Ancient Documents and the Rule Against Multiple Hearsay Gregg Kettles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michigan Rules of Evidence Table of Contents

Michigan Rules of Evidence Table of Contents RULES 101–106 .......................................................................................................... 4 Rule 101. Scope. ....................................................................................................... 4 Rule 102. Purpose. ................................................................................................... 4 Rule 103. Rulings on Evidence. ............................................................................... 4 Rule 104. Preliminary Questions. ........................................................................... 5 Rule 105. Limited Admissibility. ............................................................................. 5 Rule 106. Remainder of or Related Writings or Recorded Statements. ................. 5 RULES 201–202 .......................................................................................................... 5 Rule 201. Judicial Notice of Adjudicative Facts. .................................................... 5 Rule 202. Judicial Notice of Law. ............................................................................ 6 RULES 301–302 .......................................................................................................... 6 Rule 301. Presumptions in Civil Actions and Proceedings. ................................... 6 Rule 302. Presumptions in Criminal Cases. ........................................................... 6 RULES 401–411 ......................................................................................................... -

Rule 803. Hearsay Exceptions; Availability of Declarant Immaterial. the Following Are Not Excluded by the Hearsay Rule, Even Th

Article 8. Hearsay. Rule 801. Definitions and exception for admissions of a party-opponent. The following definitions apply under this Article: (a) Statement. – A "statement" is (1) an oral or written assertion or (2) nonverbal conduct of a person, if it is intended by him as an assertion. (b) Declarant. – A "declarant" is a person who makes a statement. (c) Hearsay. – "Hearsay" is a statement, other than one made by the declarant while testifying at the trial or hearing, offered in evidence to prove the truth of the matter asserted. (d) Exception for Admissions by a Party-Opponent. – A statement is admissible as an exception to the hearsay rule if it is offered against a party and it is (A) his own statement, in either his individual or a representative capacity, or (B) a statement of which he has manifested his adoption or belief in its truth, or (C) a statement by a person authorized by him to make a statement concerning the subject, or (D) a statement by his agent or servant concerning a matter within the scope of his agency or employment, made during the existence of the relationship or (E) a statement by a coconspirator of such party during the course and in furtherance of the conspiracy. (1983, c. 701, s. 1.) Rule 802. Hearsay rule. Hearsay is not admissible except as provided by statute or by these rules. (1983, c. 701, s. 1.) Rule 803. Hearsay exceptions; availability of declarant immaterial. The following are not excluded by the hearsay rule, even though the declarant is available as a witness: (1) Present Sense Impression. -

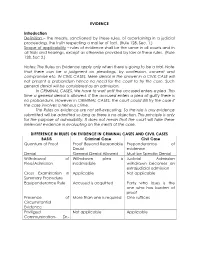

EVIDENCE Introduction Definition – the Means, Sanctioned by These

EVIDENCE Introduction Definition – the means, sanctioned by these rules, of ascertaining in a judicial proceeding, the truth respecting a matter of fact. (Rule 128, Sec. 1.) Scope of applicability – rules of evidence shall be the same in all courts and in all trials and hearings, except as otherwise provided by law or these rules. (Rule 128, Sec 2.) Notes: The Rules on Evidence apply only when there is going to be a trial. Note that there can be a judgment on pleadings, by confession, consent and compromise etc. IN CIVIL CASES. Mere denial in the answer in a CIVIL CASE will not present a probandum hence no need for the court to try the case. Such general denial will be considered as an admission. In CRIMINAL CASES, We have to wait until the accused enters a plea. This time a general denial is allowed. If the accused enters a plea of guilty there is no probandum. However in CRIMINAL CASES, the court could still try the case if the case involves a heinous crime. The Rules on evidence are not self-executing. So the rule is any evidence submitted will be admitted so long as there is no objection. This principle is only for the purpose of admissibility. It does not mean that the court will take these irrelevant evidence in evaluating on the merits of the case. DIFFERENCE IN RULES ON EVIDENCE IN CRIMINAL CASES AND CIVIL CASES BASIS Criminal Case Civil Case Quantum of Proof Proof Beyond Reasonable Preponderance of Doubt evidence Denial General Denial Allowed Must be Specific Denial Withdrawal of Withdrawn plea is Judicial Admission Plea/Admission -

