International Criminal Courts: the Legacy of Nuremberg Benjamin B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16. the Nuremberg Trials: Nazi Criminals Face Justice

fdr4freedoms 1 16. The Nuremberg Trials: Nazi Criminals Face Justice On a ship off the coast of Newfoundland in August 1941, four months before the United States entered World War II, Franklin D. Roosevelt and British prime minister Winston Churchill agreed to commit themselves to “the final destruction of Nazi tyranny.” In mid-1944, as the Allied advance toward Germany progressed, another question arose: What to do with the defeated Nazis? FDR asked his War Department for a plan to bring Germany to justice, making it accountable for starting the terrible war and, in its execution, committing a string of ruthless atrocities. By mid-September 1944, FDR had two plans to consider. Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr. had unexpectedly presented a proposal to the president two weeks before the War Department finished its own work. The two plans could not have been more different, and a bitter contest of ideas erupted in FDR’s cabinet. To execute or prosecute? Morgenthau proposed executing major Nazi leaders as soon as they were captured, exiling other officers to isolated and barren lands, forcing German prisoners of war to rebuild war-scarred Europe, and, perhaps most controversially, Defendants and their counsel in the trial of major war criminals before the dismantling German industry in the highly developed Ruhr International Military Tribunal, November 22, 1945. The day before, all defendants and Saar regions. One of the world’s most advanced industrial had entered “not guilty” pleas and U.S. top prosecutor Robert H. Jackson had made his opening statement. “Despite the fact that public opinion already condemns economies would be left to subsist on local crops, a state their acts,” said Jackson, “we agree that here [these defendants] must be given that would prevent Germany from acting on any militaristic or a presumption of innocence, and we accept the burden of proving criminal acts and the responsibility of these defendants for their commission.” Harvard Law School expansionist impulses. -

Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context

Goettingen Journal of International Law 2 (2010) 3, 871-892 Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context Jessica Liang Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................ 872 A. Introduction .......................................................................................... 872 B. Superior Orders and the Soldier‘s Dilemma ........................................ 872 C. A Brief History of the Superior Orders Defense under International Law ............................................................................................. 874 D. Alternative Degrees of Attributing Criminal Responsibility: Finding the Right Solution to the Soldier‘s Dilemma ..................................... 878 I. Absolute Defense ................................................................................. 878 II. Absolute Liability................................................................................. 880 III.Conditional Liability ............................................................................ 881 1. Manifest Illegality ..................................................................... 881 2. A Reasonableness Standard ...................................................... 885 E. Frontiers of the Defense: Obedience to Civilian Orders? .................... 889 I. Operation under the Rome Statute ....................................................... 889 II. How far should the Defense of Superior Orders -

From the Nuremberg Trials to the Memorial Nuremberg Trials

Presse- und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit Memorium Nürnberger Prozesse Hirschelgasse 9-11 90403 Nürnberg Telefon: 0911 / 2 31-66 89 Telefon: 0911 / 2 31-54 20 Telefax: 0911 / 2 31-1 42 10 E-Mail: [email protected] www.museen.nuernberg.de – Press Release From the Nuremberg Trials to the Memorial Nuremberg Trials Nuremberg’s name is linked with the NSDAP Party Rallies held here between 1933 and 1938 and – Presseinformation with the „Racial Laws“ adopted in 1935. It is also linked with the trials where leading representatives of the Nazi regime had to answer for their crimes in an international court of justice. Between 20 November, 1945, and 1 October, 1946, the International Military Tribunal’s trial of the main war criminals (IMT) was held in Court Room 600 at the Nuremberg Palace of Justice. Between 1946 and 1949, twelve follow-up trials were also held here. Those tried included high- ranking representatives of the military, administration, medical profession, legal system, industry Press Release and politics. History Two years after Germany had unleashed World War II on 1 September, 1939, leading politicians and military staff of the anti-Hitler coalition started to consider bringing to account those Germans responsible for war crimes which had come to light at that point. The Moscow Declaration of 1943 and the Conference of Yalta of February 1945 confirmed this attitude. Nevertheless, the ideas – Presseinformation concerning the type of proceeding to use in the trial were extremely divergent. After difficult negotiations, on 8 August, 1945, the four Allied powers (USA, Britain, France and the Soviet Union) concluded the London Agreement, on a "Charter for The International Military Tribunal", providing for indictment for the following crimes in a trial based on the rule of law: 1. -

The Trial of Paul Touvier

A CENTURY OF GENOCIDES AND JUSTICE: THE TRIAL OF PAUL TOUVIER An Undergraduate Research Scholars Thesis by RACHEL HAGE Submitted to the Undergraduate Research Scholars program at Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the designation as an UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH SCHOLAR Approved by Research Advisor: Dr. Richard Golsan May 2020 Major: International Studies, International Politics and Diplomacy Track TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT .....................................................................................................................................1 Literature Review.....................................................................................................1 Thesis Statement ......................................................................................................1 Theoretical Framework ............................................................................................2 Project Description...................................................................................................2 KEY WORDS ..................................................................................................................................4 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................5 United Nations Rome Statute ..................................................................................5 20th Century Genocide .............................................................................................6 -

