Kootenai River After Imposing the Slot Limit Regulation and Spawning Closure from Libby Dam to Fisher River in 1994

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Guide to Rural Living in Northwest Montana

A guide to rural living in northwest Montana Lincoln Conservation District PO Box 2170 949 US Highway 93 North Eureka, Montana 59917-2170 Phone (406) 297-2233 • Fax (406) 296-7188 www.lincolncd.org Provided by: [email protected] Lincoln Conservation District Lincoln County Area Map British Columbia West Northwest Kootenai Ten Peak Lakes )"92 !( !( Eureka Rexford Tob Scenic Scenic ac c o R Area Area ive Yaak r £93 # Koocanusa Bridge [ )"508 # D i c k e y Fortine L a k e # # Sylvanite Trego # Stryker - W < Y ¬37 -- a « Bo )"567 L h n a n i e t rs k a Fer e r R y k f - i v i e s e h r - K - > o o c [£2 a n u )"36 n s te a Koo ai River Troy !( Idaho Libby Dam !( C Libby a F i b s i h n e r e F R 56 t i «¬ s M i h v e e r B u l l o r R L a k e u i Ross n v e t r Creek a R i o - n a Cedars M s d T H W w [£2 i y l 2 d 0 e 0 r - n - > e s #Happy's Inn s T h o m p s o n alispell--> I L a k e s -K Legend # Unincorporated Towns !( Incorporated Towns Rivers/Streams Highways/Roads 5 0 5 10 15 20 Miles Lincoln County Introduction Welcome to Lincoln County . 3 Rural Living Handbook Lincoln County Facts . -

Libby, Montana

NORTHWEST GEOLOGY The Journal of The Tobacco Root Geological Society Volume 35, 2006 31st Annual Field Conference Libby, Montana August 3-6, 2006 Published by The Tobacco Root Geological Society, Inc. P.O. Box 2734 Missoula, Montana 59806 http://trgs.org Edited by: Richard I. Gibson and Robert C. Thomas Cover: Miners, Snowshoe Gulch, 1897. From Mrs. Sam Ratekin and Spokane Statesman-Review, 1959. Above: Cross section based on gravity modeling. From M.D. Kleinkopf, Geophysical Interpretations of the Libby Thrust Belt, U.S.G.S. Prof. Paper 1546, 1997. The Tobacco Root Geological Society, Inc. P.O. Box 2734 Missoula, Montana 59806 Officers, 2006: President: Larry Smith, Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, Butte Vice-President: James Sears, Dept. of Geology, Univ. of Montana, Missoula Secretary-Treasurer: George Furniss, MT Dept. of Environmental Quality, Helena Corresponding Secretary: Emily Geraghty, Dept. of Geology, Univ. of Montana, Missoula Webmaster: Dick Gibson Board of Directors, 2006: Richard B. Berg, Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, Butte, MT Bruce E. Cox, Stillwater Mining Co., Nye, MT Marie Marshall Garsjo, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Ft. Worth, TX Richard I. Gibson, Gibson Consulting, Butte, MT Larry Johnson, Consultant, Missoula, MT Robert C. Thomas, Dept. of Environmental Sciences, U. of Montana-Western, Dillon, MT Conference Organizers, Libby Field Conference: Bruce E. Cox, Stillwater Mining Co., Nye, MT Marie Marshall Garsjo, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Ft. Worth, TX Ann Marie Gooden, Libby, MT ISSN: 0096-7769 © 2006 The Tobacco Root Geological Society, Inc. http://trgs.org ii NORTHWEST GEOLOGY The Journal of The Tobacco Root Geological Society Volume 35, 2006 Libby Field Conference Table of Contents Author Page Title Montana DEQ 1 Libby District Historical Mine Narrative Art Montana 11 The Rainy Creek alkaline ultramafic igneous complex near Libby, MT Montana DEQ 17 Rainy Creek Historical Mine Narrative Derek L. -