Benjamin Gutman #160599 Kristin A

May 8, 2018 02:27 PM IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF OREGON STATE OF OREGON, Clackamas County Circuit Court Case No. CR1400136 Plaintiff-Respondent, Respondent on Review, CA A158854 v. S065355 KELLY LEE EDMONDS, Defendant-Appellant Petitioner on Review. PETITIONER’S BRIEF ON THE MERITS Review the decision of the Court of Appeals on Appeal from a Judgment of the Circuit Court for Clackamas County Honorable Douglas V. Van Dyk, Judge Opinion Filed: June 1, 2017 Author of Opinion: Linder, S. J. Concurring Judges: Tookey, Presiding Judge, and Shorr, Judge, ERNEST G. LANNET #013248 ELLEN F. ROSENBLUM #753239 Chief Defender Attorney General Criminal Appellate Section BENJAMIN GUTMAN #160599 KRISTIN A. CARVETH #052157 Solicitor General Senior Deputy Public Defender DAVID B. THOMPSON #951246 Office of Public Defense Services Assistant Attorney General 1175 Court Street NE 400 Justice Building Salem, OR 97301 1162 Court Street NE [email protected] Salem, OR 97301 Phone: (503) 378-3349 [email protected] Attorneys for Petitioner on Review Phone: (503) 378-4402 Attorneys for Respondent on Review 63739 05/18 i TABLE OF CONTENTS STATEMENT OF THE CASE ............................................................................ 1 Questions Presented and Proposed Rules of Law .......................................... 2 Summary of Argument .................................................................................. 4 Historical and Procedural Facts .................................................................... -

An Introduction to the Rules of Evidence Applicable to Collection Cases in Maryland Trial Courts Lynn Mclain University of Baltimore, [email protected]

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 7-30-2002 An Introduction To The Rules Of Evidence Applicable To Collection Cases In Maryland Trial Courts Lynn McLain University of Baltimore, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Evidence Commons, and the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Lynn McLain, An Introduction To The Rules Of Evidence Applicable To Collection Cases In Maryland Trial Courts, (2002). Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac/916 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN INTRODUCTION TO THE RULES OF EVIDENCE ApPLICABLE TO COLLECTION CASES IN MARYLAND TRIAL COURTS Prof. Lynn McLain University of Baltimore School of Law July 30, 2002 ~ PROFESSOR LYNN McLAIN ~ University of Baltimore School of Law John and Frances Angelos Law Center 1420 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21201-5779 Professor McLain (J.D., 1974, with distinction, Duke University School of Law), was an associate at Piper & Marbury, a graduate fellow at Duke, and then in 1977 joined the faculty at the University of Baltimore School of Law, where she is the Dean Joseph Curtis Faculty Fellow and teaches courses in evidence and copyright law. Prof. McLain is admitted to the bars of the Maryland Court of Appeals (December 1974), the United States District Court for the District of Maryland (March 1975), and the United States Supreme Court (March 1990). -

"Ancient Documents" As Evidence

The Archivist and "Ancient Documents" as Evidence Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/26/4/487/2744520/aarc_26_4_148255750366p7l6.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 By CYRUS B. KING* D. H. Hill Library N. C. State of the University of North Carolina at Raleigh GENERATION or more after the occurrence of a certain event, when all of the witnesses have passed from the scene, A litigation stemming from that event normally must proceed on the basis of documents created contemporaneously with the event. As the custodian of needed documents, an archivist may very well find himself embroiled in litigation that requires the use of evidentiary documents in his care. The archivist's involve- ment ordinarily results from the question of custody, one of the several conditions affecting the admissibility of a document as evidence in a court of law under the common-law ancient documents rule. For some three centuries judges have accepted the validity of the common-law rule that an ancient document, under certain con- ditions, may be taken as sufficiently genuine to be submitted to a jury as evidence without further authentication of its genuineness.1 The reason for such a rule, of course, is the impossibility of ob- taining living testimony to prove that the document is indeed gen- uine. Until a certain lapse of time, after which all of the living witnesses are gone, there is no necessity for the application of the rule. From such necessity evolved the common-law ancient documents rule. At first the requirement -

