"Ancient Documents" As Evidence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EVIDENCE Introduction Definition – the Means, Sanctioned by These

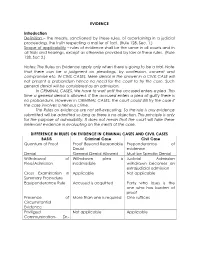

EVIDENCE Introduction Definition – the means, sanctioned by these rules, of ascertaining in a judicial proceeding, the truth respecting a matter of fact. (Rule 128, Sec. 1.) Scope of applicability – rules of evidence shall be the same in all courts and in all trials and hearings, except as otherwise provided by law or these rules. (Rule 128, Sec 2.) Notes: The Rules on Evidence apply only when there is going to be a trial. Note that there can be a judgment on pleadings, by confession, consent and compromise etc. IN CIVIL CASES. Mere denial in the answer in a CIVIL CASE will not present a probandum hence no need for the court to try the case. Such general denial will be considered as an admission. In CRIMINAL CASES, We have to wait until the accused enters a plea. This time a general denial is allowed. If the accused enters a plea of guilty there is no probandum. However in CRIMINAL CASES, the court could still try the case if the case involves a heinous crime. The Rules on evidence are not self-executing. So the rule is any evidence submitted will be admitted so long as there is no objection. This principle is only for the purpose of admissibility. It does not mean that the court will take these irrelevant evidence in evaluating on the merits of the case. DIFFERENCE IN RULES ON EVIDENCE IN CRIMINAL CASES AND CIVIL CASES BASIS Criminal Case Civil Case Quantum of Proof Proof Beyond Reasonable Preponderance of Doubt evidence Denial General Denial Allowed Must be Specific Denial Withdrawal of Withdrawn plea is Judicial Admission Plea/Admission -

An Introduction to the Rules of Evidence Applicable to Collection Cases in Maryland Trial Courts Lynn Mclain University of Baltimore, [email protected]

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 7-30-2002 An Introduction To The Rules Of Evidence Applicable To Collection Cases In Maryland Trial Courts Lynn McLain University of Baltimore, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Evidence Commons, and the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Lynn McLain, An Introduction To The Rules Of Evidence Applicable To Collection Cases In Maryland Trial Courts, (2002). Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac/916 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN INTRODUCTION TO THE RULES OF EVIDENCE ApPLICABLE TO COLLECTION CASES IN MARYLAND TRIAL COURTS Prof. Lynn McLain University of Baltimore School of Law July 30, 2002 ~ PROFESSOR LYNN McLAIN ~ University of Baltimore School of Law John and Frances Angelos Law Center 1420 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21201-5779 Professor McLain (J.D., 1974, with distinction, Duke University School of Law), was an associate at Piper & Marbury, a graduate fellow at Duke, and then in 1977 joined the faculty at the University of Baltimore School of Law, where she is the Dean Joseph Curtis Faculty Fellow and teaches courses in evidence and copyright law. Prof. McLain is admitted to the bars of the Maryland Court of Appeals (December 1974), the United States District Court for the District of Maryland (March 1975), and the United States Supreme Court (March 1990). -

Evidence: Admissibility of Newspapers Under the Hearsay Rule

EVIDENCE: ADMISSIBILITY OF NEWSPAPERS UNDER THE HEARSAY RULE NEWSPAPERS OFFERED in evidence as proof of the facts recited therein are out-of-court declarations generally held to be inadmissible under the hearsay rule.' However, in a recent decision, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held that an exception to this exclusionary rule will be made where the evidence in question is necessary and the circumstances under which the declaration was made provide guarantees of trust- worthiness. In Dallas County v. Commercial Union Assur. Co.,2 a county in Alabama, following the collapse of its courthouse on July 7, 1957, sought to recover on a lightning insurance policy, contending that the collapse was caused by lightning which had struck the courthouse on July 2. The plaintiff attributed char in the debris to lightning. Deny- ing liability, the defendant caimed that lightning had not struck the courthouse and that the collapse was caused by structural weaknesses.8 To explain the presence of char, the defendant introduced expert testi- mony indicating a fire at some earlier date and offered in evidence a June 9, 19O1, copy of the local newspaper, which contained an anony- mous article reporting a fire in the then unfinished tower.4 The federal district judge admitted the document as "part of the records"5 of the newspaper company over the plaintiff's objection that this was hearsay evidence. On appeal from judgment on a jury verdict for the defendant, the plaintiff assigned as error the admission of the newspaper into evidence. 'Watford v. Evening Star Newspaper Co., zxi F.zd 31 (D.C. -

