History, Second World War E-Mail [email protected] Declaration of Interests No Conflict of Interests Declared

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

John Curtin's War

backroom briefings John Curtin's war CLEM LLOYD & RICHARD HALL backroom briefings John Curtin's WAR edited by CLEM LLOYD & RICHARD HALL from original notes compiled by Frederick T. Smith National Library of Australia Canberra 1997 Front cover: Montage of photographs of John Curtin, Prime Minister of Australia, 1941-45, and of Old Parliament House, Canberra Photographs from the National Library's Pictorial Collection Back cover: Caricature of John Curtin by Dubois Bulletin, 8 October 1941 Published by the National Library of Australia Canberra ACT 2600 © National Library of Australia 1997 Introduction and annotations © Clem Lloyd and Richard Hall Every reasonable endeavour has been made to contact relevant copyright holders of illustrative material. Where this has not proved possible, the copyright holders are invited to contact the publisher. National Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data Backroom briefings: John Curtin's war. Includes index. ISBN 0 642 10688 6. 1. Curtin, John, 1885-1945. 2. World War, 1939-1945— Press coverage—Australia. 3. Journalism—Australia. I. Smith, FT. (Frederick T.). II. Lloyd, C.J. (Clement John), 1939- . III. Hall, Richard, 1937- . 940.5394 Editor: Julie Stokes Designer: Beverly Swifte Picture researcher/proofreader: Tony Twining Printed by Goanna Print, Canberra Published with the assistance of the Lloyd Ross Forum CONTENTS Fred Smith and the secret briefings 1 John Curtin's war 12 Acknowledgements 38 Highly confidential: press briefings, June 1942-January 1945 39 Introduction by F.T. Smith 40 Chronology of events; Briefings 42 Index 242 rederick Thomas Smith was born in Balmain, Sydney, Fon 18 December 1904, one of a family of two brothers and two sisters. -

Members of Parliament Disqualified Since 1900 This Document Provides Information About Members of Parliament Who Have Been Disqu

Members of Parliament Disqualified since 1900 This document provides information about Members of Parliament who have been disqualified since 1900. It is impossible to provide an entirely exhaustive list, as in many cases, the disqualification of a Member is not directly recorded in the Journal. For example, in the case of Members being appointed 5 to an office of profit under the Crown, it has only recently become practice to record the appointment of a Member to such an office in the Journal. Prior to this, disqualification can only be inferred from the writ moved for the resulting by-election. It is possible that in some circumstances, an election could have occurred before the writ was moved, in which case there would be no record from which to infer the disqualification, however this is likely to have been a rare occurrence. This list is based on 10 the writs issued following disqualification and the reason given, such as appointments to an office of profit under the Crown; appointments to judicial office; election court rulings and expulsion. Appointment of a Member to an office of profit under the Crown in the Chiltern Hundreds or the Manor of Northstead is a device used to allow Members to resign their seats, as it is not possible to simply resign as a Member of Parliament, once elected. This is by far the most common means of 15 disqualification. There are a number of Members disqualified in the early part of the twentieth century for taking up Ministerial Office. Until the passage of the Re-Election of Ministers Act 1919, Members appointed to Ministerial Offices were disqualified and had to seek re-election. -

Oxford, 1984); H

Notes Notes to the Introduction I. K. O. Morgan, Labour in Power, 194~1951 (Oxford, 1984); H. Pelling, The Labour Governments, 194~51 (London, 1984); A. Cairncross, Years of Recovery: British Economic Policy, 194~51 (London, 1985); P. Hen nessy, Never Again: Britain, 194~1951 (London, 1992). 2. J. Saville, The Labour Movement in Britain (London, 1988); J. Fyrth (ed.), Labour's High Noon: The Government and the Economy, 194~51 (London, 1993). 3. C. Barnett, The Audit oj War: The Illusion and Reality of Britain as a Great Nation (London, 1986); The Lost Victory: British Dreams, British Realities, 194~1950 (London, 1995). 4. Symposium, 'Britain's Postwar Industrial Decline', Contemporary Record, 1: 2 (1987), pp. 11-19; N. Tiratsoo (ed.), The Altlee Years (London, 1991). 5. J. Tomlinson, 'Welfare and the Economy: The Economic Impact of the Welfare State, 1945-1951', Twentieth-Century British History, 6: 2 (1995), pp. 194--219. 6. Hennessy, Never Again, p. 453. See also M. Francis, 'Economics and Ethics: the Nature of Labour's Socialism, 1945-1951', Twentieth Century British History, 6: 2 (1995), pp. 220--43. 7. S. Fielding, P. Thompson and N. Tiratsoo, 'England Arise!' The Labour Party and Popular Politics in 1940s Britain (Manchester, 1995), pp. 209- 18. 8. P. Kellner, 'It Wasn't All Right,Jack', Sunday Times, 4 April 1993. See also The Guardian, 9 September 1993. 9. For a summary of the claims made by the political parties, see J. Barnes and A. Seldon, '1951-64: 13 W asted Years?', Contemporary Record, 1: 2 (1987). 10. V. Bogdanor and R. -

