A History of Electronic Music Pioneers David Dunn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

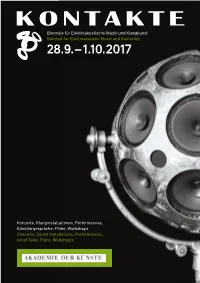

Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops

Biennale für Elektroakustische Musik und Klangkunst Biennial for Electroacoustic Music and Sound Art 28.9. – 1.10.2017 Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops 1 KONTAKTE’17 28.9.–1.10.2017 Biennale für Elektroakustische Musik und Klangkunst Biennial for Electroacoustic Music and Sound Art Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops KONTAKTE '17 INHALT 28. September bis 1. Oktober 2017 Akademie der Künste, Berlin Programmübersicht 9 Ein Festival des Studios für Elektroakustische Musik der Akademie der Künste A festival presented by the Studio for Electro acoustic Music of the Akademie der Künste Konzerte 10 Im Zusammenarbeit mit In collaboration with Installationen 48 Deutsche Gesellschaft für Elektroakustische Musik Berliner Künstlerprogramm des DAAD Forum 58 Universität der Künste Berlin Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler Berlin Technische Universität Berlin Ausstellung 62 Klangzeitort Helmholtz Zentrum Berlin Workshop 64 Ensemble ascolta Musik der Jahrhunderte, Stuttgart Institut für Elektronische Musik und Akustik der Kunstuniversität Graz Laboratorio Nacional de Música Electroacústica Biografien 66 de Cuba singuhr – projekte Partner 88 Heroines of Sound Lebenshilfe Berlin Deutschlandfunk Kultur Lageplan 92 France Culture Karten, Information 94 Studio für Elektroakustische Musik der Akademie der Künste Hanseatenweg 10, 10557 Berlin Fon: +49 (0) 30 200572236 www.adk.de/sem EMail: [email protected] KONTAKTE ’17 www.adk.de/kontakte17 #kontakte17 KONTAKTE’17 Die zwei Jahre, die seit der ersten Ausgabe von KONTAKTE im Jahr 2015 vergangen sind, waren für das Studio für Elektroakustische Musik eine ereignisreiche Zeit. Mitte 2015 erhielt das Studio eine großzügige Sachspende ausgesonderter Studiotechnik der Deut schen Telekom, die nach entsprechenden Planungs und Wartungsarbeiten seit 2016 neue Produktionsmöglichkeiten eröffnet. -

On the Question of the Baroque Instrumental Concerto Typology

Musica Iagellonica 2012 ISSN 1233-9679 Piotr WILK (Kraków) On the question of the Baroque instrumental concerto typology A concerto was one of the most important genres of instrumental music in the Baroque period. The composers who contributed to the development of this musical genre have significantly influenced the shape of the orchestral tex- ture and created a model of the relationship between a soloist and an orchestra, which is still in use today. In terms of its form and style, the Baroque concerto is much more varied than a concerto in any other period in the music history. This diversity and ingenious approaches are causing many challenges that the researches of the genre are bound to face. In this article, I will attempt to re- view existing classifications of the Baroque concerto, and introduce my own typology, which I believe, will facilitate more accurate and clearer description of the content of historical sources. When thinking of the Baroque concerto today, usually three types of genre come to mind: solo concerto, concerto grosso and orchestral concerto. Such classification was first introduced by Manfred Bukofzer in his definitive monograph Music in the Baroque Era. 1 While agreeing with Arnold Schering’s pioneering typology where the author identifies solo concerto, concerto grosso and sinfonia-concerto in the Baroque, Bukofzer notes that the last term is mis- 1 M. Bukofzer, Music in the Baroque Era. From Monteverdi to Bach, New York 1947: 318– –319. 83 Piotr Wilk leading, and that for works where a soloist is not called for, the term ‘orchestral concerto’ should rather be used. -

