Scientific Naming of Plants: Nomenclature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Scope and Importance of Taxonomy. Classification of Angiosperms- Bentham and Hooker System & Cronquist

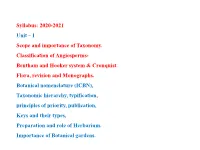

Syllabus: 2020-2021 Unit – I Scope and importance of Taxonomy. Classification of Angiosperms- Bentham and Hooker system & Cronquist. Flora, revision and Monographs. Botanical nomenclature (ICBN), Taxonomic hierarchy, typification, principles of priority, publication, Keys and their types, Preparation and role of Herbarium. Importance of Botanical gardens. PLANT KINGDOM Amongst plants nearly 15,000 species belong to Mosses and Liverworts, 12,700 Ferns and their allies, 1,079 Gymnosperms and 295,383 Angiosperms (belonging to about 485 families and 13,372 genera), considered to be the most recent and vigorous group of plants that have occurred on earth. Angiosperms occupy the majority of the terrestrial space on earth, and are the major components of the world‘s vegetation. Brazil (First) and Colombia (second), both located in the tropics considered to be countries with the most diverse angiosperms floras China (Third) even though the main part of her land is not located in the tropics, the number of angiosperms still occupies the third place in the world. In INDIA there are about 18042 species of flowering plants approximately 320 families, 40 genera and 30,000 species. IUCN Red list Categories: EX –Extinct; EW- Extinct in the Wild-Threatened; CR -Critically Endangered; VU- Vulnerable Angiosperm (Flowering Plants) SPECIES RICHNESS AROUND THE WORLD PLANT CLASSIFICATION Historia Plantarum - the earliest surviving treatise on plants in which Theophrastus listed the names of over 500 plant species. Artificial system of Classification Theophrastus attempted common groupings of folklore combined with growth form such as ( Tree Shrub; Undershrub); or Herb. Or (Annual and Biennials plants) or (Cyme and Raceme inflorescences) or (Archichlamydeae and Meta chlamydeae) or (Upper or Lower ovarian ). -

Mnemonic Memory Taxonomy

MNEMONIC MEMORY TAXONOMY Overview: In this lesson, students determine proper classification of organisms according to taxonomic levels, explore characteristics that determine classification, and create methods to recall ordered taxonomic terminology. Objectives: The student will: • describe the use and function of a taxonomy, specifically to order and classify living organisms; and • identify and list taxonomic levels of biological classification. Targeted Alaska Grade Level Expectations: Science [7] SC2.2 The student demonstrates an understanding of the structure, function, behavior, development, life cycles, and diversity of living organisms by identifying the seven levels of classification of organisms. [7] SA1.1 The student demonstrates an understanding of the processes of science by asking questions, predicting, observing, describing, measuring, classifying, makign generalizations, inferring, and communicating. Vocabulary: animalia— one of six kingdoms, including most living things that are able to move and digest food internally plantae –one of six kingdoms, including living things that generally manufacture their own food through the use of photosynthesis fungi – one of six kingdoms, mostly living things that are nonmobile and assist in the decomposition process, including yeasts, molds, and mushrooms binomial nomenclature – a scientific naming system that gives a unique name (“scientific name”) to each species, using organisms’ genus and species as its two parts (e.g., “Homo sapiens” for humans) class – a taxonomic rank below -

Review and Updated Checklist of Freshwater Fishes of Iran: Taxonomy, Distribution and Conservation Status

Iran. J. Ichthyol. (March 2017), 4(Suppl. 1): 1–114 Received: October 18, 2016 © 2017 Iranian Society of Ichthyology Accepted: February 30, 2017 P-ISSN: 2383-1561; E-ISSN: 2383-0964 doi: 10.7508/iji.2017 http://www.ijichthyol.org Review and updated checklist of freshwater fishes of Iran: Taxonomy, distribution and conservation status Hamid Reza ESMAEILI1*, Hamidreza MEHRABAN1, Keivan ABBASI2, Yazdan KEIVANY3, Brian W. COAD4 1Ichthyology and Molecular Systematics Research Laboratory, Zoology Section, Department of Biology, College of Sciences, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran 2Inland Waters Aquaculture Research Center. Iranian Fisheries Sciences Research Institute. Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization, Bandar Anzali, Iran 3Department of Natural Resources (Fisheries Division), Isfahan University of Technology, Isfahan 84156-83111, Iran 4Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 6P4 Canada *Email: [email protected] Abstract: This checklist aims to reviews and summarize the results of the systematic and zoogeographical research on the Iranian inland ichthyofauna that has been carried out for more than 200 years. Since the work of J.J. Heckel (1846-1849), the number of valid species has increased significantly and the systematic status of many of the species has changed, and reorganization and updating of the published information has become essential. Here we take the opportunity to provide a new and updated checklist of freshwater fishes of Iran based on literature and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history and new fish collections. This article lists 288 species in 107 genera, 28 families, 22 orders and 3 classes reported from different Iranian basins. However, presence of 23 reported species in Iranian waters needs confirmation by specimens. -

