An Absence of Accountability for the My Lai Massacre Jeannine Davanzo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catering to the Silent Majority the My Lai Massacre As a Media Challenge

JANA TOPPE Catering to the silent majority The My Lai massacre as a media challenge Free University of Berlin 10.10.2011 Intensive Program: "Coming Together or Coming Apart? Europe and the United States in the Sixties" September 12 – 24, 2011 Session 6: Lessons of Vietnam and Military Reform Session Chair: Professor Dr. Mark Meigs, Université de Paris-Diderot Table of contents 1 Introduction…………………………………………………..…1 2 Vietnam, the administrations and the media…………….….…..2 2.1 Bone of contention: media coverage of Cam Ne…….……..2 2.2 Nixon, Agnew and the troubles of television………………4 2.3 Expendable lives: Media dehumanization………...………..7 3 Uncovering the atrocities of My Lai……………………….….10 3.1 The media‟s role in publishing the massacre – a tale of hesitancy and caution……………………………....11 3.2 Source: “The My Lai Massacre” - Time, Nov. 28, 1969….17 4 Conclusion…………………………………………………….19 5 Bibliography…………………………………………………..22 5.1 Sources……………………………………………...……..22 5.2 Secondary Literature………………………………..……..22 6 Appendix………………………………………………………23 Jana Toppe 1 Catering to the silent majority 1. Introduction In March 1968, the men of Charlie Company entered the village of My Lai under the command of First Lieutenant William Calley with the objective to „search and destroy‟ the Viet Cong believed to reside there. The village was instead populated by unarmed South Vietnamese civilians, mostly women and children, who were then massacred by Charlie Company. The incident was kept under wraps by the military for a year until an investigative journalist, Seymour Hersh, uncovered the story in 1969. The revelation of the My Lai cover-up and the expanding press coverage was not the watershed moment or turning point in press coverage as one may be tempted to think. -

Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context

Goettingen Journal of International Law 2 (2010) 3, 871-892 Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context Jessica Liang Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................ 872 A. Introduction .......................................................................................... 872 B. Superior Orders and the Soldier‘s Dilemma ........................................ 872 C. A Brief History of the Superior Orders Defense under International Law ............................................................................................. 874 D. Alternative Degrees of Attributing Criminal Responsibility: Finding the Right Solution to the Soldier‘s Dilemma ..................................... 878 I. Absolute Defense ................................................................................. 878 II. Absolute Liability................................................................................. 880 III.Conditional Liability ............................................................................ 881 1. Manifest Illegality ..................................................................... 881 2. A Reasonableness Standard ...................................................... 885 E. Frontiers of the Defense: Obedience to Civilian Orders? .................... 889 I. Operation under the Rome Statute ....................................................... 889 II. How far should the Defense of Superior Orders -

Law of War Workshop Deskbook

INTERNATIONAL AND OPERATIONAL LAW DEPARTMENT THE JUDGE ADVOCATE GENERAL'S SCHOOL, U.S. ARMY CHARLOTTESVILLE, VIRGINIA LAW OF WAR WORKSHOP DESKBOOK CDR Brian J. Bill, JAGC, USN Editor Contributing Authors CDR Brian J. Bill, JAGC, USN MAJ Geoffrey S. Corn, JA, USA LT Patrick J. Gibbons, JAGC, USN LtCol Michael C. Jordan, USMC MAJ Michael 0. Lacey, JA, USA MAJ Shannon M. Morningstar, JA, USA MAJ Michael L. Smidt, JA, USA All of the faculty who have served with and before us and contributed to the literature in the field of the Law of War June 2000 7066 ACLU-RDI 1096 p.1 DOD 004280 ii 7067 ACLU-RDI 1096 p.2 DOD 004281 INTERNATIONAL AND OPERATIONAL LAW DEPARTMENT THE JUDGE ADVOCATE GENERAL'S SCHOOL CHARLOTTESVILLE, VIRGINIA LAW OF WAR WORKSHOP DESKBOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS Major Treaties Governing Land Warfare iv List of Append ices vii History of the Law of War 1 Legal Bases for the Use of Force 13 Legal Framework of the Law of War 25 The 1949 Convention on Wounded and Sick in the Field 49 Prisoners of War and Detainees 69 Protection of Civilians During Armed Conflict 123 Means and Methods of Warfare 149 War Crimes and Command Responsibility 183 The Law of War & Operations Other Than War 219 The Law of War: Methods of Instruction 255 iii 7068 ACLU-RDI 1096 p.3 DOD 004282 iv 7069 ACLU-RDI 1096 p.4 DOD 004283 MAJOR TREATIES GOVERNING LAND WARFARE Abbreviated Name Full Name GWS/lst GC Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field, 12 August 1949, DA Pam 27-1. -