Parliamentary Private Secretaries to Prime Ministers Since 1906 Prime Minister Parliamentary Private Secretary Notes

BRIEFING PAPER Number 06579, 11 March 2020 Parliamentary Private Compiled by Secretaries to Prime Sarah Priddy Ministers since 1906 This List notes Parliamentary Private Secretaries to successive Prime Ministers since 1906. Alex Burghart was appointed PPS to Boris Johnson in July 2019 and Trudy Harrison appointed PPS in January 2020. Parliamentary Private Secretaries (PPSs) are not members of the Government although they do have responsibilities and restrictions as defined by the Ministerial Code available on the Cabinet Office website. A list of PPSs to Cabinet Ministers as at June 2019 is published on the Government’s transparency webpages. It is usual for the Leader of the Opposition to have a PPS; Tan Dhesi was appointed as Jeremy Corbyn’s PPS in January 2020. Further information The Commons Library briefing on Parliamentary Private Secretaries provides a history of the development of the position of Parliamentary Private Secretary in general and looks at the role and functions of the post and the limitations placed upon its holders. The Institute for Government’s explainer: parliamentary private secretaries (Nov 2019) considers the numbers of PPSs over time. www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Parliamentary Private Secretaries to Prime Ministers since 1906 Prime Minister Parliamentary Private Secretary Notes Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (1905-08) Herbert Carr-Gomm 1906-08 Assistant Private Secretary Herbert Asquith (1908-16) 1908-09 Vice-Chamberlain of -

Thomas Kilroy

Thomas Kilroy A new version Gallery Books This new version of Characters Double Cross is published in October 2018 . william joyce, known as Lord Haw-Haw brendan bracken mp , Minister of Information The Gallery Press a fire warden Loughcrew popsie , an upper class English lady Oldcastle lord castlerosse, gossip columnist County Meath lord beaverbrook, proprietor of the Express newspapers Ireland margaret joyce, wife of William Joyce erich , an anglophile German and reader of W B Yeats www.gallerypress.com a lady journalist two narrators , one male, one female © Thomas Kilroy 2018 The play is so designed that two male and one female actors play isbn 978 1 91133 759 1 all the parts with one actor playing both brendan bracken and william joyce . A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. All rights whatsoever are strictly reserved. Requests to reproduce the text in whole or in part should be addressed to the publisher. Application for performance in any medium must be made in advance, prior to the commencement of rehearsals, and for translation into any language, to: Alan Brodie Representation Ltd, Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London ec1m 6ha . Double Cross receives financial assistance from the Arts Council. for Seamus Deane The Bracken Play: London Before the lights go up there is the sound of an air-raid siren in the distance and then the drone of bombers and distant explosions. The sounds are brought down. A darkened stage. Upstage: built into the set, so that they become integral parts of the set when they fade, two video/film screens. -

'The Fools Have Stumbled on Their Best Man by Accident': an Analysis of the 1957 and 1963 Conservative Party Leadership Selections

University of Huddersfield Repository Miller, Stephen David 'The fools have stumbled on their best man by accident' : an analysis of the 1957 and 1963 Conservative Party leadership selections Original Citation Miller, Stephen David (1999) 'The fools have stumbled on their best man by accident' : an analysis of the 1957 and 1963 Conservative Party leadership selections. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/5962/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ 'TBE FOOLS HAVE STLUvMLED ON TIHEIR BEST MAN BY ACCIDENT': AN ANALYSIS OF THE 1957 AND 1963 CONSERVATIVE PARTY LEADERSHIP SELECTIONS STEPBEN DAVID MILLER A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirementsfor the degreeof Doctor of Philosophy The Universityof Huddersfield June 1999 MHE FOOLS HAVE STUNIBLED ONT]HEIR BEST MAN BY ACCIDENT': AN ANALYSIS OF THE 1957AND 1963CONSERVATIVE PARTY LEADERSHIP SELECTIONS S.D. -

