Free Fulltext

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ICC-ASP/11/18 Assembly of States Parties

International Criminal Court ICC-ASP/11/18 Distr.: General Assembly of States Parties 9 November 2012 Original: English Eleventh session The Hague, 14-22 November 2012 Designation of the members of the Advisory Committee on Nominations Note by the Secretariat By resolution ICC-ASP/9/Res.5,1 the Assembly welcomed the report2 adopted by the Bureau pursuant to paragraph 25 of resolution ICC-ASP/9/Res.3 and adopted the recommendations contained therein. It also requested the Bureau to start the process of preparing the election, by the Assembly of States Parties, of the members of the Advisory Committee on nominations of judges of the International Criminal Court in accordance with the terms of reference of the Advisory Committee. Article 36, paragraph 4 (c), of the Rome Statute provides as follows: “(c) The Assembly of States Parties may decide to establish, if appropriate, an Advisory Committee on nominations. In that event, the Committee’s composition and mandate shall be established by the Assembly of States Parties.” The terms of reference of the Advisory Committee on Nominations provide that: “The Committee should be composed of nine members, nationals of States Parties, designated by the Assembly of States Parties by consensus on recommendation made by the Bureau of the Assembly also made by consensus, reflecting the principal legal systems of the world and an equitable geographical representation, as well as a fair representation of both genders, based on the number of States Parties to the Rome Statute.”3 At its 11th meeting, on 1 May 2012, the Bureau fixed the nomination period to run for 12 weeks, from 16 May to 8 August 2012 (Central European Time). -

The International Criminal Court Prosecutor Seeks a Warrant Written by Benjamin Schiff

The Politics of Justice: The International Criminal Court Prosecutor seeks a Warrant Written by Benjamin Schiff This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. The Politics of Justice: The International Criminal Court Prosecutor seeks a Warrant https://www.e-ir.info/2008/07/16/the-politics-of-justice-the-international-criminal-court-prosecutor-seeks-a-warrant/ BENJAMIN SCHIFF, JUL 16 2008 There is some irony in the criticism of ICC Chief Prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo for issuing his request for a warrant of arrest for Sudanese President Omar Hassan Ahmad Al Bashir. Approximately two years ago, responding to the request of the Pre-Trial Chamber (PTC I), amicus filings from two distinguished commentators – Judge Antonio Cassese (who had chaired the International Commission of Inquiry into the Sudan1 that reported to the Secretary-General and UN Security Council (UNSC) in early 2005, leading to the UNSC’s March 31 referral of the situation to the ICC), and Judge Louise Arbour (former Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and by 2005 the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights) – indicated that the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) should move more quickly and against high levels of the Sudanese government in order to pressurize it to protect the citizens of Darfur and to be more visibly pursuing justice in the situation.2 Within the wider non-governmental organization (NGO) human rights community, the OTP was criticized for moving too slowly and cautiously. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Ambos, Kai. “Article 25. Individual Criminal Responsibility.” In Commentary on the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, edited by Otto Triffterer. Baden- Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, 1999. Ambos, Kai. “Defences.” In General Principles of International Criminal Law, edited by Antonio Cassese, Paola Gaeta and John R.W.D. Jones. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. Ambos, Kai. “What does intent to destroy mean?” International Review of the Red Cross 91 (2009): 833–858. Ambos, Kai, “Grounds Excluding Responsibility (‘Defences’).” In Treatise on Interna- tional Criminal Law: Volume 1: Foundations and General Part, edited by Kai Ambos. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. Ambos, Kai. Treatise on International Criminal Law: Volume I: Foundations and General Part. Oxford Scholarly Authorities on International Law, 2013. Ambos, Kai. Treatise on International Criminal Law: Volume II: The Crimes and Sentenc- ing. Oxford Scholarly Authorities on International Law, 2014. Anggadi, Frances, Greg French and James Potter. “Negotiating the Elements of the Crime of Aggression.” In Crime of Aggression Library: The Travaux Préparatoires of the Crime of Aggression, edited by Stefan Barriga and Claus Kreß. Cambridge: Cam- bridge University Press, 2012. Astill, James. “Strike one.” The Guardian. 2 October 2001. Accessed 20 June 2016. http:// www.theguardian.com/world/2001/oct/02/afghanistan.terrorism3. Badar, Mohamed Elewa. “Drawing the Boundaries of Mens rea in the Jurisprudence of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia.” International Crimi- nal Law Review 6 (2006). Badar, Mohamed Elewa. “The Mental Element in the Rome Statute of the Internation- al Criminal Court: A Commentary from a Comparative Law Perspective.” Criminal Law Forum 19 (2008). -

