Stewardship Land and DOC - the Beginning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Zealand Azette

Issue No. 182 • 3913 The New Zealand azette WELLINGTON: THURSDAY, 18 OCTOBER 1990 Contents Government Notices 3914 Authorities and Other Agencies of State Notices None Land Notices 3922 Regulation Summary 3943 General Section 3944 Using the Gazette The New Zealand Gazette, the official newspaper of the Closing time for lodgment of notices at the Gazette Office: Government of New , Zealand, is published weekly on 12 noon on Tuesdays prior to publication (except for holiday Thursdays. Publishing time is 4 p.m. periods when special advice of earlier closing times will be Notices for publication and related correspondence should be given). addressed to: Notices are accepted for publication in the next available issue, Gazette Office, unless otherwise specified. Department of Internal Affairs, P.O. Box 805, Notices being submitted for publication must be a reproduced Wellington. copy of the original. Dates, proper names and signatures are Telephone (04) 738 699 to be shown clearly. A covering instruction setting out require Facsimile (04) 499 1865 ments must accompany all notices. or lodged at the Gazette Office, Seventh Floor, Dalmuir Copy will be returned unpublished if not submitted in House, 114 The Terrace, Wellington. accordance with these requirements. 3914 NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 182 Availability Government Buildings, 1 George Street, Palmerston North. The New Zealand Gazette is available on subscription from the Government Printing Office Publications Division or over the Cargill House, 123 Princes Street, Dunedin. counter from Government Bookshops at: Housing Corporation Building, 25 Rutland Street, Auckland. Other issues of the Gazette: 33 Kings Street, Frankton, Hamilton. Commercial Edition-Published weekly on Wednesdays. -

Tomorrow's Schools 20 Years On

Thinking research Tomorrow’s Schools 20 years on... Edited by John Langley Tomorrow’s Schools 20 years on... Edited by John Langley Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 CHAPTER 1 Dr. John Langley 5 Introduction CHAPTER 2 Harvey McQueen 19 Towards a covenant CHAPTER 3 Wyatt Creech 29 Twenty years on CHAPTER 4 Howard Fancy 39 Re-engineering the shifts in the system CHAPTER 5 Elizabeth Eppel 51 Curriculum, teaching and learning: A celebratory review of a very complex and evolving landscape CHAPTER 6 Barbara Disley 63 Can we dare to think of a world without special education? CHAPTER 7 Terry Bates 79 National mission or mission improbable? CHAPTER 8 Brian Annan 91 Schooling improvement since Tomorrow’s Schools CHAPTER 9 Margaret Bendall 105 A leadership perspective Published by Cognition Institute, 2009. ISBN: 978-0-473-15955-9 CHAPTER 10 John Hattie 121 ©Cognition Institute, 2009. Tomorrow’s Schools - yesterday’s news: The quest for a new metaphor All rights reserved. No portion of this publication, printed or CHAPTER 11 Cathy Wylie 135 electronic, may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without Getting more from school self-management the express written consent of the publisher. For more information, email [email protected] CHAPTER 12 Phil Coogan and Derek Wenmoth 149 www.cognitioninstitute.org Tomorrow’s Web for our future learning 1 Acknowledgements The Cognition Education Research Trust (CERT) has a growing network of people and organisations participating in and contributing to the achievement of our philanthropic purposes. There are many who have enabled and contributed to this first thought leader publication on ‘Tomorrow’s Schools Twenty Years On’. -

