The Voltage-Controlled Analog Synthesizer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

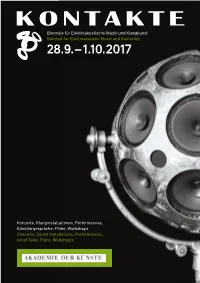

Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops

Biennale für Elektroakustische Musik und Klangkunst Biennial for Electroacoustic Music and Sound Art 28.9. – 1.10.2017 Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops 1 KONTAKTE’17 28.9.–1.10.2017 Biennale für Elektroakustische Musik und Klangkunst Biennial for Electroacoustic Music and Sound Art Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops KONTAKTE '17 INHALT 28. September bis 1. Oktober 2017 Akademie der Künste, Berlin Programmübersicht 9 Ein Festival des Studios für Elektroakustische Musik der Akademie der Künste A festival presented by the Studio for Electro acoustic Music of the Akademie der Künste Konzerte 10 Im Zusammenarbeit mit In collaboration with Installationen 48 Deutsche Gesellschaft für Elektroakustische Musik Berliner Künstlerprogramm des DAAD Forum 58 Universität der Künste Berlin Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler Berlin Technische Universität Berlin Ausstellung 62 Klangzeitort Helmholtz Zentrum Berlin Workshop 64 Ensemble ascolta Musik der Jahrhunderte, Stuttgart Institut für Elektronische Musik und Akustik der Kunstuniversität Graz Laboratorio Nacional de Música Electroacústica Biografien 66 de Cuba singuhr – projekte Partner 88 Heroines of Sound Lebenshilfe Berlin Deutschlandfunk Kultur Lageplan 92 France Culture Karten, Information 94 Studio für Elektroakustische Musik der Akademie der Künste Hanseatenweg 10, 10557 Berlin Fon: +49 (0) 30 200572236 www.adk.de/sem EMail: [email protected] KONTAKTE ’17 www.adk.de/kontakte17 #kontakte17 KONTAKTE’17 Die zwei Jahre, die seit der ersten Ausgabe von KONTAKTE im Jahr 2015 vergangen sind, waren für das Studio für Elektroakustische Musik eine ereignisreiche Zeit. Mitte 2015 erhielt das Studio eine großzügige Sachspende ausgesonderter Studiotechnik der Deut schen Telekom, die nach entsprechenden Planungs und Wartungsarbeiten seit 2016 neue Produktionsmöglichkeiten eröffnet. -

The Rai Studio Di Fonologia (1954–83)

ELECTRONIC MUSIC HISTORY THROUGH THE EVERYDAY: THE RAI STUDIO DI FONOLOGIA (1954–83) Joanna Evelyn Helms A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Andrea F. Bohlman Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter Mark Katz Lee Weisert © 2020 Joanna Evelyn Helms ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joanna Evelyn Helms: Electronic Music History through the Everyday: The RAI Studio di Fonologia (1954–83) (Under the direction of Andrea F. Bohlman) My dissertation analyzes cultural production at the Studio di Fonologia (SdF), an electronic music studio operated by Italian state media network Radiotelevisione Italiana (RAI) in Milan from 1955 to 1983. At the SdF, composers produced music and sound effects for radio dramas, television documentaries, stage and film operas, and musical works for concert audiences. Much research on the SdF centers on the art-music outputs of a select group of internationally prestigious Italian composers (namely Luciano Berio, Bruno Maderna, and Luigi Nono), offering limited windows into the social life, technological everyday, and collaborative discourse that characterized the institution during its nearly three decades of continuous operation. This preference reflects a larger trend within postwar electronic music histories to emphasize the production of a core group of intellectuals—mostly art-music composers—at a few key sites such as Paris, Cologne, and New York. Through close archival reading, I reconstruct the social conditions of work in the SdF, as well as ways in which changes in its output over time reflected changes in institutional priorities at RAI. -

Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

452 ROBYNN STILWELL Joplin, Janis. 'Me and Bobby McGee' (Columbia, 1971) i_ /Mercedes Benz' (Columbia, 1971) 17- Llttle Richard. 'Lucille' (Specialty, 1957) 'Tutti Frutti' (Specialty, 1955) Lynn, Loretta. 'The Pili' (MCA, 1975) Expanding horizons: the International 'You Ain't Woman Enough to Take My Man' (MCA, 1966) avant-garde, 1962-75 'Your Squaw Is On the Warpath' (Decca, 1969) The Marvelettes. 'Picase Mr. Postman' (Motown, 1961) RICHARD TOOP Matchbox Twenty. 'Damn' (Atlantic, 1996) Nelson, Ricky. 'Helio, Mary Lou' (Imperial, 1958) 'Traveling Man' (Imperial, 1959) Phair, Liz. 'Happy'(live, 1996) Darmstadt after Steinecke Pickett, Wilson. 'In the Midnight Hour' (Atlantic, 1965) Presley, Elvis. 'Hound Dog' (RCA, 1956) When Wolfgang Steinecke - the originator of the Darmstadt Ferienkurse - The Ravens. 'Rock All Night Long' (Mercury, 1948) died at the end of 1961, much of the increasingly fragüe spirit of collegial- Redding, Otis. 'Dock of the Bay' (Stax, 1968) ity within the Cologne/Darmstadt-centred avant-garde died with him. Boulez 'Mr. Pitiful' (Stax, 1964) and Stockhausen in particular were already fiercely competitive, and when in 'Respect'(Stax, 1965) 1960 Steinecke had assigned direction of the Darmstadt composition course Simón and Garfunkel. 'A Simple Desultory Philippic' (Columbia, 1967) to Boulez, Stockhausen had pointedly stayed away.1 Cage's work and sig- Sinatra, Frank. In the Wee SmallHoun (Capítol, 1954) Songsfor Swinging Lovers (Capítol, 1955) nificance was a constant source of acrimonious debate, and Nono's bitter Surfaris. 'Wipe Out' (Decca, 1963) opposition to himz was one reason for the Italian composer being marginal- The Temptations. 'Papa Was a Rolling Stone' (Motown, 1972) ized by the Cologne inner circle as a structuralist reactionary. -

Ambiant Creativity Mo Fr Workshop Concerts Lectures Discussions

workshop concerts lectures discussions ambiant creativity »digital composition« March 14-18 2011 mo fr jérôme bertholon sebastian berweck ludger brümmer claude cadoz omer chatziserif johannes kreidler damian marhulets thomas a. troge iannis zannos // program thursday, march 17th digital creativity 6 pm, Lecture // Caught in the Middle: The Interpreter in the Digital Age and Sebastian Berweck contemporary ZKM_Vortragssaal music 6.45 pm, IMA | lab // National Styles in Electro- acoustic Music? thomas a. troged- Stipends of “Ambiant Creativity” and Sebastian fdfd Berweck ZKM_Vortragssaal 8 pm, Concert // Interactive Creativity with Sebastian Berweck (Pianist, Performer), works by Ludger Brümmer, Johannes Kreidler, Enno Poppe, Terry Riley, Giacinto Scelsi ZKM_Kubus friday, march 18th 6 pm, Lecture // New Technologies and Musical Creations Johannes Kreidler ZKM_Vortragsaal 6.45 pm, Round Table // What to Expect? Hopes and Problems of Technological Driven Art Ludger Brümmer, Claude Cadoz, Johannes Kreidler, Thomas A. Troge, Iannis Zannos ZKM_Vortragssaal 8 pm, Concert // Spatial Creativity, works by Jérôme Bertholon, Ludger Brümmer, Claude Cadoz, Omer Chatziserif, Damian Marhulets, Iannis Zannos ZKM_Kubus 10pm, Night Concert // Audiovisual Creativity with audiovisual compositions and dj- sets by dj deepthought and Damian Marhulets ZKM_Musikbalkon // the project “ambiant creativity” The “Ambiant Creativity” project aims to promote the potential of interdisciplinary coopera- tion in the arts with modern technology, and its relevance at the European Level. The results and events are opened to the general public. The project is a European Project funded with support from the European Commission under the Culture Program. It started on October, 2009 for a duration of two years. The partnership groups ACROE in France, ZKM | Karlsruhe in Germany and the Ionian University in Greece. -

Latin American Nimes: Electronic Musical Instruments and Experimental Sound Devices in the Twentieth Century

