Evaluation of Alternative Ingredients As Fish Meal Replacers in On-Growing Diets for Red Porgy (Pagrus Pagrus)”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Husky Energy REPORT I

[ ~ Husky Energy REPORT I Labrador Shelf Seismic Program - Environmental Assessment Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board 5th Floor, TO Place 140 Water Street St. John's, NL A1C 6H6 Husky Energy 235 Water Street, Suite 901 St. John's, NL A1C 1B6 Signature: Date: February 26, 2010 Full Name and Francine Wight Title: Environment Lead Prepared by Reviewed by HDMS No.: 004085338 EC-HSE-SY-0003 1 All rights reserved. CONFIDENTlALIlY NOTE: No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the written permission of Husky Energy. EC-FT-00012 Labrador Shelf Seismic Program – Environmental Assessment Executive Summary Husky Energy proposes to undertake 2-D and 3-D seismic and follow-up geo-hazard surveys on its exploration acreage (Exploration Licenses 1106 and 1108) on the Labrador Shelf. Husky foresees the potential for a 2-D seismic survey in the summer of 2010, while other surveys – 2- D, 3-D or geo-hazard and Vertical Seismic Profiles – may occur at various times between 2010 and 2017. This document provides a Screening Level Environmental Assessment to allow the Canada- Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board (C-NLOPB) to fulfill its responsibilities under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act. During the course of the environmental assessment, Husky Energy consulted with stakeholders with an interest in the Project. Husky Energy and consultants undertook a consultation program with the interested stakeholders in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Nain, Rigolet, Postville, Hopedale, Cartwright, Makkovik and Sheshatshiu, as well as consultation with regulatory agencies and other stakeholders in St. -

BENTHOS Scottish Association for Marine Science October 2002 Authors

DTI Strategic Environmental Assessment 2002 SEA 7 area: BENTHOS Scottish Association for Marine Science October 2002 Authors: Peter Lamont, <[email protected]> Professor John D. Gage, <[email protected]> Scottish Association for Marine Science, Dunstaffnage Marine Laboratory, Oban, PA37 1QA http://www.sams.ac.uk 1 Definition of SEA 7 area The DTI SEA 7 area is defined in Contract No. SEA678_data-03, Section IV – Scope of Services (p31) as UTM projection Zone 30 using ED50 datum and Clarke 1866 projection. The SEA 7 area, indicated on the chart page 34 in Section IV Scope of Services, shows the SEA 7 area to include only the western part of UTM zone 30. This marine part of zone 30 includes the West Coast of Scotland from the latitude of the south tip of the Isle of Man to Cape Wrath. Most of the SEA 7 area indicated as the shaded area of the chart labelled ‘SEA 7’ lies to the west of the ‘Thunderer’ line of longitude (6°W) and includes parts of zones 27, 28 and 29. The industry- adopted convention for these zones west of the ‘Thunderer’ line is the ETRF89 datum. The authors assume that the area for which information is required is as indicated on the chart in Appendix 1 SEA678 areas, page 34, i.e. the west (marine part) of zone 30 and the shaded parts of zones 27, 28 and 29. The Irish Sea boundary between SEA 6 & 7 is taken as from Carlingford Lough to the Isle of Man, then clockwise around the Isle of Man, then north to the Scottish coast around Dumfries. -

