Introductory Note

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context

Goettingen Journal of International Law 2 (2010) 3, 871-892 Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context Jessica Liang Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................ 872 A. Introduction .......................................................................................... 872 B. Superior Orders and the Soldier‘s Dilemma ........................................ 872 C. A Brief History of the Superior Orders Defense under International Law ............................................................................................. 874 D. Alternative Degrees of Attributing Criminal Responsibility: Finding the Right Solution to the Soldier‘s Dilemma ..................................... 878 I. Absolute Defense ................................................................................. 878 II. Absolute Liability................................................................................. 880 III.Conditional Liability ............................................................................ 881 1. Manifest Illegality ..................................................................... 881 2. A Reasonableness Standard ...................................................... 885 E. Frontiers of the Defense: Obedience to Civilian Orders? .................... 889 I. Operation under the Rome Statute ....................................................... 889 II. How far should the Defense of Superior Orders -

Nuremberg Academy Annual Report 2018

Annual Report International Nuremberg Principles Academy 1 Imprint The Annual Report 2018 has been Executive Board: published by the International Klaus Rackwitz (Director), Nuremberg Principles Academy. Dr. Viviane Dittrich (Deputy Director) It is available in English, German Edited by: and French and can be ordered Evelyn Müller at [email protected] Layout: or be downloaded on the website Martin Küchle Kommunikationsdesign www.nurembergacademy.org. Photos: Egidienplatz 23 International Nuremberg Principles Academy 90403 Nuremberg, Germany p. 9 Strathmore University, p. 20 Wayamo T + 49 (0) 911.231.10379 Foundation F + 49 (0) 911.231.14020 Printed by: [email protected] Druckwerk oHG Table of Contents 2 Foreword 5 The International Nuremberg Principles Academy 7 A Forum for Dialogue 8 • Events 14 • Network and Cooperation 19 Capacity Building 25 Research 29 Publications and Resources 32 Communications 34 Organization 37 Partners and Sponsors We proudly present the second edition of the Annual Report of the International Nuremberg Principles Academy. It reflects the activities and the achieve ments of the Nuremberg Academy throughout the year of 2018. It was another year of growth for the Nu Foreword remberg Academy with an increased num ber of events and activities at a peak level. Important anniversaries such as the 70th anniversary of the judgment of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo and the 20th anniversary of the adoption of the Rome Statute have been reflected in the Academy’s work and activities. Major international conferences – as far as we can see the largest of their kind, dedicated to these important dates worldwide – were held in Nuremberg in May and in October. -

Nuremberg Icj Timeline 1474-1868

NUREMBERG ICJ TIMELINE 1474-1868 1474 Trial of Peter von Hagenbach In connection with offenses committed while governing ter- ritory in the Upper Alsace region on behalf of the Duke of 1625 Hugo Grotius Publishes On the Law of Burgundy, Peter von Hagenbach is tried and sentenced to death War and Peace by an ad hoc tribunal of twenty-eight judges representing differ- ent local polities. The crimes charged, including murder, mass Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo Grotius, one of the principal rape and the planned extermination of the citizens of Breisach, founders of international law with such works as Mare Liberum are characterized by the prosecution as “trampling under foot (On the Freedom of the Seas), publishes De Jure Belli ac Pacis the laws of God and man.” Considered history’s first interna- (On the Law of War and Peace). Considered his masterpiece, tional war crimes trial, it is noted for rejecting the defense of the book elucidates and secularizes the topic of just war, includ- superior orders and introducing an embryonic version of crimes ing analysis of belligerent status, adequate grounds for initiating against humanity. war and procedures to be followed in the inception, conduct, and conclusion of war. 1758 Emerich de Vattel Lays Foundation for Formulating Crime of Aggression In his seminal treatise The Law of Nations, Swiss jurist Emerich de Vattel alludes to the great guilt of a sovereign who under- 1815 Declaration Relative to the Universal takes an “unjust war” because he is “chargeable with all the Abolition of the Slave Trade evils, all the horrors of the war: all the effusion of blood, the The first international instrument to condemn slavery, the desolation of families, the rapine, the acts of violence, the rav- Declaration Relative to the Universal Abolition of the Slave ages, the conflagrations, are his works and his crimes . -

