Minnesota Rules of Evidence Effective July 1, 1977 with Amendments Effective Through September 1, 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best Evidence Rule--Oral Proof of Contents of Writings

St. John's Law Review Volume 5 Number 2 Volume 5, May 1931, Number 2 Article 8 Best Evidence Rule--Oral Proof of Contents of Writings Thomas M. McDade Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. John's Law Review by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES AND COMMENT ing certain modes of procedure, in federal cases, it is submitted that there is nothing in the Fourteenth Amendment that forbids a state from keeping its rules of procedure and evidence abreast of the most enlightened views of modern jurisprudence. C. JOSEPHa DANAHY. BEST EVIDENCE RULE-ORAL PROOF OF CONTENTS OF WRITINGS. It is common learning in the law of evidence that a writing or document is the best evidence of what it contains. "Indeed the term 'best evidence' has been described as a convenient short de- scription of the rule as to proving the contents of a writing." I Therefore, generally, oral testimony will not be admitted to prove what was contained in a writing; the document itself must be produced and offered in evidence.2 The reasons for this rule are founded on the uncertainty of oral testimony based on recollec- tion, and the inability to reproduce properly such characteristics as form, handwriting and physical appearance. 3 But, like most laws of a pseudo-science, this general rule has several exceptions, and it is with one of these exceptions that we are concerned. -

Michigan Rules of Evidence Table of Contents

Michigan Rules of Evidence Table of Contents RULES 101–106 .......................................................................................................... 4 Rule 101. Scope. ....................................................................................................... 4 Rule 102. Purpose. ................................................................................................... 4 Rule 103. Rulings on Evidence. ............................................................................... 4 Rule 104. Preliminary Questions. ........................................................................... 5 Rule 105. Limited Admissibility. ............................................................................. 5 Rule 106. Remainder of or Related Writings or Recorded Statements. ................. 5 RULES 201–202 .......................................................................................................... 5 Rule 201. Judicial Notice of Adjudicative Facts. .................................................... 5 Rule 202. Judicial Notice of Law. ............................................................................ 6 RULES 301–302 .......................................................................................................... 6 Rule 301. Presumptions in Civil Actions and Proceedings. ................................... 6 Rule 302. Presumptions in Criminal Cases. ........................................................... 6 RULES 401–411 ......................................................................................................... -

4.08 “Open Door” Evidence (1) a Party

4.08 “Open Door” Evidence (1) A party may “open the door” to the introduction by an opposing party of evidence that would otherwise be inadmissible when in the presentation of argument, cross-examination of a witness, or other presentation of evidence the party has given an incomplete and misleading impression on an issue. (2) A trial court must exercise its discretion to decide whether a party has “opened the door” to otherwise inadmissible evidence. In so doing, the trial court should consider whether, and to what extent, the evidence or argument claimed to “open the door” is incomplete and misleading and what, if any, otherwise inadmissible evidence is reasonably necessary to explain, clarify, or otherwise correct an incomplete and misleading impression. (3) To assure the proper exercise of the court’s discretion and avoid the introduction of otherwise inadmissible evidence, the recommended practice is for a party to apply to the trial court for a ruling on whether the door has been opened before proceeding forward, and the court should so advise the parties before taking evidence. Note Subdivisions (1) and (2) recite the long-settled “open door” principle in New York, as primarily explained in People v Melendez (55 NY2d 445 [1982]); People v Rojas (97 NY2d 32, 34 [2001]); People v Massie (2 NY3d 179 [2004]); and People v Reid (19 NY3d 382 [2012]). Melendez dealt with the issue of whether the defense had opened the door to permit the prosecutor to explore an aspect of the investigation that would not otherwise have been admissible. The Court began by noting that, when an “opposing party ‘opens the door’ on cross-examination to matters not touched upon during the direct examination, a party has the right on redirect to explain, clarify and fully elicit [the] question only partially examined on cross-examination.” (Melendez at 451 1 [internal quotation marks and citation omitted].) Argument to the jury or other presentation of evidence also may open the door to the admission of otherwise inadmissible evidence. -

