................................................................. 1 10.3 Ordering Requirements and Procedures .............................................................. 1 10.4 Authorities/Responsibilities .................................................................................. 2 10.5 Billing Procedures ................................................................................................ 3 CHAPTER 20 – RESOURCE ORDERING PROCEDURES FOR MILITARY ASSETS ............... 4 20.1 Ordering Process ................................................................................................. 4 20.2 Demobilization -

Sanctuary Lost: the Air War for ―Portuguese‖ Guinea, 1963-1974

Sanctuary Lost: The Air War for ―Portuguese‖ Guinea, 1963-1974 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Martin Hurley, MA Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Professor John F. Guilmartin, Jr., Advisor Professor Alan Beyerchen Professor Ousman Kobo Copyright by Matthew Martin Hurley 2009 i Abstract From 1963 to 1974, Portugal and the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde, or PAIGC) waged an increasingly intense war for the independence of ―Portuguese‖ Guinea, then a colony but today the Republic of Guinea-Bissau. For most of this conflict Portugal enjoyed virtually unchallenged air supremacy and increasingly based its strategy on this advantage. The Portuguese Air Force (Força Aérea Portuguesa, abbreviated FAP) consequently played a central role in the war for Guinea, at times threatening the PAIGC with military defeat. Portugal‘s reliance on air power compelled the insurgents to search for an effective counter-measure, and by 1973 they succeeded with their acquisition and employment of the Strela-2 shoulder-fired surface-to-air missile, altering the course of the war and the future of Portugal itself in the process. To date, however, no detailed study of this seminal episode in air power history has been conducted. In an international climate plagued by insurgency, terrorism, and the proliferation of sophisticated weapons, the hard lessons learned by Portugal offer enduring insight to historians and current air power practitioners alike. -

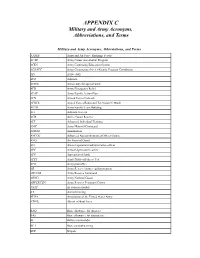

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

NATO and the Reorganization Portuguese Army Staff Corps Instruction in the 1950’S

Bulletin for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies Journal of the Association for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies Volume 37 | Issue 1 Article 7 2012 NATO and the reorganization Portuguese Army Staff orC ps instruction in the 1950’s Daniel Marcos FCSH and IPRI/UNL, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.asphs.net/bsphs Recommended Citation Marcos, Daniel (2012) "NATO and the reorganization Portuguese Army Staff orC ps instruction in the 1950’s," Bulletin for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies: Vol. 37 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. https://doi.org/10.26431/0739-182X.1060 Available at: https://digitalcommons.asphs.net/bsphs/vol37/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Association for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bulletin for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies by an authorized editor of Association for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BULLETIN FOR SPANISH AND PORTUGUESE HISTORICAL STUDIES 37:1/December 2012/130-145 NATO and the reorganization Portuguese Army Staff Corps instruction in the 1950’s Daniel marcos FCSH and IPRI-University of Lisbon In what concerned its defense policy, Portugal’s participation in NATO as a founding member brought great consequences to the Portuguese authoritarian regime of Estado Novo . As one renowned Portuguese historian puts it, the first years of Portugal in NATO were a “quiet revolution” that changed the Portuguese Armed Forces since it allowed the incorporation of foreign techniques and methods, especially the ones used by the US Armed Forces.1 Particularly to the Portuguese Army, this modernization had clear impacts on the instruction and training of the General Staff officers and, consequently, to the Portuguese Army Staff Corps (ASC). -

Considering a Cadre Augmented Army

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore Pardee RAND Graduate School View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the Pardee RAND Graduate School (PRGS) dissertation series. PRGS dissertations are produced by graduate fellows of the Pardee RAND Graduate School, the world’s leading producer of Ph.D.’s in policy analysis. The dissertation has been supervised, reviewed, and approved by the graduate fellow’s faculty committee. Considering a Cadre Augmented Army Christopher Ordowich This document was submitted as a dissertation in June 2008 in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the doctoral degree in public policy analysis at the Pardee RAND Graduate School. -

