Postmedlincs.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Humber Metro

The Humber Metro The Humber Metro is a very futuristic concept, depending, as it does, on the existence of the Humber tunnel between Goxhill and the approach to Paragon station, proposed as part of HS10 in the ‘HS Eastern Routes and Service Plans’ article. As noted there, although the tunnel will be built to GC gauge, it is intended from the outset to be shared with Regional Metro traffic between Cleethorpes and Hull, which will at least initially be of UK loading gauge. The Humber Metro covers the area from Selby and Goole in the west to Cleethorpes and Withernsea in the east, and from Grimsby in the south to Bridlington in the north. The core section, built to GC-gauge, as all new infrastructure should be, runs in tunnel under the centre of Hull between Paragon (LL) and Cannon St. (former H&B) stations, with a connection to the Hornsea / Withernsea lines just before Wilmington, and another to the Beverley line at Cottingham. Other than that (and the Humber tunnel, of course,) it takes over the routes of existing and former, long closed, branches. The proposed metro services fall into two groups, either cross-river or west-east along the north bank. The services of the first group are: 2tph Cleethorpes – New Clee – Grimsby Docks – Grimsby Town – West Marsh – Great Coates – Healing – Stallingborough – Habrough – Ulceby – Thornton Abbey – Goxhill – Hull Paragon (LL) – George St. – Cannon St. – Beverley Rd. – Jack Kaye Walk – Cottingham – Beverley – Arram – Lockington – Hutton Cranswick – Great Driffield – Nafferton – Lowthorpe – Burton Agnes – Carnaby – Bridlington 2tph Cleethorpes – New Clee – Grimsby Docks – Grimsby Town – West Marsh – Great Coates – Healing – Stallingborough – Habrough – Ulceby – Thornton Abbey – Goxhill – Hull Paragon (LL) – George St. -

Display PDF in Separate

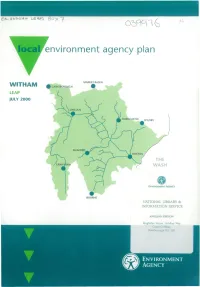

^ / v^/ va/g-uaa/ Ze*PS o b ° P \ n & f+ local environment agency plan WITHAM LEAP JULY 2000 NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE ANGLIAN REGION Kingfisher House, Goldhay Way, Orton Goldhay, ▼ Peterborough PE2 SZR T En v ir o n m e n t Ag e n c y T KEY FACTS AND STATISTICS Total Area: 3,224 km2 Population: 347673 Environment Agency Offices: Anglian Region (Northern Area) Lincolnshire Sub-Office Waterside House, Lincoln Manby Tel: (01522) 513100 Tel: (01507) 328102 County Councils: Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire District Councils: West Lindsey, East Lindsey, North Kesteven, South Kesteven, South Holland, Newark & Sherwood Borough Councils: Boston, Melton Unitary Authorities: Rutland Water Utility Companies: Anglian Water Services Ltd, Severn Trent Water Ltd Internal Drainage Boards: Upper Witham, Witham First, Witham Third, Witham Fourth, Black Sluice, Skegness Navigation Authorities: British Waterways (R.Witham) 65.4 km Port of Boston (Witham Haven) 10.6 km Length of Statutory Main River: 633 km Length of Tidal Defences: 22 km Length of Sea Defences: 20 km Length of Coarse Fishery: 374 km Length of Trout Fishery: 34 km Water Quality: Bioloqical Quality Grades 1999 Chemical Qualitv Grades 1999 Grade Length of River (km) Grade Length of River (km) "Very Good" 118.5 "Very Good" 11 "Good" 165.9 "Good" 111.6 "Fairly Good" 106.2 "Fairly Good" 142.8 "Fair" 8.4 "Fair" 83.2 "Poor" 0 "Poor" 50.4 "Bad" 0 "Bad" 0 Major Sewage Treatment Works: Lincoln, North Hykeham, Marston, Anwick, Boston, Sleaford Integrated Pollution Control Authorisation Sites: 14 Sites of Special Scientific Interest: 39 Sites of Nature Conservation Interest: 154 Nature Reserves: 12 Archaeological Sites: 199 Licensed Waste Management Facilities: La n d fill: 30 Metal Recycling Facilities: 16 Storage and Transfer Facilities: 35 Pet Crematoriums: 2 Boreholes: 1 Mobile Plants: 1 Water Resources: Mean Annual Rainfall: 596.7 mm Total Cross Licensed Abstraction: 111,507 ml/yr % Licensed from Groundwater = 32 % % Licensed from Surface Water = 68 % Total Gross Licensed Abstraction: Total no. -