The Epistemology of Evidence in Cognitive Neuroscience1

To appear in In R. Skipper Jr., C. Allen, R. A. Ankeny, C. F. Craver, L. Darden, G. Mikkelson, and R. Richardson (eds.), Philosophy and the Life Sciences: A Reader. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. The Epistemology of Evidence in Cognitive Neuroscience1 William Bechtel Department of Philosophy and Science Studies University of California, San Diego 1. The Epistemology of Evidence It is no secret that scientists argue. They argue about theories. But even more, they argue about the evidence for theories. Is the evidence itself trustworthy? This is a bit surprising from the perspective of traditional empiricist accounts of scientific methodology according to which the evidence for scientific theories stems from observation, especially observation with the naked eye. These accounts portray the testing of scientific theories as a matter of comparing the predictions of the theory with the data generated by these observations, which are taken to provide an objective link to reality. One lesson philosophers of science have learned in the last 40 years is that even observation with the naked eye is not as epistemically straightforward as was once assumed. What one is able to see depends upon one’s training: a novice looking through a microscope may fail to recognize the neuron and its processes (Hanson, 1958; Kuhn, 1962/1970).2 But a second lesson is only beginning to be appreciated: evidence in science is often not procured through simple observations with the naked eye, but observations mediated by complex instruments and sophisticated research techniques. What is most important, epistemically, about these techniques is that they often radically alter the phenomena under investigation. -

Is There a Role for Proof of Character, Propensity, Or Prior Bad Conduct in Medical Negligence Litigation?, 63 S.C

UIC School of Law UIC Law Open Access Repository UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2011 Good Medicine/Bad Medicine And The Law Of Evidence: Is There A Role For Proof Of Character, Propensity, Or Prior Bad Conduct In Medical Negligence Litigation?, 63 S.C. L. Rev. 367 (2011) Marc Ginsberg The John Marshall Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs Part of the Evidence Commons, Health Law and Policy Commons, Litigation Commons, Medical Jurisprudence Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Marc Ginsberg, Good Medicine/Bad Medicine And The Law Of Evidence: Is There A Role For Proof Of Character, Propensity, Or Prior Bad Conduct In Medical Negligence Litigation?, 63 S.C. L. Rev. 367 (2011) https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs/352 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOOD MEDICINE/BAD MEDICINE AND THE LAW OF EVIDENCE: Is THERE A ROLE FOR PROOF OF CHARACTER, PROPENSITY, OR PRIOR BAD CONDUCT IN MEDICAL NEGLIGENCE LITIGATION? Marc D. Ginsberg* I. IN TRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 368 II. RULES OF EVIDENCE INVOLVED .................................................................. 370 111. PHYSICIAN REPUTATION ............................................................................. 373 IV. PRIOR LAWSUITS AGAINST THE PHYSICIAN DEFENDANT ........................... 378 V. EVIDENCE OF PHYSICIAN TREATMENT OF OTHER PATIENTS- IN AD M ISSIB LE ............................................................................................. 380 VI. EVIDENCE OF PHYSICIAN TREATMENT OF OTHER PATIENTS- A D M ISSIB LE ............................................................................................... -

The Applicability of the Character Evidence Rule to Corporations

KIM.DOC 12/20/00 2:32 PM CHARACTERISTICS OF SOULLESS PERSONS: THE APPLICABILITY OF THE CHARACTER EVIDENCE RULE TO CORPORATIONS ∗ Susanna M. Kim Under Federal Rule of Evidence 404, the character evidence rule, it is well established that evidence of character generally is not admissible to show that a person acted in conformity with that char- acter on a particular occasion. No consensus exists, however, as to whether the character evidence rule should also apply to corpora- tions. In this article, Professor Kim argues that the ban on character evidence should not be extended to corporations. Professor Kim be- gins with a discussion of various rationales offered to support the character evidence rule, emphasizing Kantian conceptions of human autonomy. She then examines varying definitions of “character” and concludes that character may best be regarded as a reflection of the internal operating system of the human organism. Next, Professor Kim turns to an analysis of the personhood of corporations and de- termines that corporations are persons and moral actors with the ca- pacity to possess character. This corporate character is separate and apart from the character of the corporation’s individual members and reflects the internal operating system of the corporate organization. Finally, Professor Kim suggests that the human autonomy ra- tionale for the character evidence rule does not apply with equal force to corporations. She then concludes with an examination of the prac- tical implications of excluding corporations from the protections af- forded individuals under Rule 404. To a seemingly ever-increasing extent the members of society, individual and corporate alike, are awash in an existential sea, out ∗ Associate Professor of Law, Chapman University School of Law. -