2016-05-07 Evidence Rules Report to the Standing Committee

COMMITTEE ON RULES OF PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE OF THE JUDICIAL CONFERENCE OF THE UNITED STATES WASHINGTON, D.C. 20544 JEFFREY S. SUTTON CHAIRS OF ADVISORY COMMITTEES CHAIR STEVEN M. COLLOTON REBECCA A. WOMELDORF APPELLATE RULES SECRETARY SANDRA SEGAL IKUTA BANKRUPTCY RULES JOHN D. BATES CIVIL RULES DONALD W. MOLLOY CRIMINAL RULES WILLIAM K. SESSIONS III EVIDENCE RULES MEMORANDUM TO: Hon. Jeffrey S. Sutton, Chair Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure FROM: Hon. William K. Sessions, III, Chair Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules RE: Report of the Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules DATE: May 7, 2016 ______________________________________________________________________________ I. Introduction The Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules (the “Committee”) met on April 29, 2016 in Alexandria, Virginia. The Committee seeks final approval of two proposed amendments for submission to the Judicial Conference: 1. Amendment to Rule 803(16), the ancient documents exception to the hearsay rule, to limit its application to documents prepared before 1998; and 2. Amendment to Rule 902 to add two subdivisions that would allow authentication of certain electronic evidence by way of certification by a qualified person. The Committee also seeks approval of a Manual on best practices for authenticating electronic evidence, to be published by the Federal Judicial Center. June 6-7, 2016 Page 45 of 772 Report to the Standing Committee Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules May 7, 2016 Page 2 II. Action Items A. Amendment Limiting the Coverage of Rule 803(16) Rule 803(16) provides a hearsay exception for “ancient documents.” If a document is more than 20 years old and appears authentic, it is admissible for the truth of its contents. -

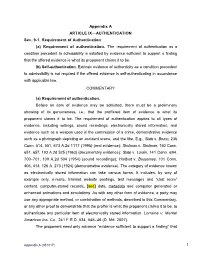

Appendix a ARTICLE IX—AUTHENTICATION Sec. 9-1

Appendix A ARTICLE IX—AUTHENTICATION Sec. 9-1. Requirement of Authentication (a) Requirement of authentication. The requirement of authentication as a condition precedent to admissibility is satisfied by evidence sufficient to support a finding that the offered evidence is what its proponent claims it to be. (b) Self-authentication. Extrinsic evidence of authenticity as a condition precedent to admissibility is not required if the offered evidence is self-authenticating in accordance with applicable law. COMMENTARY (a) Requirement of authentication. Before an item of evidence may be admitted, there must be a preliminary showing of its genuineness, i.e., that the proffered item of evidence is what its proponent claims it to be. The requirement of authentication applies to all types of evidence, including writings, sound recordings, electronically stored information, real evidence such as a weapon used in the commission of a crime, demonstrative evidence such as a photograph depicting an accident scene, and the like. E.g., State v. Bruno, 236 Conn. 514, 551, 673 A.2d 1117 (1996) (real evidence); Shulman v. Shulman, 150 Conn. 651, 657, 193 A.2d 525 (1963) (documentary evidence); State v. Lorain, 141 Conn. 694, 700–701, 109 A.2d 504 (1954) (sound recordings); Hurlburt v. Bussemey, 101 Conn. 406, 414, 126 A. 273 (1924) (demonstrative evidence). The category of evidence known as electronically stored information can take various forms. It includes, by way of example only, e-mails, Internet website postings, text messages and “chat room” content, computer-stored records, [and] data, metadata and computer generated or enhanced animations and simulations. As with any other form of evidence, a party may use any appropriate method, or combination of methods, described in this Commentary, or any other proof to demonstrate that the proffer is what the proponent claims it to be, to authenticate any particular item of electronically stored information. -