Effects of Fishing on Long-Lived Marine Organisms

Effects of Fishing on 13 Long-Lived Marine Organisms Selina S. Heppell, Scott A. Heppell, Andrew J. Read, and Larry B. Crowder North America once had a rich array of megafauna sidered in jeopardy by Norse (1993) are overexploited, that included 31 genera of large and long-lived mam- and a substantial number of currently threatened or mals such as mastodons, horses, and saber-toothed endangered marine animals are subject to direct ex- tigers. But around 12,000 years ago, these organisms ploitation or bycatch (Crowder and Murawski 1998). disappeared. What led to the demise of this fascinat- One characteristic of many extinct or endangered ing fauna? Although it is still the subject of some de- marine animals is that they are relatively large, long- bate, a prevailing hypothesis is that these organisms lived organisms. Hunters in the sea often focused first were rendered extinct as technology invaded the con- on large organisms and hunted them intensively. tinent and moved from west to east (Frison 1998; Mar- Steller’s sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas), a massive siren- tin 1973), either carried directly by humans as they ian first discovered by Europeans in 1741, reached spread through the continent or as the technology lengths exceeding 8 m and weights of over 5 tons. passed through existing populations. Even with mod- Abundant, slow moving, and unafraid of humans, est technologies, hunters were able to hunt or modify Steller’s sea cows were hunted intensively for their the habitats of these large organisms to force their ex- meat and driven to extinction by 1768. -

FEBRUARY 1, 2018 10 11 VOTING MEMBERS 12 Kevin Anson (Designee for Scott Bannon)

1 GULF OF MEXICO FISHERY MANAGEMENT COUNCIL 2 3 268TH MEETING 4 5 FULL COUNCIL SESSION 6 7 Hyatt Centric New Orleans, Louisiana 8 9 JANUARY 29-FEBRUARY 1, 2018 10 11 VOTING MEMBERS 12 Kevin Anson (designee for Scott Bannon)...................Alabama 13 Patrick Banks...........................................Louisiana 14 Leann Bosarge.........................................Mississippi 15 Doug Boyd...................................................Texas 16 Roy Crabtree.................................................NMFS 17 Dale Diaz.............................................Mississippi 18 Phil Dyskow...............................................Florida 19 Tom Frazer................................................Florida 20 Johnny Greene.............................................Alabama 21 Martha Guyas (designee for Jessica McCawley)..............Florida 22 Campo Matens............................................Louisiana 23 Paul Mickle (designee for Joe Spraggins)..............Mississippi 24 Robin Riechers..............................................Texas 25 John Sanchez..............................................Florida 26 Bob Shipp.................................................Alabama 27 Greg Stunz..................................................Texas 28 Ed Swindell.............................................Louisiana 29 30 NON-VOTING MEMBERS 31 Glenn Constant..............................................USFWS 32 Dave Donaldson..............................................GSMFC 33 LT Mark Zanowicz.............................................USCG -

2021 Louisiana Recreational Fishing Regulations

2021 LOUISIANA RECREATIONAL FISHING REGULATIONS www.wlf.louisiana.gov 1 Get a GEICO quote for your boat and, in just 15 minutes, you’ll know how much you could be saving. If you like what you hear, you can buy your policy right on the spot. Then let us do the rest while you enjoy your free time with peace of mind. geico.com/boat | 1-800-865-4846 Some discounts, coverages, payment plans, and features are not available in all states, in all GEICO companies, or in all situations. Boat and PWC coverages are underwritten by GEICO Marine Insurance Company. In the state of CA, program provided through Boat Association Insurance Services, license #0H87086. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, DC 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. © 2020 GEICO CONTENTS 6. LICENSING 9. DEFINITIONS DON’T 11. GENERAL FISHING INFORMATION General Regulations.............................................11 Saltwater/Freshwater Line...................................12 LITTER 13. FRESHWATER FISHING SPORTSMEN ARE REMINDED TO: General Information.............................................13 • Clean out truck beds and refrain from throwing Freshwater State Creel & Size Limits....................16 cigarette butts or other trash out of the car or watercraft. 18. SALTWATER FISHING • Carry a trash bag in your car or boat. General Information.............................................18 • Securely cover trash containers to prevent Saltwater State Creel & Size Limits.......................21 animals from spreading litter. 26. OTHER RECREATIONAL ACTIVITIES Call the state’s “Litterbug Hotline” to report any Recreational Shrimping........................................26 potential littering violations including dumpsites Recreational Oystering.........................................27 and littering in public. Those convicted of littering Recreational Crabbing..........................................28 Recreational Crawfishing......................................29 face hefty fines and litter abatement work. -

MAN CCRC..Ani~::,,"'