Latin American NIMEs: Electronic Musical Instruments and Experimental Sound Devices in the Twentieth Century Martín Matus Lerner Desarrollos Tecnológicos Aplicados a las Artes EUdA, Universidad Nacional de Quilmes Buenos Aires, Argentina [email protected] ABSTRACT 2. EARLY EXPERIENCES During the twentieth century several Latin American nations 2.1 The singing arc in Argentina (such as Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Cuba and Mexico) have In 1900 William du Bois Duddell publishes an article in which originated relevant antecedents in the NIME field. Their describes his experiments with “the singing arc”, one of the first innovative authors have interrelated musical composition, electroacoustic musical instruments. Based on the carbon arc lutherie, electronics and computing. This paper provides a lamp (in common use until the appearance of the electric light panoramic view of their original electronic instruments and bulb), the singing or speaking arc produces a high volume buzz experimental sound practices, as well as a perspective of them which can be modulated by means of a variable resistor or a regarding other inventions around the World. microphone [35]. Its functioning principle is present in later technologies such as plasma loudspeakers and microphones. Author Keywords In 1909 German physicist Emil Bose assumes direction of the Latin America, music and technology history, synthesizer, drawn High School of Physics at the Universidad de La Plata. Within sound, luthería electrónica. two years Bose turns this institution into a first-rate Department of Physics (pioneer in South America). On March 29th 1911 CCS Concepts Bose presents the speaking arc at a science event motivated by the purchase of equipment and scientific instruments from the • Applied computing → Sound and music German company Max Kohl. -

Scambi Fushi Tarazu: a Musical Representation of a Drosophila Gene Expression Pattern

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 4 January 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202001.0026.v1 Scambi fushi tarazu: A Musical Representation of a Drosophila Gene Expression Pattern Derek Gatherer Division of Biomedical & Life Sciences Lancaster University Lancaster LA1 4YW, UK [email protected] Abstract: The term Bio-Art has entered common usage to describe the interaction between the arts and the biological sciences. Although Bio-Art implies that Bio-Music would be one of its obvious sub- disciplines, the latter term has been much less frequently used. Nevertheless, there has been no shortage of projects that have brought together music and the biological sciences. Most of these projects have allowed the biological data to dictate to a large extent the sound produced, for instance the translation of genome or protein sequences into musical phrases, and therefore may be regarded as process compositions. Here I describe a Bio-Music process composition that derives its biological input from a visual representation of the expression pattern of the gene fushi tarazu in the Drosophila embryo. An equivalent pattern is constructed from the Scambi portfolio of short electronic music fragments created by Henri Pousseur in the 1950s. This general form of the resulting electronic composition follows that of the fushi tarazu pattern, while satisfying the rules of the Scambi compositional framework devised by Pousseur. The range and flexibility of Scambi make it ideally suited to other Bio-Music projects wherever there is a requirement, or desire, to build larger sonic structures from small units. Keywords: Scambi; fushi tarazu; Drosophila; BioArt; BioMusic; Music; process composition 1 © 2020 by the author(s). -

Sprechen Über Neue Musik

Sprechen über Neue Musik Eine Analyse der Sekundärliteratur und Komponistenkommentare zu Pierre Boulez’ Le Marteau sans maître (1954), Karlheinz Stockhausens Gesang der Jünglinge (1956) und György Ligetis Atmosphères (1961) Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt der Philosophischen Fakultät II der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Institut für Musik, Abteilung Musikwissenschaft von Julia Heimerdinger ∗∗∗ Datum der Verteidigung 4. Juli 2013 Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Auhagen Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Hirschmann I Inhalt 1. Einleitung 1 2. Untersuchungsgegenstand und Methode 10 2.1. Textkorpora 10 2.2. Methode 12 2.2.1. Problemstellung und das Programm MAXQDA 12 2.2.2. Die Variablentabelle und die Liste der Codes 15 2.2.3. Auswertung: Analysefunktionen und Visual Tools 32 3. Pierre Boulez: Le Marteau sans maître (1954) 35 3.1. „Das Glück einer irrationalen Dimension“. Pierre Boulez’ Werkkommentare 35 3.2. Die Rätsel des Marteau sans maître 47 3.2.1. Die auffällige Sprache zu Le Marteau sans maître 58 3.2.2. Wahrnehmung und Interpretation 68 4. Karlheinz Stockhausen: Gesang der Jünglinge (elektronische Musik) (1955-1956) 85 4.1. Kontinuum. Stockhausens Werkkommentare 85 4.2. Kontinuum? Gesang der Jünglinge 95 4.2.1. Die auffällige Sprache zum Gesang der Jünglinge 101 4.2.2. Wahrnehmung und Interpretation 109 5. György Ligeti: Atmosphères (1961) 123 5.1. Von der musikalischen Vorstellung zum musikalischen Schein. Ligetis Werkkommentare 123 5.1.2. Ligetis auffällige Sprache 129 5.1.3. Wahrnehmung und Interpretation 134 5.2. Die große Vorstellung. Atmosphères 143 5.2.2. Die auffällige Sprache zu Atmosphères 155 5.2.3. -