Is There a Civil Religious Tradition in New Zealand

The Insubstantial Pageant: is there a civil religious tradition in New Zealand? A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Religious Studies in the University of Canterbury by Mark Pickering ~ University of Canterbury 1985 CONTENTS b Chapter Page I (~, Abstract Preface I. Introduction l Plato p.2 Rousseau p.3 Bellah pp.3-5 American discussion on civil religion pp.S-8 New Zealand discussion on civil religion pp.S-12 Terms and scope of study pp.l2-14 II. Evidence 14 Speeches pp.lS-25 The Political Arena pp.25-32 Norman Kirk pp.32-40 Waitangi or New Zealand Day pp.40-46 Anzac Day pp.46-56 Other New Zealand State Rituals pp.56-61 Summary of Chapter II pp.6l-62 III. Discussion 63 Is there a civil religion in New Zealand? pp.64-71 Why has civil religion emerged as a concept? pp.71-73 What might be the effects of adopting the concept of civil religion? pp.73-8l Summary to Chapter III pp.82-83 IV. Conclusion 84 Acknowledgements 88 References 89 Appendix I 94 Appendix II 95 2 3 FEB 2000 ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned with the concept of 'civil religion' and whether it is applicable to some aspects of New zealand society. The origin, development and criticism of the concept is discussed, drawing on such scholars as Robert Bellah and John F. Wilson in the United States, and on recent New Zealand commentators. Using material such as Anzac Day and Waitangi Day commemorations, Governor-Generals' speeches, observance of Dominion Day and Empire Day, prayers in Parliament, the role of Norman Kirk, and other related phenomena, the thesis considers whether this 'evidence' substantiates the existence of a civil religion. -

Friend Or Ally? a Question for New Zealand

.......... , ---~ MeN AIR PAPERS NUMBER T\\ ELVE FRIEND OR ALLY? A QUESTION FOR NEW ZEALAND By EWAN JAMIESON THE INSTI FUTE FOR NATIONAL SI'R-~TEGIC STUDIES ! I :. ' 71. " " :~..? ~i ~ '" ,.Y:: ;,i:,.i:".. :..,-~.~......... ,,i-:i:~: .~,.:iI- " yT.. -.~ .. ' , " : , , ~'~." ~ ,?/ .... ',~.'.'.~ ..~'. ~. ~ ,. " ~:S~(::!?- ~,i~ '. ? ~ .5" .~.: -~:!~ ~:,:i.. :.~ ".: :~" ;: ~:~"~',~ ~" '" i .'.i::.. , i ::: .',~ :: .... ,- " . ".:' i:!i"~;~ :~;:'! .,"L': ;..~'~ ',.,~'i:..~,~'"~,~: ;":,:.;;, ','" ;.: i',: ''~ .~,,- ~.:.~i ~ . '~'">.'.. :: "" ,-'. ~:.." ;';, :.~';';-;~.,.";'."" .7 ,'~'!~':"~ '?'""" "~ ': " '.-."i.:2: i!;,'i ,~.~,~I~out ;popular: ~fo.rmatwn~ .o~~'t,he~,,:. "~.. " ,m/e..a~ tg:,the~6w.erw!~chi~no.wtetl~e.~gi..~e~ ;~i:~.::! ~ :: :~...i.. 5~', '+~ :: ..., .,. "'" .... " ",'.. : ~'. ,;. ". ~.~.~'.:~.'-? "-'< :! :.'~ : :,. '~ ', ;'~ : :~;.':':/.:- "i ; - :~:~!II::::,:IL:.~JmaiegMad}~)~:ib;:, ,?T,-. B~;'...-::', .:., ,.:~ .~ 'z • ,. :~.'..." , ,~,:, "~, v : ", :, -:.-'": ., ,5 ~..:. :~i,~' ',: ""... - )" . ,;'~'.i "/:~'-!"'-.i' z ~ ".. "', " 51"c, ' ~. ;'~.'.i:.-. ::,,;~:',... ~. " • " ' '. ' ".' ,This :iis .aipul~ ~'i~gtin~e ..fdi;:Na~i~real..Sfi'~te~ie.'Studi'~ ~It ;is, :not.i! -, - .... +~l~ase,~ad.~ p,g, ,,.- .~, . • ,,. .... .;. ...~,. ...... ,._ ,,. .~ .... ~;-, :'-. ,,~7 ~ ' .~.: .... .,~,~.:U7 ,L,: :.~: .! ~ :..!:.i.i.:~i :. : ':'::: : ',,-..-'i? -~ .i~ .;,.~.,;: ~v~i- ;. ~, ~;. ' ~ ,::~%~.:~.. : ..., .... .... -, ........ ....... 1'-.~ ~:-~...%, ;, .i-,i; .:.~,:- . eommenaati6'r~:~xpregseff:or ;ii~iplie'd.:;~ifl~in.:iat~ -:: -

