Appendix a ARTICLE IX—AUTHENTICATION Sec. 9-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

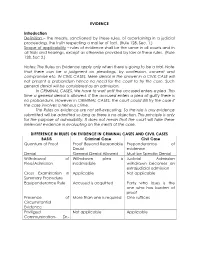

EVIDENCE Introduction Definition – the Means, Sanctioned by These

EVIDENCE Introduction Definition – the means, sanctioned by these rules, of ascertaining in a judicial proceeding, the truth respecting a matter of fact. (Rule 128, Sec. 1.) Scope of applicability – rules of evidence shall be the same in all courts and in all trials and hearings, except as otherwise provided by law or these rules. (Rule 128, Sec 2.) Notes: The Rules on Evidence apply only when there is going to be a trial. Note that there can be a judgment on pleadings, by confession, consent and compromise etc. IN CIVIL CASES. Mere denial in the answer in a CIVIL CASE will not present a probandum hence no need for the court to try the case. Such general denial will be considered as an admission. In CRIMINAL CASES, We have to wait until the accused enters a plea. This time a general denial is allowed. If the accused enters a plea of guilty there is no probandum. However in CRIMINAL CASES, the court could still try the case if the case involves a heinous crime. The Rules on evidence are not self-executing. So the rule is any evidence submitted will be admitted so long as there is no objection. This principle is only for the purpose of admissibility. It does not mean that the court will take these irrelevant evidence in evaluating on the merits of the case. DIFFERENCE IN RULES ON EVIDENCE IN CRIMINAL CASES AND CIVIL CASES BASIS Criminal Case Civil Case Quantum of Proof Proof Beyond Reasonable Preponderance of Doubt evidence Denial General Denial Allowed Must be Specific Denial Withdrawal of Withdrawn plea is Judicial Admission Plea/Admission -

10.9 the Right to Cross-Examination

Minnesota Administrative Procedure Chapter 10. Evidence Latest Revision: 2014 10.9 THE RIGHT TO CROSS-EXAMINATION The APA guarantees all parties to a contested case the opportunity to cross- examine: “Every party or agency shall have the right of cross-examination of witnesses who testify, and shall have the right to submit rebuttal evidence.”1 The OAH rules affirm this right2 and extend it to include the right to call an adverse party for cross-examination as part of a party's case in chief.3 In the case of multiple parties, the sequence of cross-examination is determined by the ALJ.4 While application of the right to cross-examine is a simple matter in the case of witnesses who testify, does the existence of this right prevent the use of evidence from witnesses who do not give oral testimony? In short, is it ever proper to receive written evidence5 in contested cases, sworn or unsworn, offered by a party who fails to call the author of the written evidence. In Richardson v. Perales, the United States Supreme Court held that where the written evidence consisted of unsworn statements of medical experts, receipt of the evidence was proper.6 Perales involved a claim for social security disability benefits based on a back injury. At the hearing, Perales offered the oral testimony of a general practitioner who had examined him. The government countered with written medical reports, containing observations and conclusions of four specialists who had examined Perales in connection with his claim at various times.7 The reports were received over several objections by Perales's counsel, including hearsay and lack of an opportunity to cross-examine. -

An Introduction to the Rules of Evidence Applicable to Collection Cases in Maryland Trial Courts Lynn Mclain University of Baltimore, [email protected]

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 7-30-2002 An Introduction To The Rules Of Evidence Applicable To Collection Cases In Maryland Trial Courts Lynn McLain University of Baltimore, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Evidence Commons, and the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Lynn McLain, An Introduction To The Rules Of Evidence Applicable To Collection Cases In Maryland Trial Courts, (2002). Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac/916 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN INTRODUCTION TO THE RULES OF EVIDENCE ApPLICABLE TO COLLECTION CASES IN MARYLAND TRIAL COURTS Prof. Lynn McLain University of Baltimore School of Law July 30, 2002 ~ PROFESSOR LYNN McLAIN ~ University of Baltimore School of Law John and Frances Angelos Law Center 1420 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21201-5779 Professor McLain (J.D., 1974, with distinction, Duke University School of Law), was an associate at Piper & Marbury, a graduate fellow at Duke, and then in 1977 joined the faculty at the University of Baltimore School of Law, where she is the Dean Joseph Curtis Faculty Fellow and teaches courses in evidence and copyright law. Prof. McLain is admitted to the bars of the Maryland Court of Appeals (December 1974), the United States District Court for the District of Maryland (March 1975), and the United States Supreme Court (March 1990). -