Walk 9 - a Walk to the Past

Woodhall Spa Walks No 9 Walk 9 - A walk to the past Start from Royal Square - Grid Reference: TF 193631 Approx 1 hour This route takes the walker to the ruins of Kirkstead Abbey, (dissolved by Henry VIII over 300 years before Woodhall Spa came into being) and the little 13th Century Church of St Leonards. From Royal Square, take the Witham Road, towards the river, passing shops and houses until fields open out to your left. Soon after, look for the entrance to Abbey Lane (to the left). Follow this narrow lane. You will eventually cross the Beck (see also walks 6 and 7) as it approaches the river; the monks from the Abbey once re-routed it to obtain drinking water. Ahead, on the right, is Kirkstead Old Hall, which dates from the 17th Century. Following the land, you cannot miss the Abbey ruin ahead. All that remains now is part of the Abbey Church, but under the humps and bumps of the field are other remains that have yet to be properly excavated, though a brief exploration before the laqst war revealed some of the magnificence of the Cistercian Abbey. Beyond is the superb little Church of St Leonards ( the patron saint of prisoners), believed to have been built as a Chantry Chapel and used by travellers and local inhabitants. The Cistercians were great agriculturalists and wool from the Abbey lands commanded a high price for its quality. A whole community of craftsmen and labourers would have grown up around the Abbey as iut gained lands and power. -

![LINCOLN.] Farmers-Continued](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2008/lincoln-farmers-continued-172008.webp)

LINCOLN.] Farmers-Continued

TltADES DIRlW'l;ORY.] 415 FAR [LINCOLN.] FARMERs-continued. Cottingham Edmund, Snarford, Market Coy D. Central Wingland, Wisbech Cook John Hall, Salmonby, Horncastle Rasen Coy J. Donington Spalding Cook Joseph, Owston ferry, Bawtry Cottingham Edwin, Snarford, Market Coy J. Epworth, Bawtry CookJosephWilliam,Kirton-in-Linusey Rasen Coy T. Fen, Gosberton, Spalding Cook Mrs. M. Nettleton, Caistor Cottingham Mrs. Elizabeth, West Craft J. Fen, Algarkirk, Spalding Cook R. Holton-le-Moor, Caistor Barkwith, Wragby Cragg D. Westborough, Grantham Cook T. West Ashby, Horncastle Cottingham H. Linwood, Blankney, Cragg J. Tydd St. Mary, Wisbech Cook W. Gayton-le-.Marsh, Alford Sleaford Cragg W. Sutton St. James, Wisbech Cook W. Hemingby, Horncastle Cottingham J.Scotter,Kirton-in-Lindsy Cram T. Burgh-in-the-Marsh, Boston Cook W. Tattershall, Boston Cottingham Mrs. M. Friesthorpe, Cramp ton J. Cow bit, Spalding Cook W. G. S. Upton, Gainsborough Market Rasen Crane Mrs. E. Moulton, Spalding Cooke B. Station rd. Postland,Crowland Cottrill B. N orthOwersby, MarketRasen Crane J. Ealand, Crow le, Bawtry Cooke E. Friskney Boston Coulam G. Withem, Alford Crane J. Quadring, Spalding Cooke H. Postland, Crowland Coulbeck W. & H. Cleethorpes, Great Crane W. Fleet, Wisbech Cooke James, Pode hole, Spalding Grimsby Cranidge E. Crowle, Bawtry Cooke John, North Thorsby, Louth Coulbeck R. Ashby, Brigg Cranidge John, Crowle, Bawtry Cooke John, Wainfleet, Boston CoulbeckR.Barrow-on-Humber,Ulceby Cranidge Jonathan, Crowle, Bawtry Cooke John, Wyberton, Boston Coulbeck W. Apple by, Brigg Cranidge J osepb Margrave,. Crowle, CookeR. Navenby, Grantham Coulbeck W. Broughton, Brigg Bawtry Cooke Robert D. Everard house, Post- Coulman E. Belton, Bawtry Cranidge P. -