,,"!>< MANCCRC..ANi~::,,"',,- ~ ~ r Zjfi>~ ~ 92 DEFINING FISHERIES A User's Glossary Kenneth J. Roberts Jerald W. Horst John E. Roussel JosephA. Shephard LOUISIANA SEA GRANT COLLFGF. ['ROGRAM Louisiana State Vniversity INTRODUCTION Theharvest of fish by commercialand recreationaltishermen is regulatedby federal LOUISIANA andstate agencies that develop plans by which SEA GRANT to managefishery resources.In so doing, College Program agenciesseek advice from fishermen and others involvedwith the fishing industry, Manage- ment plans include technical words and terms thatare difficult to understand,This glossary ~ LauISIAeA givesdefinitions that should help fishermen COOPERATIVE EXTENSION SERVICE understandthe scientific basis of management. EOIIISIENESTREE UNIVERSITT EGRIClj'LTUREI CENTER Thus, their comments and advice will be more usefulin planningand management. Kenneth J. Roberts, Putting fishery managementterms in Marine ResourceEconomics Specialist Louisiana Cooperative Extension Service nonscientificwords may makesome definitions Louisiana State University toosimple, but theauthors sought to getthe main idea acrosson each term. Some terms are Jerald W. Horst, Area Agent Fisheries! referredto by scientistsas letters or groupsof Louisiana Cooperative Extension Service letters acronymsland theseare listed at the end Louisiana StateUniversity of the publicationfor quick reference.The word fish is usedthroughout, and includesfinfish and John E, Roussel, Marine Fisheries Division shellfishspecies, A mail-inform is providedto Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries identify words and terms that need to be includedin a futureprinting. JosephA, Shephard, FisheriesResearch Division Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Amberjack on front cover courtesy of Dr. Bruce A Thompson, LSU Coastal Fisheries Institute The researchthat resulted in this publication was A Seeanrll<al mortality. supported by the Louisiana SeaGrant College ABC Seeallourable biologicai catch. Program of Louisiana State University. -

Chapter 220-3 Marine Resources Division

Conservation and Natural Resources Chapter 220-3 ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND NATURAL RESOURCES ADMINISTRATIVE CODE CHAPTER 220-3 MARINE RESOURCES DIVISION TABLE OF CONTENTS 220-3-.01 Shrimping 220-3-.02 Oystering 220-3-.03 Use Of Nets And Harvest Of Mullet 220-3-.04 Miscellaneous And Public Access Regulation 220-3-.05ER Harvesting Limit For Oysters (Emergency Rule Expired) 220-3-.06.02ER Discarding Dead Fish And Other Seafoods Into The Gulf Of Mexico 220-3-.07.03ER Closed Shrimping In The Waters Of The Gulf Of Mexico (Emergency Rule Expired) 220-3-.08 Redfish And Speckled Sea Trout Regulations (Repealed 8/10/15) 220-3-.09.07ER Closed Fishing Of Any Speckled Trout (Emergency Rule - Repealed) 220-3-.10ER Discarding Of Dead Fish And Other Dead Seafoods Into The Gulf Of Mexico (Emergency Rule - Expired) 220-3-.11 Red Drum (Redfish) And Spotted Sea Trout Regulations (Repealed 8/10/15) 220-3-.12 Red Drum And Spotted Sea Trout Game Fish Regulation 220-3-.13 (Reserved) 220-3-.14 (Reserved) 220-3-.15 Oyster Season And Harvest Limits 220-3-.16 (Reserved) 220-3-.17ER Prohibition Of Nets - Gulf Of Mexico (Emergency Rule Expired) 220-3-.18 (Reserved) 220-3-.19 (Reserved) 220-3-.20 Prohibition Of Commercial Taking Or Possession, Or Purchase/Sale/Trade Of King Mackerel (Repealed 6/19/18) 220-3-.21ER Prohibition Of Commercial Taking, Possession, Or Landing Of Red Snapper (Emergency Rule Effective 4/6/92) Supp. 9/30/21 3-1 Chapter 220-3 Conservation and Natural Resources 220-3-.22 Creel/Possession Limit On Ling (Cobia) (Repealed 4/20/15) 220-3-.23 -