Conspiracy to Commit Genocide and Its Exclusion from the ICC Statute by SONG Tianying FICHL Policy Brief Series No

POLICY BRIEF SERIES Conspiracy to Commit Genocide and its Exclusion From the ICC Statute By SONG Tianying FICHL Policy Brief Series No. 18 (2014) 1. Introduction fact that in practice genocide is a collective crime, presup- The criminal classification ‘conspiracy’ may denote either posing the collaboration of a greater or smaller number of 6 a substantive crime or a mode of liability. As a substantive persons”. During the subsequent discussion over the crime, it punishes the agreement of two or more persons draft, a number of states that did not have the concept of to commit a crime, irrespective of whether the intended conspiracy in their domestic law pointed out that the pro- crime is committed or not.1 It is generally recognized as a vision needed to be applied according to principles of 7 crime specific to the common law tradition. Conspiracy each penal system. as a form of liability attributes responsibility to co-con- The Statute of the International Criminal Court (‘ICC’) spirators where the intended crime is committed.2 It is in- adopts verbatim Article II of the Genocide Convention, cluded, for instance, in the Nuremberg Charter.3 which sets out the definition of genocide, but only par- Conspiracy to commit genocide was first set out in Ar- tially incorporates Article III and excludes conspiracy to ticle III of the 1948 Genocide Convention.4 Experts draft- commit genocide. This is a marked difference from the ing the text intended conspiracy to commit genocide to be statutes of the International Criminal Tribunals for the an inchoate crime under Anglo-American law. -

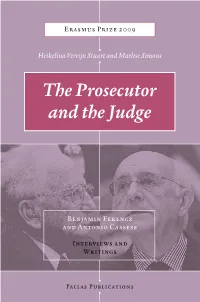

The Prosecutor and the Judge

From Nuremberg and Tokyo Erasmus Prize 2009 to The Hague and Beyond ¶ verrijn stuart | simons Heikelina Verrijn Stuart and Marlise Simons benjamin ferencz, investigator of Nazi war crimes and prosecutor at Nuremberg. Author and lecturer. antonio cassese, first president of the Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and president of the Special Tribunal for Lebanon. The Prosecutor The prestigious Praemium Erasmianum 2009 was awarded to Benjamin Ferencz and Antonio Cassese, who embody the history of international criminal law from and the Judge Nuremberg to The Hague. The Prosecutor and the Judge is a meeting with these two remarkable men through in depth interviews by Heikelina Verrijn Stuart and Marlise Simons about their judge and the e prosecutor ¶ work and ideas, about the war crimes trials, human cruelty, the self-interest of states; about remorse in the courtroom, about restitution and compensation for th victims and about the strength and the limitations of the international courts. Heikelina Verrijn Stuart is a lawyer and philosopher of law who has published extensively on international humanitarian and criminal law and on remorse, revenge and forgiveness. Since 1993 she has followed the international courts and tribunals for radio and television. Marlise Simons is a correspondent for The New York Times, who has written on conflicts and political murder, torture and disappearances from Latin America. For more than a decade, she has reported on international courts and tribunals in The Hague. Benjamin Ferencz and Antonio Cassese Interviews -

Paola Gaeta Curriculum Vitae (Updated July 2015)

Paola Gaeta Curriculum Vitae (updated July 2015) PERSONAL DATA 8 February 1967, Salerno (Italy) Italian, female [email protected] [email protected] EDUCATION PhD, Law, with distinction, European University Institute (1997) Laurea in Scienze Politiche, cum laude, University of Florence, Specialization in International Law (1991) CURRENT POSITION Professor, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies; serving as head of the Department of International Law Adjunct Professor, Law Department, Bocconi University, Milan PREVIOUS APPOINTEMENTS Director of the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights (1 January 2011-31 July 2014) of its LL.M. and Teaching Programmes, Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights (1 October 2007-31 July 2014) Full Professor, Law Faculty, University of Geneva (1.09.2007-31.8.2015) Full Professor (2006-2010) , Associate Professor (2002-2005), and Lecturer (Ricercatore) (1998-2001), University of Florence Adjunct Professor, International Law Department, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies (1.2.2010-31.08.2015) Long-term Visiting Professor, Bocconi University, Milan (1.9.2014-31.8.2015) EDITORIAL’S RESPONSIBILITIES (JOURNALS AND SERIES OF MONOGRAPHS) Editor (with S. Zappalà), Oxford Monographs in International Humanitarian and Criminal Law (Oxford University Press) (as from July 2012) Member of the Board of Editors, Journal of International Criminal Justice (Oxford University Press) as from 2009 Member of the Board of Editors, European Journal of International Law, (Oxford University Press) 2010-2012 OTHER PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES Pro-Bono Member of the Committee of Expert for the International Crimes Evidence Project on Sri Lanka of the Public Interest Advocacy Centre Fall 2013 Pro-bono activity (expert opinion and affidavit), on behalf of the Centre for Justice and Accountability, Samantar case July-October 2011 PAOLA GAETA PAGINA 2 Legal Adviser for the Government of Uruguay Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay case (Argentina v. -