Lincolnshire.. Far 683

TRADES DIRECTORY.] LINCOLNSHIRE.. FAR 683 Darnell William, Bardney, Lincoln Dawson William, Nettleton, Caistor Dickinson Thomas, Friskney, Boston Darnill George, Orby, Boston Dawson Wm. Skeldyke, Kirton, Boston DickinsonW.Sandpits,Westhorpe,Spaldg Darnill Jn. Jack, Grainthorpe, Grimsby Dawson William, Union road, Caistor Dickinson Wm. Westhorpe, Spalding Daubeny Jabez, North Kyme, Lincoln Day Edward Jas. Messingham, Brigg Dickson Frederick, Tumby, Boston Dauber John William, Ruckland, Louth Day John, Wood Enderby, Boston Diggle E. Suttun St. Edmunds, Wisbech Daubney C. Hagworthingham, Spilsby Day John Wm. Scatter, Kirton Lindsey Diggle J.H. Loosegate rd. Moultn.Spldng Dau bney Charles, Leake, Boston Day Ro bt. Scotter Hig hfield, Ki rtonLindsy DiggleJ ohnHarber, j u n. Moulton, Spaldng Daubney Charles, jun. Leake, Boston Day Robert,Scotterthorpe,KirtonLindsy Diggle Thos. Ewerby Thorpe, Sleaford Daubney George, Belchford, Horncastle Day Thomas, Church street, Caistor Diggle Thomas, Weston, Spalding Daubney H.Manor frm.Canwick, Lincoln Day William, Scatter, Kirton Lindsey Dilworth James, Horse Shoe rd.Spaldmg Daubney Henry, Wyberton, Boston Day Wm. Cotehouses, 0 wston Ferry Dimbleby W .BishopNortn. Kirtn.Lindsy Daubney James, Navenby S.O Dean Arthur W. Dowsby, Falkingham Dinnis Thomas, Anderby, Alford Daulton Austin, West Keal, Spilsby Dean Edward, Algarkirk, Boston Dinnison Thomas Hy. Burr la. Spalding Daulton Henry, Bilsby, Alford Dean John, Drayton, Swineshead,Boston Dinsdale John, Nth.Killingholme, Ulceby Daulton Jesse, The Grange, East Keal Dean John, Drove end, Wisbech Dion Frederick, Sibsey, Boston Coates, East Keal, Spilsby Dean John, Goxhill, Hull Dion James, Sibsey, Boston Daulton Joseph, Keal Coates, Spilsby Dean John Chas. Drove end, Wisbech Dion Jesse, Sibsey, Boston Daulton Thomas, East Kirkby, Spilsby Dean John Hy. -

LINCOLNSHIRE. [ Kl:'LLY's

- 780 FAR LINCOLNSHIRE. [ Kl:'LLY's F ARMER~-continued. Anderson Charles, Epworth, Doncaster Atldn Geo. Common, Crowland, Peterboro' Abraham Everatt, Barnetby-le-Wold R.S.O Anderson G. High st. Long Sutton, Wisbech Atltin Geo. Hy. West Pinchbeck, Spalding Abrabam Henry, Aunsby, Sleaford Anderson John, High st. Barton-on-Humber Atkin John, Mareham-le-Fen, Boston Abrnham Jn. Otby ho. Walesby,:Market Ra.sen Anderson John, Epworth, Doncaster Atkin John, Skidbrook, Great Grimsby Ahraham S. Toft ho. Wainfieet St.Mary R.S.O AndersonJn. j un. Chapel farm, Brtn. -on-Hm br A tkin J n. Wm. The Gipples, Syston, G rantham Abraha.m William, Croxby, Caistor AndersonR. Waddinghm.KirtonLindseyR.S.O Atkin Joseph, Bennington, Boston Abrahams Wm. Park, Westwood side,Bawtry Anderson Samuel, Anderby, Alford Atkin Richard, Withern, Alford Aby Edward, Thornton Curtis, Ulceby Andrew Charles, North Fen, Bourn Atkin Tom, Cowbit, Spalding Aby Mrs. Mary & Joseph, Cadney, Brigg Andrew Edwd. Grubb hi. Fiskerton, Lincoln Atkin Tom, Moulton, Spalding Achurch Hy.Engine bank, Moulton, Spalding Andrew James Cunnington, Fleet, Holbeach Atkin William, Fosdyke, Spalding Achurc;h J.DeepingSt.James,Market Deeping Andrew John, Deeping St. Nicholas, Pode AtkinWm.Glebe frrn. Waddington hth.Lincln Acrill William, Fillingham, Lincoln Hole, Spalding Atkin William, Swineshead, Spalding Adams Mrs. Ann, Craise Lound, Bawtry Andrew John, Gunby, Grantham Atkin William, Whaplode, Spalding Adarns George, Epworth, Doncaster Andrew John, 5 Henrietta. street, Spalding Atkins George, Mill lane, South Somercotes, Adarns Isaac Crowther, Stow park, Lincoln Andrew John, Hunberstone, Great Grimsby Great Grimsby Adams John, Collow grange, Wragby Andrew John, Somerby, Grantham Atkinson Jsph. & Jas. Pointon, Falkingham Adams Luther, Thorpe-le-Yale, Ludford, Andrew J oseph, Butterwick, Boston Atkinson Abraharn,Sea end,Moulton,Spaldng Market Rasen Andrew Willey,South Somercotes,Gt.Grmsby Atkinson Abraham, Skellingthorpe, Lincoln Adcock Charles, Corby, Grantham Andrcw Wm. -