Ohio Rules of Evidence

OHIO RULES OF EVIDENCE Article I GENERAL PROVISIONS Rule 101 Scope of rules: applicability; privileges; exceptions 102 Purpose and construction; supplementary principles 103 Rulings on evidence 104 Preliminary questions 105 Limited admissibility 106 Remainder of or related writings or recorded statements Article II JUDICIAL NOTICE 201 Judicial notice of adjudicative facts Article III PRESUMPTIONS 301 Presumptions in general in civil actions and proceedings 302 [Reserved] Article IV RELEVANCY AND ITS LIMITS 401 Definition of “relevant evidence” 402 Relevant evidence generally admissible; irrelevant evidence inadmissible 403 Exclusion of relevant evidence on grounds of prejudice, confusion, or undue delay 404 Character evidence not admissible to prove conduct; exceptions; other crimes 405 Methods of proving character 406 Habit; routine practice 407 Subsequent remedial measures 408 Compromise and offers to compromise 409 Payment of medical and similar expenses 410 Inadmissibility of pleas, offers of pleas, and related statements 411 Liability insurance Article V PRIVILEGES 501 General rule Article VI WITNESS 601 General rule of competency 602 Lack of personal knowledge 603 Oath or affirmation Rule 604 Interpreters 605 Competency of judge as witness 606 Competency of juror as witness 607 Impeachment 608 Evidence of character and conduct of witness 609 Impeachment by evidence of conviction of crime 610 Religious beliefs or opinions 611 Mode and order of interrogation and presentation 612 Writing used to refresh memory 613 Impeachment by self-contradiction -

Evidence: Admissibility of Newspapers Under the Hearsay Rule

EVIDENCE: ADMISSIBILITY OF NEWSPAPERS UNDER THE HEARSAY RULE NEWSPAPERS OFFERED in evidence as proof of the facts recited therein are out-of-court declarations generally held to be inadmissible under the hearsay rule.' However, in a recent decision, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held that an exception to this exclusionary rule will be made where the evidence in question is necessary and the circumstances under which the declaration was made provide guarantees of trust- worthiness. In Dallas County v. Commercial Union Assur. Co.,2 a county in Alabama, following the collapse of its courthouse on July 7, 1957, sought to recover on a lightning insurance policy, contending that the collapse was caused by lightning which had struck the courthouse on July 2. The plaintiff attributed char in the debris to lightning. Deny- ing liability, the defendant caimed that lightning had not struck the courthouse and that the collapse was caused by structural weaknesses.8 To explain the presence of char, the defendant introduced expert testi- mony indicating a fire at some earlier date and offered in evidence a June 9, 19O1, copy of the local newspaper, which contained an anony- mous article reporting a fire in the then unfinished tower.4 The federal district judge admitted the document as "part of the records"5 of the newspaper company over the plaintiff's objection that this was hearsay evidence. On appeal from judgment on a jury verdict for the defendant, the plaintiff assigned as error the admission of the newspaper into evidence. 'Watford v. Evening Star Newspaper Co., zxi F.zd 31 (D.C. -

OVERVIEW of WRITTEN RECORDS EXCEPTIONS, FRE 803 (5) Et Seq

17. WRITTEN RECORDS EXCEPTIONS, FRE 803 (5) et seq. A. OVERVIEW 1. There are lots of exceptions for written documents found in Rule 803. We will focus on the two most important ones: a) Records of a Regularly Conducted Activity, 803(6), which most people call by its nickname, Business Records. b) Public records, 803(8), also sometimes called official records 2. These exceptions are tricky because there is a tendency to confuse the name of the rule with whether it fits into an exception. A document is not a “business record” because it is the record of a business, nor is it a “public record” because it comes from a government office. The only question is whether the foundation has been laid, and they are detailed. A document is only a piece of paper until someone lays a foundation. If you're suing the welfare dept, and trying to get their records into evidence, they could be business records, official records, statements of the opposing party, past recollection recorded, or not hearsay at all because not offered for their truth, depending on the circumstances and what kind of foundation you can lay. 3. These records frequently have hearsay within hearsay problems . Business records may describe both the personal knowledge of employees and also things told to employees by outsiders. The former is covered by the business record exception, the latter is not. It needs its own reason why it is not hearsay. 4. You must distinguish business records from documents with independent legal significance, from admissions of the party-opponent. -