International Code of Zoological Nomenclature

International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature INTERNATIONAL CODE OF ZOOLOGICAL NOMENCLATURE Fourth Edition adopted by the International Union of Biological Sciences The provisions of this Code supersede those of the previous editions with effect from 1 January 2000 ISBN 0 85301 006 4 The author of this Code is the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature Editorial Committee W.D.L. Ride, Chairman H.G. Cogger C. Dupuis O. Kraus A. Minelli F. C. Thompson P.K. Tubbs All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise), without the prior written consent of the publisher and copyright holder. Published by The International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature 1999 c/o The Natural History Museum - Cromwell Road - London SW7 5BD - UK © International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature 1999 Explanatory Note This Code has been adopted by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature and has been ratified by the Executive Committee of the International Union of Biological Sciences (IUBS) acting on behalf of the Union's General Assembly. The Commission may authorize official texts in any language, and all such texts are equivalent in force and meaning (Article 87). The Code proper comprises the Preamble, 90 Articles (grouped in 18 Chapters) and the Glossary. Each Article consists of one or more mandatory provisions, which are sometimes accompanied by Recommendations and/or illustrative Examples. In interpreting the Code the meaning of a word or expression is to be taken as that given in the Glossary (see Article 89). -

Alyssum) and the Correct Name of the Goldentuft Alyssum

ARNOLDIA VE 1 A continuation of the BULLETIN OF POPULAR INFORMATION of the Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University VOLUME 26 JUNE 17, 1966 NUMBERS 6-7 ORNAMENTAL MADWORTS (ALYSSUM) AND THE CORRECT NAME OF THE GOLDENTUFT ALYSSUM of the standard horticultural reference works list the "Madworts" as MANYa group of annuals, biennials, perennials or subshrubs in the family Cru- ciferae, which with the exception of a few species, including the goldentuft mad- wort, are not widely cultivated. The purposes of this article are twofold. First, to inform interested gardeners, horticulturists and plantsmen that this exception, with a number of cultivars, does not belong to the genus Alyssum, but because of certain critical and technical characters, should be placed in the genus Aurinia of the same family. The second goal is to emphasize that many species of the "true" .~lyssum are notable ornamentals and merit greater popularity and cul- tivation. The genus Alyssum (now containing approximately one hundred and ninety species) was described by Linnaeus in 1753 and based on A. montanum, a wide- spread European species which is cultivated to a limited extent only. However, as medicinal and ornamental garden plants the genus was known in cultivation as early as 1650. The name Alyssum is of Greek derivation : a meaning not, and lyssa alluding to madness, rage or hydrophobia. Accordingly, the names Mad- wort and Alyssum both refer to the plant’s reputation as an officinal herb. An infu- sion concocted from the leaves and flowers was reputed to have been administered as a specific antidote against madness or the bite of a rabid dog. -

Botanical Nomenclature: Concept, History of Botanical Nomenclature

Module – 15; Content writer: AvishekBhattacharjee Module 15: Botanical Nomenclature: Concept, history of botanical nomenclature (local and scientific) and its advantages, formation of code. Content writer: Dr.AvishekBhattacharjee, Central National Herbarium, Botanical Survey of India, P.O. – B. Garden, Howrah – 711 103. Module – 15; Content writer: AvishekBhattacharjee Botanical Nomenclature:Concept – A name is a handle by which a mental image is passed. Names are just labels we use to ensure we are understood when we communicate. Nomenclature is a mechanism for unambiguous communication about the elements of taxonomy. Botanical Nomenclature, i.e. naming of plants is that part of plant systematics dealing with application of scientific names to plants according to some set rules. It is related to, but distinct from taxonomy. A botanical name is a unique identifier to which information of a taxon can be attached, thus enabling the movement of data across languages, scientific disciplines, and electronic retrieval systems. A plant’s name permits ready summarization of information content of the taxon in a nested framework. A systemofnamingplantsforscientificcommunicationmustbe international inscope,andmustprovideconsistencyintheapplicationof names.Itmustalsobeacceptedbymost,ifnotall,membersofthe scientific community. These criteria led, almost inevitably, to International Botanical Congresses (IBCs) being the venue at which agreement on a system of scientific nomenclature for plants was sought. The IBCs led to publication of different ‘Codes’ which embodied the rules and regulations of botanical nomenclature and the decisions taken during these Congresses. Advantages ofBotanical Nomenclature: Though a common name may be much easier to remember, there are several good reasons to use botanical names for plant identification. Common names are not unique to a specific plant. -