"Ancient Documents" As Evidence

The Archivist and "Ancient Documents" as Evidence Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/26/4/487/2744520/aarc_26_4_148255750366p7l6.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 By CYRUS B. KING* D. H. Hill Library N. C. State of the University of North Carolina at Raleigh GENERATION or more after the occurrence of a certain event, when all of the witnesses have passed from the scene, A litigation stemming from that event normally must proceed on the basis of documents created contemporaneously with the event. As the custodian of needed documents, an archivist may very well find himself embroiled in litigation that requires the use of evidentiary documents in his care. The archivist's involve- ment ordinarily results from the question of custody, one of the several conditions affecting the admissibility of a document as evidence in a court of law under the common-law ancient documents rule. For some three centuries judges have accepted the validity of the common-law rule that an ancient document, under certain con- ditions, may be taken as sufficiently genuine to be submitted to a jury as evidence without further authentication of its genuineness.1 The reason for such a rule, of course, is the impossibility of ob- taining living testimony to prove that the document is indeed gen- uine. Until a certain lapse of time, after which all of the living witnesses are gone, there is no necessity for the application of the rule. From such necessity evolved the common-law ancient documents rule. At first the requirement -

The Changing Face of the Rule Against Hearsay in English Law

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Review Akron Law Journals July 2015 The hC anging Face of the Rule Against Hearsay in English Law R. A. Clark Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the Evidence Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Clark, R. A. (1988) "The hC anging Face of the Rule Against Hearsay in English Law," Akron Law Review: Vol. 21 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol21/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Clark: English Rule Against Hearsay THE CHANGING FACE OF THE RULE AGAINST HEARSAY IN ENGLISH LAW by R.A. CLARK* The rule against hearsay has always been surrounded by an aura of mystery and has been treated with excessive reverence by many English judges. Traditionally the English courts have been reluctant to allow any development in the exceptions to this exclusionary rule, regarding hearsay evidence as being so dangerous that even where it appears to be of a high pro- bative calibre it should be excluded at all costs. -

Ohio Rules of Evidence

OHIO RULES OF EVIDENCE Article I GENERAL PROVISIONS Rule 101 Scope of rules: applicability; privileges; exceptions 102 Purpose and construction; supplementary principles 103 Rulings on evidence 104 Preliminary questions 105 Limited admissibility 106 Remainder of or related writings or recorded statements Article II JUDICIAL NOTICE 201 Judicial notice of adjudicative facts Article III PRESUMPTIONS 301 Presumptions in general in civil actions and proceedings 302 [Reserved] Article IV RELEVANCY AND ITS LIMITS 401 Definition of “relevant evidence” 402 Relevant evidence generally admissible; irrelevant evidence inadmissible 403 Exclusion of relevant evidence on grounds of prejudice, confusion, or undue delay 404 Character evidence not admissible to prove conduct; exceptions; other crimes 405 Methods of proving character 406 Habit; routine practice 407 Subsequent remedial measures 408 Compromise and offers to compromise 409 Payment of medical and similar expenses 410 Inadmissibility of pleas, offers of pleas, and related statements 411 Liability insurance Article V PRIVILEGES 501 General rule Article VI WITNESS 601 General rule of competency 602 Lack of personal knowledge 603 Oath or affirmation Rule 604 Interpreters 605 Competency of judge as witness 606 Competency of juror as witness 607 Impeachment 608 Evidence of character and conduct of witness 609 Impeachment by evidence of conviction of crime 610 Religious beliefs or opinions 611 Mode and order of interrogation and presentation 612 Writing used to refresh memory 613 Impeachment by self-contradiction -