Nuremberg and Beyond: Jacob Robinson, International Lawyer

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 39 Number 1 Special Edition: The Nuremberg Laws Article 12 and the Nuremberg Trials Winter 2017 Nuremberg and Beyond: Jacob Robinson, International Lawyer Jonathan Bush Columbia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Recommended Citation Jonathan Bush, Nuremberg and Beyond: Jacob Robinson, International Lawyer, 39 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 259 (2017). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol39/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUSH MACRO FINAL*.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 1/24/17 7:22 PM Nuremberg and Beyond: Jacob Robinson, International Lawyer JONATHAN A. BUSH* Jacob Robinson (1889–1977) was one of the half dozen leading le- gal intellectuals associated with the Nuremberg trials. He was also argu- ably the only scholar-activist who was involved in almost every interna- tional criminal law and human rights battle in the two decades before and after 1945. So there is good reason for a Nuremberg symposium to include a look at his remarkable career in international law and human rights. This essay will attempt to offer that, after a prefatory word about the recent and curious turn in Nuremberg scholarship to biography, in- cluding of Robinson. -

My Lai Massacre 1 My Lai Massacre

My Lai Massacre 1 My Lai Massacre Coordinates: 15°10′42″N 108°52′10″E [1] My Lai Massacre Thảm sát Mỹ Lai Location Son My village, Son Tinh District of South Vietnam Date March 16, 1968 Target My Lai 4 and My Khe 4 hamlets Attack type Massacre Deaths 347 according to the U.S Army (not including My Khe killings), others estimate more than 400 killed and injuries are unknown, Vietnamese government lists 504 killed in total from both My Lai and My Khe Perpetrators Task force from the United States Army Americal Division 2LT. William Calley (convicted and then released by President Nixon to serve house arrest for two years) The My Lai Massacre (Vietnamese: thảm sát Mỹ Lai [tʰɐ̃ːm ʂɐ̌ːt mǐˀ lɐːj], [mǐˀlɐːj] ( listen); /ˌmiːˈlaɪ/, /ˌmiːˈleɪ/, or /ˌmaɪˈlaɪ/)[2] was the Vietnam War mass murder of between 347 and 504 unarmed civilians in South Vietnam on March 16, 1968, by United States Army soldiers of "Charlie" Company of 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, 11th Brigade of the Americal Division. Victims included women, men, children, and infants. Some of the women were gang-raped and their bodies were later found to be mutilated[3] and many women were allegedly raped prior to the killings.[] While 26 U.S. soldiers were initially charged with criminal offenses for their actions at Mỹ Lai, only Second Lieutenant William Calley, a platoon leader in Charlie Company, was convicted. Found guilty of killing 22 villagers, he was originally given a life sentence, but only served three and a half years under house arrest. -