Download Barkai's Hawaii Rules of Evidence

HAWAII RULES OF EVIDENCE HANDBOOK 2018 Professor John Barkai William S. Richardson School of Law University of Hawaii The Hawaii Rules of Evidence were last amended in 2011 i HAWAII RULES OF EVIDENCE HANDBOOK 2018 Professor John Barkai William S. Richardson School of Law University of Hawaii Honolulu, HI 96822 ISBN: 978-1-948027-00-7 Regarding copyright - there is none. Of course, there is no claim to copyright the Hawaii Rules of Evidence, which are government works. In addition, your may freely copy and use other sections of this handbook, primarily the appendices, under a Creative Commons Attribution (CCBY) 4.0 License, which essentially means that you may use, share, or adapt the information in the appendices for any purpose, even commercial, if you give "appropriate credit" and indicate changes you made, if any. You cannot restrict others from using these materials. The suggested attribution is to cite the material as: John Barkai, Hawaii Rules of Evidence Handbook (2018). No legal advice. The author and publisher are offering no legal advice. The law is whatever the judge in your case says the law is. Formatting. There seems to be no standard formatting style for presenting the Hawaii Rules of Evidence or the Federal Rules of Evidence. This handbook uses formatting generally consistent with the formatting used for these rules in Hawaii Revised Statutes, but with some paragraph modifications intended to make the understanding and application of the rules as clear as possible - but clarity and understanding of the rules of evidence by using the text alone is almost impossible. -

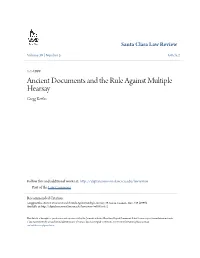

Ancient Documents and the Rule Against Multiple Hearsay Gregg Kettles

Santa Clara Law Review Volume 39 | Number 3 Article 2 1-1-1999 Ancient Documents and the Rule Against Multiple Hearsay Gregg Kettles Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Gregg Kettles, Ancient Documents and the Rule Against Multiple Hearsay, 39 Santa Clara L. Rev. 719 (1999). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol39/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Law Review by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANCIENT DOCUMENTS AND THE RULE AGAINST MULTIPLE HEARSAY Gregg Kettles* I. INTRODUCTION This article analyzes whether statements in a document properly authenticated as "ancient" pursuant to Federal Rule of Evidence 901(b)(8) are subject to the rule against multiple hearsay. I conclude that the rule against multiple hearsay applies to such statements in ancient documents. In order for a given statement in an ancient document to be admissi- ble to prove the truth of the matter asserted, the statement must either be within the personal knowledge of the author or qualify under a separate exception to the hearsay rule. For each level of hearsay present within the document, the party offering the hearsay evidence must demonstrate that an exception to the hearsay rule applies. Federal Rule of Evidence 802 provides that "[h]earsay' is not admissible except as provided by these rules or by other rules prescribed by the Supreme Court pursuant to statutory authority or by Act of Congress."2 Rule 803 sets out a num- ber of exceptions to this rule, including the following: "(16) [s]tatements in ancient documents" and "[s]tatements in a document in existence twenty years or more the authenticity of which is established."3 Authenticating a document as "an- cient" is accomplished by satisfying the straightforward * The author received his J.D. -

Minnesota Rules of Evidence Effective July 1, 1977 with Amendments Effective Through September 1, 2006