5. Iannis Xenakis

5. Iannis Xenakis „C’était deux ou trois ans après l’invasion russe en Tchécoslovaquie. Je suis tombé amoreux de la musique de Varèse et de Xenakis. Je me demande pourquoi […].“ Milan Kundera: Une rencontre129 Recepce a teoretická reflexe tvorby Iannise Xenakise v našem prostředí není nijak významná. Když pomineme texty a studie, které jsou součástí lexik, vysokoškolských skript a obecných přehledů dějin hudby, stojí za zmínku především stať Milana Kundery Iannis Xenakis, prorok necitovosti. Ačkoliv se nejedná o muzikologickou studii, jejímu autorovi se (jako mnohokrát) daří popsat konkrétní rysy skladatelovy tvorby s daleko větší přesností, než jaké by byl zřejmě schopen muzikolog. Ve francouzské verzi se text objevuje v roce 1980 pod názvem Le refus intégral de l’héritage ou Iannis Xenakis (Naprosté odmítnutí dědictví aneb Iannis Xenakis). O to cennější je skutečnost, že se Kundera k původnímu textu vrací v nově vydané sbírce esejů Une rencontre. Přiznává v něm, že v hudbě Varèse a Xenakise nalezl zvláštní útěchu, která spočívá ve smíření s nevyhnutelností konečnosti. Prorokem necitovosti nazval Carl Gustav Jung Jamese Joyce ve své analýze Odyssea. Zde také přichází s tezí, že citovost je nadstavbou brutality. Vyvážení této sentimentality přinášejí proroci asentimentality, podle Junga Joyce, podle Kundery Xenakis. Podle Kundery hudba vždy svojí subjektivitou čelila objektivitě světa. Existují však okamžiky, kdy se subjektivita nebo také emocionalita (která za normálních okolností vrací člověka k jeho podstatě a zmírňuje chlad intelektu) stává nástrojem brutality a zla. V takových okamžicích se naopak objektivní hudba stává krásou, která smývá nánosy emocionality a tlumí barbarství sentimentu. Xenakisův postoj k historii hudby je podle Kundery radikálně odmítavý. -

Storia E Analisi Della Musica Elettronica

Storia e analisi della Musica Elettronica (Biennio di Musicologia) crediti ?? 36 h, lezioni frontali collettive con ascolti ed esercitazioni Programma d’esame La musica che fa uso di tecnologie legate all’elettricità ha creato nel corso di questo ultimo secolo un repertorio che fonde insieme problematiche musicali (compositive e interpretative) e riflessioni scientifiche-epistemologiche; indagare queste relazioni si mostra essenziale per il compositore e l’interprete dei musica elettro-acustica. Introduzione: riepilogodelle principali tendenze e protagonisti della musica del ‘900 I primi esempi di musica con tecnologie elettriche/elettroniche: Musique concrète, Musica elettronica pura, Tape music, Musica elettroacustica, Musica acusmatica, Musica sperimentale. Gli studi di musica elettronica analogica degli anni '50, le tecniche compositive, i sistemi di notazione, le prassi esecutive. Lo studio di Fonologia Musicale della Rai di Milano. Caratteristiche generali della musica elettroacustica degli anni '60. Analisi e ascolti di uno o più estratti di un'opera degli anni '50 tratti fra i seguenti: Pierre Schaeffer, Cinq études de bruits (1948) John Cage, Imaginary Landscape n. 5 (1952) Karlheinz Stockhausen, Studie I (1953) Karlheinz Stockhausen, Studie II (1954) Karlheinz Stockhausen, Gesang der Jünglinge (1955-56) György Ligeti, Glissandi (1957) Henri Pousseur, Scambi (1957) Franco Evangelisti, Incontri di fasce sonore (1957) Luciano Berio, Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) (1958) John Cage, Fontana Mix (1958) György Ligeti, Artikulation (1958) -

Active Preservation of Electrophone Musical Instruments

ACTIVE PRESERVATION OF ELECTROPHONE MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS. THE CASE OF THE “LIETTIZZATORE” OF “STUDIO DI FONOLOGIA MUSICALE” (RAI, MILANO) Sergio Canazza, Federico Avanzini Antonio Roda` SMC Group, Dept. of Information Engineering Maria Maddalena Novati AVIRES Lab., Dept. of Informatics University of Padova RAI, Milano Viale delle Scienze, Udine Via Gradenigo 6/B, 35131 Padova Archivio di Fonologia University of Udine [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT installation consisting of a SW-HW system that re-creates the electronic lutherie of the Studio, allowing users to in- This paper presents first results of an ongoing project de- teract with such lutherie. In particular, the production setup voted to the analysis and virtualization of the analog elec- originally employed to compose Scambi is considered as a tronic devices of the “Studio di Fonologia Musicale”, one relevant case study. Achieving the goal of the project im- of the European centres of reference for the production of plies (i) analyzing the original devices through both project electroacoustic music in the 1950’s and 1960’s. After a schemes and direct inspection; (ii) validating the analysis brief summary of the history of the Studio, the paper dis- through simulations with ad-hoc tools (particularly Spice cusses a particularly representative musical work produced – Simulation Program with Integrated Circuit Emphasis, a at the Studio, Scambi by Henri Pousseur, and it presents software especially designed to simulate analog electronic initial results on the analysis and simulation of the elec- circuits [3]); (iii) developing physical models of the analog tronic device used by Pousseur in this composition, and the devices, which allow efficient simulation of their function- ongoing work finalized at developing an installation that ing (according to the virtual analog paradigm [4]); (iv) de- re-creates such electronic lutherie. -

