Electronic Transcriptions of New Testament Manuscripts and Their Accuracy, Documentation and Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And the Goal of New Testament Textual Criticism

RECONSTRUCTING THE TEXT OF THE CHURCH: THE “CANONICAL TEXT” AND THE GOAL OF NEW TESTAMENT TEXTUAL CRITICISM by DAVID RICHARD HERBISON A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Master of Arts in Biblical Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard ............................................................................... Dr. Kent Clarke, Ph.D.; Thesis Supervisor ................................................................................ Dr. Craig Allert, Ph.D.; Second Reader TRINITY WESTERN UNIVERSITY December 2015 © David Richard Herbison ABSTRACT Over the last several decades, a number of scholars have raised questions about the feasibility of achieving New Testament textual criticism’s traditional goal of establishing the “original text” of the New Testament documents. In light of these questions, several alternative goals have been proposed. Among these is a proposal that was made by Brevard Childs, arguing that text critics should go about reconstructing the “canonical text” of the New Testament rather than the “original text.” However, concepts of “canon” have generally been limited to discussions of which books were included or excluded from a list of authoritative writings, not necessarily the specific textual readings within those writings. Therefore, any proposal that seeks to apply notions of “canon” to the goals and methods of textual criticism warrants further investigation. This thesis evaluates Childs’ -

University of Birmingham Electronic Transcriptions of New Testament

University of Birmingham Electronic transcriptions of new testament manuscripts and their accuracy, documentation and publication Houghton, H.A.G. DOI: 10.1163/9789004399297_009 License: Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial (CC BY-NC) Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (Harvard): Houghton, HAG 2019, Electronic transcriptions of new testament manuscripts and their accuracy, documentation and publication. in C Clivaz, D Hamidovi & S Savant (eds), Ancient Manuscripts in Digital Culture: Visualisation, Data Mining, Communication . vol. 3, Digital Biblical Studies, vol. 3, Brill, Leiden, pp. 133- 153. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004399297_009 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility: 30/05/2019 Houghton, H..G. (2019). "Electronic Transcriptions of New Testament Manuscripts and their Accuracy, Documentation and Publication". In Ancient Manuscripts in Digital Culture. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004399297_009 https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/9789004399297/BP000008.xml General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. -

Miracle and Mission. the Authentication of Missionaries and Their Message in the Longer Ending of Mark

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament • 2. Reihe Herausgegeben von Martin Hengel und Otfried Hofius 112 ARTI BUS James A. Kelhoffer Miracle and Mission The Authentication of Missionaries and Their Message in the Longer Ending of Mark Mohr Siebeck JAMES A. KELHOFFER, born 1970; 1991 B.A. Wheaton College (IL); 1992 M.A. Wheaton Grad- uate School (IL); 1996 M.A. University of Chicago; 1999 Ph.D. University of Chicago; 1999- 2000 Visiting Assistant Professor of New Testament at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago. Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Kelhoffer, James A.: Miracle and mission : the authentication of missionaries and their message in the longer ending of Mark / James A. Kelhoffer. - Tübingen : Mohr Siebeck, 2000 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament: Reihe 2 ; 112) ISBN 3-16-147243-8 © 2000 by J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), P.O. Box 2040, D-72010 Tübingen. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. The applies particularly to repro- ductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed by Guide-Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper from Papierfabrik Nie- fern and bound by Heinr. Koch in Tübingen. Printed in Germany. ISSN 0340-9570 To my grandparents: Elsie Krath Alberich Anthony Henry Alberich Lillian Jay Kelhoffer f Herbert Frank Kelhoffer, Sr. Magnum opus et adruum, sed Deus adiutor noster est. (Augustine, de civ. D. Preface) Acknowledgments This book is a revision of my doctoral dissertation, "The Authentication of Missionaries and their Message in the Longer Ending of Mark (Mark 16:9-20)," written under the supervision of Adela Yarbro Collins at the University of Chicago and defended on December 9,1998. -

A Textual Commentary on the Greek Received Text of the New Testament, Volume 2 (Matthew 15-20), 2009

i A TEXTUAL COMMENTARY ON THE GREEK RECEIVED TEXT OF THE NEW TESTAMENT Being the Greek Text used in the AUTHORIZED VERSION also known as the KING JAMES VERSION also known as the AUTHORIZED (KING JAMES) VERSION also known as the KING JAMES BIBLE also known as the SAINT JAMES VERSION by Gavin Basil McGrath B.A., LL.B. (Sydney University), Dip. Ed. (University of Western Sydney), Dip. Bib. Studies (Moore Theological College). Formerly of St. Paul’s College, Sydney University. Textual Commentary, Volume: 2 St. Matthew’s Gospel Chapters 15-20. Verbum Domini Manet in Aeternum “The Word of the Lord Endureth Forever” (I Peter 1:25). ii McGrath, Gavin (Gavin Basil), b. 1960. A Textual Commentary on the Greek Received Text of the New Testament, Volume 2 (Matthew 15-20), 2009. Available on the internet http://www.gavinmcgrathbooks.com . Published & Printed in Sydney, New South Wales. Copyright © 2009 by Gavin Basil McGrath. P.O. Box 834, Nowra, N.S.W., 2541, Australia. Dedication Sermon, preached at Mangrove Mountain Union Church, Mangrove Mountain, N.S.W., 2250, Australia, on Thursday 5 November, 2009. Oral recorded form presently available at http://www.sermonaudio.com/kingjamesbible . This copy of Volume 2 (Matt. 15-20) incorporates corrigenda changes from Appendix 6 of the Revised Volume 1 (Matt. 1-14) © 2010 by Gavin Basil McGrath, Appendix 6 of Volume 3 (Matt. 21-25) © 2011 by Gavin Basil McGrath; Appendix 6 of Volume 4 (Matt. 26-28) © 2012 by Gavin Basil McGrath; Appendix 6 of Volume 5 (Mark 1-3) © 2015 by Gavin Basil McGrath; and Appendix 6 of Volume 6 (Mark 4 & 5) © 2016 by Gavin Basil McGrath. -

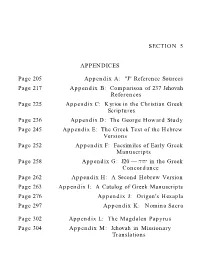

Reference Sources Page 217 Appendix B

SECTION 5 APPENDICES Page 205 Appendix A: "J" Reference Sources Page 217 Appendix B: Comparison of 237 Jehovah References Page 225 Appendix C: Kyrios in the Christian Greek Scriptures Page 236 Appendix D: The George Howard Study Page 245 Appendix E: The Greek Text of the Hebrew Versions Page 252 Appendix F: Facsimiles of Early Greek Manuscripts Page 258 Appendix G: J20 — hwhy in the Greek Concordance Page 262 Appendix H: A Second Hebrew Version Page 263 Appendix I: A Catalog of Greek Manuscripts Page 276 Appendix J: Origen's Hexapla Page 297 Appendix K: Nomina Sacra Page 302 Appendix L: The Magdalen Papyrus Page 304 Appendix M: Jehovah in Missionary Translations Page 306 Appendix N: Correspondence with the Society Page 313 Appendix O: A Reply to Greg Stafford Page 317 ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Page 327 GLOSSARY Page 333 SCRIPTURE INDEX Page 336 SUBJECT INDEX Appendix A: "J" Reference Sources ••205•• The New World Translation replaces the Greek word Kyrios (and occasionally Theos) with the divine name Jehovah 237 times in the Christian Greek Scriptures. (Infrequently, Jehovah appears multiple times in a single verse.) In each of these 237 instances, the Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society has published documentation supporting the translators' selection of Jehovah. Anyone wishing to investigate the use of the Tetragrammaton in the Christian Greek Scriptures will want to consult firsthand the two information sources summarized in this appendix. 1. The Kingdom Interlinear Translation of the Greek Scriptures, copyrighted in 1969 and 1985 by the Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society, is a valuable and primary source of information. -

THE LATIN NEW TESTAMENT OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi THE LATIN NEW TESTAMENT OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi The Latin New Testament A Guide to its Early History, Texts, and Manuscripts H.A.G. HOUGHTON 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 14/2/2017, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © H.A.G. Houghton 2016 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2016 Impression: 1 Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. This is an open access publication, available online and unless otherwise stated distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution –Non Commercial –No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2015946703 ISBN 978–0–19–874473–3 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, Vol. I. by Frederick Henry Ambrose Scrivener

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, Vol. I. by Frederick Henry Ambrose Scrivener This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, Vol. I. Author: Frederick Henry Ambrose Scrivener Release Date: June 28, 2011 [Ebook 36548] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A PLAIN INTRODUCTION TO THE CRITICISM OF THE NEW TESTAMENT, VOL. I.*** A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament For the Use of Biblical Students By The Late Frederick Henry Ambrose Scrivener M.A., D.C.L., LL.D. Prebendary of Exeter, Vicar of Hendon Fourth Edition, Edited by The Rev. Edward Miller, M.A. Formerly Fellow and Tutor of New College, Oxford Vol. I. George Bell & Sons, York Street, Covent Garden Londo, New York, and Cambridge 1894 Contents Preface To Fourth Edition. .5 Description Of The Contents Of The Lithographed Plates. .9 Addenda Et Corrigenda. 30 Chapter I. Preliminary Considerations. 31 Chapter II. General Character Of The Greek Manuscripts Of The New Testament. 54 Chapter III. Divisions Of The Text, And Other Particulars. 98 Appendix To Chapter III. Synaxarion And Eclogadion Of The Gospels And Apostolic Writings Daily Throughout The Year. 127 Chapter IV. The Larger Uncial Manuscripts Of The Greek Testament. -

Rethinking the Western Non-Interpolations: a Case for Luke Re-Editing His Gospel

Rethinking the Western Non-interpolations: A Case For Luke Re-editing His Gospel by Giuseppe Capuana BA (Mus), GradDipEd, BTheol (Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy University of Divinity 2018 Abstract This thesis presents a new paradigm for understanding the Western non-interpolations. It argues that when Luke originally wrote his Gospel it did not contain 22:19b–20; 24:3b, 6a, 12, 36b, 40, 51b and 52a. However, at a later time, around the time Luke wrote Acts, he returned to his Gospel creating a second edition which contained these readings. My thesis makes the case that the paradigm of scribal interpolation is problematic. Working under this paradigm the results of external and internal evidence appear conflicting and scholars are generally forced to give greater preference to one set of evidence over the other. However, a balanced weighting of the external and internal evidence points us towards the notion that Luke was responsible for both the absence and the inclusion of 22:19b–20; 24:3b, 6a, 12, 36b, 40, 51b and 52a. Chapter one introduces the Western non-interpolations. It also makes the case that the quest for the original text of Luke’s Gospel should not be abandoned. Chapter two is on the history, theory and methodology of the Western non-interpolations. It begins with an overview of the text-critical scholarship emerging during the nineteenth century, particularly the influence of Brooke Foss Westcott and Fenton John Anthony Hort. It also covers the period after Westcott and Hort to the present. -

The Text of the New Testament 2Nd Edit

THE TEXT OF THE NEW TESTAMENT Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration BY BRUCE M. METZGER Professor of Mew Testament Language and Literature Princeton Theological Seminary SECOND EDITION OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS Preface to the Second Edition During the four years that have elapsed since the initial publication of this book in 1964, a great amount of textual research has continued to come from the presses in both Europe and America. References to some of these publications were included in the German translation of the volume issued in 1966 under the title Der Text des Neuen Test- aments; Einftihrung in die neutestamentliche Textkritik (Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart) . The second printing of the English edition provides opportunity to introduce a variety of small alterations throughout the volume as well as to include references to more than one hundred and fifty books and articles dealing with Greek manuscripts, early versions, and textual studies of recently discovered witnesses to the text of the New Testament. In order not to disturb the pagination, most of the new material has been placed at the close of the book (pp. 261-73), to which the reader's attention is directed by appropriate cross references. BRUCE M. METZGER February ig68 Preface The necessity of applying textual criticism to the books of the New Testament arises from two circumstances : (a) none of the original documents is extant, and (b) the existing copies differ from one another. The textual critic seeks to ascer- tain from the divergent copies which form of the text should be regarded as most nearly conforming to the original. -

The So-Called Mixed Text: an Examination of the Non-Alexandrian and Non-Byzantine Text-Type in the Catholic Epistles