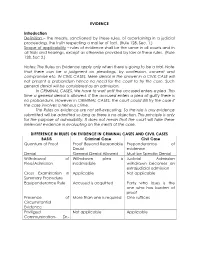

EVIDENCE Introduction Definition – the Means, Sanctioned by These

EVIDENCE Introduction Definition – the means, sanctioned by these rules, of ascertaining in a judicial proceeding, the truth respecting a matter of fact. (Rule 128, Sec. 1.) Scope of applicability – rules of evidence shall be the same in all courts and in all trials and hearings, except as otherwise provided by law or these rules. (Rule 128, Sec 2.) Notes: The Rules on Evidence apply only when there is going to be a trial. Note that there can be a judgment on pleadings, by confession, consent and compromise etc. IN CIVIL CASES. Mere denial in the answer in a CIVIL CASE will not present a probandum hence no need for the court to try the case. Such general denial will be considered as an admission. In CRIMINAL CASES, We have to wait until the accused enters a plea. This time a general denial is allowed. If the accused enters a plea of guilty there is no probandum. However in CRIMINAL CASES, the court could still try the case if the case involves a heinous crime. The Rules on evidence are not self-executing. So the rule is any evidence submitted will be admitted so long as there is no objection. This principle is only for the purpose of admissibility. It does not mean that the court will take these irrelevant evidence in evaluating on the merits of the case. DIFFERENCE IN RULES ON EVIDENCE IN CRIMINAL CASES AND CIVIL CASES BASIS Criminal Case Civil Case Quantum of Proof Proof Beyond Reasonable Preponderance of Doubt evidence Denial General Denial Allowed Must be Specific Denial Withdrawal of Withdrawn plea is Judicial Admission Plea/Admission -

Preserving the Record

Chapter Seven: Preserving the Record Edward G. O’Connor, Esquire Patrick R. Kingsley, Esquire Echert Seamans Cherin & Mellot Pittsburgh PRESERVING THE RECORD I. THE IMPORTANCE OF PRESERVING THE RECORD. Evidentiary rulings are seldom the basis for a reversal on appeal. Appellate courts are reluctant to reverse because of an error in admitting or excluding evidence, and sometimes actively search for a way to hold that a claim of error in an evidence ruling is barred. R. Keeton, Trial Tactics and Methods, 191 (1973). It is important, therefore, to preserve the record in the trial court to avoid giving the Appellate Court the opportunity to ignore your claim of error merely because of a technicality. II. PRESERVING THE RECORD WHERE THE TRIAL COURT HAS LET IN YOUR OPPONENT’S EVIDENCE. A. The Need to Object: 1. Preserving the Issue for Appeal. A failure to object to the admission of evidence ordinarily constitutes a waiver of the right to object to the admissibility or use of that evidence. Taylor v. Celotex Corp., 393 Pa. Super. 566, 574 A.2d 1084 (1990). If there is no objection, the court is not obligated to exclude improper evidence being offered. Errors in admitting evidence at trial are usually waived on appeal unless a proper, timely objection was made during the trial. Commonwealth v. Collins, 492 Pa. 405, 424 A.2d 1254 (1981). The rules of appellate procedure are meant to afford the trial judge an opportunity to correct any mistakes that have been made before these mistakes can be a basis of appeal. A litigator will not be allowed to ambush the trial judge by remaining silent at trial and voice an objection to the Appellate Court only after an unfavorable verdict or judgment is reached. -

Using Leading Questions During Direct Examination

Florida State University Law Review Volume 23 Issue 2 Article 4 Fall 1995 Using Leading Questions During Direct Examination Charles W. Ehrhardt Florida State University College of Law Stephanie J. Young Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Evidence Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Charles W. Ehrhardt & Stephanie J. Young, Using Leading Questions During Direct Examination, 23 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 401 (1995) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol23/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. USING LEADING QUESTIONS DURING DIRECT EXAMINATION CHARLES W. EHRHARDT* AND STEPHANIE J. YOUNG"* I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................... 401 II. BEFORE ADOPTION OF FLORIDA'S EVIDENCE CODE ......... 402 A. An Exception for Leading Questions on Direct Examination ................................................ 402 B. Voucher Rule Barred Impeaching a Party'sOwn Witness ....................................................... 404 III. ADOPTION OF FLORIDA'S EVIDENCE CODE ................... 405 A. Section 90.608: Impeaching an Adverse Witness... 405 B. Section 90.612(3): Use of Leading Questions ....... 406 C. 1990 Amendment to Section 90.608 ................... 408 D. Evidence Code Amendments Make Rule Unnecessary................................................ -