ASMFC Stock Status Overview

American Eel ASMFC Stock Status Overview American Lobster Atlantic Cobia This document provides an overview of stock status for the Commission’s 27 managed species or species groups. Graphs contain the most recent information available and have been vetted through the relevant species technical committee. Where Atlantic Croaker biomass data is lacking, other fishery indicators are used (i.e., landings, fishing mortality rates). Time frames differ based on Atlantic Herring data availability. October 2020 Atlantic Menhaden Atlantic Striped Bass Atlantic Sturgeon Black Drum Black Sea Bass Bluefish Coastal Sharks Horseshoe Crab Jonah Crab Northern Shrimp Red Drum Scup Shad & River Herring Spanish Mackerel Spiny Dogfish Spot Spotted Seatrout Summer Flounder Tautog Weakfish Vision: Sustainable and Cooperative Management of Atlantic Coastal Fisheries Winter Flounder Quick Guide to ASMFC Species Stock Status (Current as of October 2020) = Rebuilt/Sustainable / = Recovering/Rebuilding = Depleted ? = Unknown *= Concern STATUS/ REBUILDING STATUS & SPECIES OVERFISHED OVERFISHING TRENDS SCHEDULE 2017 stock assessment update American Eel Depleted Unknown indicates resource remains depleted. GOM/GBK stock abundance Gulf of Maine/ has increased since the 1980s. American Georges Bank Not Depleted N 2020 benchmark assessment to Lobster (GOM/GBK) be presented to the Board in October. SNE stock has collapsed and is experiencing recruitment Southern New Depleted N failure. 2020 benchmark England assessment to be presented to the Board in October. Depleted on coastwide basis; Amendment 3 established 2013 moratorium unless river- American Shad Depleted Unknown specific sustainability can be documented; benchmark assessment scheduled for 2020. In 2020, the TLA was updated to incorporate additional fishery-independent surveys, Atlantic age and length information, an Unknown Unknown ? Croaker updated reference period, regional characteristics, and an updated management trigger mechanism. -

Upper Red Lake 04-0035-01 BELTRAMI COUNTY

Upper Red Lake 04-0035-01 BELTRAMI COUNTY Lake Water Quality Summary Upper Red Lake is located to the west of Waskish, MN in Beltrami County. The western half of the basin is located within the Red Lake Reservation. Upper and Lower Red Lake together is the largest inland water body in Minnesota. Upper Red Lake covers 119,274 acres and has a maximum depth of 15 feet (Table 1). Upper Red Lake has 41 inlets and one outlet, which classify it as a drainage lake (Figure 1). Water exits Upper Red Lake to Lower Red Lake and enters the Red Lake River, which flows west to the Red River. Water quality data have been collected on Upper Red Lake since 1990 (Tables 2-3). These data show that the lake is eutrophic (59), which is characteristic of dense aquatic plant growth and algae blooms in late summer. The Upper Red Lake walleye fishery is one of the most valuable resources to the local and state economy of all the lakes in Minnesota. Upper Red Lake is monitored extensively by the Red Lake Department of Natural Resources. This long-term data set is beneficial in future planning for this economically and ecologically valuable water resource. The Upper Red Lake Area Association is active in outreach, tourism promotion, and area events. Its mission is “To promote and enhance the Upper Red Lake Area, and the economic, commercial, and social interested of its inhabitants.” Table 1. Location data and physical characteristics for Upper Red Lake. Location Data Physical Characteristics MN Lake ID: 04-0035-01 Surface area (acres): 119,274 County: Beltrami % Littoral area: 100% Ecoregion: Northern Minnesota Wetlands Max depth (ft), (m): 15, 4.6 Major Drainage Basin: Upper/Lower Red Lake Inlets: 41 Latitude/Longitude: 48.131237 / -94.766452 Outlets: 1 Invasive Species: Starry stonewart Public Accesses: 2 Table 2. -

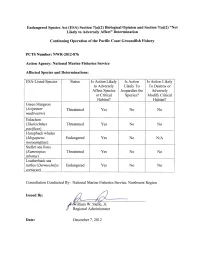

Endangered Species Act (ESA) Section 7(A)(2) Biological Opinion and Section 7(A)(2) "Not Likely to Adversely Affect" Determination