Prosecuting Rape As a War Crime in the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Volume 26 Number 1 Article 5 Fall 2000 Rethinking the Spoils of War: Prosecuting Rape as a War Crime in the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia Christin B. Coan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Christin B. Coan, Rethinking the Spoils of War: Prosecuting Rape as a War Crime in the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, 26 N.C. J. INT'L L. 183 (2000). Available at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol26/iss1/5 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rethinking the Spoils of War: Prosecuting Rape as a War Crime in the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This comments is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/ vol26/iss1/5 Rethinking the Spoils of War: Prosecuting Rape as a War Crime in the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia What is wonderful is that we come from all different systems and we are trying to create a system that is acceptable to all. We are doing pretty good thus far. -ICTY Judge Gabrielle Kirk McDonald' For as long as organized human conflict has existed, the specter of wartime rape has loomed as a deplorable and historically unaddressed side effect of war.2 The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY), created to hear cases arising from the conflict in that war-torn area, has had occasion to pass judgment on rape and sexual assault as sanctionable criminal offenses.' This Comment analyzes the ways in which the procedural and evidentiary rules governing the ICTY's treatment of rape have been interpreted and applied in practice. -

Nuremberg Academy Annual Report 2018

Annual Report International Nuremberg Principles Academy 1 Imprint The Annual Report 2018 has been Executive Board: published by the International Klaus Rackwitz (Director), Nuremberg Principles Academy. Dr. Viviane Dittrich (Deputy Director) It is available in English, German Edited by: and French and can be ordered Evelyn Müller at [email protected] Layout: or be downloaded on the website Martin Küchle Kommunikationsdesign www.nurembergacademy.org. Photos: Egidienplatz 23 International Nuremberg Principles Academy 90403 Nuremberg, Germany p. 9 Strathmore University, p. 20 Wayamo T + 49 (0) 911.231.10379 Foundation F + 49 (0) 911.231.14020 Printed by: [email protected] Druckwerk oHG Table of Contents 2 Foreword 5 The International Nuremberg Principles Academy 7 A Forum for Dialogue 8 • Events 14 • Network and Cooperation 19 Capacity Building 25 Research 29 Publications and Resources 32 Communications 34 Organization 37 Partners and Sponsors We proudly present the second edition of the Annual Report of the International Nuremberg Principles Academy. It reflects the activities and the achieve ments of the Nuremberg Academy throughout the year of 2018. It was another year of growth for the Nu Foreword remberg Academy with an increased num ber of events and activities at a peak level. Important anniversaries such as the 70th anniversary of the judgment of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo and the 20th anniversary of the adoption of the Rome Statute have been reflected in the Academy’s work and activities. Major international conferences – as far as we can see the largest of their kind, dedicated to these important dates worldwide – were held in Nuremberg in May and in October. -

Nuremberg Icj Timeline 1474-1868

NUREMBERG ICJ TIMELINE 1474-1868 1474 Trial of Peter von Hagenbach In connection with offenses committed while governing ter- ritory in the Upper Alsace region on behalf of the Duke of 1625 Hugo Grotius Publishes On the Law of Burgundy, Peter von Hagenbach is tried and sentenced to death War and Peace by an ad hoc tribunal of twenty-eight judges representing differ- ent local polities. The crimes charged, including murder, mass Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo Grotius, one of the principal rape and the planned extermination of the citizens of Breisach, founders of international law with such works as Mare Liberum are characterized by the prosecution as “trampling under foot (On the Freedom of the Seas), publishes De Jure Belli ac Pacis the laws of God and man.” Considered history’s first interna- (On the Law of War and Peace). Considered his masterpiece, tional war crimes trial, it is noted for rejecting the defense of the book elucidates and secularizes the topic of just war, includ- superior orders and introducing an embryonic version of crimes ing analysis of belligerent status, adequate grounds for initiating against humanity. war and procedures to be followed in the inception, conduct, and conclusion of war. 1758 Emerich de Vattel Lays Foundation for Formulating Crime of Aggression In his seminal treatise The Law of Nations, Swiss jurist Emerich de Vattel alludes to the great guilt of a sovereign who under- 1815 Declaration Relative to the Universal takes an “unjust war” because he is “chargeable with all the Abolition of the Slave Trade evils, all the horrors of the war: all the effusion of blood, the The first international instrument to condemn slavery, the desolation of families, the rapine, the acts of violence, the rav- Declaration Relative to the Universal Abolition of the Slave ages, the conflagrations, are his works and his crimes . -

1. Outline the Scope of the 'Nuremberg Principles'. What Is

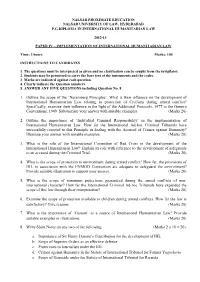

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2012-13 PAPER IV – IMPLEMENTATION OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW Time: 3 hours Marks: 100 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions must be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator. 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. Marks are indicated against each question. 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers. 5. ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS including Question No. 8 1. Outline the scope of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’. What is their influence on the development of International Humanitarian Law relating to protection of Civilians during armed conflict? Specifically, examine their influence in the light of the Additional Protocols, 1977 to the Geneva Conventions, 1949. Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 2. Outline the importance of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ in the implementation of International Humanitarian Law. How far the International Ad-hoc Criminal Tribunals have successfully resorted to this Principle in dealing with the Accused of Crimes against Humanity? Illustrate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 3. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. (Marks 20) 4. What is the scope of protection to environment during armed conflict? How far, the provisions of IHL in association with the ENMOD Convention are adequate to safeguard the environment? Provide suitable illustration to support your answer. -