1. Outline the Scope of the 'Nuremberg Principles'. What Is

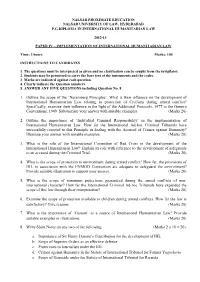

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2012-13 PAPER IV – IMPLEMENTATION OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW Time: 3 hours Marks: 100 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions must be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator. 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. Marks are indicated against each question. 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers. 5. ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS including Question No. 8 1. Outline the scope of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’. What is their influence on the development of International Humanitarian Law relating to protection of Civilians during armed conflict? Specifically, examine their influence in the light of the Additional Protocols, 1977 to the Geneva Conventions, 1949. Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 2. Outline the importance of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ in the implementation of International Humanitarian Law. How far the International Ad-hoc Criminal Tribunals have successfully resorted to this Principle in dealing with the Accused of Crimes against Humanity? Illustrate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 3. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. (Marks 20) 4. What is the scope of protection to environment during armed conflict? How far, the provisions of IHL in association with the ENMOD Convention are adequate to safeguard the environment? Provide suitable illustration to support your answer. -

1. Examine the Impact of the 'Nuremberg Principles' on The

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2009-10 PAPER IV – Implementation of International Humanitarian Law Time: 2 hours and 30 minutes Marks: 75 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions to be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. All questions carry equal marks (15 marks each) 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS 1. Examine the impact of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’ on the development of IHL in the post Geneva Conventions phase. How far, the Nuremberg Principles have facilitated the implementation of the IHL? Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. 2. Examine the scope of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ as an important principle of International humanitarian law. How far this principle has been invoked at the International Plane for the effective implementation of IHL? Support your answer with suitable examples. 3. Write Short Notes on any three of the following a. Importance of Marten’s Clause b. Principle of Complimentarity c. Protections to witnesses during criminal trial d. Scope of War Crimes in the Statute of International Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia e. Scope of Crimes against in the Statute of International Tribunal for Rwanda 4. Examine the scope of ‘Rape’ as interpreted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda committed during the course of Non International Armed Conflict. Refer to leading case laws. 5. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. -

ICC-ASP/11/18 Assembly of States Parties

International Criminal Court ICC-ASP/11/18 Distr.: General Assembly of States Parties 9 November 2012 Original: English Eleventh session The Hague, 14-22 November 2012 Designation of the members of the Advisory Committee on Nominations Note by the Secretariat By resolution ICC-ASP/9/Res.5,1 the Assembly welcomed the report2 adopted by the Bureau pursuant to paragraph 25 of resolution ICC-ASP/9/Res.3 and adopted the recommendations contained therein. It also requested the Bureau to start the process of preparing the election, by the Assembly of States Parties, of the members of the Advisory Committee on nominations of judges of the International Criminal Court in accordance with the terms of reference of the Advisory Committee. Article 36, paragraph 4 (c), of the Rome Statute provides as follows: “(c) The Assembly of States Parties may decide to establish, if appropriate, an Advisory Committee on nominations. In that event, the Committee’s composition and mandate shall be established by the Assembly of States Parties.” The terms of reference of the Advisory Committee on Nominations provide that: “The Committee should be composed of nine members, nationals of States Parties, designated by the Assembly of States Parties by consensus on recommendation made by the Bureau of the Assembly also made by consensus, reflecting the principal legal systems of the world and an equitable geographical representation, as well as a fair representation of both genders, based on the number of States Parties to the Rome Statute.”3 At its 11th meeting, on 1 May 2012, the Bureau fixed the nomination period to run for 12 weeks, from 16 May to 8 August 2012 (Central European Time). -

The Nuremberg Legacy and the International Criminal Court—Lecture in Honor of Whitney R

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University Global Studies Law Review Volume 12 Issue 3 The International Criminal Court At Ten (Symposium) 2013 The Nuremberg Legacy and the International Criminal Court—Lecture in Honor of Whitney R. Harris, Former Nuremberg Prosecutor Hans-Peter Kaul International Criminal Court (ICC) Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies Part of the Courts Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Hans-Peter Kaul, The Nuremberg Legacy and the International Criminal Court—Lecture in Honor of Whitney R. Harris, Former Nuremberg Prosecutor, 12 WASH. U. GLOBAL STUD. L. REV. 637 (2013), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies/vol12/iss3/18 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Global Studies Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NUREMBERG LEGACY AND THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT— LECTURE IN HONOR OF WHITNEY R. HARRIS, FORMER NUREMBERG PROSECUTOR HANS-PETER KAUL∗∗∗ We are assembled today in honor of Whitney R. Harris, a great American, a great advocate of the rule of law and international justice. We are also assembled here today, and tomorrow, to reflect on the International Criminal Court (ICC) and its fight against impunity until the present day. It is quite a noteworthy coincidence that this year we celebrate both the 100th birthday of Whitney R. -