Endangered Species Act (ESA) Section 7(a)(2) Biological Opinion and Section 7(a)(2) "Not Likely to Adversely Affect" Determination Continuing Operation of the Pacific Coast Groundfish Fishery PeTS Number: NWR-2012-876 Action Agency: National Marine Fisheries Service Affected Species and Determinations: ESA-Listed Species Status Is Action Likely Is Action Is Action Likely to Adversely Likely To To Destroy or Affect Species Jeopardize the Adversely or Critical Species? Modify Critical Habitat? Habitat? Green Sturgeon (Acipenser Threatened Yes No No medirostris) Eulachon (Thaleichthys Threatened Yes No No vaci/icus) Humpback whales (Megaptera Endangered Yes No N/A novaeangliae) Steller sea lions (Eumetopias Threatened Yes No No jubatus) Leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys Endangered Yes No No coriacea) Consultation Conducted By: National Marine Fisheries Service, Northwest Region Issued By: illiam W. Stelle, Jr. Regional Administrator Date: December 7,2012 List of Acronyms ACL Annual Catch Limits AKR Alaska Region A-SHOP At-Sea Hake Observer Program BRT Biological Review Team BRD Bycatch Reduction Device CA/OR/WA California/Oregon/Washington CDFG California Department of Fish and Game CI Confidence Interval COSEWIC Committee on the Status for Endangered Wildlife in Canada CPFVs Commercial Passenger Fishing Vessels CPUE Catch Per Unit Effort DPS Distinct Population Segment DQA Data Quality Act DU Designatable Unit EEZ Exclusive Economic Zone EFH Essential Fishing Habitat EFPs Exempt Fishing Permits ESA Endangered Species Act ESU Evolutionarily -

Sediment Characteristics and Transport in the Kootenai River White Sturgeon Critical Habitat Near Bonners Ferry, Idaho

Prepared in cooperation with the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho Sediment Characteristics and Transport in the Kootenai River White Sturgeon Critical Habitat near Bonners Ferry, Idaho Scientific Investigations Report 2009–5228 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Kootenai River below Moyie River at river kilometer 257.41 looking upstream towards the left bank. (Photograph taken by Robert J. Kasun, Wildland Hydrology, May 2008) Sediment Characteristics and Transport in the Kootenai River White Sturgeon Critical Habitat near Bonners Ferry, Idaho By Ryan L. Fosness and Marshall L. Williams Prepared in cooperation with the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho Scientific Investigations Report 2009–5228 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2009 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Fosness, R.L., and Williams, M.L., 2009, Sediment characteristics and transport in the Kootenai River white sturgeon critical habitat near Bonners Ferry, Idaho: U.S. -

Cabinet-Yaak Grizzly Bear Recovery 2016 Research and Monitoring Progress Report

CABINET-YAAK GRIZZLY BEAR RECOVERY AREA 2016 RESEARCH AND MONITORING PROGRESS REPORT PREPARED BY WAYNE F. KASWORM, THOMAS G. RADANDT, JUSTIN E. TEISBERG, ALEX WELANDER, MICHAEL PROCTOR, AND HILARY COOLEY 2017 UNITED STATES FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE GRIZZLY BEAR RECOVERY COORDINATOR'S OFFICE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA, MAIN HALL ROOM 309 MISSOULA, MONTANA 59812 (406) 243-4903 1 This annual report is cumulative and represents data collected since the inception of this monitoring program in 1983. New information collected or made available to this study is incorporated, reanalyzed, and summarized annually. Information in this report supersedes previous reports. Please obtain permission prior to citation. Cite this report as follows: Kasworm, W. F., T. G. Radandt, J.E. Teisberg, A. Welander, M. Proctor, and H. Cooley. 2017. Cabinet-Yaak grizzly bear recovery area 2016 research and monitoring progress report. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Missoula, Montana. 101 pp. ABSTRACT Sixteen grizzly bears were monitored with radio collars during portions of 2016. Research monitoring included seven females (three adults and four subadults) and nine males (five adults and four subadults) in the Cabinet-Yaak ecosystem (CYE). Two bears of these bears were from the Cabinet Mountains (1 subadult male and 1 subadult female) and part of the augmentation program. Grizzly bear monitoring and research has been ongoing in the Cabinet Mountains since 1988 and in the Yaak River since 1986. Sixty-eight resident bears have been captured and monitored through telemetry in the two areas from 1986-2016. Research in the Cabinet Mountains indicated that only a small population remained as of 1988.