Delia Derbyshire

www.delia-derbyshire.org Delia Derbyshire Delia Derbyshire was born in Coventry, England, in 1937. Educated at Coventry Grammar School and Girton College, Cambridge, where she was awarded a degree in mathematics and music. In 1959, on approaching Decca records, Delia was told that the company DID NOT employ women in their recording studios, so she went to work for the UN in Geneva before returning to London to work for music publishers Boosey & Hawkes. In 1960 Delia joined the BBC as a trainee studio manager. She excelled in this field, but when it became apparent that the fledgling Radiophonic Workshop was under the same operational umbrella, she asked for an attachment there - an unheard of request, but one which was, nonetheless, granted. Delia remained 'temporarily attached' for years, regularly deputising for the Head, and influencing many of her trainee colleagues. To begin with Delia thought she had found her own private paradise where she could combine her interests in the theory and perception of sound; modes and tunings, and the communication of moods using purely electronic sources. Within a matter of months she had created her recording of Ron Grainer's Doctor Who theme, one of the most famous and instantly recognisable TV themes ever. On first hearing it Grainer was tickled pink: "Did I really write this?" he asked. "Most of it," replied Derbyshire. Thus began what is still referred to as the Golden Age of the Radiophonic Workshop. Initially set up as a service department for Radio Drama, it had always been run by someone with a drama background. -

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

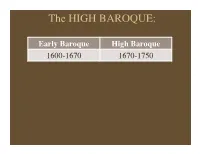

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

Gardner • Even Orpheus Needs a Synthi Edit No Proof

James Gardner Even Orpheus Needs a Synthi Since his return to active service a few years ago1, Peter Zinovieff has appeared quite frequently in interviews in the mainstream press and online outlets2 talking not only about his recent sonic art projects but also about the work he did in the 1960s and 70s at his own pioneering computer electronic music studio in Putney. And no such interview would be complete without referring to EMS, the synthesiser company he co-founded in 1969, or namechecking the many rock celebrities who used its products, such as the VCS3 and Synthi AKS synthesisers. Before this Indian summer (he is now 82) there had been a gap of some 30 years in his compositional activity since the demise of his studio. I say ‘compositional’ activity, but in the 60s and 70s he saw himself as more animateur than composer and it is perhaps in that capacity that his unique contribution to British electronic music during those two decades is best understood. In this article I will discuss just some of the work that was done at Zinovieff’s studio during its relatively brief existence and consider two recent contributions to the documentation and contextualization of that work: Tom Hall’s chapter3 on Harrison Birtwistle’s electronic music collaborations with Zinovieff; and the double CD Electronic Calendar: The EMS Tapes,4 which presents a substantial sampling of the studio’s output between 1966 and 1979. Electronic Calendar, a handsome package to be sure, consists of two CDs and a lavishly-illustrated booklet with lengthy texts. -

Interpretação Em Tempo Real Sobre Material Sonoro Pré-Gravado

Interpretação em tempo real sobre material sonoro pré-gravado JOÃO PEDRO MARTINS MEALHA DOS SANTOS Mestrado em Multimédia da Universidade do Porto Dissertação realizada sob a orientação do Professor José Alberto Gomes da Universidade Católica Portuguesa - Escola das Artes Julho de 2014 2 Agradecimentos Em primeiro lugar quero agradecer aos meus pais, por todo o apoio e ajuda desde sempre. Ao orientador José Alberto Gomes, um agradecimento muito especial por toda a paciência e ajuda prestada nesta dissertação. Pelo apoio, incentivo, e ajuda à Sara Esteves, Inês Santos, Manuel Molarinho, Carlos Casaleiro, Luís Salgado e todos os outros amigos que apesar de se encontraram fisicamente ausentes, estão sempre presentes. A todos, muito obrigado! 3 Resumo Esta dissertação tem como foco principal a abordagem à interpretação em tempo real sobre material sonoro pré-gravado, num contexto performativo. Neste caso particular, material sonoro é entendido como música, que consiste numa pulsação regular e definida. O objetivo desta investigação é compreender os diferentes modelos de organização referentes a esse material e, consequentemente, apresentar uma solução em forma de uma aplicação orientada para a performance ao vivo intitulada Reap. Importa referir que o material sonoro utilizado no software aqui apresentado é composto por músicas inteiras, em oposição às pequenas amostras (samples) recorrentes em muitas aplicações já existentes. No desenvolvimento da aplicação foi adotada a análise estatística de descritores aplicada ao material sonoro pré-gravado, de maneira a retirar segmentos que permitem uma nova reorganização da informação sequencial originalmente contida numa música. Através da utilização de controladores de matriz com feedback visual, o arranjo e distribuição destes segmentos são alterados e reorganizados de forma mais simplificada. -