Closure of Toftstead Primary School, Amber Hill

Report Reference: 1.0 Executive/Executive Councillor Open Report on behalf of Peter Duxbury, Executive Director - Children's Group Mrs P A Bradwell, Executive Councillor for Children's Report to: Services including Post 16 Education Date: 17 June 2010 Proposal to discontinue Toftstead Primary School, Subject: Amber Hill Decision Reference: 01741 Key decision? Yes Summary: This report seeks to advise the Executive Councillor on making a decision regarding the proposed closure of Toftstead Primary School, Amber Hill. This proposal is being made in the context of very low current and projected pupil numbers in the area leading to an irreversible deficit budget as well as serious concern over the quality of education the school is able to offer its pupils. Falling rolls have meant that the school has been unable to sustain the number of pupils necessary to generate a budget sufficient to maintain the standard of education all children deserve. The school, supported by the Local Authority school improvement partner (CfBT), have explored options to maintain the viability of the school including federation. The Governing Body requested that the Local Authority (LA), the decision maker, co-ordinate consultation on the future of Toftstead Primary School and subsequently the LA has consulted on the proposal to close the school in accordance with the Education and Inspections Act 2006 (EIA 2006) and the guidance of the Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF), now the Department for Education (DfE). This proposal would address the issues surrounding a primary school population in decline in recent years with no sign of recovery, in an area where there are other appropriate schools in more densely populated areas which have sufficient capacity to accommodate displaced pupils. -

Lincolnshire

Archaeological Investigations Project 2003 Field Evaluations East Midlands LINCOLNSHIRE Boston 2/55 (C.32.O043) TF 33974383 PE21 0EE FORBES ROAD CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH Forbes Road Congregational Church, Boston, Lincolnshire Rylatt, J Lincoln : Pre-Construct Archaeology Ltd., 2003, 22pp, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Pre-Construct Archaeology Ltd. Trial trenches were excavated at the site. No features were encountered but medieval and post- medieval finds were recovered. [Au(abr)] Archaeological periods represented: MD, PM 2/56 (C.32.O048) TF 32764341 PE21 8TJ LAND AT 138-142 HIGH STREET, BOSTON Archaeological Evaluation on Land at 138-142 High Street, Boston, Lincolnshire Snee, J Sleaford : Archaeological Project Services, 2003, 54pp, colour pls, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Archaeological Project Services Trial trenches were excavated on the site. River bank deposits dating from the medieval period to the 17th century were identified. The land was reclaimed in the 18th century and dumping deposits were identified for this period. Cellars and building structures were identified dating to the 19th century. [Au(abr)] Archaeological periods represented: PM 2/57 (C.32.O003) TF 40905009 PE22 9LE LAND AT HADWICK MOTORS, CHURCH ROAD, OLD LEAKE Land at Hardwick Motors, Church Road, Old Leake, Lincolnshire Hall, R Sleaford : Archaeological Project Services, 2003, 26pp, colour pls, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Pre-Construct Archaeology Ltd. Evaluation trenches were excavated on the site. Two undated ditches, an infilled dyke and a post- medieval pit were identified. [Au(abr)] Archaeological periods represented: PM, UD 2/58 (C.32.O040) TF 42395087 PE22 9AQ LAND AT THE ANGEL INN Land at The Angel Inn, Church End, Wrangle, Lincolnshire Bradley-Lovekin, T Sleaford : Archaeological Project Services, 2003, 32pp, colour pls, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Archaeological Project Services Two trial trenches were excavated at the site. -