Best Evidence Rule Chapter

Evidence: Best Evidence Rule Colin Miller CALI eLangdell® Press 2012 Notices This is the first version of the first edition of this chapter. It was updated March 21, 2012. Check elangdell.cali.org for the latest edition/version and revision history. This work by Colin Miller is licensed and published by CALI eLangdell Press under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. CALI and CALI eLangdell Press reserve under copyright all rights not expressly granted by this Creative Commons license. CALI and CALI eLangdell Press do not assert copyright in US Government works or other public domain material included herein. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available through [email protected]. In brief, the terms of that license are that you may copy, distribute, and display this work, or make derivative works, so long as you give CALI eLangdell Press and the author credit; you do not use this work for commercial purposes; and you distribute any works derived from this one under the same licensing terms as this. Suggested attribution format for original work: Colin Miller, Evidence: Best Evidence Rule, Published by CALI eLangdell Press. Available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 3.0 License. CALI® and eLangdell® are United States federally registered trademarks owned by the Center for Computer-Assisted Legal Instruction. The cover art design is a copyrighted work of CALI, all rights reserved. The CALI graphical logo is a trademark and may not be used without permission. Should you create derivative works based on the text of this book or other Creative Commons materials therein, you may not use this book’s cover art and the aforementioned logos, or any derivative thereof, to imply endorsement or otherwise without written permission from CALI. -

An Introduction to the Rules of Evidence Applicable to Collection Cases in Maryland Trial Courts Lynn Mclain University of Baltimore, [email protected]

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 7-30-2002 An Introduction To The Rules Of Evidence Applicable To Collection Cases In Maryland Trial Courts Lynn McLain University of Baltimore, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Evidence Commons, and the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Lynn McLain, An Introduction To The Rules Of Evidence Applicable To Collection Cases In Maryland Trial Courts, (2002). Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac/916 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN INTRODUCTION TO THE RULES OF EVIDENCE ApPLICABLE TO COLLECTION CASES IN MARYLAND TRIAL COURTS Prof. Lynn McLain University of Baltimore School of Law July 30, 2002 ~ PROFESSOR LYNN McLAIN ~ University of Baltimore School of Law John and Frances Angelos Law Center 1420 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21201-5779 Professor McLain (J.D., 1974, with distinction, Duke University School of Law), was an associate at Piper & Marbury, a graduate fellow at Duke, and then in 1977 joined the faculty at the University of Baltimore School of Law, where she is the Dean Joseph Curtis Faculty Fellow and teaches courses in evidence and copyright law. Prof. McLain is admitted to the bars of the Maryland Court of Appeals (December 1974), the United States District Court for the District of Maryland (March 1975), and the United States Supreme Court (March 1990). -

New York Evidentiary Foundations Randolph N

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Books 1993 New York Evidentiary Foundations Randolph N. Jonakait H. Baer E. S. Jones E. Imwinkelried Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_books Part of the Evidence Commons Recommended Citation Jonakait, Randolph N.; Baer, H.; Jones, E. S.; and Imwinkelried, E., "New York Evidentiary Foundations" (1993). Books. Book 4. http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_books/4 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. New York .Evidentiary Foundations RANDOLPH N. JONAKAIT HAROLD BAER, JR. E. STEWART JONES, JR. EDWARD J. IMWINKELRIED THE MICHIE COMPANY Law Publishers CHARLOTIESVILLE, Vlli:GINIA CoPYRIGHT ~ 1H93 BY THE MICHIE COMI'ANY Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 93-77731 ISBN: 1-55834-058-0 All rights reserved. lllllllllllllllllllllllllm IIIII SUMMARY TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Table of Contents . v Chapter 1. Introduction . 1 Chapter 2. Related Procedures .. .. .. .. ... ... .. .. .. .. .. .. ..... 11 Chapter 3. The Competency ofWitnesses .......................... 25 Chapter 4. Authentication . 45 Chapter 5. Limitations on Credibility Evidence . 99 Chapter 6. Limitations on Evidence That Is Relevant to the Merits of the Case . 129 Chapter 7. Privileges and Similar Doctrines . 155 Chapter 8. The Best Evidence Rule . 199 Chapter 9. Opinion Evidence ......................................... 225 Chapter 10. The Hearsay Rule, Its Exemptions, and Its Excep- tions ......................................................... 241 Chapter 11. Substitutes for Evidence . .. .. .. .... .. .. .. .. ..... ... .. 315 Index ......................................................................... 329 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Summary Table of Contents 111 Chapter 1. Introduction .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 · A. Introduction . 1 B. Laying a Foundation - In General . 2 1.