Evidence: Admissibility of Newspapers Under the Hearsay Rule

EVIDENCE: ADMISSIBILITY OF NEWSPAPERS UNDER THE HEARSAY RULE NEWSPAPERS OFFERED in evidence as proof of the facts recited therein are out-of-court declarations generally held to be inadmissible under the hearsay rule.' However, in a recent decision, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held that an exception to this exclusionary rule will be made where the evidence in question is necessary and the circumstances under which the declaration was made provide guarantees of trust- worthiness. In Dallas County v. Commercial Union Assur. Co.,2 a county in Alabama, following the collapse of its courthouse on July 7, 1957, sought to recover on a lightning insurance policy, contending that the collapse was caused by lightning which had struck the courthouse on July 2. The plaintiff attributed char in the debris to lightning. Deny- ing liability, the defendant caimed that lightning had not struck the courthouse and that the collapse was caused by structural weaknesses.8 To explain the presence of char, the defendant introduced expert testi- mony indicating a fire at some earlier date and offered in evidence a June 9, 19O1, copy of the local newspaper, which contained an anony- mous article reporting a fire in the then unfinished tower.4 The federal district judge admitted the document as "part of the records"5 of the newspaper company over the plaintiff's objection that this was hearsay evidence. On appeal from judgment on a jury verdict for the defendant, the plaintiff assigned as error the admission of the newspaper into evidence. 'Watford v. Evening Star Newspaper Co., zxi F.zd 31 (D.C. -

2016-05-07 Evidence Rules Report to the Standing Committee

COMMITTEE ON RULES OF PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE OF THE JUDICIAL CONFERENCE OF THE UNITED STATES WASHINGTON, D.C. 20544 JEFFREY S. SUTTON CHAIRS OF ADVISORY COMMITTEES CHAIR STEVEN M. COLLOTON REBECCA A. WOMELDORF APPELLATE RULES SECRETARY SANDRA SEGAL IKUTA BANKRUPTCY RULES JOHN D. BATES CIVIL RULES DONALD W. MOLLOY CRIMINAL RULES WILLIAM K. SESSIONS III EVIDENCE RULES MEMORANDUM TO: Hon. Jeffrey S. Sutton, Chair Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure FROM: Hon. William K. Sessions, III, Chair Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules RE: Report of the Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules DATE: May 7, 2016 ______________________________________________________________________________ I. Introduction The Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules (the “Committee”) met on April 29, 2016 in Alexandria, Virginia. The Committee seeks final approval of two proposed amendments for submission to the Judicial Conference: 1. Amendment to Rule 803(16), the ancient documents exception to the hearsay rule, to limit its application to documents prepared before 1998; and 2. Amendment to Rule 902 to add two subdivisions that would allow authentication of certain electronic evidence by way of certification by a qualified person. The Committee also seeks approval of a Manual on best practices for authenticating electronic evidence, to be published by the Federal Judicial Center. June 6-7, 2016 Page 45 of 772 Report to the Standing Committee Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules May 7, 2016 Page 2 II. Action Items A. Amendment Limiting the Coverage of Rule 803(16) Rule 803(16) provides a hearsay exception for “ancient documents.” If a document is more than 20 years old and appears authentic, it is admissible for the truth of its contents. -

American Journal of Trial Advocacy Authentication of Social Media Evidence.Pdf

Authentication of Social Media Evidence Honorable Paul W. Grimm† Lisa Yurwit Bergstrom†† Melissa M. O’Toole-Loureiro††† Abstract The authentication of social media evidence has become a prevalent issue in litigation today, creating much confusion and disarray for attorneys and judges. By exploring the current inconsistencies among courts’ de- cisions, this Article demonstrates the importance of the interplay between Federal Rules of Evidence 901, 104(a), 104(b), and 401—all essential rules for determining the admissibility and authentication of social media evidence. Most importantly, this Article concludes by offering valuable and practical suggestions for attorneys to authenticate social media evidence successfully. Introduction Ramon Stoppelenburg traveled around the world for nearly two years, visiting eighteen countries in which he “personally met some 10,000 people on the road, slept in 500 different beds, ate some 1,500 meals[,] and had some 600 showers,” without spending any money.1 Instead, his blog, Let-Me-Stay-For-A-Day.com, fueled his travels.2 He spent time each evening updating the blog, encouraging people to invite him to stay † B.A. (1973), University of California; J.D. (1976), University of New Mexico School of Law. Paul W. Grimm is a District Judge serving on the United States District Court for the District of Maryland. In September 2009, the Chief Justice of the United States appointed Judge Grimm to serve as a member of the Advisory Committee for the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Judge Grimm also chairs the Advisory Committee’s Discovery Subcommittee. †† B.A. (1998), Amherst College; J.D. (2008), University of Baltimore School of Law. -