Nuremberg Academy Annual Report 2018

Annual Report International Nuremberg Principles Academy 1 Imprint The Annual Report 2018 has been Executive Board: published by the International Klaus Rackwitz (Director), Nuremberg Principles Academy. Dr. Viviane Dittrich (Deputy Director) It is available in English, German Edited by: and French and can be ordered Evelyn Müller at [email protected] Layout: or be downloaded on the website Martin Küchle Kommunikationsdesign www.nurembergacademy.org. Photos: Egidienplatz 23 International Nuremberg Principles Academy 90403 Nuremberg, Germany p. 9 Strathmore University, p. 20 Wayamo T + 49 (0) 911.231.10379 Foundation F + 49 (0) 911.231.14020 Printed by: [email protected] Druckwerk oHG Table of Contents 2 Foreword 5 The International Nuremberg Principles Academy 7 A Forum for Dialogue 8 • Events 14 • Network and Cooperation 19 Capacity Building 25 Research 29 Publications and Resources 32 Communications 34 Organization 37 Partners and Sponsors We proudly present the second edition of the Annual Report of the International Nuremberg Principles Academy. It reflects the activities and the achieve ments of the Nuremberg Academy throughout the year of 2018. It was another year of growth for the Nu Foreword remberg Academy with an increased num ber of events and activities at a peak level. Important anniversaries such as the 70th anniversary of the judgment of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo and the 20th anniversary of the adoption of the Rome Statute have been reflected in the Academy’s work and activities. Major international conferences – as far as we can see the largest of their kind, dedicated to these important dates worldwide – were held in Nuremberg in May and in October. -

Nuremberg Icj Timeline 1474-1868

NUREMBERG ICJ TIMELINE 1474-1868 1474 Trial of Peter von Hagenbach In connection with offenses committed while governing ter- ritory in the Upper Alsace region on behalf of the Duke of 1625 Hugo Grotius Publishes On the Law of Burgundy, Peter von Hagenbach is tried and sentenced to death War and Peace by an ad hoc tribunal of twenty-eight judges representing differ- ent local polities. The crimes charged, including murder, mass Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo Grotius, one of the principal rape and the planned extermination of the citizens of Breisach, founders of international law with such works as Mare Liberum are characterized by the prosecution as “trampling under foot (On the Freedom of the Seas), publishes De Jure Belli ac Pacis the laws of God and man.” Considered history’s first interna- (On the Law of War and Peace). Considered his masterpiece, tional war crimes trial, it is noted for rejecting the defense of the book elucidates and secularizes the topic of just war, includ- superior orders and introducing an embryonic version of crimes ing analysis of belligerent status, adequate grounds for initiating against humanity. war and procedures to be followed in the inception, conduct, and conclusion of war. 1758 Emerich de Vattel Lays Foundation for Formulating Crime of Aggression In his seminal treatise The Law of Nations, Swiss jurist Emerich de Vattel alludes to the great guilt of a sovereign who under- 1815 Declaration Relative to the Universal takes an “unjust war” because he is “chargeable with all the Abolition of the Slave Trade evils, all the horrors of the war: all the effusion of blood, the The first international instrument to condemn slavery, the desolation of families, the rapine, the acts of violence, the rav- Declaration Relative to the Universal Abolition of the Slave ages, the conflagrations, are his works and his crimes . -

BOOK REVIEW: Telford Taylor: Courts of Terror Paul Sherman

Brooklyn Journal of International Law Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 6 1976 BOOK REVIEW: Telford Taylor: Courts of Terror Paul Sherman Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil Recommended Citation Paul Sherman, BOOK REVIEW: Telford Taylor: Courts of Terror, 3 Brook. J. Int'l L. (1976). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol3/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. BOOK REVIEW Courts of Terror. TELFORD TAYLOR. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1976. Pp. xi, 184. $6.95. New York: Vintage Books (Random House), 1976. Pp. xi, 184. $1.65 (pap.). Reviewed by Paul Sherman* In Courts of Terror, Professor Telford Taylor has produced a work of advocacy with a two-fold purpose: to create "an account of the prostitution of Soviet justice to serve State ends,"' and to publicize this failure of justice in order to "aid or comfort the victims of these abuses, and their friends and relatives."' He achieves the first goal, in large part, by describing his efforts and those of a number of attorneys and law professors to secure the release of twenty-three prisoners in the Soviet Union. In so doing, he describes the unusual procedures and occasionally extraordi- nary application of criminal provisions under which these prison- ers were convicted. Whether publication of this work will achieve his second goal is a subjective judgment, but as he notes in Chap- ter 10, disclosure may serve to "systematize the spreading of in- formation about these cases" and continue whatever momentum 3 has been achieved. -