Anomura and Brachyura

Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 1771 December 1990 A GUIDE TO DECAPOD CRUSTACEA FROM THE CANADIAN ATLANTIC: ANOMURA AND BRACHYURA Gerhard W. Pohle' Biological Sciences Branch Department of Fisheries and Oceans Biological Station St. Andrews, New Brunswick EOG 2XO Canada ,Atlantic Reference Centre, Huntsman Marine Science Centre St. Andrews, New Brunswick EOG 2XO Canada This is the two hundred and eleventh Technical Report from the Biological Station, St. Andrews, N. B. ii . © Minister of Supply and Services Canada 1990 Cat. No. Fs 97-611771 ISSN 0706-6457 Correct citation for this publication: Pohle, G. W. _1990. A guide to decapod Crustacea from the Canadian Atlantic: Anorrora and Brachyura. Can. Tech. Rep. Fish. Aquat. SCi. 1771: iv + 30 p. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract ..............................................................." iv Introduction 1 How to use this guide " 2 General morphological description 3 How to distinguish anomuran and brachyuran decapods 5 How to distinguish the families of anornuran crabs 6 Family Paguridae Pagurus acadianus Benedict, 1901 ........................................ .. 7 Pagurus arcuatus Squires, 1964 .......................................... .. 8 Pagurus longicarpus Say, 1817 9 Pagurus politus (Smith, 1882) 10 Pagurus pubescens (Kmyer, 1838) 11 Family Parapaguridae P.arapagurus pilosimanus Smith, 1879 12 Family Lithodidae Lithodes maja (Linnaeus, 1758) 13 Neolithodes grimaldii (Milne-Edwards and Bouvier, 1894) 14 Neolithodes agassizii (Smith 1882) 14 How to distinguish the families of brachyuran crabs 15 Family Majidae Chionoecetes opilio (Fabricius, 1780) 17 Hyas araneus (Linnaeus, 1758) 18 Hyas coarctatus Leach, 1815 18 Libinia emarginata Leach, 1815 19 Family Cancridae Cancer borealis Stimpson, 1859 20 Cancer irroratus Say, 1817 20 Family Geryonidae Chaceon quinquedens (Smith, 1879) 21 Family Portunidae Ovalipes ocellatus (Herbst,- 1799) 22 Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 ................................... -

Movement Ecology of the Greenland Shark

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 7-29-2020 Movement ecology of the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus): Identifying tools, management considerations, and horizontal movement behaviours using multi-year acoustic telemetry Jena Elizabeth Edwards University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Edwards, Jena Elizabeth, "Movement ecology of the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus): Identifying tools, management considerations, and horizontal movement behaviours using multi-year acoustic telemetry" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 8414. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/8414 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at -

13887-001.Pdf

FEDERATION FRANÇAISE DES SOCIETES DE SCIENCES NATURELLES B.P. 392 - 75232 PARIS Cedex 05 er J*^ ^ Association régie par la loi du 1 juillet 1901, fondée en 1919, reconnue d'utilité publique en 1S K 5L^< <»• Membre fondateur de l'UICN - Union Mondiale pour la Nature La FÉDÉRATION FRANÇAISE DES SOCIÉTÉS DE SCIENCES NATURELLES a été fondée en 1919 et reconnue d'utilité publique par décret du 30 Juin 1926. Elle groupe des Associations qui ont pour but, entièrement ou partiellement, l'étude et la diffusion des Sciences de la Nature. La FÉDÉRATION a pour mission de faire progresser ces sciences, d'aider à la protection de la Nature, de développer et de coordonner des activités des Associations fédérées et de permettre l'expansion scientifique française dans le domaine des Sciences Naturelles. (Art .1 des statuts). La FÉDÉRATION édite la « Faune de France ». Depuis 1921, date de publication du premier titre, 90 volumes sont parus. Cette prestigieuse collection est constituée par des ouvrages de faunistique spécialisés destinés à identifier des vertébrés, invertébrés et protozoaires, traités par ordre ou par famille que l'on rencontre en France ou dans une aire géographique plus vaste (ex. Europe de l'ouest). Ces ouvrages s'adressent tout autant aux professionnels qu'aux amateurs. Ils ont l'ambition d'être des ouvrages de référence, rassemblant, notamment pour les plus récents, l'essentiel des informations scientifiques disponibles au jour de leur parution. L'édition de la Faune de France est donc l'œuvre d'une association à but non lucratif animée par une équipe entièrement bénévole. -