Spring Fling

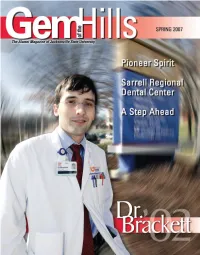

insurance administrator to human resources of the manager, all providing free services to GemThe Alumni Magazine of JacksonvilleHills State University deserving children with Medicaid or ALL- Vol. XIII, No. 2 KIDS insurance. Additional details about the JSU President dreams the center has and the ones they fulfill William A. Meehan, Ed.D., ’72/’76 are located on page 12. Vice President for Institutional Many patients at Erlanger Hospital in Advancement Chattanooga, Tenn. are also benefiting from Joseph A. Serviss, ’69/’75 a JSU alumnus thanks to the skills of Dr. Alumni Association President Stephen Brackett. The feature story on page Sarah Ballard,’69/’75/’82 15 tracks Brackett’s life from his decision to Director of Alumni Affairs and Editor attend JSU to his current life as a hospital Kaci Ogle, ’95/’04 resident. Art Director With a “STEP” in the right direction, Mary Smith, ’93 JSU’s College of Nursing and Health Sciences Staff Artists Dr. William A. Meehan, President Strategic Teaching for Enhanced Professional Erin Hill, ’01/’05 Preparation Program (page 18) is succeeding Rusty Hill in helping licensed RNs obtain higher Graham Lewis Dear Alumni, education goals while still fulfilling personal Copyeditor/Proofreader and occupational duties. Sybil Roark tells Gem Erin Chupp, ’05 In this issue, JSU alumni in healthcare how she returned to JSU for her master’s in Gloria Horton professions and the College of Nursing and nursing while working and raising children. In Staff Writers Health Sciences are highlighted as one of this article she explains how she searched for “a Al Harris, ’81/’91 the outstanding sectors of Jacksonville State quality education” and why JSU had “the best Anne Muriithi University. -

Methodist Conference 2016 Te Háhi Weteriana O Aotearoa

Methodist Conference 2016 Te Háhi Weteriana O Aotearoa CONFERENCE SUMMARY ̴ Moored to Christ, Moving into Mission ̴ The Annual Conference of the Methodist Church of New Zealand met at Wesley College in Paerata, Auckland from Saturday 1 October until Wednesday 5 October 2016 The intention of this record is to provide Conference delegates with summary material to report back to their congregations. This needs to be read in conjunction with the Conference sheets, where full lists of people involved, roles, and appointments will be found. That material and the formal record of decisions and minutes taken by Conference secretaries takes precedence over these more informal notes, for historical and legal purposes! Full proceedings and formal records of conference are available on the Methodist website, http://www.methodist.org.nz/conference/2016 Overseas Guests of Conference included: Rev Tevita Banivanua, President, Methodist Church in Fiji Rev Colleen Geyer, General Secretary, Uniting Church in Australia Rev Prof. Robert Gribbon, Official Representative, Uniting Church in Australia Rev Sandy Boyce (Deacon), Presidnet DIAKONIA World Federation, Uniting Church in Australia Rev Wilfred Kurepitu, Moderator, Uniting Church in Solomon Islands Rev Dr Finau ‘Ahio, President, Free Wesleyan Church of Tonga Rev Bill Mullally, President, Methodist Church of Ireland Rev Masunu Utumapu, Superintendent Auckland South Synod for Methodist Church in Samoa Page 1 Observers from Other New Zealand Churches: Sr. Sian Owen, Pompallier Diocesan Centre, Roman Catholic -