Holmes Electronic and Experimental Music

C H A P T E R 2 Early Electronic Music in Europe I noticed without surprise by recording the noise of things that one could perceive beyond sounds, the daily metaphors that they suggest to us. —Pierre Schaeffer Before the Tape Recorder Musique Concrète in France L’Objet Sonore—The Sound Object Origins of Musique Concrète Listen: Early Electronic Music in Europe Elektronische Musik in Germany Stockhausen’s Early Work Other Early European Studios Innovation: Electronic Music Equipment of the Studio di Fonologia Musicale (Milan, c.1960) Summary Milestones: Early Electronic Music of Europe Plate 2.1 Pierre Schaeffer operating the Pupitre d’espace (1951), the four rings of which could be used during a live performance to control the spatial distribution of electronically produced sounds using two front channels: one channel in the rear, and one overhead. (1951 © Ina/Maurice Lecardent, Ina GRM Archives) 42 EARLY HISTORY – PREDECESSORS AND PIONEERS A convergence of new technologies and a general cultural backlash against Old World arts and values made conditions favorable for the rise of electronic music in the years following World War II. Musical ideas that met with punishing repression and indiffer- ence prior to the war became less odious to a new generation of listeners who embraced futuristic advances of the atomic age. Prior to World War II, electronic music was anchored down by a reliance on live performance. Only a few composers—Varèse and Cage among them—anticipated the importance of the recording medium to the growth of electronic music. This chapter traces a technological transition from the turntable to the magnetic tape recorder as well as the transformation of electronic music from a medium of live performance to that of recorded media. -

Electroacoustic Music Studios BEAST Concerts in 1994

Electroacoustic Music Studios BEAST Concerts in 1994 Norwich, 7th February Manchester, 22nd February Nottingham, 18th March More about BEAST concerts:- The Acousmatic Experience, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 7th - 10th April Concert news Edinburgh, Scotland, 17th May Concert archives London, 11th November Birmingham, 13th November Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival, Huddersfield, 18th November Rumours, Birmingham, England, 4th - 5th December 7th February 1994 Norwich, England Sound diffusion for the Sonic Arts Network 22nd February 1994 Manchester, England Sound diffusion for the Sonic Arts Network 18th March 1994 Nottingham, England Sound diffusion for the Sonic Arts Network The Acousmatic Experience, 7th - 10th April 1994 Amsterdam, The Netherlands A series of concerts performed by BEAST. 7th April 8.15 pm Karlheinz Stockhausen - Hymnen 8th April 8.15 pm 1. Yves Daoust - Suite Baroque: toccata 2. Jonty Harrison - Pair/Impair 3. Yves Daoust - Suite Baroque: "Qu'ai-je entendu" 4. Kees Tazelaar - Paradigma 5. Yves Daoust - Suite Baroque: "Les Agrémants" 6. Barry Truax - Basilica 7. Yves Daoust - Suite Baroque: "L'Extase" 8. Denis Smalley - Wind Chimes 9th April 2 pm 1. Barry Truax - The Blind Man 2. Bernard Parmegiani - Dedans/Dehors 3. Francis Dhomont - Espace/Escape 4. Jan Boerman - Composition 1972 8.15 pm 1. Michel Chion - Requiem 2. Robert Normandeau - Mémoires Vives 3. Bernard Parmegiani - Rouge-Mort: Thanatos 4. Erik M. Karlsson - La Disparition de l'Azur 10th April 2 pm 1. Pierre Schaeffer & Pierre Henry - Synphonie Pour un Homme Seul 2. John Oswald - Plunderphonics [extract] 3. Carl Stone - Hop Ken 4. Mark Wingate - Ode to the South-Facing Form 5. Erik M. Karlsson - Anchoring Arrows 8 pm 1.