217 Bibliography Primary Historical Sources 'Order Of

217 Bibliography Primary Historical Sources ‘Order of the Commissioners of Sewers for the Avon.’ Wiltshire and Swindon Record Office, PR/Salisbury St Martin/1899/223 - date 1592. ‘Regulation of the River Avon.’ Hampshire Record Office. 24M82/PZ3. 1590-91. ‘Return of the Ports, Creeks and Landing places in England. 1575.’ The National Archives. SP12/135 dated 1575. ‘Will, Inventory of John Moody (Mowdy) of Kings Somborne, Hampshire. Tailor.’ Hampshire Record Office. 1697A/099. 1697. ‘Will, Inventory of Joseph Warne of Bisterne, Ringwood, Hampshire, Yeoman.’ Hampshire Record Office 1632AD/87. ‘Order of the Commissioners of Sewers.’ Wiltshire and Swindon Record Office, PR/Salisbury St Martin/1899/223. 1592. Printed official records from before 1600 Acts of the Privy Council. 1591-92. Calendar of Close Rolls. 1227-1509, 62 volumes. Calendar of Fine Rolls. 1399-1509, 11 volumes. Calendar of Inquisitions Miscellaneous. 1216-1509, 21 volumes. Calendar of Liberate Rolls. 1226-1272, 6 volumes. Calendar of Memoranda Rolls. (Exchequer.) 1326-1327. Calendar of Patent Rolls. 1226-1509, 59 volumes. Calendar of Patent Rolls. 1547-1583, 19 volumes. Curia Regis Rolls. Volume 16. 21-26 Henry 3. Letters and Papers Foreign and Domestic of the Reign of Henry VIII. 1519-1547, 36 volumes. Liber Assisarum et Placitorum Corone. 23 Edward I. The Parliamentary Rolls of Medieval England. 1272 – 1504. (CD Version 2005.) 218 Placitorum in Domo Capitulari Westmonasteriensi Asservatorum Abbreviatio. (Abbreviatio Placitorum.) 1811. Rotuli Hundredorum. Volume I. Statutes at Large. 42 Volumes. Statutes of the Realm. 12 Volumes. Year Books of the Reign of King Edward the Third. Rolls Series. Year XIV. Printed offical records from after 1600 Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, of the Reign of Charles I. -

North Lincolnshire

Archaeological Investigations Project 2003 Post-Determination & Non-Planning Related Projects Yorkshire & Humberside NORTH LINCOLNSHIRE North Lincolnshire 3/1661 (E.68.M002) SE 78700380 DN9 1JJ 46 LOCKWOOD BANK Time Team Big Dig Site Report Bid Dig Site 1845909. 46 Lockwood Bank, Epworth, Doncaster, DN9 1JJ Wilkinson, J Doncaster : Julie Wilkinson, 2003, 13pp, colour pls, figs Work undertaken by: Julie Wilkonson A test pit produced post-medieval pottery and clay pipe stems and a sherd of Anglo-Saxon pottery. [AIP] SMR primary record number:SLS 2725 Archaeological periods represented: EM, PM 3/1662 (E.68.M012) SE 92732234 DN15 9NS 66 WEST END, WINTERINGHAM Report on an Archaeological Watching Brieff Carried out at Plot 3, 66 West End, Winteringham, North Lincolnshire Atkins, C Scunthorpe : Caroline Atkins, 2003, 8pp, figs Work undertaken by: Caroline Atkins Very few finds were made during the period of archaeological supervision, other than fragments of assorted modern building materials, and only one item, a sherd from a bread puncheon, might have suggested activity on the investigated part of the site prior to the twentieth century. [Au(abr)] SMR primary record number:LS 2413 Archaeological periods represented: MO, PM 3/1663 (E.68.M008) SE 88921082 DN15 7AE CHURCH LANE, SCUNTHORPE An Archaeological Watching Brief at Church Lane, Scunthorpe Adamson, N & Atkinson, D Kingston upon Hull : Humber Field Archaeology, 2003, 6pp, colour pls, figs, refs Work undertaken by: Humber Field Archaeology Monitoring of the site strip and excavation of the foundation trench systems revealed the location of a former garden pond. No archaeological features and no residual archaeological material was identified within the upper ground layers. -