Taxonomic Review of the Genus Rosa

REVIEW ARTICLE Taxonomic Review of the Genus Rosa Nikola TOMLJENOVIĆ 1 ( ) Ivan PEJIĆ 2 Summary Species of the genus Rosa have always been known for their beauty, healing properties and nutritional value. Since only a small number of properties had been studied, attempts to classify and systematize roses until the 16th century did not give any results. Botanists of the 17th and 18th century paved the way for natural classifi cations. At the beginning of the 19th century, de Candolle and Lindley considered a larger number of morphological characters. Since the number of described species became larger, division into sections and subsections was introduced in the genus Rosa. Small diff erences between species and the number of transitional forms lead to taxonomic confusion and created many diff erent classifi cations. Th is problem was not solved in the 20th century either. In addition to the absence of clear diff erences between species, the complexity of the genus is infl uenced by extensive hybridization and incomplete sorting by origin, as well as polyploidy. Diff erent analytical methods used along with traditional, morphological methods help us clarify the phylogenetic relations within the genus and give a clearer picture of the botanical classifi cation of the genus Rosa. Molecular markers are used the most, especially AFLPs and SSRs. Nevertheless, phylogenetic relationships within the genus Rosa have not been fully clarifi ed. Th e diversity of the genus Rosa has not been specifi cally analyzed in Croatia until now. Key words Rosa sp., taxonomy, molecular markers, classifi cation, phylogeny 1 Agricultural School Zagreb, Gjure Prejca 2, 10040 Zagreb, Croatia e-mail: [email protected] 2 University of Zagreb, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Plant Breeding, Genetics and Biometrics, Svetošimunska cesta 25, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Received: November , . -

Multiflora Rose, Rosa Multiflora Thunb. Rosaceae

REGULATORY HORTICULTURE [Vol. 9, No.1-2] Weed Circular No. 6 Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture April & October 1983 Bureau of Plant Industry Multiflora Rose, Rosa multiflora Thunb. Rosaceae. Robert J. Hill I. Nomenclature: A) Rosa multiflora Thunb. (Fig. 1); B) Multiflora rose; C) Synonyms: Rosa Dawsoniana Hort., R. polyantha Sieb. & Zucc., R. polyanthos Roessia., R. thyrsiflora Leroy, R. intermedia, Carr., and R. Wichurae Kock. Fig. 1. Multiflora rose. A) berrylike hips, B)leaf, note pectinate stipules (arrow), C) stem (cane). II. History: The genus Rosa is a large group of plants comprised of about 150 species, of which one-third are indigenous to America. Gray's Manual of Botany (Fernald 1970) lists 24 species (13 native; 11 introduced, 10 of these fully naturalized) for our range. Gleason and Cronquist (l968) cite 19 species (10 introductions). The disagreement in the potential number of species encountered in Pennsylvania arises from the confused taxonomy of a highly variable and freely crossing group. In fact, there are probably 20,000 cultivars of Rosa known. Bailey (1963) succinctly states the problem: "In no other genus, perhaps, are the opinions of botanists so much at variance in regard to the number of species." The use of roses by mankind has a long history. The Romans acquired a love for roses from the Persians. After the fall of Rome, roses were transported by the Benedictine monks across the Alps, and by the 700's AD garden roses were growing in southern France. The preservation and expansion of these garden varieties were continued by monasteries and convents from whence they spread to castle gardens and gradually to more humble, secular abodes. -

The Nature of Naming What’S in a Name?

The Nature of Naming What’s in a Name? • "A rose is a rose," it has been said • And most of us know a rose when we see one • As we know the African marigolds • Maples, elms, cedars, and pines that shade our backyards and line our streets What’s in a Name? • We usually call these plants by their common names • But if we wanted to know more about the cedar tree in our front yard, we would find that "cedar" may refer to: – Eastern red cedar What’s in a Name? • Incense cedar What’s in a Name? • Western red cedar What’s in a Name? • Atlantic white cedar What’s in a Name? • Spanish cedar What’s in a Name? • Biblical Lebanon cedar What’s in a Name? • In fact, we would find that cedars are found in three separate plant families What’s in a Name? • Later, after discovering that our "African" marigolds are in fact from Mexico and our "Spanish" cedar originated in the West Indies, we would realize how misleading the common names of plants can be. What’s in a Name? • The same plant can have many different common names – European white lily has at least 245 – Marsh marigold has at least 280 What’s in a Name? • Clearly, if we use only the common name of a plant, we cannot be sure of understanding very much about that plant Classification • It is for this reason that the scientific community prefers to use a more precise way of naming, or classification • Scientific classification, however, is more than just naming: it is a key to understanding • Botanists name a plant to give it a unique place in the biological world, as well as to clarify its relationships within that world How Are Plants Classified? • Science classifies living things in an orderly system through which they can be easily identified – Categories of increasing size, based upon relationships within those categories How Are Plants Classified? • For example, all plants can be put in order from the more primitive to the more advanced. -