![Miranda, 2 | 2010, « Voicing Conflict : Women and 20Th Century Warfare » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Juillet 2010, Consulté Le 16 Février 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2961/miranda-2-2010-%C2%AB-voicing-conflict-women-and-20th-century-warfare-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-01-juillet-2010-consult%C3%A9-le-16-f%C3%A9vrier-2021-2512961.webp)

Miranda, 2 | 2010, « Voicing Conflict : Women and 20Th Century Warfare » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Juillet 2010, Consulté Le 16 Février 2021

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 2 | 2010 Voicing Conflict : Women and 20th Century Warfare Les voix du conflit : femmes et guerres au XXe siècle Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/322 DOI : 10.4000/miranda.322 ISSN : 2108-6559 Éditeur Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Référence électronique Miranda, 2 | 2010, « Voicing Conflict : Women and 20th Century Warfare » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 01 juillet 2010, consulté le 16 février 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/322 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.322 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 16 février 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. 1 SOMMAIRE Voicing Conflict : Women and 20th Century Warfare Introduction Karen Meschia Front Line Voices Voix sur la ligne de front X-Ray Vision: Women Photograph War Margaret R. Higonnet W.A.A.C.s: Crossing the line in the Great War Claire Bowen Roles in Conflict: The Woman War Reporter Maggie Allison Home Front Voices New Slants on Gender and Power Relations in British Second World War Films Elizabeth de Cacqueray “Careless Talk”: Word Shortage in Elizabeth Bowen’s Wartime Writing Céline Magot « A secret at the heart of darkness opening up » : de Little Eden-A Child at War (1978) à Journey to Nowhere (2008), les mots de la guerre ou les batailles du silence dans l'écriture autobiographique d'Eva Figes Nathalie Vincent-Arnaud Naomi the Poet and Nella the Housewife: Finding a Space to Write from The Wartime Diaries of Naomi Mitchison and Nella Last Karen Meschia Conflict, Power and Gender in Women’s Memories of the Second World War: a Mass- Observation Study Penny Summerfield Voices for Peace Woman as Peacemaker or the Ambivalent Politics of Myth Cyril Selzner Les Filles d’Athéna et des Amazones en Amérique Nicole Ollier Miranda, 2 | 2010 2 When Women Write the First Poem: Louise Driscoll and the “war poem scandal” Jennifer Kilgore-Caradec H.D. -

Anthology: Raw Materials for a History of The

Anthology raw materials for a history of the European Youth Forum Editorial Team Giuseppe Porcaro — Editor in Chief John Lisney — Editor Thomas Spragg — Assistant Editor * Anne Debrabandere — Translator Trupti Rami — Copy editor Antholog y James Higgins — Copy editor Alexis Jacob — Art director Feriz Sorlija — Curator * NOUN European Youth Forum Pronunciation : /anˈθɒlədʒi/ 120, rue Joseph II 1000, Bruxelles Origin : from the Greek word ἀνθολογία (anthologia ; Belgium – Belgique literally “flower-gathering”). In Greek, the word originally www.youthforum.org denoted a collection of the ‘flowers’ of verse, i.e. small choice poems or epigrams, by various authors. Collection of literary and artistic works chosen by the compiler. In partnership with It may be a collection of poems, short stories, plays, songs, or excerpts. HAEU with the support of / avec le soutien de : the European Commission la Commission européenne the European Youth Foundation of the Council of Europe Le Fonds européen pour la Jeunesse du Conseil de l’Europe 2011 European Youth Forum ISSN : 2032-9938 Disclaimer : The views and opinions expressed in this volume are those of the authors and artists and do not necessarily represent official positions of the European Youth Forum 6 Forewords 7 I am both honoured and humbled that as current President of the European Youth Forum (YFJ), I have the chance to write a foreword to this anthology Forewords on the occasion of the 15th anniversary of the merging of the three existing European youth platforms and the creation of the European Youth Forum. The reality in which the YFJ operates today is vastly different from the reality in which it came into being. -