Corrigé Corrected

Corrigé Corrected CR 2014/18 International Court Cour internationale of Justice de Justice THE HAGUE LA HAYE YEAR 2014 Public sitting held on Friday 14 March 2014, at 10 a.m., at the Peace Palace, President Tomka presiding, in the case concerning Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Croatia v. Serbia) ________________ VERBATIM RECORD ________________ ANNÉE 2014 Audience publique tenue le vendredi 14 mars 2014, à 10 heures, au Palais de la Paix, sous la présidence de M. Tomka, président, en l’affaire relative à l’Application de la convention pour la prévention et la répression du crime de génocide (Croatie c. Serbie) ____________________ COMPTE RENDU ____________________ - 2 - Present: President Tomka Vice-President Sepúlveda-Amor Judges Owada Keith Bennouna Skotnikov Cançado Trindade Yusuf Greenwood Xue Donoghue Gaja Sebutinde Bhandari Judges ad hoc Vukas Kreća Registrar Couvreur - 3 - Présents : M. Tomka, président M. Sepúlveda-Amor, vice-président MM. Owada Keith Bennouna Skotnikov Cançado Trindade Yusuf Greenwood Mmes Xue Donoghue M. Gaja Mme Sebutinde M. Bhandari, juges MM. Vukas Kreća, juges ad hoc M. Couvreur, greffier - 4 - The Government of the Republic of Croatia is represented by: Ms Vesna Crnić-Grotić, Professor of International Law, University of Rijeka, as Agent; H.E. Ms Andreja Metelko-Zgombić, Ambassador, Director General for EU Law, International Law and Consular Affairs, Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs, Zagreb, Ms Jana Špero, Head of Sector, Ministry of Justice, Zagreb, Mr. Davorin Lapaš, Professor of International Law, University of Zagreb, as Co-Agents; Mr. James Crawford, A.C., S.C., F.B.A., Whewell Professor of International Law, University of Cambridge, Member of the Institut de droit international, Barrister, Matrix Chambers, London, Mr. -

UNITED NATIONS Case No.: IT-95-16-T Date: 14 January 2000

UNITED NATIONS International Tribunal for the Case No.: IT-95-16-T Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of Date: 14 January 2000 International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia since 1991 Original: English IN THE TRIAL CHAMBER Before: Judge Antonio Cassese, Presiding Judge Richard May Judge Florence Ndepele Mwachande Mumba Registrar: Mrs. Dorothee de Sampayo Garrido-Nijgh Judgement of: 14 January 2000 PROSECUTOR v. Zoran KUPRE[KI], Mirjan KUPRE[KI], Vlatko KUPRE[KI], Drago JOSIPOVI], Dragan PAPI], Vladimir [ANTI], also known as “VLADO” JUDGEMENT The Office of the Prosecutor: Mr. Franck Terrier Mr. Michael Blaxill Counsel for the Accused: Mr. Ranko Radovi}, Mr. Tomislav Pasari}, for Zoran Kupre{ki} Ms. Jadranka Slokovi}-Gluma}, Ms. Desanka Vranjican, for Mirjan Kupre{ki} Mr. Borislav Krajina, Mr. Želimar Par, for Vlatko Kupre{ki} Mr. Luko [u{ak, Ms. Goranka Herljevic, for Drago Josipovi} Mr. Petar Puli{eli}, Ms. Nika Pinter, for Dragan Papi} Mr. Petar Pavkovi}, Mr. Mirko Vrdoljak, for Vladimir Šanti} Case No.: IT-95-16-T 14 January 2000 i CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................... 2 A. The International Tribunal.........................................................................................................................2 B. Procedural Background...............................................................................................................................2 II. THE CHARGES AGAINST -