Timing Is Everything

Chapter 2 The ANZACS, Part 1—The Frigate that wasn’t a Frigate As long ago as 1954 the cost of replacement frigates had been an issue. Almost a quarter of a century later, the 1978 Defence Review made the observation that `the high costs of acquiring and maintaining modern naval ships and systems compounds the difficulty of reaching decisions which will adequately provide for New Zealand's future needs at sea'.1 Indeed `extensive enquiries to find a replacement for HMNZS Otago made it clear that the cost of a new frigate had gone beyond what New Zealand could afford'.2 This observation led to the serious consideration of converting the Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN) to a coast guard service, but the Government rejected the notion on the basis that, although a coast guard could carry out resource protection tasks, it would mean the end of any strategic relationship with our ANZUS Treaty partners, and the RNZN would no longer be able to operate as a military force. The Chief of Naval Staff, Rear Admiral Neil D. Anderson, said that the New Zealand Government's commitment to maintaining a professional fighting navy was `a magnificent shot in the arm for everyone in the Navy'.3 The Government remained committed to a compact multi-purpose navy, and calculated that a core operational force of three ships would be the minimum necessary force. These ships were to be the Leander-class frigates HMNZS Waikato and HMNZS Canterbury (commissioned in 1966 and 1971 respectively), and the older Type 12 frigate HMNZS Otago. -

(No. 16)Craccum-1987-061-016.Pdf

T WANTED ST RECOVERY OR ALIVE Sts tl heir res V * , ALSO INSIDE:- ' | # i — Greenpeace on Ice — Crowded House — A World Without Balance — Referendum t. ) : Results J Volume 61 Issue 16 With the release of the Labour Government's policy on education, we see a well executed side-step F e a tu re s away from the issue of user pays in education. Their education policy Trapped in a World itself could be considered as a 'neither confirm nor deny' policy on cost recovery. Though Lange and Without Balance 3 Russell Marshall recently said that Labour has no intention of im l do Einstein, plementing cost recovery in educa S to p Press tion in the near future can we Monet, and Referendum Results believe them, and what exactly is It seems that AUSA Exec has voted (tehurch have in < the near future? Remember the last against the march by a vote of four surface one \ 4 to three. The fourth vote being iculty express election when Labour PROMISED US els... eccentric a living bursary and a fully subsidis Chair's casting vote. What does that, and for Day of Action ed job scheme. They abolished the mean? ter, they are all subsidised job scheme altogether Stop Press le with right bi 7 and have you had a look at your examine the bank balance lately? It seems that some individuals is clear that i Greenpeace on Ice It seems National are just as bad. have decided that the isue is too other feature: Their policy though pledging ac important and have decided to These ar 11 cess to education for all, introduces organise the march with their own the possibility of loans if you study funds. -

The Life and Times of Norman Kirk by David Grant. Auckland: Random House New Zealand, 2014

The Mighty Totara: The Life and Times of Norman Kirk By David Grant. Auckland: Random House New Zealand, 2014. ISBN: 9781775535799 Reviewed by Elizabeth McLeay Norman Kirk left school ‘at the end of standard six with a Proficiency Certificate in his pocket’ (p. 26). He was twelve years old. At the time he entered Parliament, he was a stationary engine driver, an occupation much mocked by the opposing side of New Zealand politics. Kirk was one of the last two working-class prime ministers, the other being Mike Moore, briefly in office during 1990. Not that all prime ministers have had had privileged childhoods: the state house to successful entrepreneur story with its varying narratives has been a continuing leadership marketing theme. But, apart from Moore and Jim Bolger (National Prime Minister between 1990 and 1997), who left school at 15 to work on the family farm—and who owned his own farm by the time he entered Parliament—other New Zealand prime ministers, whether Labour or National, had at least some tertiary education. The early hardship of Kirk’s life, combined with his lifelong appetite for learning shown in the ‘voluminous reading he undertook each week’ (p. 29) strongly influenced his view of politics and indeed his views of the proper role of a political leader. Kirk believed that he must represent the people from whom he came. In this welcome new biography David Grant perceptively relates the moving tale of Kirk’s early life and the extraordinary tale of this remarkable leader’s political career. The author tells us that the ‘essence of this book is an examination of Kirk’s political leadership’ (p.9). -