Music 80C History and Literature of Electronic Music Tuesday/Thursday, 1-4PM Music Center 131

Music 80C History and Literature of Electronic Music Tuesday/Thursday, 1-4PM Music Center 131 Instructor: Madison Heying Email: [email protected] Office Hours: By Appointment Course Description: This course is a survey of the history and literature of electronic music. In each class we will learn about a music-making technique, composer, aesthetic movement, and the associated repertoire. Tests and Quizzes: There will be one test for this course. Students will be tested on the required listening and materials covered in lectures. To be prepared students must spend time outside class listening to required listening, and should keep track of the content of the lectures to study. Assignments and Participation: A portion of each class will be spent learning the techniques of electronic and computer music-making. Your attendance and participation in this portion of the class is imperative, since you will not necessarily be tested on the material that you learn. However, participation in the assignments and workshops will help you on the test and will provide you with some of the skills and context for your final projects. Assignment 1: Listening Assignment (Due June 30th) Assignment 2: Field Recording (Due July 12th) Final Project: The final project is the most important aspect of this course. The following descriptions are intentionally open-ended so that you can pursue a project that is of interest to you; however, it is imperative that your project must be connected to the materials discussed in class. You must do a 10-20 minute in class presentation of your project. You must meet with me at least once to discuss your paper and submit a ½ page proposal for your project. -

Musical Intelligences and Human Instruments in Science Fiction and Film

SINGING MACHINES: MUSICAL INTELLIGENCES AND HUMAN INSTRUMENTS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FILM by Nicholas Christian Laudadio October 8, 2004 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The State University of New York at Buffalo in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Copyright by Nicholas Christian Laudadio 2004 ii Sincerely felt and appropriately formatted thanks to: My committee members: Joseph Conte (director), James Bono, James Bunn (with tremendous help along the way from Charles Bernstein and Chip Delaney) My outside reader: Bernadette Wegenstein My parents And most certainly to Meghan Sweeney, without whom all goes poof, &c. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Setting the Mood Organ: An Introduction 1 CHAPTER ONE The Song of Last Words: Kubrick’s 2001 and the Acoustic Moment of Disconnection 13 CHAPTER TWO Just Like So But Isn’t: Listening AIs, Recursive Disconnection, and Richard Powers’s Galatea 2.2 56 CHAPTER THREE Instrumentes of Musyk: An Organological Approach to Lloyd Biggle Jr.’s “The Tunesmith” 93 CHAPTER FOUR What Dreams Sound Like: Forbidden Planet and a Material History of the Electronic Musical Instrument 135 WORKS CITED 179 iv ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1: Frank Poole Jogging in the Ship from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey 22 Figure 2: Frank and Dave Discuss HAL’s Fate from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey 41 Figure 3: HAL Disconnected from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey 47 Figure 4: “The Organist and His Wife” by Israel Van Meckenem 94 Figure 5: The Telharmonium from “120 Years of Electronic Musical Instruments” 145 Figure 6: Clara Rockmore 151 Figure 7: Raymond Scott and his Family from Gert-Jan Blom’s Manhattan Research, Inc. -

Vector Synthesis: a Media Archaeological Investigation Into Sound-Modulated Light

VECTOR SYNTHESIS: A MEDIA ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION INTO SOUND-MODULATED LIGHT Submitted for the qualification Master of Arts in Sound in New Media, Department of Media, Aalto University, Helsinki FI April, 2019 Supervisor: Antti Ikonen Advisor: Marco Donnarumma DEREK HOLZER [BLANK PAGE] Aalto University, P.O. BOX 11000, 00076 AALTO www.aalto.fi Master of Arts thesis abstract Author Derek Holzer Title of thesis Vector Synthesis: a Media-Archaeological Investigation into Sound-Modulated Light Department Department of Media Degree programme Sound in New Media Year 2019 Number of pages 121 Language English Abstract Vector Synthesis is a computational art project inspired by theories of media archaeology, by the history of computer and video art, and by the use of discarded and obsolete technologies such as the Cathode Ray Tube monitor. This text explores the military and techno-scientific legacies at the birth of modern computing, and charts attempts by artists of the subsequent two decades to decouple these tools from their destructive origins. Using this history as a basis, the author then describes a media archaeological, real time performance system using audio synthesis and vector graphics display techniques to investigate direct, synesthetic relationships between sound and image. Key to this system, realized in the Pure Data programming environment, is a didactic, open source approach which encourages reuse and modification by other artists within the experimental audiovisual arts community. Keywords media art, media-archaeology, audiovisual performance, open source code, cathode- ray tubes, obsolete technology, synesthesia, vector graphics, audio synthesis, video art [BLANK PAGE] O22 ABSTRACT Vector Synthesis is a computational art project inspired by theories of media archaeology, by the history of computer and video art, and by the use of discarded and obsolete technologies such as the Cathode Ray Tube monitor. -