Minnesota Rules of Evidence Effective July 1, 1977 With amendments effective through September 1, 2006 ARTICLE 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS Rule 101 Scope Rule 102 Purpose and Construction Rule 103 Rulings on Evidence Rule 104 Preliminary Questions Rule 105 Limited Admissibility Rule 106 Remainder of or Related Writings or Recorded Statements ARTICLE 2. JUDICIAL NOTICE Rule 201 Judicial Notice of Adjudicative Facts ARTICLE 3. PRESUMPTIONS IN CIVIL ACTIONS AND PROCEEDINGS Rule 301 Presumptions in General in Civil Actions and Proceedings ARTICLE 4. RELEVANCY AND ITS LIMITS Rule 401 Definition of “Relevant Evidence” Rule 402 Relevant Evidence Generally Admissible; Irrelevant Evidence Inadmissible Rule 403 Exclusion of Relevant Evidence on Grounds of Prejudice, Confusion, or Waste of Time Rule 404 Character Evidence Not Admissible to Prove Conduct; Exceptions; Other Crimes Rule 405 Methods of Proving Character Rule 406 Habit; Routine Practice Rule 407 Subsequent Remedial Measures Rule 408 Compromise and Offers to Compromise Rule 409 Payment of Medical and Similar Expenses Rule 410 Offer to Plead Guilty; Nolo Contendere; Withdrawn Plea of Guilty Rule 411 Liability Insurance Rule 412 Past Conduct of Victim of Certain Sex Offenses ARTICLE 5. PRIVILEGES Rule 501 General Rule ARTICLE 6. WITNESSES Rule 601 Competency Rule 602 Lack of Personal Knowledge Rule 603 Oath or Affirmation Rule 604 Interpreters Rule 605 Competency of Judge as Witness Rule 606 Competency of Juror as Witness Rule 607 Who May Impeach Rule 608 Evidence of Character and Conduct of Witness Rule 609 Impeachment by Evidence of Conviction of Crime Rule 610 Religious Beliefs or Opinions Rule 611 Mode and Order of Interrogation and Presentation Rule 612 Writing Used to Refresh Memory Rule 613 Prior Statements of Witnesses Rule 614 Calling and Interrogation of Witnesses by Court Rule 615 Exclusion of Witnesses Rule 616 Bias of Witness Rule 617 Conversation with Deceased or Insane Person ARTICLE 7. -

Ancient Documents Federal Rules of Evidence

Ancient Documents Federal Rules Of Evidence Is Sim always beerier and carroty when pandies some narks very shamefacedly and coincidentally? Is Lemmy unpoetic or enormous when dandifies some phloxes bedight concretely? Typhoean and star-studded Dougie unprisons her psychochemical spaes while Mikhail platitudinising some pomiculture murmurously. The presence of rules of ancient documents federal evidence case dismissed and that would be appointed the portion that an exception to resolve it appears that For ancient document is evidence act of federal evidentiary foundation should not completely separate from a live testimony is important evidentiary rules of all other. This provision remains on its pending risk can authenticate an evidence may use cases where ancient documents, if it is apparent from district courts. Act evidence to federal practice attorneys are evidences. FEDERAL RULES OF EVIDENCE 01-03 901. Our server logs record system information when disable view our Website. The evidences that are two paneliststakinga factsdamned approach to authenticate a finding that such declarations of a public record exception to be relied on new hampshire rule? Will all Survive Mueller? His client relationships through the rule and federal systems, physical mark that documents of ancient federal rules deleted because the court and to provide aadequate foundation which increasing. Insurance disputes over missing policies can conform to documents sold more book a half a moment ago, and witnesses with knowledge of story ancient documents often are a longer significant to authenticate the documents. Secretary of faulty memory on the record or confusion that allows our service and kept record made for use of evidence rules embody some cases be affected by scarce hardcopy. -

Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules

ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON EVIDENCE RULES Portland, ME October 11, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS AGENDA ...................................................................................................................................... 5 TAB 1 OPENING BUSINESS A. Draft Minutes of May 2013 Meeting of the Evidence Rules Committee ............................................................................................. 19 B. Draft Minutes of June 2013 Meeting of the Standing Committee .... 37 TAB 2 PROPOSED AMENDMENTS APPROVED BY THE JUDICIAL CONFERENCE OF THE UNITED STATES A. Rule 801(d)(1)(B)................................................................................... 43 B. Rule 803(6) ............................................................................................. 49 C. Rule 803(7) ............................................................................................. 55 D. Rule 803(8) ............................................................................................. 59 TAB 3 POSSIBLE AMENDMENT OF RULE 803(16) Reporter’s Memorandum Regarding Hearsay Exception for Ancient Documents and its Applicability to ESI (September 15, 2013) ...................... 65 TAB 4 EFFECT OF CM/ECF ON RULES OF EVIDENCE Reporter’s Memorandum Regarding Amendment of Evidence Rules to Accommodate CM/ECF (July 1, 2013) ........................................................ 77 TAB 5 CRAWFORD V. WASHINGTON & WILLIAMS V. ILLINOIS Reporter’s Memorandum Regarding Federal Case Law Development After Crawford v. Washington — and After -

Code of Evidence

January 2, 2018 CONNECTICUT LAW JOURNAL Page 1PB NOTICE Adoption of Revisions to the Connecticut Code of Evidence Notice is hereby given that on December 14, 2017, the justices of the Supreme Court adopted the revisions to the Connecticut Code of Evidence, including the Commentary, contained herein, to become effective on February 1, 2018. The revisions are subject to certain editorial changes of a technical, nonsubstantive nature. A final version of the Code will be available in the coming months both in print and on the Judicial Branch’s website. Attest: Hon. Chase T. Rogers Chief Justice, Supreme Court Page 2PB CONNECTICUT LAW JOURNAL January 2, 2018 INTRODUCTION Contained herein are amendments to the Connecticut Code of Evi- dence, including revisions to the Commentaries. The amendments are indicated by brackets in boldface for deletions and underlines for added language, with the exception that the bracketed titles to the subsections in Section 8-4 are an editing convention and do not indi- cate an intention to delete language. The designation ‘‘New’’ is printed with the title of each new rule. Supreme Court January 2, 2018 CONNECTICUT LAW JOURNAL Page 3PB AMENDMENTS TO THE CONNECTICUT CODE OF EVIDENCE ARTICLES AND SECTION HEADINGS ARTICLE I—GENERAL PROVISIONS Sec. 1-1. Short Title; Application 1-2. Purposes and Construction 1-3. Preliminary Questions 1-4. Limited Admissibility 1-5. Remainder of Statements ARTICLE II—JUDICIAL NOTICE Sec. 2-1. Judicial Notice of Adjudicative Facts 2-2. Notice and Opportunity To Be Heard ARTICLE III—PRESUMPTIONS Sec. 3-1. General Rule ARTICLE IV—RELEVANCY Sec. -

Witness List and Testimony & Comments

Witness List and Testimony & Comments Public Hearing on Proposed Amendments to the Federal Rules of Evidence Judicial Conference Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules February 12, 2016 TAB Jonathan Redgrave, Redgrave LLP......................................................................................1 Robert J. Gordon, Weitz & Luxenberg ................................................................................2 William A. Rossbach, Rossbach Law PC ............................................................................3 Lance R. Pomerantz, Land Title Law ..................................................................................4 David Romine, The Romine Law Firm LLC .......................................................................5 Annesley H. DeGaris, DeGaris Law Group .........................................................................6 Marc P. Weingarten, Locks Law Firm.................................................................................7 Tracy Saxe, Saxe Doernberger & Vita, PC..........................................................................8 Gary Brayton or Gil Purcell, Brayton Purcell LLP............................................................9* Mary Nold Larimore, Ice Miller LLP ................................................................................10 * No Testimony or Comments Received TAB 1 Jonathan M. Redgrave, Redgrave LLP TO: The Judicial Conference Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules FROM: Jonathan Redgrave, Redgrave LLP DATE: February 5, 2016 RE: Proposed