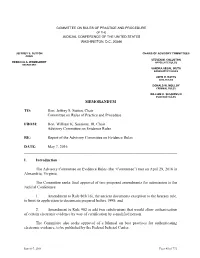

2016-05-07 Evidence Rules Report to the Standing Committee

COMMITTEE ON RULES OF PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE OF THE JUDICIAL CONFERENCE OF THE UNITED STATES WASHINGTON, D.C. 20544 JEFFREY S. SUTTON CHAIRS OF ADVISORY COMMITTEES CHAIR STEVEN M. COLLOTON REBECCA A. WOMELDORF APPELLATE RULES SECRETARY SANDRA SEGAL IKUTA BANKRUPTCY RULES JOHN D. BATES CIVIL RULES DONALD W. MOLLOY CRIMINAL RULES WILLIAM K. SESSIONS III EVIDENCE RULES MEMORANDUM TO: Hon. Jeffrey S. Sutton, Chair Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure FROM: Hon. William K. Sessions, III, Chair Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules RE: Report of the Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules DATE: May 7, 2016 ______________________________________________________________________________ I. Introduction The Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules (the “Committee”) met on April 29, 2016 in Alexandria, Virginia. The Committee seeks final approval of two proposed amendments for submission to the Judicial Conference: 1. Amendment to Rule 803(16), the ancient documents exception to the hearsay rule, to limit its application to documents prepared before 1998; and 2. Amendment to Rule 902 to add two subdivisions that would allow authentication of certain electronic evidence by way of certification by a qualified person. The Committee also seeks approval of a Manual on best practices for authenticating electronic evidence, to be published by the Federal Judicial Center. June 6-7, 2016 Page 45 of 772 Report to the Standing Committee Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules May 7, 2016 Page 2 II. Action Items A. Amendment Limiting the Coverage of Rule 803(16) Rule 803(16) provides a hearsay exception for “ancient documents.” If a document is more than 20 years old and appears authentic, it is admissible for the truth of its contents. -

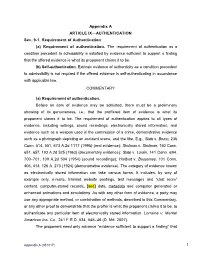

Appendix a ARTICLE IX—AUTHENTICATION Sec. 9-1

Appendix A ARTICLE IX—AUTHENTICATION Sec. 9-1. Requirement of Authentication (a) Requirement of authentication. The requirement of authentication as a condition precedent to admissibility is satisfied by evidence sufficient to support a finding that the offered evidence is what its proponent claims it to be. (b) Self-authentication. Extrinsic evidence of authenticity as a condition precedent to admissibility is not required if the offered evidence is self-authenticating in accordance with applicable law. COMMENTARY (a) Requirement of authentication. Before an item of evidence may be admitted, there must be a preliminary showing of its genuineness, i.e., that the proffered item of evidence is what its proponent claims it to be. The requirement of authentication applies to all types of evidence, including writings, sound recordings, electronically stored information, real evidence such as a weapon used in the commission of a crime, demonstrative evidence such as a photograph depicting an accident scene, and the like. E.g., State v. Bruno, 236 Conn. 514, 551, 673 A.2d 1117 (1996) (real evidence); Shulman v. Shulman, 150 Conn. 651, 657, 193 A.2d 525 (1963) (documentary evidence); State v. Lorain, 141 Conn. 694, 700–701, 109 A.2d 504 (1954) (sound recordings); Hurlburt v. Bussemey, 101 Conn. 406, 414, 126 A. 273 (1924) (demonstrative evidence). The category of evidence known as electronically stored information can take various forms. It includes, by way of example only, e-mails, Internet website postings, text messages and “chat room” content, computer-stored records, [and] data, metadata and computer generated or enhanced animations and simulations. As with any other form of evidence, a party may use any appropriate method, or combination of methods, described in this Commentary, or any other proof to demonstrate that the proffer is what the proponent claims it to be, to authenticate any particular item of electronically stored information. -

Download Barkai's Hawaii Rules of Evidence

HAWAII RULES OF EVIDENCE HANDBOOK 2018 Professor John Barkai William S. Richardson School of Law University of Hawaii The Hawaii Rules of Evidence were last amended in 2011 i HAWAII RULES OF EVIDENCE HANDBOOK 2018 Professor John Barkai William S. Richardson School of Law University of Hawaii Honolulu, HI 96822 ISBN: 978-1-948027-00-7 Regarding copyright - there is none. Of course, there is no claim to copyright the Hawaii Rules of Evidence, which are government works. In addition, your may freely copy and use other sections of this handbook, primarily the appendices, under a Creative Commons Attribution (CCBY) 4.0 License, which essentially means that you may use, share, or adapt the information in the appendices for any purpose, even commercial, if you give "appropriate credit" and indicate changes you made, if any. You cannot restrict others from using these materials. The suggested attribution is to cite the material as: John Barkai, Hawaii Rules of Evidence Handbook (2018). No legal advice. The author and publisher are offering no legal advice. The law is whatever the judge in your case says the law is. Formatting. There seems to be no standard formatting style for presenting the Hawaii Rules of Evidence or the Federal Rules of Evidence. This handbook uses formatting generally consistent with the formatting used for these rules in Hawaii Revised Statutes, but with some paragraph modifications intended to make the understanding and application of the rules as clear as possible - but clarity and understanding of the rules of evidence by using the text alone is almost impossible.