Evidence (Real & Demonstrative)

Evidence (Real & Demonstrative) E. Tyron Brown Hawkins Parnell Thackston & Young LLP Atlanta, Georgia 30308 I. TYPES OF EVIDENCE There are four types of evidence in a legal action: A. Testimonial; B. Documentary; C. Real, and; D. Demonstrative. A. TESTIMONIAL EVIDENCE Testimonial evidence, which is the most common type of evidence,. is when a witness is called to the witness stand at trial and, under oath, speaks to a jury about what the witness knows about the facts in the case. The witness' testimony occurs through direct examination, meaning the party that calls that witness to the stand asks that person questions, and through cross-examination which is when the opposing side has the chance to cross-examine the witness possibly to bring-out problems and/or conflicts in the testimony the witness gave on direct examination. Another type of testimonial evidence is expert witness testimony. An expert witness is a witness who has special knowledge in a particular area and testifies about the expert's conclusions on a topic. ln order to testify at trial, proposed witnesses must be "competent" meaning: 1. They must be under oath or any similar substitute; 2. They must be knowledgeable about what they are going to testify. This means they must have perceived something with their senses that applies to the case in question; 3. They must have a recollection of what they perceived; and 4. They must be in a position to relate what they communicated 1 Testimonial evidence is one of the only forms of proof that does not need reinforcing evidence for it to be admissible in court. -

Download Barkai's Hawaii Rules of Evidence

HAWAII RULES OF EVIDENCE HANDBOOK 2018 Professor John Barkai William S. Richardson School of Law University of Hawaii The Hawaii Rules of Evidence were last amended in 2011 i HAWAII RULES OF EVIDENCE HANDBOOK 2018 Professor John Barkai William S. Richardson School of Law University of Hawaii Honolulu, HI 96822 ISBN: 978-1-948027-00-7 Regarding copyright - there is none. Of course, there is no claim to copyright the Hawaii Rules of Evidence, which are government works. In addition, your may freely copy and use other sections of this handbook, primarily the appendices, under a Creative Commons Attribution (CCBY) 4.0 License, which essentially means that you may use, share, or adapt the information in the appendices for any purpose, even commercial, if you give "appropriate credit" and indicate changes you made, if any. You cannot restrict others from using these materials. The suggested attribution is to cite the material as: John Barkai, Hawaii Rules of Evidence Handbook (2018). No legal advice. The author and publisher are offering no legal advice. The law is whatever the judge in your case says the law is. Formatting. There seems to be no standard formatting style for presenting the Hawaii Rules of Evidence or the Federal Rules of Evidence. This handbook uses formatting generally consistent with the formatting used for these rules in Hawaii Revised Statutes, but with some paragraph modifications intended to make the understanding and application of the rules as clear as possible - but clarity and understanding of the rules of evidence by using the text alone is almost impossible. -

Manual on Best Practices for Authenticating Digital Evidence

BEST PRACTICES FOR AUTHENTICATING DIGITAL EVIDENCE HON. PAUL W. GRIMM United States District Judge for the District of Maryland former member of the Judicial Conference Advisory Committee on Civil Rules GREGORY P. JOSEPH, ESQ. Partner, Joseph Hage Aaronson, New York City former member of the Judicial Conference Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules DANIEL J. CAPRA Reed Professor of Law, Fordham Law School Reporter to the Judicial Conference Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules The publisher is not engaged in rendering legal or other professional advice, and this publication is not a substitute for the advice of an attorney. If you require legal or other expert advice, you should seek the services of a competent attorney or other professional. © 2016 LEG, Inc. d/b/a West Academic 444 Cedar Street, Suite 700 St. Paul, MN 55101 1-877-888-1330 Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-68328-471-0 [No claim of copyright is made for official U.S. government statutes, rules or regulations.] TABLE OF CONTENTS Best Practices for Authenticating Digital Evidence ..................... 1 I. Introduction ........................................................................................ 1 II. An Introduction to the Principles of Authentication for Electronic Evidence: The Relationship Between Rule 104(a) and 104(b) ........ 2 III. Relevant Factors for Authenticating Digital Evidence ................... 6 A. Emails ......................................................................................... 7 B. Text Messages .........................................................................