Changing Skills for a Changing World: Recommendations for Adult Literacy Policy in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Occasional Paper Series. INSTITUTION New Zealand Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 456 219 CE 082 155 AUTHOR Johnson, Alice H. TITLE Changing Skills for a Changing World: Recommendations for Adult Literacy Policy in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Occasional Paper Series. INSTITUTION New Zealand Dept. of Labour, Wellington. REPORT NO OP-2000/2 ISSN ISSN-1173-8782 PUB DATE 2000-10-00 NOTE 116p.; Sponsored by the Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy. Support also provided by Skill New Zealand and the Industry Training Federation. Produced by the Labour Market Policy Group. AVAILABLE FROM Labour Market Policy Group, New Zealand Department of Labour, P.O. Box 3705, Wellington, New Zealand ($10 New Zealand) .For full text: http://lmpg.govt.nz/opapers.htm#OP002. PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; *Adult Literacy; Basic Skills; Case Studies; Competency Based Education; Developed Nations; *Educational Benefits; Educational Change; Educational History; Foreign Countries; *Learning Motivation; *Literacy Education; National Programs; Program Implementation; Reading Skills; *Workplace Literacy IDENTIFIERS *New Zealand ABSTRACT This report summarizes issues facing New Zealand's modern adult literacy movement and places it in the context of the rapidly changing skill demands of the 21st century. Part I introduces political, economic, and social issues facing New Zealand. Chapter 1 provides an overview of the issues and structures that create the current climate. Part II provides a history of adult literacy in New Zealand. Chapter 2 defines literacy for the 21st century; identifies how literate New Zealanders are, and considers literacy needs by industry. Chapter 3 provides a brief history of New Zealand's literacy movement, describes emergence of workplace literacy, and discusses theoretical underpinnings Freirean and competency-based models. -

Moment of Rupture

Moments of Rupture Changing the State Project for Teachers: A Regulation Approach Study in Education Industrial Relations by Patricia Gay Simpkin A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Industrial Relations Victoria University of Wellington 2002 CONTENTS Contents Page Abstract v Acknowledgements vi Abbreviations vii List of Figures viii Chapter 1 Introduction The Context 1 The Thesis 3 The Case Study 4 The Analytical Framework 7 Including Ideological Influences 9 The Structure 10 References 13 Chapter 2 Regulation Theory Introduction 14 Regulation Theory 19 Concepts 21 The Regulation Approach to the State 25 Connecting the Regulation Approach and Education Policy 27 Connecting the State and Education 31 The Relative Autonomy of the Classroom 34 Conclusion 36 Chapter 3 Connecting the Research Problem, the Case Study, and Regulation Theory – Methodological Considerations Introduction 39 Defining the Research Problem in Terms of the Regulation Approach 39 Introducing the Case Study 41 Factors Affecting the Case Study 44 Industrial Relations as a Heuristic Device 45 The Researcher as Participant 48 Specifics of the Research 53 Conclusion 56 Chapter 4 The Discourse of the PPTA – The Keynesian Welfare National State Educational Settlement The Education Settlement of the KWNS 58 The Ideology of the KWNS Education Settlement 59 Theory and Educational Research within the KWNS 62 The KWNS Education Partnership 67 Discontinuities with the Discourse 69 -

Parliamentary Service 2 Annual Report 2016 - 2017

A. 13 1 Annual Report 2016 - 2017 Parliamentary Service 2 Annual Report 2016 - 2017 Presented to the House of Representatives pursuant to section 44(1) of the Public Finance Act 1989 ISSN 2324-2868 (Print) ISSN 2324-2876 (Online) Copyright Except for images with existing copyright and the Parliamentary Service logo, this copyright work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- Non-commercial-Share Alike 3.0 New Zealand licence. You are free to copy, distribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes as long as you attribute the work to the Parliamentary Service and abide by the other licence terms. Note: the use of any Parliamentary logo [by any person or organisation outside of the New Zealand Parliament] is contrary to law. To view a copy of this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licences/ by-nc-sa/3.0/nz 3 Contents 5 Foreword: Speaker of the House of Representatives 6 Delivering a better service 9 About Us 13 Highlights from 2016/17 15 Our achievements this year 19 Supporting our people to support members 25 Measuring our performance 32 Statement of responsibility 33 Independent Auditor’s Report 37 Financial Statements for the year ended 30 June 2017 4 Annual Report 2016 - 2017 5 Foreword: Speaker of the House of Representatives The Parliamentary Service (the Service) supports the institution of Parliament by providing administrative and support services to the House of Representatives and its members of Parliament. It has been another fulfilling and productive year for the Significant work continues Service, as it continues to enhance its ability to better to create a Parliament that support members of Parliament and make Parliament itself is safe and accessible to all.