1. Examine the Impact of the 'Nuremberg Principles' on The

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2009-10 PAPER IV – Implementation of International Humanitarian Law Time: 2 hours and 30 minutes Marks: 75 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions to be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. All questions carry equal marks (15 marks each) 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS 1. Examine the impact of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’ on the development of IHL in the post Geneva Conventions phase. How far, the Nuremberg Principles have facilitated the implementation of the IHL? Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. 2. Examine the scope of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ as an important principle of International humanitarian law. How far this principle has been invoked at the International Plane for the effective implementation of IHL? Support your answer with suitable examples. 3. Write Short Notes on any three of the following a. Importance of Marten’s Clause b. Principle of Complimentarity c. Protections to witnesses during criminal trial d. Scope of War Crimes in the Statute of International Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia e. Scope of Crimes against in the Statute of International Tribunal for Rwanda 4. Examine the scope of ‘Rape’ as interpreted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda committed during the course of Non International Armed Conflict. Refer to leading case laws. 5. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. -

Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg Stephen J

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 46 | Issue 3 Article 4 5-2017 A Court Pure and Unsullied: Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg Stephen J. Sfekas Circuit Court for Baltimore City, Maryland Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Fourteenth Amendment Commons, International Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Sfekas, Stephen J. (2017) "A Court Pure and Unsullied: Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 46 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol46/iss3/4 This Peer Reviewed Articles is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COURT PURE AND UNSULLIED: JUSTICE IN THE JUSTICE TRIAL AT NUREMBERG* Hon. Stephen J. Sfekas** Therefore, O Citizens, I bid ye bow In awe to this command, Let no man live Uncurbed by law nor curbed by tyranny . Thus I ordain it now, a [] court Pure and unsullied . .1 I. INTRODUCTION In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the common understanding was that the Nazi regime had been maintained by a combination of instruments of terror, such as the Gestapo, the SS, and concentration camps, combined with a sophisticated propaganda campaign.2 Modern historiography, however, has revealed the -

The Nuremberg Legacy and the International Criminal Court—Lecture in Honor of Whitney R

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University Global Studies Law Review Volume 12 Issue 3 The International Criminal Court At Ten (Symposium) 2013 The Nuremberg Legacy and the International Criminal Court—Lecture in Honor of Whitney R. Harris, Former Nuremberg Prosecutor Hans-Peter Kaul International Criminal Court (ICC) Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies Part of the Courts Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Hans-Peter Kaul, The Nuremberg Legacy and the International Criminal Court—Lecture in Honor of Whitney R. Harris, Former Nuremberg Prosecutor, 12 WASH. U. GLOBAL STUD. L. REV. 637 (2013), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies/vol12/iss3/18 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Global Studies Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NUREMBERG LEGACY AND THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT— LECTURE IN HONOR OF WHITNEY R. HARRIS, FORMER NUREMBERG PROSECUTOR HANS-PETER KAUL∗∗∗ We are assembled today in honor of Whitney R. Harris, a great American, a great advocate of the rule of law and international justice. We are also assembled here today, and tomorrow, to reflect on the International Criminal Court (ICC) and its fight against impunity until the present day. It is quite a noteworthy coincidence that this year we celebrate both the 100th birthday of Whitney R. -

[email protected] Vichy, Crimes Against Humanity

Henry Rousso Institut d’histoire du temps présent (CNRS, Paris) [email protected] Vichy, Crimes against Humanity, and the Trials for Memory Department of French-Italian, Department of History The University of Texas at Austin Lecture given at 9/11/2003 I would like to begin this talk about the way France coped with its past by making some general statements. Why it may be interesting to study the Vichy legacy, except of course if you are impassionned by French History? Why the history of the memory of the “Dark Years”, the years of the Nazi Occupation, may have some interest for other periods or other situations, in contemporary history? Why to study preciseley how the representations of the past or the behaviour towards the past has evolved from 1944, the Liberation, to the present days, may have a universal meaning ? We can propose several answers : - We may learn a lot in studying the “Dark years” because it’s a period in which a great power, the second world power at that time in terms of political and economic influence, collapsed in six weeks, after a brutal and unexpected agression against its territory. The panic of the defeat, the disarray coming from the vanishing of the State and of other authorities, led to a strong support for a dictatorship, the Vichy Regime, which abolished most of the political rights. The new regime, using the fear of most of the population, declared that France was no more a Republic, and that she had a lot of ennemies : not the Nazi Occupiers, but the Jews, the Foreigners, the Free- Masons, all kind of opponents: in short, for Vichy, one of the result of the defeat, ennemies were at home.