An Additional Nomenclatural Transfer in the Pantropical Genus Myrsine (Primulaceae: Myrsinoideae) John J

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks Marine & Environmental Sciences Faculty Articles Department of Marine and Environmental Sciences 9-13-2018 An Additional Nomenclatural Transfer in the Pantropical Genus Myrsine (Primulaceae: Myrsinoideae) John J. Pipoly III Broward County Parks & Recreation Division; Nova Southeastern University, [email protected] Jon M. Ricketson Missouri Botanical Garden Find out more information about Nova Southeastern University and the Halmos College of Natural Sciences and Oceanography. Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_facarticles Part of the Marine Biology Commons, and the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons NSUWorks Citation John J. Pipoly III and Jon M. Ricketson. 2018. An Additional Nomenclatural Transfer in the Pantropical Genus Myrsine (Primulaceae: Myrsinoideae) .Novon , (3) : 287 -287. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_facarticles/942. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Marine and Environmental Sciences at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marine & Environmental Sciences Faculty Articles by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Additional Nomenclatural Transfer in the Pantropical Genus Myrsine (Primulaceae: Myrsinoideae) John J. Pipoly III Broward County Parks & Recreation Division, 950 NW 38th St., Oakland Park, Florida 33309, U.S.A.; Nova Southeastern University, 8000 N Ocean Dr., Dania Beach, Florida 33004, U.S.A. [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Jon M. Ricketson Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Blvd., St. Louis, Missouri 63110, U.S.A. [email protected] ABSTRACT. Rapanea pellucidostriata Gilg & Schellenb. TYPE: Democratic Republic of the Congo. Ruwen- is transferred to Myrsine L. -

Guide to Plant Collection and Identification

GUIDE TO PLANT COLLECTION AND IDENTIFICATION by Jane M. Bowles PhD Originally prepared for a workshop in Plant Identification for the Ministry of Natural Resources in 1982. Edited and revised for the UWO Herbarium Workshop in Plant Collection and Identification, 2004 © Jane M. Bowles, 2004 -0- CHAPTER 1 THE NAMES OF PLANTS The history of plant nomenclature: Humans have always had a need to classify objects in the world about them. It is the only means they have of acquiring and passing on knowledge. The need to recognize and describe plants has always been especially important because of their use for food and medicinal purposes. The commonest, showiest or most useful plants were given common names, but usually these names varied from country to country and often from district to district. Scholars and herbalists knew the plants by a long, descriptive, Latin sentence. For example Cladonia rangiferina, the common "Reindeer Moss", was described as Muscus coralloides perforatum (The perforated, coral-like moss). Not only was this system unwieldy, but it too varied from user to user and with the use of the plant. In the late 16th century, Casper Bauhin devised a system of using just two names for each plant, but it was not universally adopted until the Swedish naturalist, Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) set about methodically classifying and naming the whole of the natural world. The names of plants: In 1753, Linnaeus published his "Species Plantarum". The modern names of nearly all plants date from this work or obey the conventions laid down in it. The scientific name for an organism consists of two words: i) the genus or generic name, ii) the specific epithet. -

International Code of Zoological Nomenclature Adopted by the XV

fetsS WW w»È¥STOPiifliîM «SSII »c»»W»tAaVŒHiWJ ^®{f,!s,)'ffi!îS kîvî*X-v!»J#Ï*>%!•»» Hmtljil «jiRfij mrmu :»;!N\>VS'. W]'■;;} ''.;'-'l|]■■ iï:'ï;llI vl'-'iv;-' H Sifcfe-•*: v:v:;::vv;:';:vv V>|lV.\VO.kvS'vk\ \>y.js. ini&K3«MM©ifnfi* >sv îv.vtvîlPi?>^\sîv-\s\Kv;>^v#i'S®S?:1V:is ';v':::SS!'S 'V.\'\kiv :';$llffe$ fW'É vwln/fr^&V- Sj|;«Siî:8KKîvfihffWtf Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise), without the prior written consent of the publisher and copyright holder. Published by The International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature 1999 c/o The Natural History Museum - Cromwell Road - London SW7 5BD - UK © International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature 1999 Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature INTERNATIONAL CODE OF ZOOLOGICAL NOMENCLATURE Fourth Edition adopted by the International Union ofBiological Sciences The provisions of this Code supersede those of the previous editions with effect from 1 January 2000 'ICZ^Cj ISBN 0 85301 006 4 Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries The author of this Code is the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature Editorial Committee W.D.L.