Our Resource Is the Gospel, and Our Aim Is Simple;

Bolingbroke Deanery GGr raappeeVViinnee MAY 2016 ISSUE 479 • Mission Statement The Diocese of Lincoln is called by God to faithful worship, confident discipleship and joyful service. • Vision Statement To be a healthy, vibrant and sustainable church, transforming lives in Greater Lincolnshire 50p 1 Bishop’s Letter Dear Friends, Many of us will have experienced moments of awful isolation in our lives, or of panic, or of sheer joy. The range of situations, and of emotions, to which we can be exposed is huge. These things help to form the richness of human living. But in themselves they can sometimes be immensely difficult to handle. Jesus’ promise was to be with his friends. Although they experienced the crushing sadness of his death, and the huge sense of betrayal that most of them felt in terms of their own abandonment of him, they also experienced the joy of his resurrection and the happiness of new times spent with him. They would naturally have understood that his promise to ‘be with them’ meant that he would not physically leave them. However, what Jesus meant when he said that they would not be left on their own was that the Holy Spirit would always be with them. It is the Spirit, the third Person of the Holy Trinity, that we celebrate during the month of May. Jesus is taken from us, body and all, but the Holy Spirit is poured out for us and on to us. The Feast of the Holy Spirit is Pentecost. It happens at the end of Eastertide, and thus marks the very last transition that began weeks before when, on Ash Wednesday, we entered the wilderness in preparation for Holy Week and Eastertide to come. -

LINCOLNSHIRE. F .Abmers-Continmd

F..AR. LINCOLNSHIRE. F .ABMERs-continmd. Mars hall John Jas.Gedney Hill, Wisbech Mastin Charles, Sutterton Fen, Boston Maplethorpe Jackson, jun. Car dyke, Marshal! John Thos. Tydd Gate, Wibbech 1Mastin Fredk. jun. Sutterton Fen, Boston Billinghay, Lincoln Marsball John Thos. Withern, Alford Mastin F. G. Kirkby Laythorpe, Sleafrd Maplethorpe Jn. Bleasby, Lrgsley, Lncln Marshall Joseph, .Aigarkirk, Boston Mastin John, Tumby, Boston Maplethorpe Jsph. Harts Grounds,Lncln Marbhall Joseph, Eagle, Lincoln Mastin William sen. Walcot Dales, Maplethorpe Wm. Harts Grounds,Lncln MarshalJJsph. The Slates,Raithby,Louth Tattershall Bridge, Linco·n Mapletoft J. Hough-on-the-Hill, Grnthm Marshall Mark,Drain side,Kirton,Boston Mastin Wm. C. Fen, Gedney, Ho"beach Mapletoft Robert, Nmmanton, Grar.thm Marshall Richard, Saxilby, Lincoln Mastin Wi!liam Cuthbert, jun. Walcot Mapletoft Wil'iam, Heckington S.O Marshall Robert, Fen, :Fleet, Holbeach Dales, Tattel"!lhall Bridge, Lincoln Mappin S. W.Manor ho. Scamp ton, Lncln Marshall Robert, Kral Coates, Spilsby Matthews James, Hallgate, Sutton St. Mapplethorpe William, Habrough S.O Marshall R. Kirkby Underwood, Bourne Edmunds, Wisbech Mapplethorpe William Newmarsh, Net- Marshal! Robert, Northorpe, Lincoln Maultby George, Rotbwell, Caistor tleton, Caistor Marshall Samuel, Hackthorn, Lincoln Maultby James, South Kelsey, Caistor March Thomas, Swinstead, Eourne Marshall Solomon, Stewton, Louth Maw Allan, Westgate, Doncaster Marfleet Mrs. Ann, Somerton castle, Marshall Mrs. S. Benington, Boston Maw Benj. Thomas, Welbourn, Lincoln Booth by, Lincoln Marshall 'fhomas, Fen,'fhorpe St.Peter, Maw Edmund Hy. Epworth, Doncaster Marfleet Charles, Boothby, Lincoln Wainfleet R.S.O Maw George, Messingham, Brigg Marfleet Edwd. Hy. Bassingbam, Lincln Marshall T. (exors. of), Ludboro', Louth Maw George, Wroot, Bawtry Marfleet Mrs.