The Statute of the International Criminal Court: Some Preliminary Reflections

q EJIL 1999 ............................................................................................. The Statute of the International Criminal Court: Some Preliminary Reflections Antonio Cassese* Abstract The author appraises the contribution of the International Criminal Court (ICC) to substantive and procedural international criminal law. He portrays it as a revolutionary innovation. Its substantive features include: a definition of crimes falling within its jurisdiction which is more specific than in existing international law; and impressive detail in spelling out general principles of international criminal law such as actus reus, mens rea, nullum crimen and nulla poena, as well as various forms of international criminal responsibility (for commission of crimes, aiding and abetting, etc.). Certain of the substantive provisions, however, may be considered retrogressive in the light of existing law. These include: the distinction between international and internal armed conflicts, needlessly perpetuated in Article 8; an insufficient prohibition of the use in armed conflict of modern weapons that cause unnecessary suffering or are inherently indiscriminate; the excessively cautious criminalization of war crimes offences; the omission of recklessness as a culpable state of mind at least for some crimes; and excessive breadth given to the defences of mistake of law, superior order and self-defence. The author considers the ICC’s major contribution to be procedural. The Statute has set up a complex judicial body with detailed regulations governing all the stages in the criminal adjudication. The prerequisites to the exercise of jurisdiction, however, depend greatly on the willingness of all states parties concerned in the prosecution to cooperate with the Court. In its present form, the author argues, the Statute is somewhat too deferential to the prerogatives of state sovereignty, a fact which could impair the ICC’s effectiveness. -

UNIVERSALITY of PUNISHMENT Horizons (In Semiotica, 2013); Create to Rule

Unità del sapere giuridico 14 Quaderni di scienze penalistiche e filosofico-giuridiche ANTONIO INCAMPO is Full Professor of Dipartimento di Giurisprudenza We only have to consider the ius commune Philosophy of Law at the University of Bari Università degli Studi di Bari “Aldo Moro” of tenth-century continental Europe (or “Aldo Moro.” In the past, he was Director of the ius gentium of the Romans) to realise the Department of Criminal Law, Criminal that the concept of law has historically Procedural Law and Philosophy of Law at the been undergoing an irreversible process University of Bari, and President of the Degree of maturation, particularly intense in the Courses of the Second Faculty of Law at the twentieth century, towards rational universality. same University. He is author of numerous One central goal of contemporary law, essays on philosophy and semiotics of legal however, which is of paramount importance language. Among his major works are: Sul to the studies in this volume, is that the law Fondamento della Validità Deontica. Identità should not only be supra-national, but also Non-Contraddizione (Bari, 1996), Atto e universally enforceable. Every nation has Funzione. Sistema di Deontica Materiale A obligations to other nations, inevitably with Priori (Bari, 1997), Validità Funzionale di Norme the rise of the modern state, which are not (Bari, 2001), Filosofia del Dovere Giuridico restricted to the defence of national borders, (Bari, 2003, 20122), Ricerche di Filosofia del and which could potentially involve the Diritto, with A.G. Conte, P. Di Lucia, G. Lorini, W. use of force in defence of the common ed. -

The UN International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur: New and Disturbing Findings

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 4 Issue 3 Article 6 December 2009 The UN International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur: New and Disturbing Findings Samuel Totten Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Totten, Samuel (2009) "The UN International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur: New and Disturbing Findings," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 4: Iss. 3: Article 6. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol4/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The UN International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur: New and Disturbing Findings Samuel Totten University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Following a US referral of the Darfur crisis to the United Nations, the UN under- took the UN Commission of Inquiry into Darfur. In late January 2005, following an analysis of the data collected by the UN’s COI team, the UN declared that while it found crimes against humanity had been committed by the government of Sudan (GoS) and the Janjaweed (Arab militia), it did not find evidence that the GoS had perpetrated genocide. Herein, Samuel Totten, argues that a correct analysis of the data collected by the COI team would have been genocide. In addition to offering a critique of the COI’s analysis, Totten is critical of the hurried, unsystematic, and underfunded investigation. -

Universal Human Rights: a Generational History Eric Engle

Annual Survey of International & Comparative Law Volume 12 | Issue 1 Article 10 2006 Universal Human Rights: A Generational History Eric Engle Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/annlsurvey Part of the Human Rights Law Commons Recommended Citation Engle, Eric (2006) "Universal Human Rights: A Generational History," Annual Survey of International & Comparative Law: Vol. 12: Iss. 1, Article 10. Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/annlsurvey/vol12/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Annual Survey of International & Comparative Law by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Engle: Universal Human Rights UNIVERSAL HUMAN RIGHTS: A GENERATIONAL HISTORY ERIC ENGLE· Human rights are universal. Not in the sense of being the same positive laws, at all times and places, but rather as being aspirational goals, at all times and places, and also as containing core values which are indeed universal, such as the right to life (no irrational deprivation of life). His tories of human rights usually propose that the concept has evolved through at least three separate historical waves. This historical account, while roughly accurate, must be clarified as a theoretical construction which corresponds only partially to the historical reality: the rights of women and of non-white persons, in fact, arose relatively late in history. With that qualification, however, the historical description is roughly accurate, and also explains why we can speak of human rights as "uni versal" in a meaningful sense.