USASI Workshop Report April 2018 Final.Indd

Assessing the E ectiveness of Alliance Responses to Regional and Global Threats Workshop Findings and Policy Recommendations ..- Stanford University The Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Paci c Research Center Encina Hall Stanford, CA 94305-6055 CONFERENCE REPORT | MAY 2018 Phone: 650.724.5647 Fax: 650.723.6530 aparc.fsi.stanford.edu/research/us-asia-security-initiative U.S.-Asia U.S.-Asia Security Initiative Security Initiative The U.S.-Asia Security Initiative U.S.-Japan Security and Defense Dialogue Series Assessing the Effectiveness of Alliance Responses to Regional and Global Threats Workshop Findings and Policy Recommendations 31 January–2 February 2018 Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan Sponsored by the U.S.-Asia Security Initiative Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies Stanford University In conjunction with The Sasakawa Peace Foundation Support for this workshop, the second in the U.S.-Japan Security and Defense Dialogue, was provided in part by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York. CONFERENCE REPORT | may 2018 U.S.-Asia Security Initiative above: (November 14, 2006) Aircraft assigned to Carrier Air Wing Five (CVW-5) fly over a group of eighteen U.S. Navy and Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force ships, at the conclusion of the two nations’ aNNUaLeX exercise. The exercise is designed to improve both forces’ capabilities in the defense of Japan. Credit: U.S. Navy photo by MaSS CoMMUNiCatioN SpeCiaLiSt 3rd CLaSS Jarod hodge. Cover: (June 1, 2017) USS Carl Vinson (CVN 70) and USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76) sail alongside the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force’s JS Hyuga (DDH 181) during dual carrier strike group operations in the Sea of Japan. -

FEMA IS-75: Military Resources in Emergency Management (May 2011) Toc I FEMA IS-75: Military Resources in Emergency Management Table of Contents

FEMA IS-75: Military Resources in Emergency Management Table of Contents Table of Contents Course Introduction .................................................................................................................... SM CI-1 Course Objectives ................................................................................................................... SM CI-4 Course Agenda ....................................................................................................................... SM CI-5 Course Administrative Details.................................................................................................. SM CI-7 Lesson 1: Types of Military Response and Integration of Military Support...................................... SM I-1 Topics Covered .......................................................................................................................... SM I-2 Objectives .................................................................................................................................. SM I-3 Defense Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA) .............................................................................. SM I-4 Levels of Response .................................................................................................................... SM I-8 Types of Military Response ...................................................................................................... SM I-11 Representatives in a Federal Response .................................................................................. -

Managing the U.S.-Japan Alliance: an Examination of Structural Linkages in the Security Relationship

Managing the U.S.-Japan Alliance: An Examination of Structural Linkages in the Security Relationship Jeffrey W. Hornung ^ĂƐĂŬĂǁĂWĞĂĐĞ&ŽƵŶĚĂƟŽŶh^ MANAGING THE U.S.-JAPAN ALLIANCE MANAGING THE U.S.-JAPAN ALLIANCE AN EXAMINATION OF STRUCTURAL LINKAGES IN THE SECURITY RELATIONSHIP Jeffrey W. Hornung Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA is an independent, American non-profit and non-partisan institution devoted to research, analysis, and better understanding of the U.S.–Japan relationship. Sasakawa USA accomplishes its mission through programs that benefit both nations and the broader Asia-Pacific region. Our research programs focus on security, diplomacy, economics, trade, and technology, and our education programs facilitate people- to-people exchange and discussion among American and Japanese policymakers, influential citizens, and the broader public in both countries. ISBN 978-0-9966567-7-1 Printed in the United States of America © 2017 by Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA Sasakawa USA does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views expressed herein are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect the views of Sasakawa USA, its staff, or its board. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from Sasakawa USA. Please direct inquiries to: Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA Research Department 1819 L St NW #300 Washington, DC 20036 P: +1 202-296-6694 E: [email protected] This publication can be downloaded at no cost at https://spfusa.org/. Contents Abbreviations