Decapoda (Crustacea) of the Gulf of Mexico, with Comments on the Amphionidacea

•59 Decapoda (Crustacea) of the Gulf of Mexico, with Comments on the Amphionidacea Darryl L. Felder, Fernando Álvarez, Joseph W. Goy, and Rafael Lemaitre The decapod crustaceans are primarily marine in terms of abundance and diversity, although they include a variety of well- known freshwater and even some semiterrestrial forms. Some species move between marine and freshwater environments, and large populations thrive in oligohaline estuaries of the Gulf of Mexico (GMx). Yet the group also ranges in abundance onto continental shelves, slopes, and even the deepest basin floors in this and other ocean envi- ronments. Especially diverse are the decapod crustacean assemblages of tropical shallow waters, including those of seagrass beds, shell or rubble substrates, and hard sub- strates such as coral reefs. They may live burrowed within varied substrates, wander over the surfaces, or live in some Decapoda. After Faxon 1895. special association with diverse bottom features and host biota. Yet others specialize in exploiting the water column ment in the closely related order Euphausiacea, treated in a itself. Commonly known as the shrimps, hermit crabs, separate chapter of this volume, in which the overall body mole crabs, porcelain crabs, squat lobsters, mud shrimps, plan is otherwise also very shrimplike and all 8 pairs of lobsters, crayfish, and true crabs, this group encompasses thoracic legs are pretty much alike in general shape. It also a number of familiar large or commercially important differs from a peculiar arrangement in the monospecific species, though these are markedly outnumbered by small order Amphionidacea, in which an expanded, semimem- cryptic forms. branous carapace extends to totally enclose the compara- The name “deca- poda” (= 10 legs) originates from the tively small thoracic legs, but one of several features sepa- usually conspicuously differentiated posteriormost 5 pairs rating this group from decapods (Williamson 1973). -

5.5. Biodiversity and Biogeography of Decapods Crustaceans in the Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem the R

Biodiversity and biogeography of decapods crustaceans in the Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem Item Type Report Section Authors García-Isarch, Eva; Muñoz, Isabel Publisher IOC-UNESCO Download date 25/09/2021 02:39:01 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/9193 5.5. Biodiversity and biogeography of decapods crustaceans in the Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem For bibliographic purposes, this article should be cited as: García‐Isarch, E. and Muñoz, I. 2015. Biodiversity and biogeography of decapods crustaceans in the Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem. In: Oceanographic and biological features in the Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem. Valdés, L. and Déniz‐González, I. (eds). IOC‐ UNESCO, Paris. IOC Technical Series, No. 115, pp. 257‐271. URI: http://hdl.handle.net/1834/9193. The publication should be cited as follows: Valdés, L. and Déniz‐González, I. (eds). 2015. Oceanographic and biological features in the Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem. IOC‐UNESCO, Paris. IOC Technical Series, No. 115: 383 pp. URI: http://hdl.handle.net/1834/9135. The report Oceanographic and biological features in the Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem and its separate parts are available on‐line at: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/ioc/ts115. The bibliography of the entire publication is listed in alphabetical order on pages 351‐379. The bibliography cited in this particular article was extracted from the full bibliography and is listed in alphabetical order at the end of this offprint, in unnumbered pages. ABSTRACT Decapods constitute the dominant benthic group in the Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem (CCLME). An inventory of the decapod species in this area was made based on the information compiled from surveys and biological collections of the Instituto Español de Oceanografía. -

The Decapod Crustaceans of Madeira Island – an Annotated Checklist

©Zoologische Staatssammlung München/Verlag Friedrich Pfeil; download www.pfeil-verlag.de SPIXIANA 38 2 205-218 München, Dezember 2015 ISSN 0341-8391 The decapod crustaceans of Madeira Island – an annotated checklist (Crustacea, Decapoda) Ricardo Araújo & Peter Wirtz Araújo, R. & Wirtz, P. 2015. The decapod crustaceans of Madeira Island – an annotated checklist (Crustacea, Decapoda). Spixiana 38 (2): 205-218. We list 215 species of decapod crustaceans from the Madeira archipelago, 14 of them being new records, namely Hymenopenaeus chacei Crosnier & Forest, 1969, Stylodactylus serratus A. Milne-Edwards, 1881, Acanthephyra stylorostratis (Bate, 1888), Alpheus holthuisi Ribeiro, 1964, Alpheus talismani Coutière, 1898, Galathea squamifera Leach, 1814, Trachycaris restrictus (A. Milne Edwards, 1878), Processa parva Holthuis, 1951, Processa robusta Nouvel & Holthuis, 1957, Anapagurus chiroa- canthus (Lilljeborg, 1856), Anapagurus laevis (Bell 1845), Pagurus cuanensis Bell,1845, and Heterocrypta sp. Previous records of Atyaephyra desmaresti (Millet, 1831) and Pontonia domestica Gibbes, 1850 from Madeira are most likely mistaken. Ricardo Araújo, Museu de História Natural do Funchal, Rua da Mouraria 31, 9004-546 Funchal, Madeira, Portugal; e-mail: [email protected] Peter Wirtz, Centro de Ciências do Mar, Universidade do Algarve, Campus de Gambelas, 8005-139 Faro, Portugal; e-mail: [email protected] Introduction et al. (2012) analysed the depth distribution of 175 decapod species at Madeira and the Selvagens, from The first record of a decapod crustacean from Ma- the intertidal to abyssal depth. In the following, we deira Island was probably made by the English natu- summarize the state of knowledge in a checklist and ralist E. T. Bowdich (1825), who noted the presence note the presence of yet more species, previously not of the hermit crab Pagurus maculatus (a synonym of recorded from Madeira Island. -