1. Outline the Scope of the 'Nuremberg Principles'. What Is

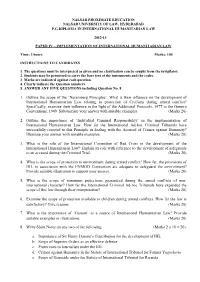

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2012-13 PAPER IV – IMPLEMENTATION OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW Time: 3 hours Marks: 100 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions must be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator. 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. Marks are indicated against each question. 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers. 5. ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS including Question No. 8 1. Outline the scope of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’. What is their influence on the development of International Humanitarian Law relating to protection of Civilians during armed conflict? Specifically, examine their influence in the light of the Additional Protocols, 1977 to the Geneva Conventions, 1949. Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 2. Outline the importance of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ in the implementation of International Humanitarian Law. How far the International Ad-hoc Criminal Tribunals have successfully resorted to this Principle in dealing with the Accused of Crimes against Humanity? Illustrate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 3. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. (Marks 20) 4. What is the scope of protection to environment during armed conflict? How far, the provisions of IHL in association with the ENMOD Convention are adequate to safeguard the environment? Provide suitable illustration to support your answer. -

1. Examine the Impact of the 'Nuremberg Principles' on The

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2009-10 PAPER IV – Implementation of International Humanitarian Law Time: 2 hours and 30 minutes Marks: 75 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions to be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. All questions carry equal marks (15 marks each) 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS 1. Examine the impact of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’ on the development of IHL in the post Geneva Conventions phase. How far, the Nuremberg Principles have facilitated the implementation of the IHL? Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. 2. Examine the scope of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ as an important principle of International humanitarian law. How far this principle has been invoked at the International Plane for the effective implementation of IHL? Support your answer with suitable examples. 3. Write Short Notes on any three of the following a. Importance of Marten’s Clause b. Principle of Complimentarity c. Protections to witnesses during criminal trial d. Scope of War Crimes in the Statute of International Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia e. Scope of Crimes against in the Statute of International Tribunal for Rwanda 4. Examine the scope of ‘Rape’ as interpreted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda committed during the course of Non International Armed Conflict. Refer to leading case laws. 5. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. -

The Nuremberg Legacy and the International Criminal Court—Lecture in Honor of Whitney R

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University Global Studies Law Review Volume 12 Issue 3 The International Criminal Court At Ten (Symposium) 2013 The Nuremberg Legacy and the International Criminal Court—Lecture in Honor of Whitney R. Harris, Former Nuremberg Prosecutor Hans-Peter Kaul International Criminal Court (ICC) Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies Part of the Courts Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Hans-Peter Kaul, The Nuremberg Legacy and the International Criminal Court—Lecture in Honor of Whitney R. Harris, Former Nuremberg Prosecutor, 12 WASH. U. GLOBAL STUD. L. REV. 637 (2013), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies/vol12/iss3/18 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Global Studies Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NUREMBERG LEGACY AND THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT— LECTURE IN HONOR OF WHITNEY R. HARRIS, FORMER NUREMBERG PROSECUTOR HANS-PETER KAUL∗∗∗ We are assembled today in honor of Whitney R. Harris, a great American, a great advocate of the rule of law and international justice. We are also assembled here today, and tomorrow, to reflect on the International Criminal Court (ICC) and its fight against impunity until the present day. It is quite a noteworthy coincidence that this year we celebrate both the 100th birthday of Whitney R. -

Nazi Medicine and the Nuremberg Trials Also by Paul Julian Weindling

Nazi Medicine and the Nuremberg Trials Also by Paul Julian Weindling HEALTH, RACE AND GERMAN POLITICS BETWEEN NATIONAL UNIFICATION AND NAZISM, 1870–1945 EPIDEMICS AND GENOCIDE IN EASTERN EUROPE, 1890–1945 Nazi Medicine and the Nuremberg Trials From Medical War Crimes to Informed Consent Paul Julian Weindling © Paul Julian Weindling 2004 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2004 978-1-4039-3911-1 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2004 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-0-230-50700-5 ISBN 978-0-230-50605-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230506053 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources.