Rethinking the Western Non-Interpolations: a Case for Luke Re-Editing His Gospel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Empty Tomb

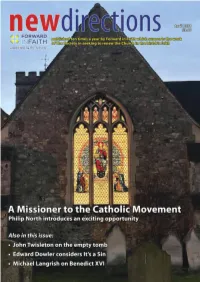

content regulars Vol 24 No 299 April 2021 6 gHOSTLy cOunSEL 3 LEAD STORy 20 views, reviews & previews AnDy HAWES A Missioner to the catholic on the importance of the church Movement BOOkS: Christopher Smith on Philip North introduces this Wagner 14 LOST SuffOLk cHuRcHES Jack Allen on Disability in important role Medieval Christianity EDITORIAL 18 Benji Tyler on Being Yourself BISHOPS Of THE SOcIETy 35 4 We need to talk about Andy Hawes on Chroni - safeguarding cles from a Monastery A P RIEST 17 APRIL DIARy raises some important issues 27 In it from the start urifer emerges 5 The Empty Tomb ALAn THuRLOW in March’s New Directions 19 THE WAy WE LIvE nOW JOHn TWISLETOn cHRISTOPHER SMITH considers the Resurrection 29 An earthly story reflects on story and faith 7 The Journal of Record DEnIS DESERT explores the parable 25 BOOk Of THE MOnTH WILLIAM DAvAgE MIcHAEL LAngRISH writes for New Directions 29 Psachal Joy, Reveal Today on Benedict XVI An Easter Hymn 8 It’s a Sin 33 fAITH Of OuR fATHERS EDWARD DOWLER 30 Poor fred…Really? ARTHuR MIDDLETOn reviews the important series Ann gEORgE on Dogma, Devotion and Life travels with her brother 9 from the Archives 34 TOucHIng PLAcE We look back over 300 editions of 31 England’s Saint Holy Trinity, Bosbury Herefordshire New Directions JOHn gAyfORD 12 Learning to Ride Bicycles at champions Edward the Confessor Pusey House 35 The fulham Holy Week JAck nIcHOLSOn festival writes from Oxford 20 Still no exhibitions OWEn HIggS looks at mission E R The East End of St Mary's E G V Willesden (Photo by Fr A O Christopher Phillips SSC) M I C Easter Chicks knitted by the outreach team at Articles are published in New Directions because they are thought likely to be of interest to St Saviour's Eastbourne, they will be distributed to readers. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The priesthood of Christ in Anglican doctrine and devotion: 1827 - 1900 Hancock, Christopher David How to cite: Hancock, Christopher David (1984) The priesthood of Christ in Anglican doctrine and devotion: 1827 - 1900, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7473/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 VOLUME II 'THE PRIESTHOOD OF CHRIST IN ANGLICAN DOCTRINE AND DEVOTION: 1827 -1900' BY CHRISTOPHER DAVID HANCOCK The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Durham, Department of Theology, 1984 17. JUL. 1985 CONTENTS VOLUME. II NOTES PREFACE 1 INTRODUCTION 4 CHAPTER I 26 CHAPTER II 46 CHAPTER III 63 CHAPTER IV 76 CHAPTER V 91 CHAPTER VI 104 CHAPTER VII 122 CHAPTER VIII 137 ABBREVIATIONS 154 BIBLIOGRAPHY 155 1 NOTES PREFACE 1 Cf. -

University of Birmingham the Garland of Howth (Vetus Latina

University of Birmingham The Garland of Howth (Vetus Latina 28): A Neglected Old Latin witness in Matthew Houghton, H.A.G. License: Other (please specify with Rights Statement) Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (Harvard): Houghton, HAG 2019, The Garland of Howth (Vetus Latina 28): A Neglected Old Latin witness in Matthew. in G Allen (ed.), The Future of New Testament Textual Scholarship From H. C. Hoskier to the Editio Critica Maior and Beyond. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament, vol. 417, Mohr Siebeck, pp. 247-264. Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility: 25/02/2019 Houghton , H. A. G. (2019) The Garland of Howth (Vetus Latina 28): A Neglected Old Latin witness in Matthew. In G. V. Allen (Ed. ), The future of New Testament textual scholarship (pp. 247-264). Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck. For non commercial use only. General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. -

What Difference Does It Make?1 the Greek Text We Accept Makes a Big Difference

WHAT DIFFERENCE DOES IT MAKE?1 THE GREEK TEXT WE ACCEPT MAKES A BIG DIFFERENCE WILBUR N. PICKERING Missionary Valparaiso De Goias, GO, Brazil I. INTRODUCTION It has been commonly argued, for at least 260 years,2 that no doctrine will be affected no matter what Greek text one may use. In my own experience, for over fifty years, when I have raised the question of what is the correct Greek text of the NT, regardless of the audience, the usual response has been: “What difference does it make?” The purpose of this article is to answer that question, at least in part. The eclectic Greek text presently in vogue, N-A26/UBS3 [here- after NU] represents the type of text upon which most modern versions are based.3 The KJV and NKJV follow a rather dif- ferent type of text, a close cousin of the Majority Text.4 The 1 This article is a revision (considerable) of ‘Appendix G’ in my book, The Identity of the New Testament Text II, Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 3rd ed., 2003. (In the online version it is Appendix H.) 2 John Bengel, a textual critic who died in 1752, has been credited with being the first one to advance this argument. 3 Novum Testamentum Graece, Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelstiftung, 26th ed., 1979. The Greek New Testament, New York: United Bible Societies, 3rd ed., 1975. The text of both these editions is virtually identical, having been elaborated by the same five editors: Kurt Aland, Matthew Black, Carlo Martini, Bruce Metzger and Allen Wikgren. -

Life and Letters of Brooke Foss Westcott Vol. I

ST. mars couKE LIFE AND LETTERS OF BROOKE FOSS WESTCOTT Life and Letters of Foss Westcott Brooke / D.D., D.C.L. Sometime Bishop of Durham BY HIS SON ARTHUR WESTCOTT WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. I 117252 ILonfcon MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1903 Ail rights reserved "To make of life one harmonious whole, to realise the invisible, to anticipate the transfiguring majesty of the Divine Presence, is all that is worth living for." B. F. \V. FRATRI NATU MAXIMO DOMUS NOSTRAE DUCI ET SIGNIFERO PATERNI NOMINIS IMPRIMIS STUDIOSO ET AD IPSIUS MEMORIAM SI OTIUM SUFFECISSET PER LITTERAS CELEBRANDAM PRAETER OMNES IDONEO HOC OPUSCULUM EIUS HORTATU SUSCEPTUM CONSILIIS AUCTUM ATQUE ADIUTUM D. D. D. FRATER NATU SECUNDUS. A. S., MCMIII. FRATKI NATU MAXIMO* 11ace tibi in re. ai<-o magni monnmcnta Parent is Maioi'i natu, frater, amo re pari. Si<jui'i inest dignnni, lactabere ; siquid ineptnm, Non milii tn censor sed, scio, [rater eris. Scis boif qnam duri fnerit res ilia laboris, Qnae melius per te suscipienda fiiit. 1 Tie diex, In nobis rcnoi'ali iwiinis /icres, Agtniw's ct nostri signifer unus eras. Scribcndo scd enim spatiiim, tibi sorte ncgatum, Iniporlnna minus fata dedcre mihi : Rt levin.: TISUDI cst infabrius arnia tulisse (Juain Patre pro tanto nil voluisse pati. lament: opus exaction cst quod, te sitadcnte, siibivi . Aecipc : indicia stctque cadatqne tno. Lcctorurn hand dnbia cst, reor, indulgentia. ; nalo Quodfrater frat ri tu dabis, ilia dabit. Xcc pctinins landcs : magnani depingerc vitani Ingcnio fatcor grandins ess.: nieo. Hoc erat in votis, nt, nos quod atnavinms, Hind Serns in cxtcrnis continnaret amor. -

Da Vinci Code Research

The Da Vinci Code Personal Unedited Research By: Josh McDowell © 2006 Overview Josh McDowell’s personal research on The Da Vinci Code was collected in preparation for the development of several equipping resources released in March 2006. This research is available as part of Josh McDowell’s Da Vinci Pastor Resource Kit. The full kit provides you with tools to equip your people to answer the questions raised by The Da Vinci Code book and movie. We trust that these resources will help you prepare your people with a positive readiness so that they might seize this as an opportunity to open up compelling dialogue about the real and relevant Christ. Da Vinci Pastor Resource Kit This kit includes: - 3-Part Sermon Series & Notes - Multi-media Presentation - Video of Josh's 3-Session Seminar on DVD - Sound-bites & Video Clip Library - Josh McDowell's Personal Research & Notes Retail Price: $49.95 The 3-part sermon series includes a sermon outline, discussion points and sample illustrations. Each session includes references to the slide presentation should you choose to include audio-visuals with your sermon series. A library of additional sound-bites and video clips is also included. Josh McDowell's delivery of a 3-session seminar was captured on video and is included in the kit. Josh's personal research and notes are also included. This extensive research is categorized by topic with side-by-side comparison to Da Vinci claims versus historical evidence. For more information and to order Da Vinci resources by Josh McDowell, visit josh.davinciquest.org. http://www.truefoundations.com Page 2 Table of Contents Introduction: The Search for Truth.................................................................................. -

Greg Goswell, “Early Readers of the Gospels: the KEPHALAIA and TITLOI of Codex Alexandrinus”

[JGRChJ 6 (2009) 134-74] EARLY READERS OF THE GOSPELS: THE KEPHALAIA AND TITLOI OF CODEX ALEXANDRINUS Greg Goswell Presbyterian Theological College, Melbourne, Australia For the New Testament, the oldest system of capitulation (division into chapters) known to us is that preserved in Codex Vaticanus (B 03) of the fourth century.1 I will use the notation V1, V2 etc. to refer to chapters of Vaticanus. Even a cursory examination of Vaticanus is enough to reveal that the divisions represent an evaluation of what are the sense units of the biblical passages. Each successive chapter in the Gospels is numbered using Greek letters written in red ink to the left of the columns. Capitulation is further indicated by a space of (usually) two letters at the close of the preceding chapter, a short horizontal line (paragraphos) above the first letter of the first whole line of the new chapter marking the close of the preceding paragraph, and sometimes by a letter protruding into the left margin (ekthesis).2 The system of 1. H.K. McArthur, ‘The Earliest Divisions of the Gospels’, in Studia Evangelica, III. 2 (ed. F.L. Cross; Texte und Untersuchungen, 88; Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1964), pp. 266-72. After rejecting three other possible explanations, McAr- thur suggests that the divisions were used for citation purposes, especially in aca- demic circles. For alternate systems of chapter division in Greek versions of the Old Testament, see Robert Devreesse, Introduction à l’étude des manuscrits grecs (Paris: Klincksieck, 1954), pp. 139-41. The major divisions in Vaticanus are called chapters, while those in Alexandrinus, which are the basis of the standard divisions used in Nestle-Aland (Novum Testamentum Graece [27th Edition] = NTG27) are called kephalaia. -

Codex Bezae (D05) in Light of P.Oxy. 4968 (127): a Reassessment of “Anti-Judaic Tendencies” in Acts 10–17

「성경원문연구」 41 (2017. 10.), 280-303 ISSN 1226-5926 (print), ISSN 2586-2480 (online) DOI: https://doi.org/10.28977/jbtr.2017.10.41.280 http://ibtr.bskorea.or.kr Codex Bezae (D05) in Light of P.Oxy. 4968 (127): A Reassessment of “Anti-Judaic Tendencies” in Acts 10–17 Hannah S. An* 1. Introduction Eldon Jay Epp’s classic monograph, The Theological Tendency of Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis in the Acts, marked a watershed moment in contemporary text-critical scholarship. Epp attempted to chart a coherent picture of the theological tendencies in Codex Bezae (D05) through a systematic treatment of the D-variants.1) He argues that underpinning the distinctive variants of the D-text (or the “Western” text)2) are the scribal tendencies of a Gentile Christian perspective that portray the Jews, and their leaders, as responsible for the death of Jesus, and hostile toward His apostles. Epp’s study has generated both positive and negative reactions in the field of New Testament textual criticism.3) * Ph.D. in Old Testament at Princeton Theological Seminary, USA. Assistant Professor of Old Testament at Torch Trinity Graduate University, Seoul. [email protected]. 1) E. J. Epp, The Theological Tendency of Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis in Acts, SNTS 3 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1966); “The ‘Ignorance Motif’ in Acts and Anti-Judaic Tendencies in Codex Bezae”, HTR 55 (1962), 51-62. Also see Epp’s recent reassessment of his own thesis in E. J. Epp, “Anti-Judaic Tendencies in the D-text of Acts: Forty Years of Conversation”, E. J. Epp, ed., Perspectives on New Testament Textual Criticism: Collected Essays, 1962-2004, SNT 116 (Leiden: Brill, 2005), 699-739. -

T.C. Skeat on the Dating and Origin of Codex Vaticanus

CHAPTER FIVE T.C. SKEAT ON THE DATING AND ORIGIN OF CODEX VATICANUS Biblical scholars are used to working with the text of Codex Sinaiticus [281] and Codex Vaticanus. We sometimes need to remind ourselves just how unique these manuscripts are. Both are codices on parchment that originally included the whole of the Bible. Even complete copies of the New Testament are rare: my count is only sixty-one manuscripts out of 5,000 New Testament manuscripts and not all those were originally composed as complete manuscripts; in some cases one of the sections was added by a different and later hand. Then the age of these manuscripts is remarkable—they are our oldest Bibles in Greek. (Their dates will be considered shortly.) The fact that they contain not only the New Testament but the com- plete Bible in Greek makes these, together with Codex Alexandrinus and Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus exceptional. Even Latin pandects are rare. The fifty Bibles ordered by Constantine (about which more below) must therefore have been a very high proportion of all the complete Bibles written during the fourth century or, indeed, ever written. The commonly agreed dates for Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus are fourth century; Alexandrinus and Ephraemi Rescriptus are from the fifth century. Cavallo1 suggested dates of 350 for Codex Vaticanus and 360 for Codex Sinaiticus—those suggestions by a famed expert ought to be weighed carefully. Kenyon2 gives the date as “early fourth century” for both. We ought to remind ourselves what was happening in the Christian world at that time. There was a growing consensus about the content of the Christian [282] scriptures—the finally agreed canon was being shaped. -

The 1909 Facsimile Edition of Codex Boernerianus

A Brief Introduction to This Digital Reproduction of Codex Boernerianus presented by: Mr. Gary S. Dykes 2007 [note: the images in this PDF file are compressed via the PDF process, and display not the original CD quality] image 090 - coded For years I desired a GOOD copy of codex 012. All I possessed was a microfiche copy, and reading many of the Latin portions in that microfiche was frustrating. 35mm film copies of the manuscript leave much to be desired, as they were poor reproductions of the facsimile edition. For years I tried to acquire a better copy. Whenever I saw a copy of the 1909 facsimile edition offered for sale, I attempted to purchase it (them) but was always too late (the sales occurred in Europe). Finally, in 2007, I found an excellent copy of the 1909 edition. One which was in pristine condition; no marks, no tears, no missing pages, cover original and fully intact! Not only this, but the printing was of excellent quality. Truly a copy worthy of preservation for all students, for now and future generations. Though I created this digital copy for my own personal use and work on I Corinthians, I realized that others could certainly use a copy. This particular facsimile edition had lain in a library (a very non- Christian institution); since 1910, the volume was checked out only once. It lay unused. Thus it remained in fine condition. Today it is now being shared with all, via the coöperation of the CSNTM website! As concerns the published volume: it was a very fine production, the color reproduction reflects some of the best I have ever seen for a facsimile edition. -

Copyright © 2013 Elijah Michael Hixson All Rights Reserved. the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary Has Permission to Reprod

Copyright © 2013 Elijah Michael Hixson All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. SCRIBAL TENDENCIES IN THE FOURTH GOSPEL IN CODEX ALEXANDRINUS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Theology by Elijah Michael Hixson May 2013 APPROVAL SHEET SCRIBAL TENDENCIES IN THE FOURTH GOSPEL IN CODEX ALEXANDRINUS Elijah Michael Hixson Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ Brian J. Vickers (Chair) __________________________________________ John B. Polhill Date______________________________ To my parents, Mike Hixson and Rachel Hayes TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE . xi Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY OF SCRIBAL TENDENCIES IN THE FOURTH GOSPEL IN CODEX ALEXANDRINUS . 1 A Description of Codex Alexandrinus . 1 Content and significance. 1 Name and history . 4 The scribes of Alexandrinus. 6 Kenyon’s five scribes. 7 Milne and Skeat’s two or three scribes . 7 Written by the hand of Thecla the Martyr? . 8 Scribal Habits through Singular Readings: A Short Summary. 9 2. MANUSCRIPT AND METHODOLOGY. 13 The Manuscript. 13 Method for Selecting Singular Readings . 14 Editions used. 14 Nomina sacra and orthography. 16 “Sub-singulars”. 18 Corrections . 18 Classification of Singular Readings . 20 Hernández’s study . 20 Insignificant singulars. 21 iv Chapter Page Significant singulars . 21 Inherited singulars. 22 Summary of classification. 23 Explanation of the Tables Used . 26 3. SINGULAR READINGS IN THE FOURTH GOSPEL IN CODEX ALEXANDRINUS. 29 Insignificant Singulars. 29 Orthographic singulars . -

The Order of the Gospels in the Parent of Codex Bezae. 339

J. Chapman, The order of the Gospels in the parent of Codex Bezae. 339 The order of the Gospels in the parent of Codex Bezae. By Dom J. Chapman, O. S. B. Erdington Abbey, Birmingham. Certain phenomena in Codex Bezae show that the Gospels are not given in the order of its archetype. They may be exhibited in the form of five arguments. It is to be remembered that the Gospels appear in the MS in the usual old Latin order: Mt Jo Lc MC. i. The punctuation of the MS consists "chiefly of a blank space between the words, or of a middle, sonietimes of an upper, very seldom of a lower single point, usually placed in the middle of a verse or crixoc, and found (äs in most other copies) much more thickly in some parts than in others: such a point is often set in the middle of a line, in passages whefe it is hard to see its use." So far Scrivener, p. xviii. Dr. Rendel Harris, on the other hand, has shown that the points, and perhaps the spaces, are traces of the original colometry of the arche- type, thus marked by the scribe, when he did not preserve the lines of his copy. Dr. Harris has pointed out their similarity to the points in the Curetonian Syriac and in the old Latin MS k (Study of Cod. Bezae, eh. xxiii; but contrast Burkitt, Evang. Da-Mepk. ii, p. 14). An examination of the points shows that they are very numerous in Matthew and in the early part of John.