ATLAS Deliverable 3.2

ATLAS Deliverable 3.2 Water masses controls on biodiversity and biogeography Project ATLAS acronym: Grant 678760 Agreement: Deliverable Deliverable 3.2 number: Work Package: WP3 Date of 28.02.2019 completion: Author: Lea‐Anne Henry (lead for D3.2), Patricia Puerta (alphabetical, all contributors are also authors) Sophie Arnaud‐Haond, Barbara Berx, Jordi Blasco, Marina Carreiro‐Silva, Laurence de Clippele, Carlos Domínguez‐Carrió, Alan Fox, Albert Fuster, José Manuel Gonzalez‐ Irusta, Konstantinos Georgoulas, Anthony Grehan, Cristina Gutiérrez‐ Zárate, Clare Johnson, Georgios Kazanidis, Francis Neat, Ellen Contributors Kenchington, Pablo Lozano, Guillem Mateu, Lenaick Menot, Christian Mohn, Telmo Morato, Ángela Mosquera, Francis Neat, Covadonga Orejas, Olga Reñones, Jesús Rivera, Murray Roberts, Alex Rogers, Steve Ross, José Luis Rueda, David Stirling, Karline Soetaert, Javier Urra, Johanne Vad, Dick van Oevelen, Pedro Vélez‐Belchí, Igor Yashayaev This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 678760 (ATLAS). This output reflects only the author's view and the European Union cannot be held responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. 1 Contents 1. Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Review: Influence of water masses on deep‐sea biodiversity and biogeography of the North Atlantic ........ 5 3. Case Studies -

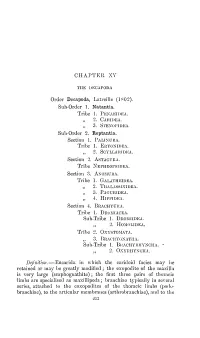

CHAPTER XV Order Decapoda, Latreille (1S02). Sub-Order 1

CHAPTER XV THE DECAPODA Order Decapoda, Latreille (1S02). Sub-Order 1. Natantia. Tribe 1. PEXAEIDEA. „ 2. CARIDEA. ,, 3. STEXOPIDEA. Sub-Order 2. Reptantia. Section 1. PALINURA. Tribe 1. ERYONIDEA. ,, 2. SCYLLARIDEA. Section 2. ASTACURA. Tribe XEPHROPSIDEA. Section 3. AXOMURA. Tribe 1. GALATHEIDEA. ,, 2. TlIALASSIXIDEA. ,, 3. PAGURIDEA. „ 4. HlPPIDEA. Section 4. BRACHYURA. Tribe 1. DROMIACEA. Sub-Tribe 1. DROMIIDEA. ,, 2. HOJIOLIDEA. Tribe 2. OXYSTOMATA. ,, 3. BRACIIYGXATIIA. Sub-Tribe 1. BRACHYRIIYNCIIA. - „ 2. OXYRHYXCIIA. Definition.—Eucarida in which the caridoid facies may lie retained or may be greatly modified; the exopodite of the maxilla is very large (scaphognathite); the first three pairs of thoracic limbs are specialised as maxillipeds; branchiae typically in several series, attached to the coxopoditcs of the thoracic limbs (podo- branchiae), to the articular membranes (arthrobranchiae), and to the •253 254 THE CRUSTACEA lateral walls of the thoracic somites (pleurobranchiae), very rarely absent; young rarely hatched in nauplius-stage. Historical.—The great majority of the larger and more familiar Crustacea belong to the Decapoda, and this Order received far more attention from the older naturalists than any of the others. A considerable number of species are mentioned by Aristotle, who describes various points of their anatomy and habits with accuracy, and sometimes with surprising detail. A long series of purely descriptive writers who have added to the number of known forms without contributing much to a scientific knowledge of them begins with Belon and Eondelet in the sixteenth century, and perhaps does not altogether come to an end with Herbst's Naturgeschichte der Krabben und Krebse (1782-180-i). Among the most noteworthy of early contributions to anatomy are Swammerdam's memoir on the Hermit-Crab (1737), and that of Eoesel von Rosenhof on the Crayfish (1755). -

Updating Changes in the Iberian Decapod Crustacean Fauna (Excluding Crabs) After 50 Years

SCIENTIA MARINA 82(4) December 2018, 207-229, Barcelona (Spain) ISSN-L: 0214-8358 https://doi.org/10.3989/scimar.04831.04A Updating changes in the Iberian decapod crustacean fauna (excluding crabs) after 50 years J. Enrique García Raso 1, Jose A. Cuesta 2, Pere Abelló 3, Enrique Macpherson 4 1 Universidad de Málaga, Departamento de Biología Animal, Campus de Teatinos s/n, 29071 Málaga, Spain. (JEGR) E-mail: [email protected]. ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3092-9518 2 Instituto de Ciencias Marinas de Andalucía, CSIC, Avda. República Saharaui 2, 11519 Puerto Real, Cádiz, Spain. (JAC) E-mail: [email protected]. ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9482-2336 3 Institut de Ciències del Mar, CSIC, Passeig Marítim de la Barceloneta 37-49, 08003 Barcelona, Spain. (PA) E-mail: [email protected]. ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6034-2465 4 Centre d’Estudis Avançats de Blanes, CSIC, Carrer d’Accés a la Cala Sant Francesc 14, 17300 Blanes, Spain. (EM) E-mail: [email protected]. ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4849-4532 Summary: An annotated checklist of the marine decapod crustaceans (excluding crabs) of the Iberian Peninsula has been compiled 50 years after the publication of “Crustáceos decápodos ibéricos” by Zariquiey Álvarez (1968). A total of 293 spe- cies belonging to 136 genera and 48 families has been recorded. This information increases by 116 species the total number reported by Zariquiey Álvarez in his posthumous work. The families with the greatest species richness are the Paguridae (28) and Palaemonidae (18). -

Hyperparasitism of the Cryptoniscid Isopod Liriopsis Pygmaea on the Lithodid Paralomis Granulosa from the Beagle Channel, Argentina

DISEASES OF AQUATIC ORGANISMS Vol. 58: 71–77, 2004 Published January 28 Dis Aquat Org Hyperparasitism of the cryptoniscid isopod Liriopsis pygmaea on the lithodid Paralomis granulosa from the Beagle Channel, Argentina Gustavo A. Lovrich1,*, Daniel Roccatagliata2, Laura Peresan2 1Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Centro Austral de Investigaciones Científicas (CADIC) CC 92, V9410BFD Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego, Argentina 2Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biología Experimental, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Ciudad Universitaria, C1428EHA Buenos Aires, Argentina ABSTRACT: A total of 29 570 false king crab Paralomis granulosa were sampled from the Beagle Channel (54° 51’ S, 68° 12’ W), Tierra del Fuego, Argentina, between July 1996 and August 1998. Crab size varied from 6.8 to 111.2 mm carapace length (CL). A few crabs parasitized by the rhizo- cephalan Briarosaccus callosus were found; prevalences of externae (the rhizocephalan reproductive body) and scars (the mark left on the host after the death of the parasite) were 0.28 and 0.16%, re- spectively. Of 85 externae examined, 55 were non-ovigerous and 30 ovigerous. The cryptoniscid iso- pod Liriopsis pygmaea infested 36.5% of the B. callosus examined. The most abundant stage was the cryptonicus larva, accounting for 208 of the 238 L. pygmaea recovered. Cryptonisci showed a highly aggregated distribution. A total of 92.7% of cryptonicsci were recovered inside empty externae, sug- gesting that the latter were attractive to cryptonisci. Early subadult females of L. pygmaea were rare; only 3 individuals occurred inside 1 ovigerous externa. Eight late subadult and 18 adult females were found on 3 and 7 non-ovigerous externae, respectively; in addition, 1 aberrant late subadult was found on 1 ovigerous externa.