The International Criminal Court Prosecutor Seeks a Warrant Written by Benjamin Schiff

The Politics of Justice: The International Criminal Court Prosecutor seeks a Warrant Written by Benjamin Schiff This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. The Politics of Justice: The International Criminal Court Prosecutor seeks a Warrant https://www.e-ir.info/2008/07/16/the-politics-of-justice-the-international-criminal-court-prosecutor-seeks-a-warrant/ BENJAMIN SCHIFF, JUL 16 2008 There is some irony in the criticism of ICC Chief Prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo for issuing his request for a warrant of arrest for Sudanese President Omar Hassan Ahmad Al Bashir. Approximately two years ago, responding to the request of the Pre-Trial Chamber (PTC I), amicus filings from two distinguished commentators – Judge Antonio Cassese (who had chaired the International Commission of Inquiry into the Sudan1 that reported to the Secretary-General and UN Security Council (UNSC) in early 2005, leading to the UNSC’s March 31 referral of the situation to the ICC), and Judge Louise Arbour (former Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and by 2005 the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights) – indicated that the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) should move more quickly and against high levels of the Sudanese government in order to pressurize it to protect the citizens of Darfur and to be more visibly pursuing justice in the situation.2 Within the wider non-governmental organization (NGO) human rights community, the OTP was criticized for moving too slowly and cautiously. -

The United States Response to Achille Lauro-Questions of Jurisdiction

CONTEMPORARY USES OF FORCE AGAINST TERRORISM: THE UNITED STATES RESPONSE TO A CHILLE LA URO-QUESTIONS OF JURISDICTION AND ITS EXERCISE Jeffrey Allan McCredie* CONTENTS I. FACTUAL BACKGROUND ................................ 436 II. CLAIMS OF JURISDICTION UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW. 437 A. Jurisdiction Over International Crimes .......... 437 B. Crimes Against Humanity ..................... 440 C. The Seizure of the Vessel as an Act of Piracy .. 443 1. United States Practice ..................... 443 2. Piracy Under the Law of Nations .......... 443 3. The Convention on the High Seas ......... 445 4. M odern Piracy ........................... 446 D. Terrorism as an International Crime ........... 450 1. United Nations Efforts. .................... 450 2. Other Modern Efforts ...................... 453 III. CLAIMS TO EXERCISE JURISDICTION BY FORCE ......... 454 A. Current United States Policy .................. 454 B. Restrictions on the Use of Force Under Interna- tional Law ................................... 455 C. Exceptions to the General Prohibitions of the Use of Force ..................................... 457 1. The Right of Self-Defense ................. 457 2. The Doctrine of Intervention and Self-Help. 459 a. Intervention ......................... 459 b. Self-Help ........................... 460 c. The Protection of Nationals Abroad ... 461 d. An Analogy to Hostage Rescue A ttempts ............................ 462 IV. CONCLUSIONS AND PROSPECTS FOR THE FUTURE ....... 465 * Member PA Bar, Assistant District Attorney, Montgomery County, -

The Evolution of Individual Criminal Responsibility Under International Law by EDOARDO GREPPI