Hatfield House Archives PAPERS of Elizabeth, 5 Marchioness Of

Hatfield House Archives PAPERS OF Elizabeth, 5th Marchioness of Salisbury - file list *Please note that the numbering of these papers is not final* Ref: 5MCH The collection comprises 12 boxes. Boxes 1-8 contain letters in bundles and each bundle has been treated as a file. Except bundle 1 (where the letters were numbered by Betty), letters in Box 1 and Box 2 bundle 1 have been numbered consecutively according to their original bundle e.g. letters in bundle 2 are numbered 2/1 – 57. These bundles were also divided into packets so that they could be foldered. This level of processing and repackaging could not be maintained in the time available for the project so from Box 2 bundle 2 onwards the original bundles have been retained with the total number of letters in each bundle being recorded. Letters are usually annotated with correspondent’s name and date of receipt by Betty, these names/nicknames have been used in the file lists to facilitate locating letters within the bundles. Full names and titles of significant correspondents are given in Appendix A. Unidentified correspondents are listed first for each bundle with additional information that may help to identify them later. Correspondents are listed once for each bundle containing their letter/letters. Box 1a, Box 1b Bundle 6, Box 3 Bundle 12-Box 8 Bundle 14 are listed alphabetically by surname but names have not been reversed Box 1b Bundle 7 & 8, Box 2 Bundle 1-Box 3 Bundle 11 are listed alphabetically by first name or title where no first name is given Box1b Bundles 9-11 and Box 2 Bundle2/1-20 only contain letters from “Bobbety”, Robert Gascoyne-Cecil Boxes 9 & 10 contain personal papers and ephemera which have been listed individually. -

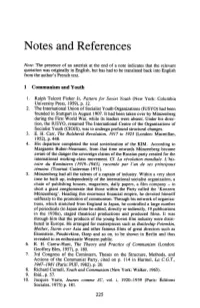

Notes and References

Notes and References Note: The presence of an asterisk at the end of a note indicates that the relevant quotation was originally in English, but has had to be translated back into English from the author's French text. 1 Communism and Youth I. Ralph Talcott Fisher Jr, Pattern for Soviet Youth (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959), p. 12. 2. The International Union of Socialist Youth Organizations (IUSYO) had been founded in Stuttgart in August 1907. It had been taken over by Miinzenberg during the First World War, while its leaders were absent. Under his direc tion, the IUS YO, renamed The International Centre of the Organizations of Socialist Youth (CIOJS), was to undergo profound structural changes. 3. E. H. Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, 1917 to 1923 (London: Macmillan, 1952), p. 448. 4. His departure completed the total sovietization of the KIM. According to Margarete Huber-Neumann, from that time onwards Miinzenberg became aware of the danger the sovereign claims of the Russian party created for the international working-class movement. Cf. La revolution mondiale. L'his toire du Komintern ( 1919-1943), racontee par l'un de ses principaux temoins (Tournai: Casterman 1971). 5. Miinzenberg had all the talents of a captain of industry. Within a very short time he built up, independently of the international socialist organization, a chain of publishing houses, magazines, daily papers, a film company - in short a giant conglomerate that those within the Party called the 'Konzern Miinzenberg'. Heading this enormous financial empire, he devoted himself selflessly to the promotion of communism. Through his network of organiza tions, which stretched from England to Japan, he controlled a large number of periodicals (in Japan alone he edited, directly or indirectly, 19 publications in the 1930s), staged theatrical productions and produced films. -

Evelyn Waugh Newsletter And

EVELYN WAUGH NEWSLETTER AND STUDIES Volume 26, Number 1 Spring, 1992 WAUGH'S LETTERS TO CYRIL CONNOLLY: THE TULSA ARCHIVE By Robert Murray Davis (University of Oklahoma) In 1975 the University of Tulsa acquired thirty-nine boxes of Cyril Connolly's papers. They are housed in the Special Collections division of McFarlin Library, and a "Guide to the Cyril Connolly Papers," prepared by Ms. Jennifer Carlson, is available from the library (600 South College Avenue, Tulsa, OK 74104-3189; phone (918) 631-2496; Bitnet: SHUTTNER@TULSA (for Sidney F. Huttner, Curator). Material by and to Waugh is contained in files 25 through 31 of Box 19. However, the materials have not been arranged in chronological order; some are undated; and not all of the dates assigned are accurate. The calendar which follows is designed first to inform students of Waugh about the existence of the collection and to indicate the importance of individual items and of the collection as a whole. Second, the calendar attempts to arrange the materials in chronological order. [1923?] Printed heading, Balliol College. Waugh wants to know what happened at [Basil?] Murray's tea; he refused to pay a subscription for a large gun. [Summer 1931]. To Jean Connolly, thanking her for having him to stay. Disliked Villefranche. Nina Seafeld was there; she had collected the major bores on the Riviera. Has come to Cabris, near Grasse, living with a crazy priest. Numbers, as scores, written in another hand. [Dating from letter to Henry Yorke, Summer 1931; Letters, p. 55.] [Early 1934] Sends regrets for cocktail party because he is in Fez writing a novel.