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2007 The So-Called Mixed Text: an Examination of the Non-Alexandrian and Non-Byzantine Text-Type in the Catholic Epistles Clinton S. Baldwin Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Catholic Studies Commons Recommended Citation Baldwin, Clinton S., "The So-Called Mixed Text: an Examination of the Non-Alexandrian and Non-Byzantine Text-Type in the Catholic Epistles" (2007). Dissertations. 14. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/14 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE SO-CALLED MIXED TEXT: AN EXAMINATION OF THE NON-ALEXANDRIAN AND NON-BYZANTINE TEXT-TYPE IN THE CATHOLIC EPISTLES by Clinton Baldwin Co-Advisers: William Warren Robert Johnston Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE SO-CALLED MIXED TEXT: AN EXAMINATION OF THE NON- ALEXANDRIAN AND NON-BYZANTINE TEXT-TYPE IN THE CATHOLIC EPISTLES Name of researcher: Clinton Baldwin Name and degree of faculty co-advisers: William Warren, Ph.D. -

247 Matt. 18:2 “Jesus” (TR & AV) {A} Preliminary Textual Discussion. The

247 Matt. 18:2 “Jesus” (TR & AV) {A} Preliminary Textual Discussion. The First Matter. Tischendorf considers that without qualification the variant is followed by F 09 (9th century). By contrast, Swanson considers that the original Byzantine manuscript F 09 was blank at this verse, and that a later “corrector” added in its present verse 2 (I assume sometime before the end of the 16th century). I am unable to inspect this manuscript myself. But either way, the variant is a minority Byzantine reading, since it was either originally part of F 09, or was subsequently written out as the variant by a Byzantine scribe. Moreover nothing much hangs on this, since one can show the reading inside the closed class of sources from elsewhere. The Second Matter (Diatessaron formatting). Inside the closed class of sources, the Vulgate reads Latin, “ Iesus (Jesus),” at both Matt. 18:2 and Luke 9:47. As a consequence of Diatessaron formatting, it is not possible to tell if the prima facie reading of Matt. 18:2 in the Latin Vulgate Codex of the Sangallensis Diatessaron, got its Latin, “Ihesus (Jesus),” from one or both of these sources. Thus no reference is made to this Diatessaron, infra . Likewise, outside the closed class of sources, due to Diatessaron formatting, it is not possible to tell where the prima facie reading of Luke 9:47 in Ciasca’s Latin-Arabic Diatessaron got the Latin, “ Iesus ,” from. Thus once again, no reference is made to this Diatessaron, infra . Principal Textual Discussion. At Matt. 18:2, the TR’s Greek, “ o (-) Iesous (Jesus),” in the words, “And Jesus called” etc. -

The Lord Has Preserved His Word

The doctrine of Holy Scripture, its providential preservation and its faithful translation The Lord has preserved His Word: The doctrine of Holy Scripture, its providential preservation and its faithful translation Dr J. Cammenga Editorial Consultant of the Trinitarian Bible Society 1 The Lord has preserved His Word cover image: beginning of the Gospel according to Mark in Codex Boreelianus The Lord has preserved His Word: The doctrine of Holy Scripture, its providential preservation and its faithful translation This article has been approved for publication by the General Committee of the Trinitarian Bible Society. The author, who has been given liberty to use his own style and methodology in the presentation of the subject, is one of the Society’s Editorial Consultants and a schoolmaster. Dr Cammenga is resident in The Netherlands. ©2014 Trinitarian Bible Society Tyndale House, Dorset Road London SW19 3NN UK 2 The doctrine of Holy Scripture, its providential preservation and its faithful translation The Lord has preserved His Word: The doctrine of Holy Scripture, its providential preservation and its faithful translation 1. Introduction: What difference does belief in Providential preservation make? ........................................................... 4 2. One Bible or many? The message and the words ................................................................................................................. 4 Different versions; Different theories of translation; Different underlying texts; A message and the words expressing it; Preservation of the Scripture message and the words expressing it; The preservation of Scripture rejected by modern critics; The text of Scripture only 130 years old? The Critical Text rejected by the Reformers; The Critical Text view has resulted in revised Bible texts and Bible versions; A major reason for undertaking this study.