Computer Music

THE OXFORD HANDBOOK OF COMPUTER MUSIC Edited by ROGER T. DEAN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2009 by Oxford University Press, Inc. First published as an Oxford University Press paperback ion Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Oxford handbook of computer music / edited by Roger T. Dean. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-979103-0 (alk. paper) i. Computer music—History and criticism. I. Dean, R. T. MI T 1.80.09 1009 i 1008046594 789.99 OXF tin Printed in the United Stares of America on acid-free paper CHAPTER 12 SENSOR-BASED MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS AND INTERACTIVE MUSIC ATAU TANAKA MUSICIANS, composers, and instrument builders have been fascinated by the expres- sive potential of electrical and electronic technologies since the advent of electricity itself. -

S P O È Me E Lectronique

Densil Cabrera S o u n d S p a c e a n d E d g a r d V a r è s e ’ s P o è m e E l e c t r o n i q u e Master of Arts 1994 University of Technology, Sydney C E R T I F I C A T E I certify that this thesis has not already been submitted for any degree and is not being submitted as part of candidature for any other degree. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me and that any help that I have received in preparing this thesis, and all sources used, have been acknowledged in this thesis. Signature of Candidate i A c k n o w l e d g m e n t s The author acknowledges the specific assistance of the following people in the preparation of this thesis: Martin Harrison for supervision; Greg Schiemer for support in the early stages of research; Elizabeth Francis and Peter Keller for allowing the use of facilities at the University of New South Wales’ Infant Research Centre for the production of the Appendix; Joe Wolfe and Emery Schubert; Roberta Lukes for her correspondence; Kirsten Harley and Greg Walkerden for proof reading. The author also acknowledges an award from the University of Technology, Sydney Vice- Chancellor’s Postgraduate Student Conference Fund in 1992. ii T a b l e o f C o n t e n t s I n t r o d u c t i o n The Philips Pavilion and Poème Electronique Approaches C h a p t e r 1 - S o u n d i n t h e W a l l s Architecture, Music: A Lineage Music-Architecture: Hyperbolic Paraboloids Crystal Sculpture Domestic Images of Sound in Space Sound, Space, Surface C h a p t e r 2 - H y p e r b o l i c P a r a b o l o i d s A -

XENAKIS AS a SOUND SCULPTOR Makis Solomos

XENAKIS AS A SOUND SCULPTOR Makis Solomos To cite this version: Makis Solomos. XENAKIS AS A SOUND SCULPTOR. in welt@musik - Musik interkulturell, publi- cations de l’Institut für Neue Musik und Musikerziehung Darmstadt, volume 44, Mainz, Schott, 2004„ p. 161-169, 2004. hal-01202904 HAL Id: hal-01202904 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01202904 Submitted on 21 Sep 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 XENAKIS AS A SOUND SCULPTOR* Makis Solomos Abstract One of the main revolutions —and maybe the most important one— of twentieth century music is the emergence of sound. From Debussy to recent contemporary music, from rock’n’roll to electronica, the history of music has progressively and to some extent focused on the very foundation of music: sound. During this history —when, in some way, composition of sound takes the place of composition with sounds—, Xenakis plays a major role. Already from the 1950s, with orchestral pieces like Metastaseis (1953-54) or Pithoprakta (1955-56) and with electronic pieces like Diamorphoses (1957) or Concret PH (1958), he develops the idea of composition as composition-of-sound to such an extent that, if the expression was not already used for designating a new interdisciplinary artistic activity, we could characterize him as a “sound sculptor”.