RICRSEPTEMBRE IRRCSEPTEMBER 1999 VOL.81 N°835 The evolution of individual criminal responsibility under international law by EDOARDO GREPPI HE international legal provisions on war crimes and crimes against humanity have been adopted and developed within the frame- work of international humanitarian law, or the law of armed Tconflict, a special branch of international law which has its own peculiarities and which has gone through an intense period of growth, evo- lution and consolidation in the last 50 years. The rules of humanitarian law concerning international crimes and responsibility have not always appeared sufEciendy clear. One of the thorniest problems is that relating to the legal nature of international crimes committed by individuals and considered as serious violations of the rules of humanitarian law.1 As regards the traditional tripartition — crimes against EDOARDO GREPPI is Associate Professor of International Law at the University of Turin, Italy, and a member of the International Institute of Humanitarian Law in San Remo. 1 See M. C. Bassiouni/P. Nanda, A Treatise N-Ronzitti- "Crimini intemazionali", Encidopedia on International Criminal Law, Springfield, 1973; 9iuridica, X, 1988; F. Francioni, "Crimini inter- S.G\aser,Droitinternationalpenalconventionnel, mvonati", Digestodelle discipline pubblicistiche, Brussels, 1970-78; G. Sperduti, "Crimini inter- lv- r988- P- 4^4- nazionali", Encidopedia del diritto,Yi, 1962, p. 337; 531 THE EVOLUTION OF INDIVIDUAL CRIMINAL RESPONSIBILITY UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW peace, war crimes and crimes against humanity — this paper will be devoted essentially to the latter two categories, which are more closely linked to the core of international humanitarian law and are of major interest at this tormented end of the twentieth century. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Ambos, Kai. “Article 25. Individual Criminal Responsibility.” In Commentary on the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, edited by Otto Triffterer. Baden- Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, 1999. Ambos, Kai. “Defences.” In General Principles of International Criminal Law, edited by Antonio Cassese, Paola Gaeta and John R.W.D. Jones. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. Ambos, Kai. “What does intent to destroy mean?” International Review of the Red Cross 91 (2009): 833–858. Ambos, Kai, “Grounds Excluding Responsibility (‘Defences’).” In Treatise on Interna- tional Criminal Law: Volume 1: Foundations and General Part, edited by Kai Ambos. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. Ambos, Kai. Treatise on International Criminal Law: Volume I: Foundations and General Part. Oxford Scholarly Authorities on International Law, 2013. Ambos, Kai. Treatise on International Criminal Law: Volume II: The Crimes and Sentenc- ing. Oxford Scholarly Authorities on International Law, 2014. Anggadi, Frances, Greg French and James Potter. “Negotiating the Elements of the Crime of Aggression.” In Crime of Aggression Library: The Travaux Préparatoires of the Crime of Aggression, edited by Stefan Barriga and Claus Kreß. Cambridge: Cam- bridge University Press, 2012. Astill, James. “Strike one.” The Guardian. 2 October 2001. Accessed 20 June 2016. http:// www.theguardian.com/world/2001/oct/02/afghanistan.terrorism3. Badar, Mohamed Elewa. “Drawing the Boundaries of Mens rea in the Jurisprudence of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia.” International Crimi- nal Law Review 6 (2006). Badar, Mohamed Elewa. “The Mental Element in the Rome Statute of the Internation- al Criminal Court: A Commentary from a Comparative Law Perspective.” Criminal Law Forum 19 (2008). -

Conspiracy to Commit Genocide and Its Exclusion from the ICC Statute by SONG Tianying FICHL Policy Brief Series No

POLICY BRIEF SERIES Conspiracy to Commit Genocide and its Exclusion From the ICC Statute By SONG Tianying FICHL Policy Brief Series No. 18 (2014) 1. Introduction fact that in practice genocide is a collective crime, presup- The criminal classification ‘conspiracy’ may denote either posing the collaboration of a greater or smaller number of 6 a substantive crime or a mode of liability. As a substantive persons”. During the subsequent discussion over the crime, it punishes the agreement of two or more persons draft, a number of states that did not have the concept of to commit a crime, irrespective of whether the intended conspiracy in their domestic law pointed out that the pro- crime is committed or not.1 It is generally recognized as a vision needed to be applied according to principles of 7 crime specific to the common law tradition. Conspiracy each penal system. as a form of liability attributes responsibility to co-con- The Statute of the International Criminal Court (‘ICC’) spirators where the intended crime is committed.2 It is in- adopts verbatim Article II of the Genocide Convention, cluded, for instance, in the Nuremberg Charter.3 which sets out the definition of genocide, but only par- Conspiracy to commit genocide was first set out in Ar- tially incorporates Article III and excludes conspiracy to ticle III of the 1948 Genocide Convention.4 Experts draft- commit genocide. This is a marked difference from the ing the text intended conspiracy to commit genocide to be statutes of the International Criminal Tribunals for the an inchoate crime under Anglo-American law.